Summary of the clinical history (A-11-35)

We present the case of a female patient 4 years and 4 months of age referred from a second -level hospital due to complex heart disease and esophageal atresia.

Perinatal and pathological history

The patient was a product of G1 with regular prenatal care. She was born by cesarean section due to oligohydramnios with a birth weight 2400 g, length 48 cm, and Apgar 8/9. Esophageal atresia and cyanosis were noted at birth and she was transferred to a pediatric hospital where a gastrostomy and left cervical esophageal fistula were performed. Extreme tetralogy of Fallot was detected and a Blalock-Taussig fistula was created.

Current illness

March 4, 2009 (Admission). At 1 year and 11 months she was referred to the Hospital Infantil de Mexico Federico Gomez (HIMFG). Outpatient cardiology visit initiated approach with EKG, echocardiogram, chest computed tomography and cardiac catheterization. The case was presented in a medical-surgical meeting to decide if the patient was a candidate for total correction with placement of a valved tube.

August 9, 2010. The patient was electively admitted for the surgical procedure during which a 12-mm right ventricular Hancock tube to right pulmonary confluence was placed, 10 mm ventriculotomy, 7 mm interatrial communication, 2 mm patent ductus arteriosus and ligation. Extracorporeal circulation time was 2 h and 15 min. Clamp time was 1 h and 40 min. Surgical time was 3 h and 30 min. Intraoperative bleeding was 410 mL. Blood product replacement was begun due to persistence of hypotension. The patient was managed with amines (dobutamine 7 μg/kg/min, dopamine 5 μg/kg/ min, adrenalin 0.35 μg/kg/min). She was admitted to the intensive unit with an unstable status with low cardiac output syndrome (LCOS) as well as persistent bleeding >10 ml/kg/h through the tubes (pleural and mediastinal) despite administration of Factor VII and transfusion of blood derivatives. For this reason, the patient again required surgical exploration. During the first 72 postoperative hours she presented with data of multiple organ failure as a consequence of LCOS and hemorrhagic shock, with coagulopathy, progressive decrease of urinary volume with decrease in the Schwartz index and increased creatinine and hyperurecemia. She was managed with a furosemide infusion with partial response. She also presented persistent data of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and blood count of 3200 leukocytes, neutrophils 36%, lymphocytes 46%, bands 28%, platelets 49,000, procalcitonin 54.47 ng/ml; therefore, coverage with cefepime (150 mg/ kg/day) and amikacin (15 mg/kg/day) was added. The evolution was slow. Programmed extubation was carried out on the sixth day without success. Data of heart failure were once again established and inotropic support was continued. Extubation was once again attempted at 48 h using non-invasive ventilation with positive pressure with good response. However, at 72 h SIRS once again presented. On chest x-ray, right basal consolidation was observed. A new blood count documented leukocyte count of 49,100, neutrophils 89%, lymphocytes 2%, bands 8%, platelets 81,000, C-reactive protein 28.7 mg/dl, with hemodynamic and ventilatory decompensation. Because of this, she was once again intubated and dobutamine was reinitiated at 5 μg/kg/min. Various cultures were performed. Bronchial aspirate for invasive forms was positive for blastoconids and pseudomycelia with progression of the bilateral cottony infiltrates. Liposomal amphotericin was begun (3 mg/kg/ day). The infectious process once again caused a state of shock. She once again required resuscitation with boluses of crystalloid solution of 20 ml/kg and vasopressor support was reinitiated. Meropenem was added to the management scheme (100 mg/kg/day). She presented with sudden pulmonary hemorrhage and deterioration of respiratory status with a restrictive pattern. A new echocardiogram reported ejection fraction of 56%, shortening 28%, paradoxymal septal motion, dilation of the inferior vena cava, tube connection at the level of the branch confluence with gradient of 50 mmHg without causing obstruction, dilation of the inferior vena cava. Candida mannan antigen was reported: 750 ng/ml.

