To determine the patterns of antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli strains isolated from adult patients with urinary tract infection (UTI), and to stratify the results by age and type of UTI to verify if there are statistically significant differences that can help physicians to prescribe better empirical antibiotherapy.

DesignCross-sectional prospective study.

LocationCommunity of Getafe (Madrid). Primary care level.

Participants100 E. coli strains, randomly chosen, isolated from the urine (104–105cfu/ml) of different patients from primary care centers in the Getafe area.

Main measurementsThe antibiotic susceptibility of the strains was evaluated and the results were stratified by age and type of UTI. The clinical and demographic data of the patients were analyzed, classifying each episode as complicated UTI or uncomplicated UTI.

ResultsStrains isolated from patients with uncomplicated UTI showed significantly greater susceptibility than those of complicated UTI to amoxicillin (65.9% vs. 30.6%, p=0.001), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (95.5% vs. 77.6%, p=0.013) and ciprofloxacin (81.8% vs. 63.3%, p=0.047). In complicated UTI, susceptibility to ciprofloxacin was significantly greater in the ≤65 years age group compared to the older age group (78.3% vs. 50%, respectively, p=0.041). In the rest of antibiotics, no statistically significant differences were obtained when comparing by age (≤65 years versus >65 years), both in uncomplicated and complicated UTI.

ConclusionsClinical and demographic data of patients with UTI are of great importance in the results of the antibiotic susceptibility in E. coli. Antibiograms stratified by patient characteristics may better facilitate empirical antibiotic selection for UTI in primary care.

Determinar los patrones de sensibilidad antibiótica de cepas de Escherichia coli aisladas de pacientes adultos con infección del tracto urinario (ITU), y estratificar los resultados por edad y tipo de ITU para verificar si existen diferencias estadísticamente significativas que puedan ayudar a los médicos a la prescripción de una mejor antibioterapia empírica.

DiseñoEstudio transversal prospectivo.

EmplazamientoComunidad de Getafe (Madrid). Nivel de atención primaria.

Participantes100 cepas de E. coli, escogidas al azar, aisladas de orina (104 ->105ufc/ml) de diferentes pacientes de centros de atención primaria del área de Getafe.

Mediciones principalesSe evaluó la sensibilidad antibiótica de las cepas y los resultados se estratificaron por edad y tipo de ITU. Se analizaron los datos clínicos y demográficos de los pacientes de los que provenían, clasificándose cada episodio como ITU complicada o ITU no complicada.

ResultadosLas cepas aisladas de pacientes con ITU no complicada mostraron una sensibilidad antibiótica significativamente mayor que las de ITU complicada a amoxicilina (65,9% vs. 30,6%, p=0.001), amoxicilina/clavulánico (95,5% vs. 77,6%, p=0.013) y ciprofloxacino (81,8% vs. 63,3%, p=0.047). En la ITU complicada, la sensibilidad al ciprofloxacino fue significativamente mayor en el grupo de edad ≤65 años en comparación con el grupo de mayor edad (78,3% vs. 50%, p=0.041). Para el resto de antibióticos no se observaron diferencias significativas cuando se compararon por edad (≤65 versus>65), tanto en ITU no complicada como complicada.

ConclusionesLos datos clínicos y demográficos de los pacientes con ITU son de gran importancia en los resultados de la sensibilidad antibiótica en E. coli. Los antibiogramas estratificados por características de los pacientes podrían facilitar una mejor selección de antibioterapia empírica para las ITU en atención primaria.

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are common and contribute a significant burden to population health. In the United States, UTI account for approximately 10 million ambulatory visits and an estimated $2.000 in total cost each year.1 In Spain, one third of visits to primary care are due to infectious processes. Of these, 10% are urinary infections, most uncomplicated acute cistitis.2

UTI are one of the most common reasons for prescription of antimicrobials in primary care. Appropriate empirical therapy is important since treatment with an antimicrobial to which the uropathogen is resistant is associated with more clinical and microbiological failures, a longer median time to symptom resolution, higher re-consultation rates, and more subsequent antibiotics.3,4

Acute uncomplicated UTI in women is generally managed effectively and safely by empirical antibiotic therapy without a urine culture, laboratory testing is undertaken when empirical therapy fails. In recurrent UTI and in complicated UTI, urine cultures and antimicrobial susceptibility tests are recommended. For these reasons laboratory-based surveillance suffers from requesting bias, and probably overestimate resistance rates.

