Las lesiones accidentales continúan siendo un importante problema de salud pública en todo el mundo. La población pediátrica está predispuesta a accidentes, y en este grupo las consecuencias son generalmente más graves. Las estadísticas internacionales y nacionales muestran que la pobreza y el nivel socio-económico bajo juegan un papel importante en la morbimortalidad por accidentes. Es evidente la heterogeneidad en las tasas de lesiones por edad, sexo y área geográfica. Se requieren más estudios científicos que analicen la epidemiología de las lesiones en la población pediátrica. Los resultados podrían ser de ayuda en el planteamiento de nuevas políticas de prevención de accidentes.

Accidental injuries remain to be an important public health problem worldwide. The pediatric population is predisposed to accidents and consequences are usually more severe. International and national statistics show that poverty and low socioeconomic level play an important role in morbidity and mortality due to accidents. Disparities in injury rates according to age, sex and geographical location are evident. Epidemiology of injury in the pediatric population needs more scientific study; these results may help to establish new policies on prevention and approach of accidents.

1. Introduction

Accidents are a major cause of morbidity and mortality at any age, and the pediatric population is no exception. Accidents do not respect age, sex, race, or socioeconomic status. Although it is a universal understanding that children have the right to live in a safe environment and to be protected against injury and violence, injuries in children remain to be a worldwide public health problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that ∼100 children die worldwide every hour due to accidental injuries, of which 90% are unintentional.1

The injuries, as a social phenomenon, have multiple consequences. They start with the suffering of the person and the interruption of the daily activities; later the need for ambulatory or hospital care is added with the respective economic expenditure. The situation can further progress, causing sequelae or death. In the case of the pediatric patient, interruption of activities includes absenteeism from school as well as absenteeism of parents from their work activities, with which the economic support to the family is interrupted. In a child, the sequelae are not limited to loss or dysfunction of an organ but also to the interruption of development with sequelae that can last a lifetime.

The term "external causes" refers to events or environmental circumstances that cause morbidity and mortality. It includes intentional situations such as violence and self-harm, and directly unintended effects referred to as accidents. The focus of this article is specifically about this last item, highlighting traumatic injuries.

The objective of this paper was to present an epidemiological overview of lesions in the pediatric patient without delving deeply into the specific types of injuries. The information provided is primarily focused on injury due to trauma.

2. Epidemiological transition and injuries

Scientific advances in medicine, health systems and improved life conditions of the population as well as disease prevention campaigns have modified the epidemiological pattern in almost the entire world. However, the speed with which this epidemiological transition has taken place in different regions of the world has been heterogeneous. Although some countries have achieved a great decrease in morbidity and mortality rates due to malnutrition and infectious diseases, in the poorest countries this group of diseases continues to exert a terrible impact on their populations.

Mexico is considered a country of intermediate economic resources and currently has a mixed pattern where the so-called "diseases of poverty" continue to be important, whereas chronic degenerative diseases progressively increase in proportion.

Injuries are rarely thought of as diseases of poverty, but it is interesting that they affect most in economically disadvantaged countries. According to a report of the WHO, unintentional injury rates are much higher in most countries in Africa and South Asia, whereas the European Union, Canada, U.S. and Australia have lower rates.1 Latin America, on the other hand, shows intermediate rates in the entire region. In terms of mortality, the heterogeneous distribution is similar worldwide. A recent study showed that in Mexico there are even regional differences in mortality due to injuries. Mortality is higher in the southern states of Mexico—where the lower socioeconomic status is greater— and lower in Mexico City.2

Undoubtedly, the culture of accident prevention that varies widely among populations plays an important role in the epidemiological differences. The causes of these differences are probably also due to a lower efficiency of the pre-hospital care systems and the emergency services in developing countries3 as well as insufficient prevention campaigns and poorly designed road and domestic infrastructure designed for accident prevention.

Interestingly, in the U.S., a greater risk of unintentional injuries has been demonstrated in African-Americans compared with Caucasian children. The factors that explain this are similar to what has been proposed for explaining regional differences.4

3. Predisposition of injuries in children

There are factors that favor that the child be a victim of accidental injuries. The child's immaturity makes him vulnerable to accidental injuries, given his lack of experience, and the recklessness of the age itself. In the case of the infant and pre-school child, their spirit of exploration makes them vulnerable. The daredevil spirit of the adolescent and the psychological need for social acceptance frequently propels this age group into risky behaviors. The negative influence that an adolescent has on another while driving a vehicle is clear, which increases the risk of an accident.5

Certain factors influence so that a similar situation affects a pediatric patient in a manner different from an adult. The greater weight of the head in proportion to the rest of the body makes it that, on the face of support at the level of the abdomen, the body be overtaken by the weight and, when balancing, will fall. In the case of road accidents by being run over, the child's smaller stature makes it difficult for them to be seen when they are getting close to a vehicle because the smaller the body of the individual, the less visible to a driver. In situations of disaster, the child is more vulnerable because he is less able to escape from the site of impact in a danger situation and has greater difficulty in following the instructions of those who seek to assist the victims.6 On the other hand, the pediatric patient reacts in a particular way to injuries due to their anatomic and physiological differences.