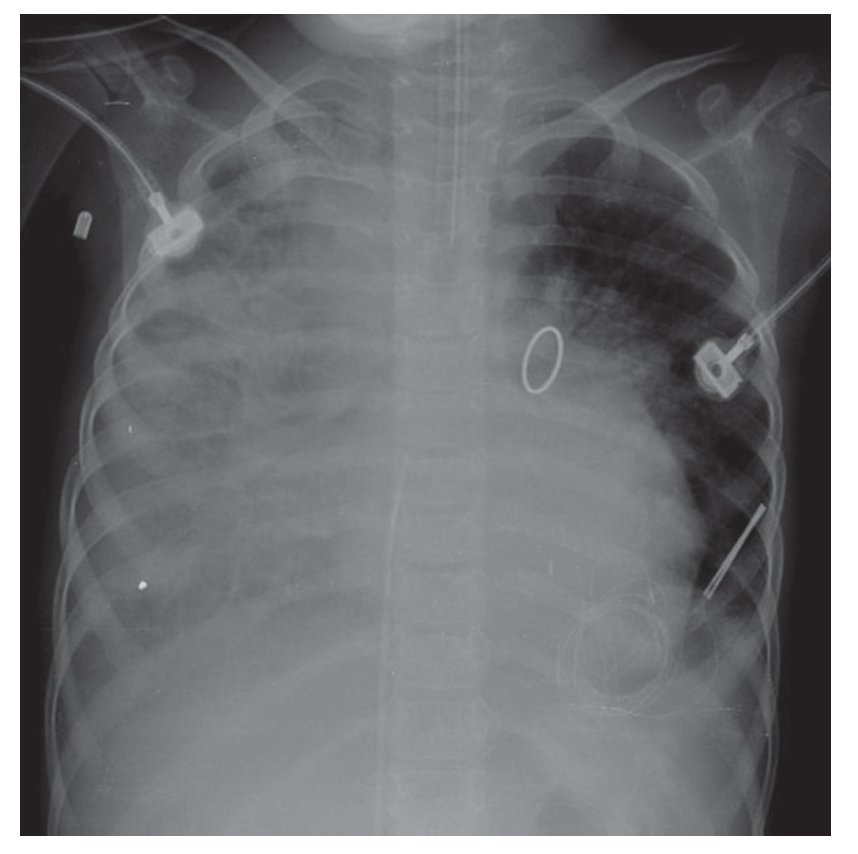

Chest x-ray. Image occupied the entire right hemithorax, air bronchogram without visualization of the costodiaphragmatic angle.

With hemodynamic instability, clinical data were hypodynamia, oliguria, lactate 2, HCO3 16, base deficit -8, venous saturation of 65% and hypotension refractory to fluids.

Dobutamine dose was increased to 8 μg/kg/min. Milrinone was begun (0.7 μg/kg/min) and adrenalin (0.3 mg/kg/min) was added; ventilation with peak inspiratory pressure of 20, positive end expiratory pressure of 7, FiO2 100%, Kirby 60, oxygenation index of 22.

High-frequency oscillatory ventilation was attempted with minimal response and great hemodynamic effect and was changed to conventional ventilation. The patient presented increased urea and creatinine, oliguria, persistent metabolic acidosis, and generalized poor perfusion. She progressed to multiple organ failure and cardiac arrest that did not respond to advanced resuscitation maneuvers.

Case presentation

Imaging (Dr. Mariana Sanchez Curiel)