Antimicrobial resistance in common urinary pathogens is increasing at an alarming rate, as a result of overuse and misuse of antibiotics. Resistance patterns vary by geographic location, but are rising in Spain and globally.5,6

Knowledge of local susceptibility patterns is important for the selection of appropriate empirical therapy of UTI. Reporting updated local susceptibility patterns7 of the most frequently isolated microorganisms from urine samples influence physician decisions on therapeutic choices8 allowing to choose more appropriate and effective treatments.

Among outpatients, Escherichia coli is the main urinary tract pathogen, accounting for 60–85% of isolates. There are many studies in literature on the antibiotic susceptibility of E. coli and other uropathogens,5,9-12 but there are few studies, and less in primary care, evaluating the susceptibility of this microorganism considering some demographic and clinical data of patients such as sex, age and type of UTI.13-15 Our hypothesis is that if there were differences in the susceptibility patterns according to these characteristics of the patients, these last data would be more useful to guide clinicians to choose a more appropriate empirical treatment.

Our goal was to determine the antibiotic susceptibility patterns of E. coli strains isolated from adult patients with UTI attended at primary care centers in Getafe (Madrid, Spain), to compare them with the global laboratory susceptibility data of adults with positive urine cultures in primary care, and to stratify the results by age, and type of UTI, determined by clinical data, to verify if there are statistically significant variations.

Material and methodsDesign and study populationA cross-sectional prospective study was carried out. Inclusion criteria: Isolates of E. coli from urine (104–105cfu/ml) of adult patients, aged 18 and older, of all the primary care Centers in the Getafe area (Madrid, Spain); they were randomly selected from June 2016 to April 2017, one per patient; clinical and demographic data of the patients were obtained. Exclusion criteria: Isolates of E. coli from urine of patients aged less than 18 years, of hospital wards, and of the emergency department.

The study protocol (17/82) was approved by the Comité Ético de Investigación con Medicamentos of Hospital Universitario de Getafe.

Data and variablesClinical and demographic data (gender and age) were analyzed and, taking into account these features, the episodes were classified as complicated UTI, uncomplicated UTI or asymptomatic bacteriuria, according to the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) guidelines16; complicated UTI was considered in all men, and in patients with diabetes, indwelling catheter, neurogenic bladder, obstructive uropathy, history of pathologies or spinal surgeries, invasive urological procedure in the previous 3 months or immunosupresion.

The antibiotic susceptibility of the strains of E. coli was determined by broth microdilution (MicroScan panels, California, USA) to the following antibiotics: amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, fosfomycin, cotrimoxazole, nitrofurantoin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, cefotaxime, and imipenem. The results were interpreted according to the 2016 EUCAST guidelines17 except for amoxicillin/clavulanic in which the 2016 CLSI guidelines were used.18

Global laboratory susceptibility data of adults of primary care with significant isolation of E. coli from urine cultures were obtained from our laboratory computer system.

Statistical analysisFor the descriptive analysis, the absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies were used to express the qualitative variables. Following the confirmation of the parametric behavior, mean±standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range; IQR] were used to express the quantitative variables. To test the statistically significant differences scenarios either the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was performed for qualitative variables. Besides, either Student T test or U-Mann Whitney was used for quantitative variables according to the normality test. When the p-value was inferior to the alpha error (5%), a statistical significance was considered. The data analysis was performed with IBM SPSS statistics version 21.0 (IBM Corp; USA).