With respect to the mechanical vectors to which the child is exposed, the smaller size makes the child victim prone to more serious injuries because the mechanical forces are more greatly distributed throughout a smaller body. Also, the probability increases that various regions of the body are involved so that multiple trauma is more likely. A recent study on children victims of traffic accidents showed that the lower the age of the victim, the greater the risk of a disabling injury, brain injury, and thoracic trauma.7

Although there are controversies about the biomechanical mechanism explaining the differences between traumatic brain injury in children and adults,8 some considerations are evident. At the level of the skull, the bone structures are softer and thinner, providing less protection to the brain: areas such as the fontanels and sutures really offer little resistance upon impact.9

The brain itself is less resistant to being torn and more susceptible to displacement within the skull cavity. The child's brain is inflamed with greater ease as a consequence of a vascular reaction, which is characteristic of the pediatric patient.10

At the level of the spinal cord, the spinal column is hypermobile because the ligaments are more relaxed. This is particularly important at the cervical spine. The disk processes are arranged more horizontally, which facilitates anteroposterior displacements. The water content of the intervertebral discs is greater, which renders them more able to be deformed.11

At the level of the chest, the rib cage is less ossified so it is more tender and less protective of the internal structures.12 The effective rigidity is progressively attained during infancy.13 This facilitates contusion of the lungs, hemothorax and pneumothorax, which are more relatively frequent than in the adult.14

Abdominally, the pediatric patient has a less rigid and thinner wall than the adult patient, a reason why there is less protection of the internal organs. The smaller thickness of the adipose pannus decreases the ability of the abdominal wall to absorb the mechanical forces and buffer them.15 The larger proportional size of the liver and spleen during the first months of life that can partially extend beyond the edges of the rib cage can cause that these organs not be protected by the skeleton, as occurs at older ages. Even for the retrocostal structures, the rib cage is incompletely ossified in the first years, which results in a less protective material.9

At the level of the extremities, the bones are smaller in all their dimensions and are comprised of less dense and less resistant material to external mechanical forces.16,17 A smaller volume and strength of the muscles also confer less protection. The injuries such as "greenstick" fracture and injuries of the growth disk are exclusive to the pediatric patient according to their histological and anatomic peculiar characteristics.

4. Morbidity

Each year, ∼10 million children worldwide require hospita lization as a result of unintentional injuries. Of these children, 95% of these injuries occur in countries of intermediate or low income.1 In a recent study, without differentiating by age groups, it was reported that morbidity from injuries on the American continent frankly surpasses other topics such as infectious, cardiovascular and malignant diseases.18