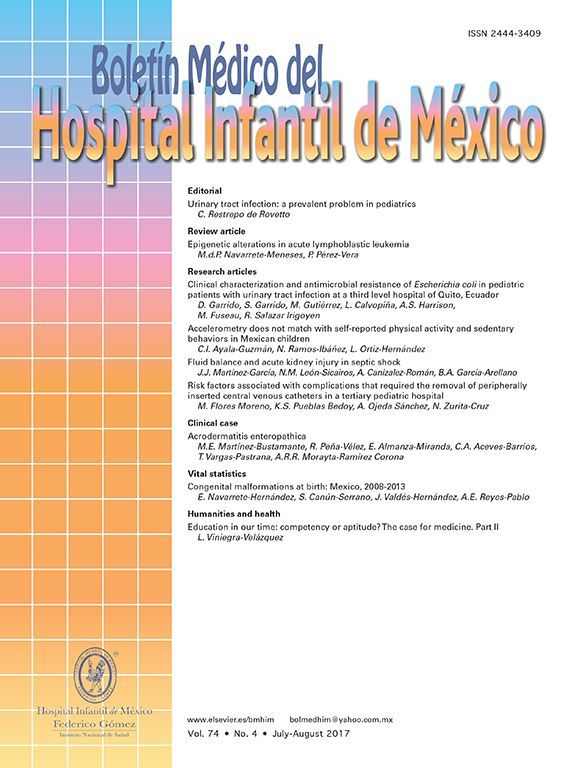

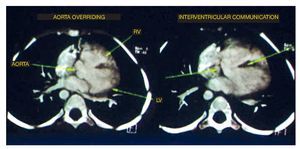

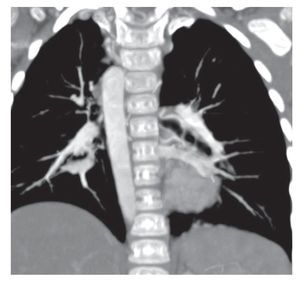

The first study performed was a cardiac angiotomography. The findings were situs solitus, levocardia, adequate venous drainage and atrioventricular concordance and normal ventriculoarterial connection. On axial reconstructions, the four basic findings of tetralogy of Fallot were noted: the emergency of the aorta at the level of the left ventricle and the overriding through the interventricular septum. The septum was observed as the central hypodense linear image, which also showed an important defect in its proximal portion in relationship with an interventricular communication (IVC) as well as in the emergence of the right atrium absence of the pulmonary trunk was observed. However, the right branch and left branch showed adequate caliber and perfusion (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Two of the four components of tetralogy of Fallot are seen: aorta overriding and interventricular communication. RV: right ventricular; LV: left ventricle.