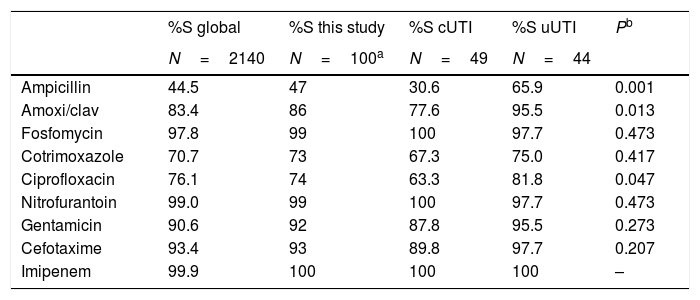

ResultsIn our health care area 30,144 urine cultures were processed in 2016, of which 19,533 (64.8%) came from adult patients of primary care. E. coli was isolated in 2140 (61.4% of the considered positive cultures); its antibiotic susceptibility is represented in Table 1.

Global antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli strains from urine cultures of adult outpatients in 2016, antibiotic susceptibility of the 100 isolates of the present study, and the same stratified by type of UTI, complicated versus uncomplicated.

| %S global | %S this study | %S cUTI | %S uUTI | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=2140 | N=100a | N=49 | N=44 | ||

| Ampicillin | 44.5 | 47 | 30.6 | 65.9 | 0.001 |

| Amoxi/clav | 83.4 | 86 | 77.6 | 95.5 | 0.013 |

| Fosfomycin | 97.8 | 99 | 100 | 97.7 | 0.473 |

| Cotrimoxazole | 70.7 | 73 | 67.3 | 75.0 | 0.417 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 76.1 | 74 | 63.3 | 81.8 | 0.047 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 99.0 | 99 | 100 | 97.7 | 0.473 |

| Gentamicin | 90.6 | 92 | 87.8 | 95.5 | 0.273 |

| Cefotaxime | 93.4 | 93 | 89.8 | 97.7 | 0.207 |

| Imipenem | 99.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | – |

S, susceptible; cUTI, complicated urinary tract infections; uUTI, uncomplicated urinary tract infections.

Of the 100 patients included, 15% were male and 85% female. The mean age was 58.3±18.8 years, 49 had complicated UTI, 44 uncomplicated UTI, and 7 had asymptomatic bacteriuria. Patients with uncomplicated UTI (44, all women) had a mean age of 54.1±18.0 years; Patients with complicated UTI (49 in total, 15 males and 34 females) had a mean age of 63.9±17.2 years, significantly higher (p=0.009).

The overall analysis of antibiotic susceptibility of the 100 E. coli strains was: amoxicillin (47%), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (86%), fosfomycin (99%), cotrimoxazole (73%), ciprofloxacin (74%), gentamicin (92%), nitrofurantoin (99%), cefotaxime (93%), and imipenem (100%) (Table 1). The antibiotic susceptibility of part of these strains stratified in those with complicated UTI (n=49) and those with uncomplicated UTI (n=44) as shown in Table 1.

When we compare the stratified antibiotic susceptibility, we found that strains isolated from patients with uncomplicated UTI showed significantly greater susceptibility than those of complicated UTI to amoxicillin (65.9% vs. 30.6%, p=0.001), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (95.5% vs. 77.6%, p=0.013) and ciprofloxacin (81.8% vs. 63.3%, p=0.047).

In complicated UTI, susceptibility to ciprofloxacin was significantly greater in the ≤65 years age group compared to the older age group (78.3% vs. 50%, respectively, p=0.041). In the rest of antibiotics, no statistically significant differences were obtained when comparing by age (≤65 years versus>65 years), both in uncomplicated and complicated UTI.