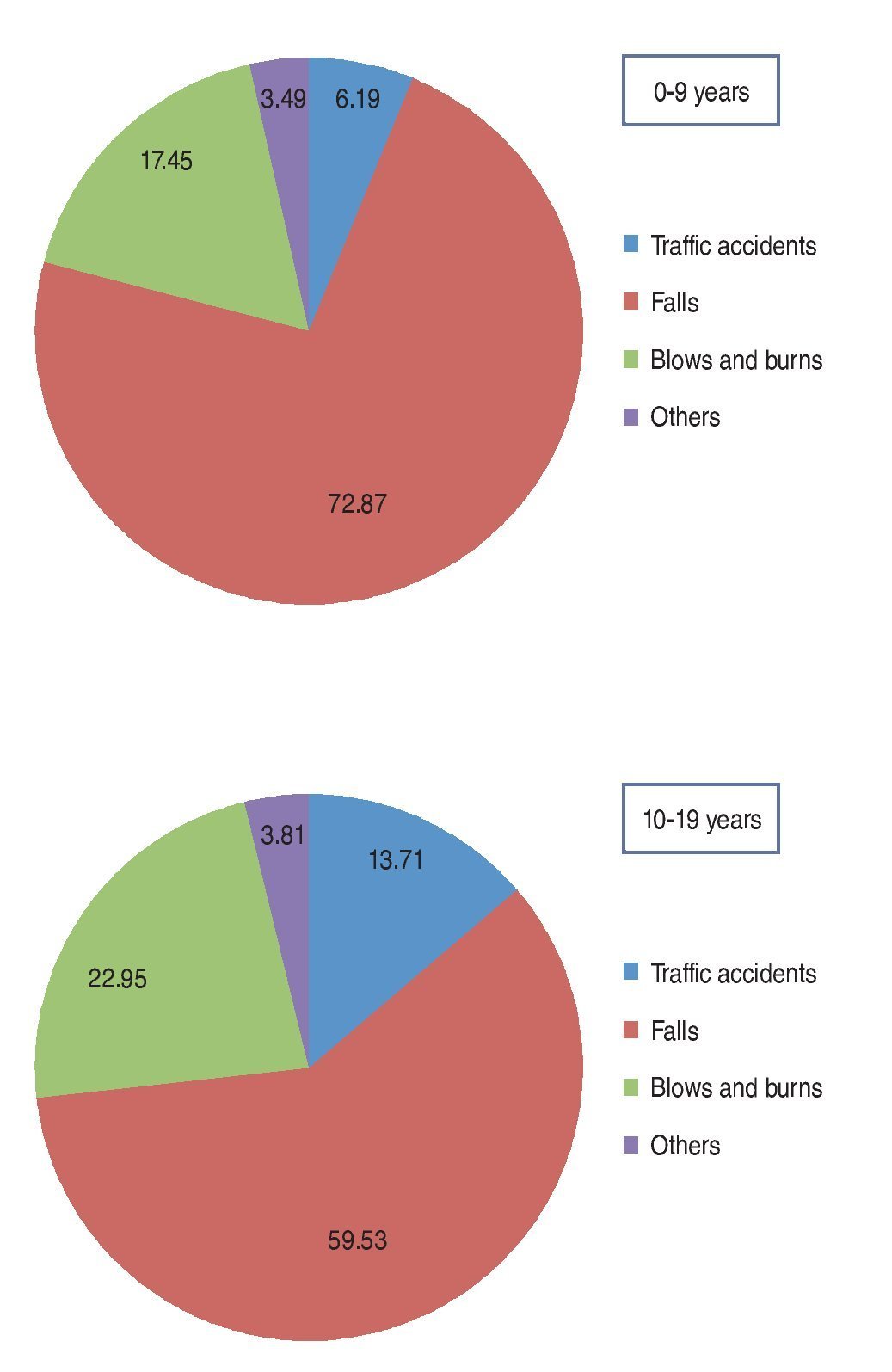

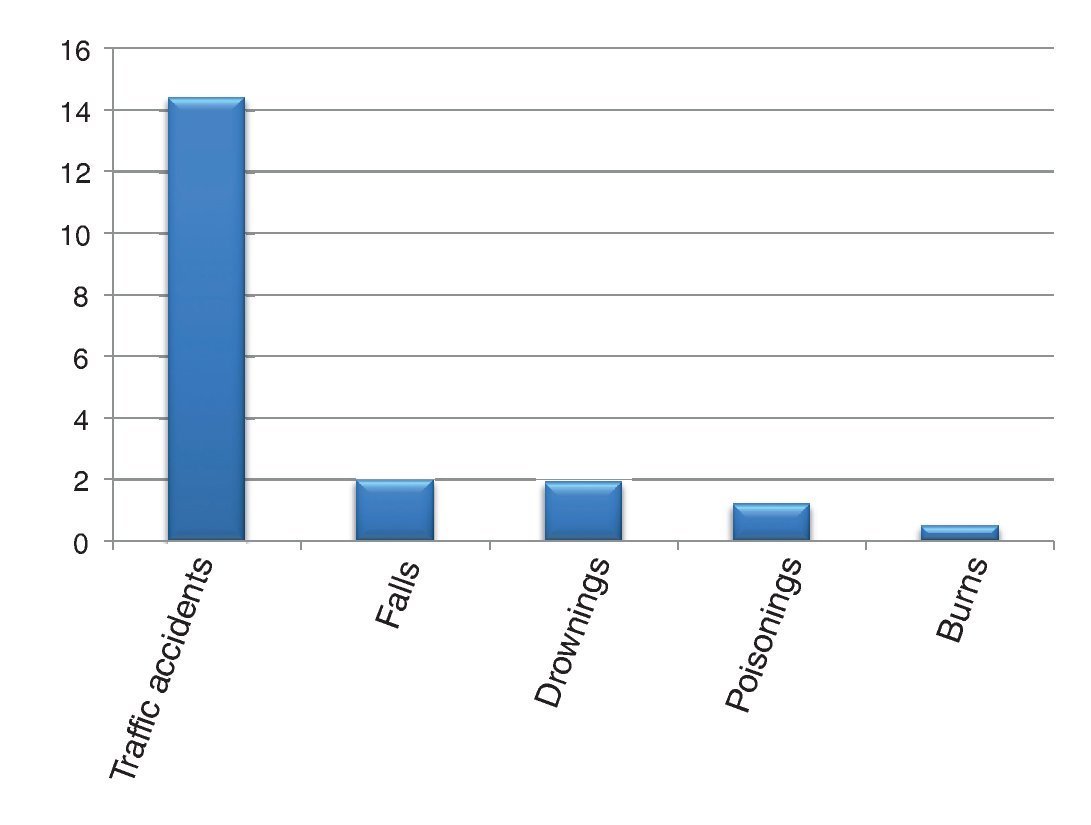

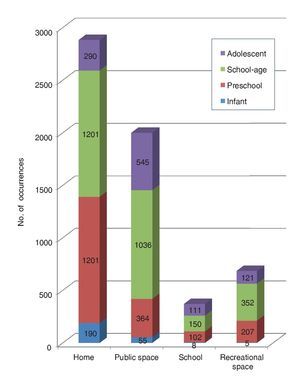

In Mexico, the National Survey of Health and Nutrition (ENSANUT, 2012)19 reported that, according to the report by the mother or caregiver, 4.4% of the children had suffered nonfatal accidents in the last year, with a greater frequency in males than in females (5.3 and 3.4%, respectively). The distribution by mechanism is shown in Figure 1.20 According to the Ministry of Health, in 2010 there were 367,186 hospital discharges reported due to external causes (accidents, poisonings and intentional injuries) only in public hospitals,21 including all age groups.