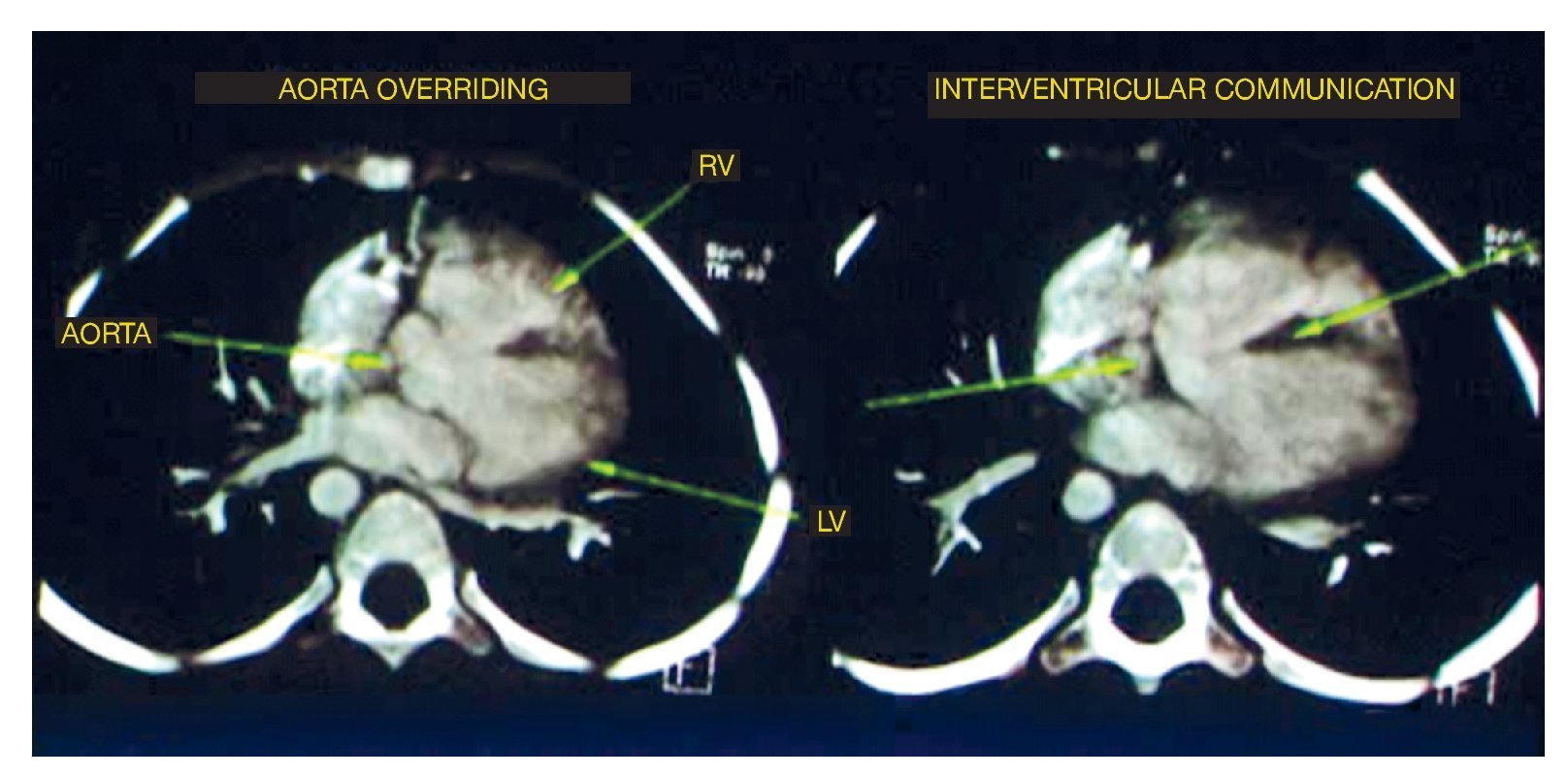

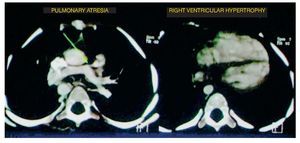

At the level of the most caudal cuts, it was observed that the relationship between the right ventricle and the left ventricle was virtually the same. It should be kept in mind that the left ventricle should be larger in size because it handles pressure and the septum with a concavity. In this case it was found to be straight, indicating right ventricular hypertrophy (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Two other components of tetralogy of Fallot are observed: absence of the pulmonary trunk and right ventricular hypertrophy.

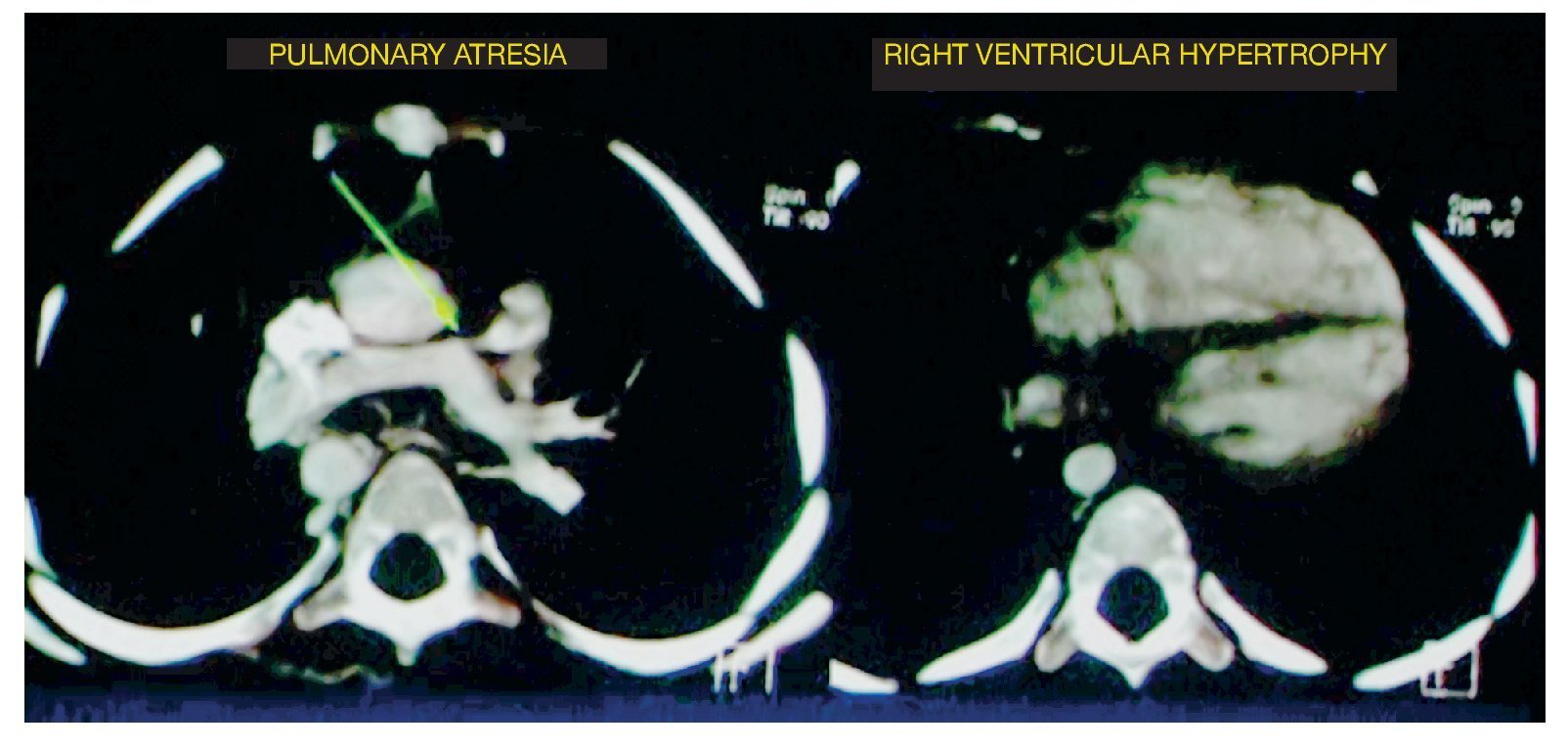

Associated with this was the presence of a right aortic arch. Coronal reconstruction shows the path of the thoracic aorta at the level of the patient's right side. In the volumetric reconstruction it was exemplified better, even from the origin of the arch (Fig. 3). In this scan, it was not possible to assess permeability or the caliber or the trajectory of the Blalock-Taussig fistula.

