of incentives, lack of training, no motivation. Conclusions. The research activity of our doctors is similar to that found in other studies. Attitude to research is no better than "acceptable." The main hindrances stated were: case-load and lack of time.

Introduction

Research in primary care is seen as one of the basic functions of primary care teams1 along with their clinical and teaching activities. While necessary for the credibility and development of family medicine as a discipline,2 and to provide a scientific basis for health care,3-5 research also adds quality, effectiveness, and efficiency to clinical practice.

Thus research is of interest to patients (as it improves the quality of care, decreases variability in clinical practice and reinforces the principle of equity in health care), to health care professionals (as it improves their training, consolidates their professional activity, and increases motivation and professional satisfaction), and to managers and planners.3,5

A number of reasons support the benefits of carrying out research within the primary care setting. One noteworthy factor is the availability of data on the population for which the results of research are to be applied. Because patients are followed in primary care throughout their lifetime, the most prevalent diseases can be detected in earlier stages--which increases our knowledge of the natural history of these entities. Access to an entire population means that causal agents and risk practices for certain diseases can be studied, along with the influence on health status of psychosocial and familial factors.4-8

In Spain, research in primary care settings lacks the benefits of long-standing tradition or a significant body of research experience.9 However, recent years have seen signs of change and sustained growth.10 During the period from 1990 to 1997, the number of research articles on primary care topics (identified on the basis of the first author's affiliation with a primary care center), according to MEDLINE, rose from 88 to 154 documents.11 Even so, a bibliometric analysis by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria for the period 1994-2000 showed primary care to be all but nonexistent: only 0.4% of all citable items under "health centers" were from primary care centers.12 Moreover, research in primary care is still rarely mentioned in research projects sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry.13 Spain is not the only country in this situation, also seen in other European countries.14-16

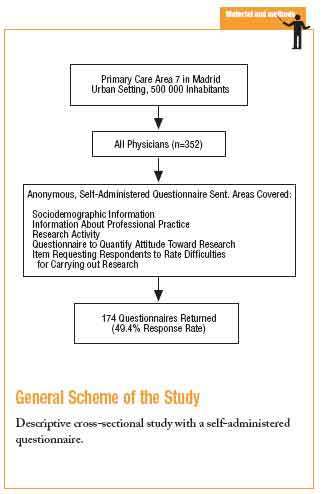

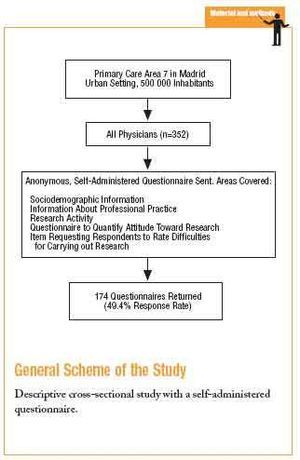

In order to devise strategies to foment research, it is first appropriate to determine the current state of research activity in the primary care setting, physicians' attitudes toward research, and factors that facilitate or impede research.2 The aims of our study were to a) obtain quantitative information on research activity among physicians who work in Primary Care Area 7 (Madrid, central Spain) during the last 5 years and analyze associated factors; b) describe attitudes toward research among our physicians; and c) evaluate the obstacles encountered to carrying out research.

Material and Methods

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study in which the population consisted of all primary care physicians in Health Care Area 7 in Madrid, Spain. This entirely urban area serves a population of approximately 500 000 inhabitants. The period of study was June and July, 2003.

Information was collected with an anonymous, self-administered questionnaire that was sent by internal e-mail to each physician on two occasions 15 days apart to increase uptake. A covering letter explained the objectives of the study and the procedure for returning the completed questionnaire to the Training and Research Unit.

The questionnaire (see supplementary material in internet) contained items covering sociodemographic variables (age and sex), information about professional practice, training in research methods, and research activity. To obtain information about physicians' attitude toward research we included items from a previously validated questionnaire,2 i.e., 20 closed items, 18 to be scored from 0 to 4 on a 5-point Likert-like scale and 2 dichotomous items scored 0 or 4. Overall score for each questionnaire was calculated as the sum of the scores on each item. Total scores ranged from 0 to 80 points; the higher the score, the better the physician´s attitude toward research.

An item was added that inquired about six obstacles to research identified in other studies.5,6,8,16-19 Participants were asked to assign to each factor a score from 1 (least difficulty) to 5 (greatest difficulty).

The data were processed and analyzed with the SPSS (v. 10). Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for quantitative variables, and absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for qualitative variables. For bivariate analyses the chi-squared test was used to compare proportions, and Student's t test and analysis of variance were used to compare mean values. For multivariate analysis we used forward stepwise logistic regression with publication of at least one research article in the last 5 years as the dependent variable. Variables found to be statistically significant in the bivariate analysis were added successively to the model.