Figure 1. Percentage of injuries according to age group and type of injury (Mexico, ENSANUT 2006).

A recent report conducted in seven public hospitals in an urban setting of our country, including persons of all age groups, showed that accidental injuries are more frequent than intentional injuries (ratio 4:1).22

A case study of a general hospital in the northern Mexico showed that accidental injuries predominated in male pediatric patients. Nearly half of the injuries took place in the home, and Saturday and Sunday were the days with increased frequency of service requests. A fall was the most frequent mechanism of injury in 46.7% of cases, and the head and upper extremities were the most frequent sites of injuries.23

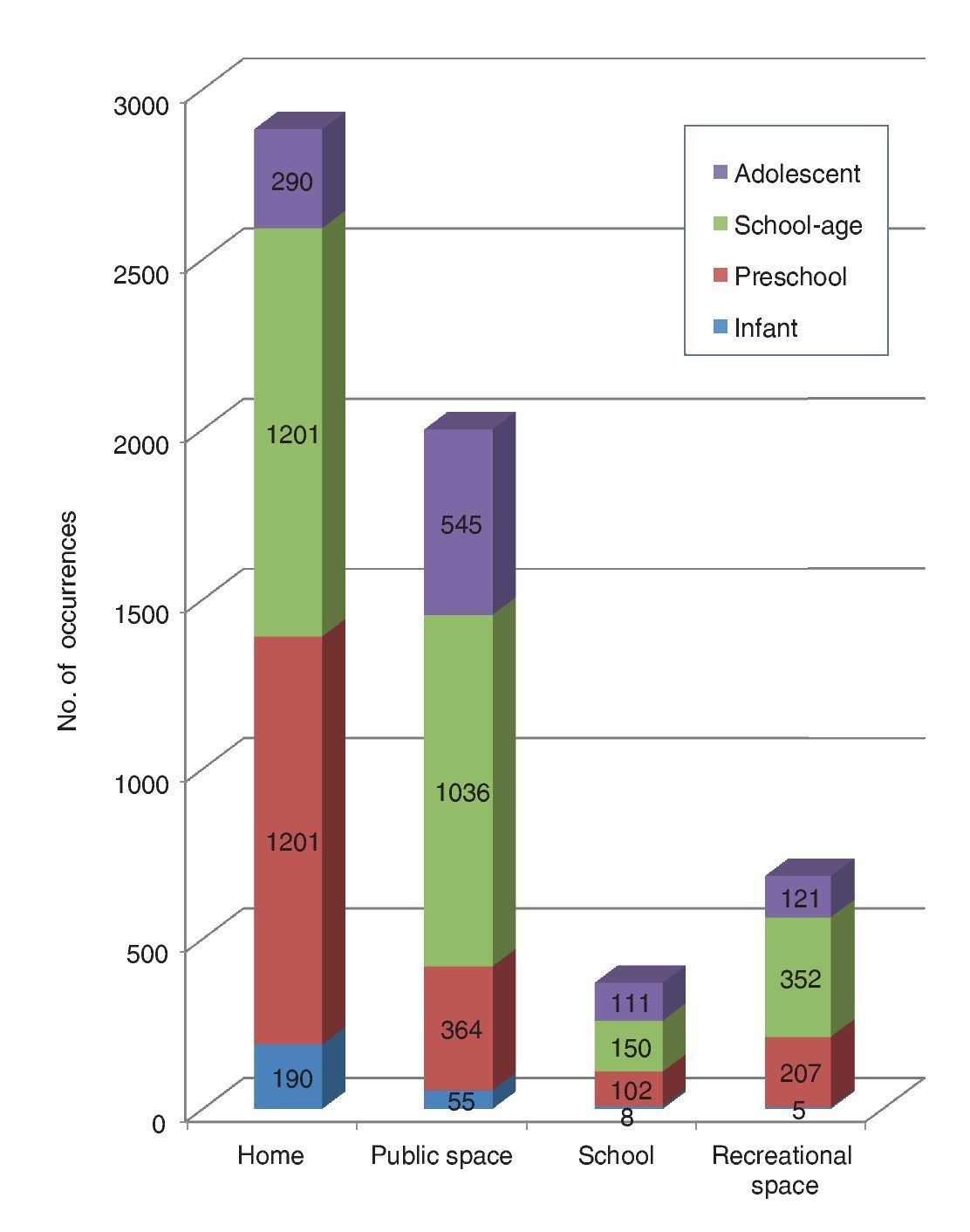

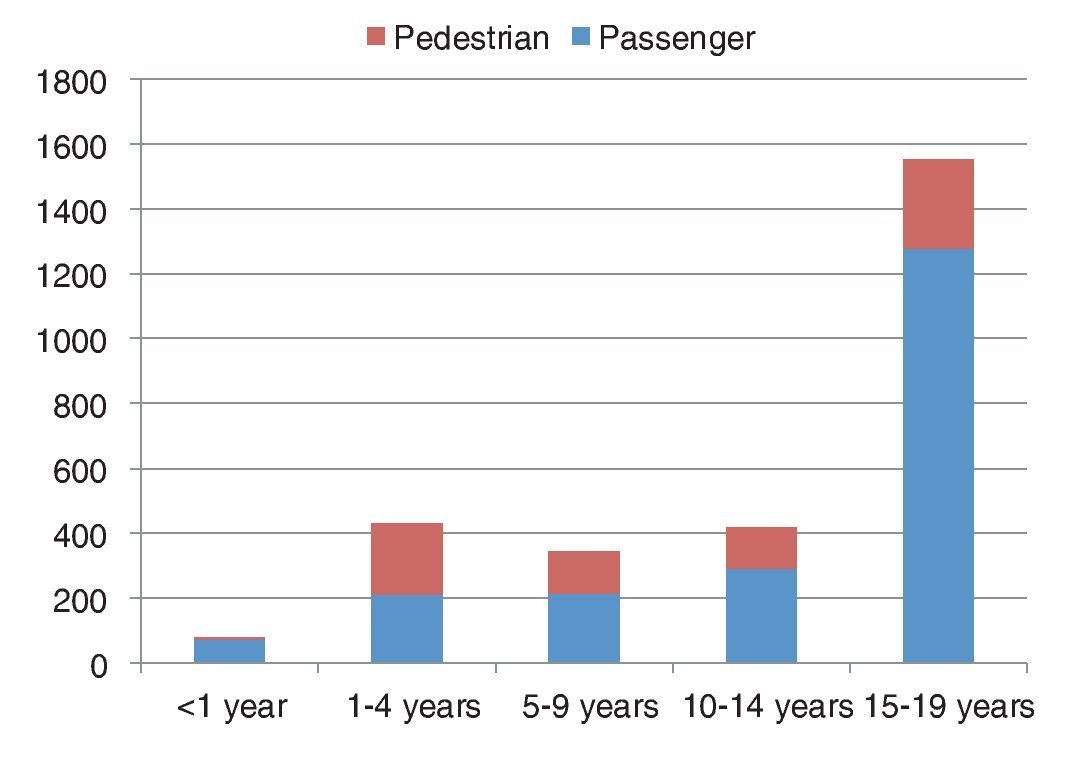

Another report, which included only pediatric patients who required hospitalization in a specialized trauma hospital in Mexico City showed the prevalence of accidental injuries occurring at home followed by injuries from accidents on public roads; the exception was the group of 12-to 15-years of age in whom events occurring on the road predominated (Fig. 2). The presence of work-acquired injuries in 0.8% of the cases is noteworthy even though it was in a group <15 years of age. In this study, upper extremity injuries were predominant over head injuries. Once again, the male gender surpassed that of the female gender.24 Traffic accidents occupied a significant percentage. Official reports show that, in Mexico, both in urban as well as suburban areas, there is a tendency towards an increase in the yearly number of traffic accidents in the last 10 years.25 From the ENSANUT survey 2012,19 16.7% of accidents (for all ages) corresponded to traffic accidents. Analysis of the results of the survey showed interesting results: generally males and urban population predominated. The higher the socioeconomic level, the more frequent are passenger vehicle accidents, whereas pedestrians being run over are most frequent as the lower the socioeconomic level, the risk of traffic accidents is almost four times higher in the group of 10-to 19-years of age than in those <10 years of age.26

Figure 2. Distribution of injuries requiring care in a traumatology hospital, according to age group and location of occurrence. Excluded were work-related injuries (n = 5987 children).

5. Mortality

According to the WHO, each year 950,000 children die worldwide as a result of injuries, and ∼90% of the cases are due to accidents.1 Except for injuries caused by burns, in all categories the male gender predominates over the female.