DiscussionAntimicrobial resistance in common urinary pathogens is increasing at an alarming rate. Because of the predominance of E. coli as causative agent, resistance to this species is often of epidemiologic resistance studies.11,12,19

Laboratory-based surveillance suffers from requesting bias since primary care physicians are advised against urine sampling in cases of uncomplicated UTI in non-pregnant women at least at first presentation. Urine culture is recommended for patients with complicated infection, and to guide a change of antimicrobials for women who do not respond to initial therapy. Since patients who fail initial empirical therapy for UTI have more risk factors for antimicrobial resistance, complications or recurrence and are more likely to be tested, laboratory-based surveillance is likely to overestimate resistance rates.20

Cumulative reports on antimicrobial susceptibility data provided by microbiological laboratories are important for selecting empiric treatments. There are many studies on antibiotic sensitivity of E. coli and other uropathogens.5,9-12 Weaknesses of these studies included a deficit of clinical data or even demographic data. A first or second episode of uncomplicated cystitis in a young woman is not the same as a UTI in a male with multiple episodes treated with antibiotics. Other methods of surveillance are required to provide unbiased estimates of antimicrobial resistance.

To identify individual patient or clinical characteristics that predict antimicrobial resistance, culture results should be linked to patient demographics and clinical characteristics; however, urine samples are often submitted to the laboratory with insufficient supplementary clinical information. One strength of our study is that we have reviewed medical records (n=100). In fact, we have more patients with complicated UTI (n=49) than with uncomplicated UTI (n=44) because in many uncomplicated UTI, the most common type of urinary infection in primary care, urine cultures are not send to the laboratory.

As expected, there were few differences in susceptibility between the global data of our laboratory (n=2140) and the data of the 100 strains included in this work (see Table 1), but there were differences in some antibiotics between strains from uncomplicated UTI and complicated UTI, and depending on the age in ciprofloxacin in patients with complicated UTI. In cefotaxime, there was not a statistically significant difference due, in our opinion, to the restricted sample size.

The data from the present study indicate that ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid non-susceptibility in E. coli are associated mostly with isolates from complicated UTI. Explanation could be previous antibiotic treatments that would have selected resistant strains that colonize patients and cause infections in the next weeks/months. In a recent study,15 an important variation in susceptibility to ciprofloxacin between cases of uncomplicated and complicated UTI were also observed.

Reviewing the medical records of this study, we ascertain that amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and ciprofloxacin are frequently used for the empirical treatment of complicated UTIs (data not shown), which would explain the selection of resistances to these antibiotics and the differences with the strains isolated from uncomplicated UTI. We suggest not using these antibiotics in the empirical treatment of complicated UTI since susceptibility to both is less than 80%.

It is important to note that the susceptibility to fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin remains high in all groups of patients analyzed. They would be an excellent option for the empirical treatment of cases of uncomplicated UTI, as it is stated in several guidelines.3,16 However, this is not the case of cotrimoxazole, 25% of strains are resistant. Although amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and ciprofloxacin are not considered appropriate empirical treatments for uncomplicated UTI, they would be an alternative as the rates of susceptibility are 95.5% and 81.8% respectively.

A limitation of our study is that it was performed in a single-center (population 218,945 inhabitants), but in our opinion they warn of the convenience of stratify susceptibility data to obtain more usefulness of them. The subset of patients in some groups was of inadequate size to show statistical significances. Another limitation is that E. coli data underestimate resistance rates because they exclude bacteria like, for example, Enterobacter cloace and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with intrinsic resistance to various antibiotics, although these species are rare in UTI in primary care.

In future it would be of interest to expand some group to obtain/to discard statistically differences in antibiotic susceptibility. Also, to evaluate the evolution over the time, as antibiotic resistance is dynamic.

We conclude that clinical and demographic data are of great importance in the results of antibiotic susceptibility in E. coli causing UTI and would be more useful than global data in the choice of empirical treatments. Antibiograms stratified by patient characteristics may better facilitate empirical antibiotic selection for UTI in primary care.

- •

E. coli is the pathogen most frequently involved in UTI. Global data of the antibiotic susceptibility (antibiograms) provided by laboratories influence the choice of empirical treatments.

- •

Most studies report global data of laboratories without stratification.

- •

Few studies evaluate the influence of clinical and demographic data on the results of antibiotic susceptibility.

- •

Clinical and demographic data are of great importance in the results of antibiotic susceptibility in E. coli causing UTI. Antibiograms stratified by patient characteristics may better facilitate empirical antibiotic selection for UTI in primary care.

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

None declared.