Results

Of 352 questionnaires that were e-mailed, a total of 174 were received (49.4% response rate). Mean age of the respondents was 43.2 (7.3) years, and two thirds (65.9%) were women. Slightly more than half (55.5%) were specialists in family and community medicine (FCM), and of this proportion, 79.1% had completed a residency program in FCM. Mean number of years in practice was 15.4 (7.9), and 18.3% of the respondents held a PhD. Most (84.7%) worked as members of a primary care team, 12.4% were employed at centers administered under a "traditional" management model (i.e., the recent reforms in primary health care administration had not yet been implemented at their center), and 2.9% were in practice at primary care emergency services. About one third (36.2%) of the physicians we surveyed belonged to health centers that carried out training activities, and 21.4% were tutors of residents. Patient load was 31 to 40 per day for 45.8%, from 41 to 50 for 29.2%, and more than 50 for 12.5% of the respondents. Nearly two thirds (64.9%) had completed at least one course in research methodology.

The results for research activity by participants showed that 86 (49.4%) had published at least one article during the preceding 5 years. Table 1 shows how publications were distributed according to type of publication.

More than one third (38%) had given presentations at congresses, and 29.2% has taken part in clinical trials. Nearly two thirds (63.2%) had been or were involved in a research project, although only 24.9% were so involved at the time of the study.

The bivariate analysis detected statistically significant differences for having published at least one research article, male sex, specialization in FCM, holding a doctorate, having been in practice for 15 years or more, working at a health center where training activities were performed, being a tutor for residents, and having completed a course in research methodology (Table 2). The multivariate analysis showed the variables associated with having published at least one research article to be specialization in FCM (OR, 4.1; 95% CI, 1.8-11.4), holding a doctorate (OR, 7.0; 95% CI, 1.5-32.7) and having completed a course in research methodology (OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.1-9.4).

Attitude toward research was evaluated in the 156 questionnaires that had been fully completed. Mean score was 53.5, with a standard deviation of 10.6 and a range of 10 to 76. Table 3 shows the mean scores for each variable.

Difficulties for performing research that were scored highest were, in decreasing order, patient load, structural deficiencies, lack of multicenter research projects, lack of incentives, lack of training, and lack of motivation (Table 4).

Discussion

Although the percentage response rate was low, it was similar to that reported in other published studies based on the same methods.8,15,16 When we compared respondents to the entire study population for the variables sex, age, and whether they worked at a "traditional" health center or as part of a primary health care team, we found that responders were younger and that a larger percentage worked in primary care teams. This difference, together with earlier findings of higher response rates among professionals with a publication record,8,13,15 might have lead to overestimation of research activity and attitude toward research on the part of the professionals studied here. One of the limitations of our study was that we relied on self-reported information regarding publications, as did other studies.15,16,18,20 This might have affected how publications were quantified, although it would have had less of an effect on other factors associated with having a publication record.

About half of the participants (49.4%) had published at least one research article in the last 5 years. Similar percentages were reported in earlier studies,15,18 although in some cases the figures ranged from 4% to 11%.16,20,21 In comparison to an earlier study17, fewer participants reported having given congress presentations. At the time of the study only one fourth of the participants (24.9%) were involved in research, and although this value is low, it is higher than the figure given in other studies.14,20

Factors associated with having a publication record in the last 5 years were specialization in FCM, having completed work toward a PhD, and having completed a course in research methods. These factors are similar to the ones noted in earlier studies.8,15 We note, however, that some studies also found working at a teaching center was a factor associated with publishing.8,16 In the present study this variable was found to be associated with publication in the bivariate analysis but not in the multivariate analysis. This may reflect the fact that working at a teaching center is related with specialization, holding a doctorate, or having completed a course in research methodology, all of which are also associated with publication.

The mean overall score for attitude toward research, 53.5 (10.6), was similar to the figure reported in the only other study that used the same questionnaire2 (52.0 [9.1]). That study surveyed only physicians who were working at teaching centers. In comparison to the figure we obtained when we considered only physicians in the present study who were working at teaching centers (56.5; SD, 9.6), the difference was somewhat greater. Given that the range of scores attainable in the questionnaire was from 0 to 80, the overall score in the present study seems acceptable.

When we examined the difficulties encountered to research activity, the highest scores (greatest difficulty) were for patient load and lack of time, followed by structural deficiencies and lack of multicenter research projects. The lack of time and patient load are problems that have been identified previously.8,15-17 However, of the studies that emphasized these factors, we found that the main obstacles were lack of money to finance research17 and lack of support staff for data collection.16

This study found that research activity among the physicians we surveyed was similar to or more extensive than in other settings, and that the overall attitude toward research was acceptable. The difficulties identified here will help us to establish areas of improvement in planning research in our health care area. It would be advisable to complement this research with other studies based on qualitative methods to obtain more detailed information on practitioners´ opinions regarding research.