Internationally, accidents occupy an important place as the cause of death. In general, in the pediatric population, the predominant mechanism of accidental death is traffic accidents followed by drowning deaths.1 Drowning and road accidents occupy eighth and ninth place, respectively, in the 1-to 4-year-old age group. Traffic accidents are the first cause of death in the 15-to 19-year-old age group and the second cause of mortality between 5 and 14 years of age, surpassed only by lower respiratory tract infections.1

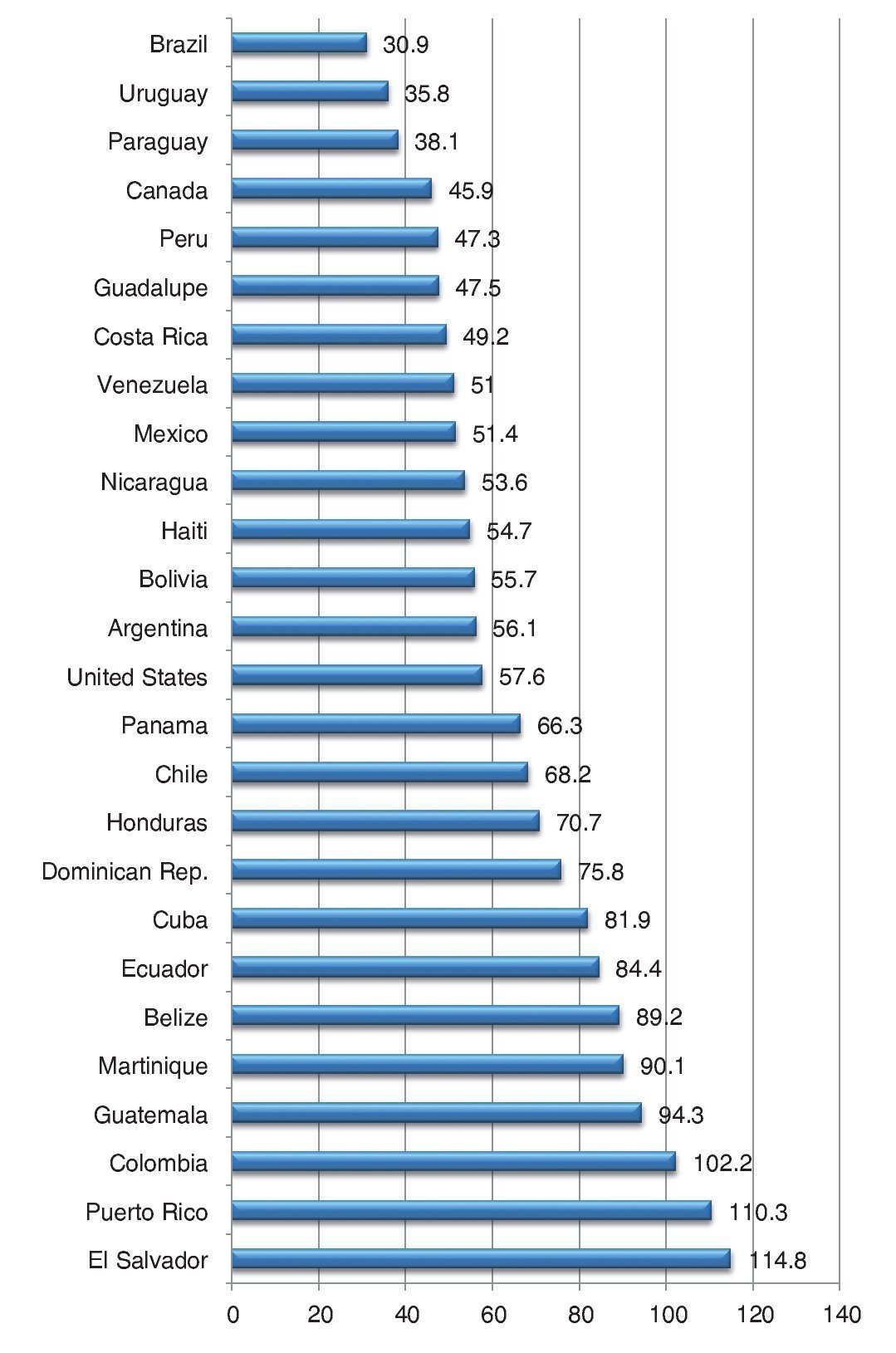

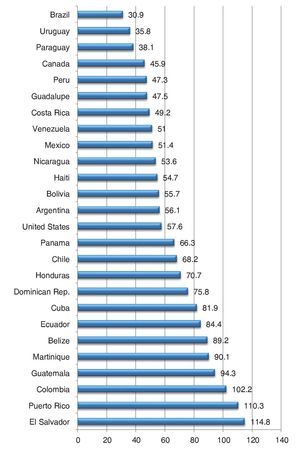

After analyzing deaths due exclusively to traffic accidents, WHO reported a mortality rate of 20.1/100,000 inhabitants per year in countries with intermediate economic status, a group to which the majority of Latin American countries belongs. These figures are more than double of that recorded in wealthy countries.27 On a regional analysis, according to PAHO,28 the mortality rate due to external causes in all age groups varies widely among different countries. In Mexico, a rate of 60.5/100,000 inhabitants was reported during 2010 and occupies an intermediate place with respect to other Latin American countries28 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Mortality due to external causes in different Latin-American countries. Adjusted rate per 100,000 inhabitants (Panamerican Health Organisation, 2009).

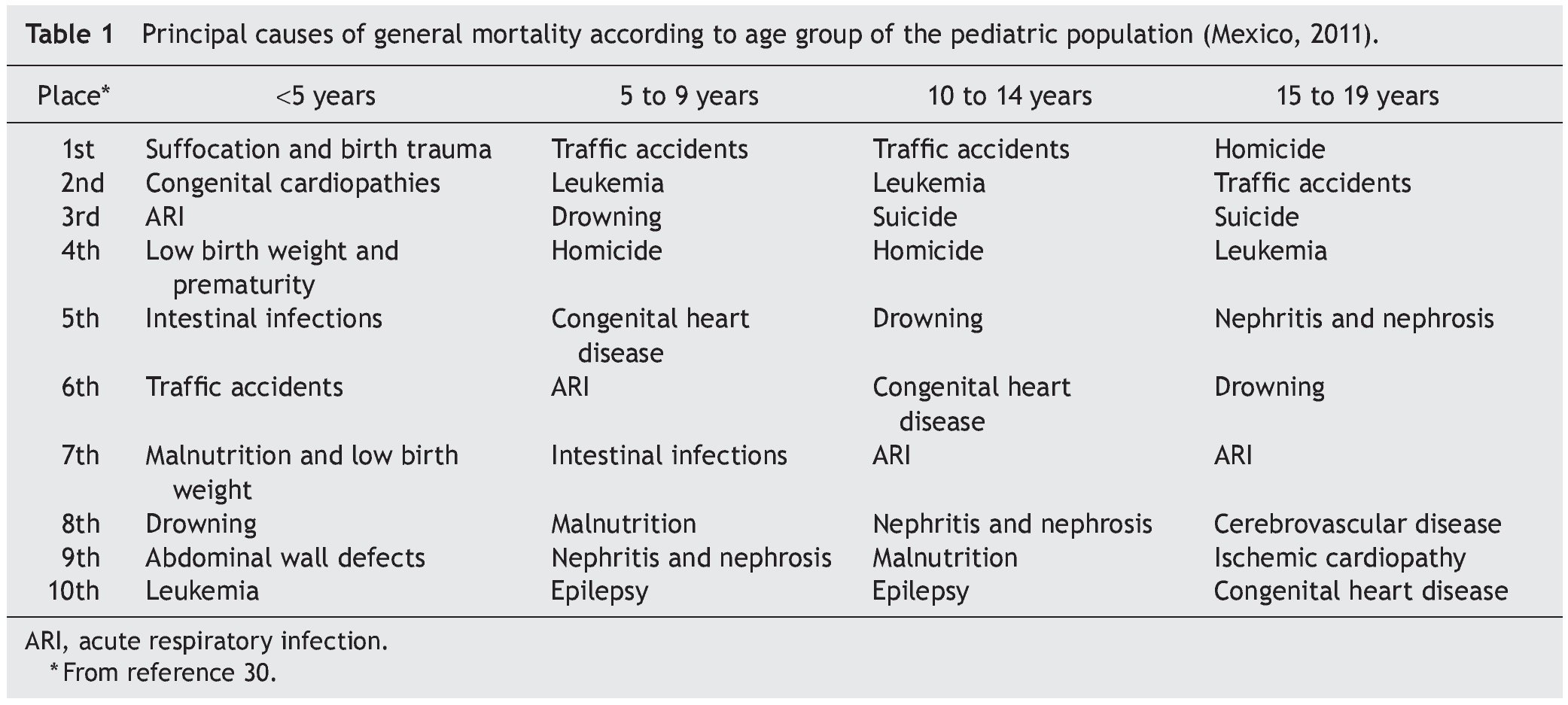

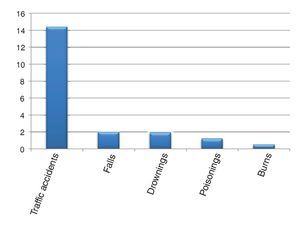

In Mexico, during the period of 2003-2007, there was an average of 53,480 deaths annually due to injuries, taking all age groups into consideration.29 Of these, 72% were accidental. Approximately 12% of the deaths occurred in children <14 years of age.29 With respect to the mechanism, in 2011 the mortality rate due to traffic accidents was 14.4/100,000 inhabitants (Fig. 4).30 Some categories, such as death by drowning, have tended to decline in recent decades.31

Figure 4. Mortality due to accidents according to mechanism (per 100,000 inhabitants). Includes all age groups.

The regional mortality rate by injury is very heterogeneous. According to recent records of the office of the Ministry of Health29 the states that showed increased mortality due to external causes during 2007 were Guerrero, Nayarit, Zacatecas and Michoacan, and the states with lower mortality rates from this cause were Chiapas, Nuevo León, Coahuila, Veracruz and Mexico City.

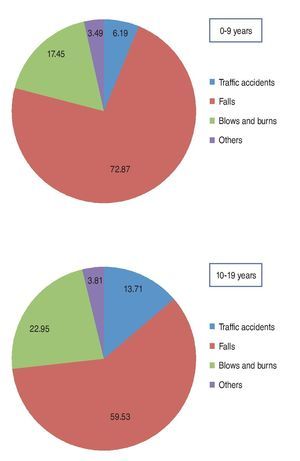

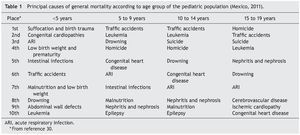

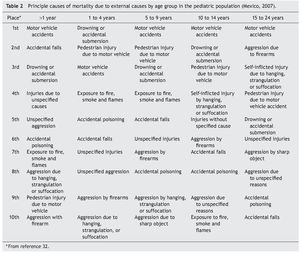

The order that injuries occupy as cause of mortality varies between adults and children. In the latter it is also different, depending on the age group (Table 1).30 In general, accidental mechanisms outweigh intentional ones, although in the group >10 years of age homicide and suicide occupy preponderant places. Table 2 shows pediatric mortality due exclusively to external causes.32 Traffic accidents predominate as the first cause in all age groups except for the group of 1-to 4-years of age. Drowning and injuries to pedestrians by motor vehicles occupy very important places in all groups. Finally, intentional injuries (homicide and suicide) take on greater importance as age increases. Mortality rate trends according to injuries have practically not changed in the last years.29

6. Mortality due to traffic accidents

Accidents related to vehicles represent an important world health problem. Deaths due to road accidents are particularly frequent in countries less economically favored where the global economic cost is estimated at 65 billion dollars annually.33,34 Mortality rates due to road accidents vary widely among regions. Mexico is found among the highest rates of the continent.35

The global trend is the increase in the number of deaths from road accidents, predominantly in poorer countries where the number already exceeds that in industrialized countries.34 The arguments to explain the predominance of accidents in less economically favored countries include the greater proportion of pedestrians and persons who utilize vulnerable vehicles (bicycles, motorcycles, ATVs), inappropriate road design, less frequent use of protective head gear, safety belts and special car seats for infants; lower budgets for campaigns to promote trauma prevention caused by traffic and lower culture of the population in general in terms of road safety.1

Worldwide, urban traffic accidents are more frequent than rural, although the fatality rate is higher for the latter, probably due to the speed of the vehicles on the roads.

In our environment, road accidents occupy first place as a cause of accidental deaths in almost all age groups.32 One report of cases of deaths due to traffic accidents in the state of Nuevo Leon, without age differentiation, showed a predominance of events in the metropolitan area and with a frank superiority in males. It should be highlighted that, according to the blood analysis, almost half of the drivers who were fatal victims had detected alcohol levels.36

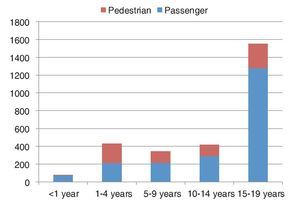

With regard to the pediatric population, in the poorest countries there is greater infantile mortality due to traffic accidents than in rich countries due to the lack of road culture. In Mexico, during almost all throughout the pediatric age, traffic accidents occupy first place as cause of death by external causes. This is true both for accidents that occur by occupants of a vehicle as for the pedestrians who are injured by vehicles (Fig. 5).30,32 It is noted that the figures are more elevated in the adolescent group.

Figure 5. Mortality due to transit accidents according to age group. Rate per 100,000 inhabitants (National Council for Accident Prevention, 2013).

Traffic accidents continue to be a challenge in our country. The educational role of the general practitioner and pediatrician plays a major role. Whereas there is underreporting of road traffic accidents, a recent estimate showed that the actual figure could be more than double.37 An additional factor is that there is no specialized pediatric trauma facility that ensures the complete care of severely injured children.

A particular case of traffic accidents is the "all-terrain" vehicles (ATVs) used for recreational purposes, which are especially dangerous. Although there is no specific statistical information in Mexico, it is known from North American reporting, the importance that they represent as a cause of morbidity, mortality, and disability.38

Accidental injuries in children represent an important and growing public health problem in Mexico as in the rest of the world. The pediatric patient is prone to this type of injury, and their response is different compared to the adult. Frequently, the physiological response to trauma is particularly intense in the pediatric patient. An accident gives rise to significant social, economic and medical consequences. With regard to the latter, the effect can be not only of morbidity or mortality but also of changes in the pattern of growth and development of the child.

The circumstances surrounding accidents often are predictable and preventable, which allow for primary preventive measures. Statistics show how external causes of morbidity and mortality occupy proportionately more important places in the epidemiologic spectrum of children. Although traumas are the most frequent as the mechanism of injury in all ages, other categories such as poisoning, drowning, and burns show figures that are not to be ignored. The physician responsible for pediatric patients should be conscious of the importance of accidents as a cause of morbidity and mortality, of the differences between adults and children and of the need for knowledge and updating on the management of these types of injuries. Finally, the physician should keep in mind the role that the physician plays as an educator for the family in terms of accident prevention. Due to the importance of this topic, it would be desirable and necessary to have additional and better research studies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 22 October 2013;

accepted 12 December 2013

* Corresponding author.

E-mail: edgarbus@yahoo.com.mx (E. Bustos Córdova).