Figure 3 Right aortic arch.

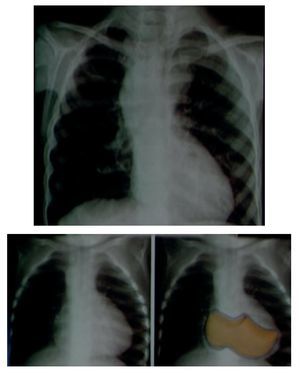

In an anteroposterior (AP) chest film the characteristic silhouette of tetralogy of Fallot is the image of the "Swedish boot." The apex corresponds to the tip and heel to the growth of the right cavities (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 "Swedish boot" image characteristic of tetralogy of Fallot in the AP chest film.

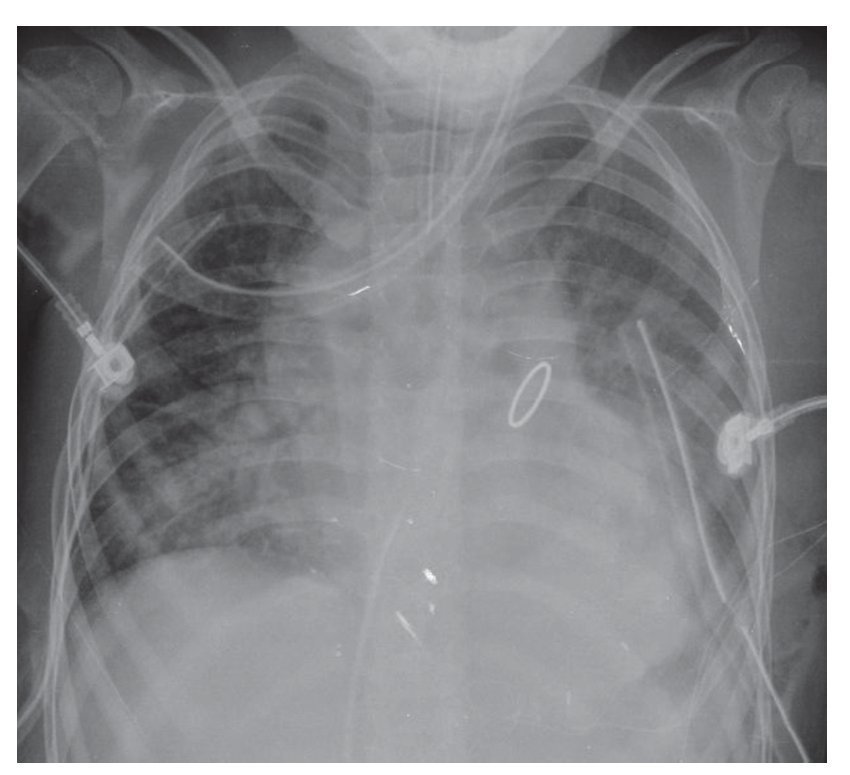

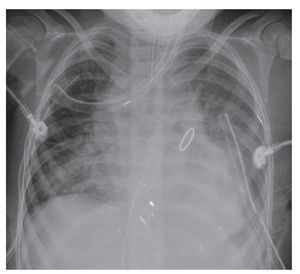

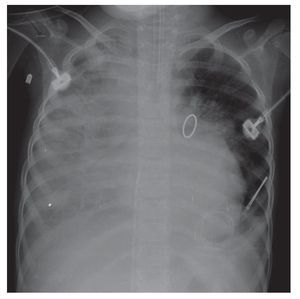

By 2010, a year later, the patient had another AP projection of the chest. The aortic arch of the right side was again visualized. There was a rise of the apex suggestive of the growth of the right cavities and there was prominence of the interstitium in a generalized and diffuse manner. Another important change was an increased cardiothoracic index, i.e., cardiomegaly at the expense of practically all the cavities. This circular, rounded, hyperdense image very probably corresponds to the replacement valve mentioned in the clinical history. The most important finding is a bilateral diffuse alveolar infiltrate was observed occupying the basal region, with greater predominance on the right side and the presence of a bilateral pleural effusion. Also, at the distal end two drainage catheters and an endotracheal tube were observed in adequate position above the carinal bifurcation (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 Postoperative AP x-ray of the chest.

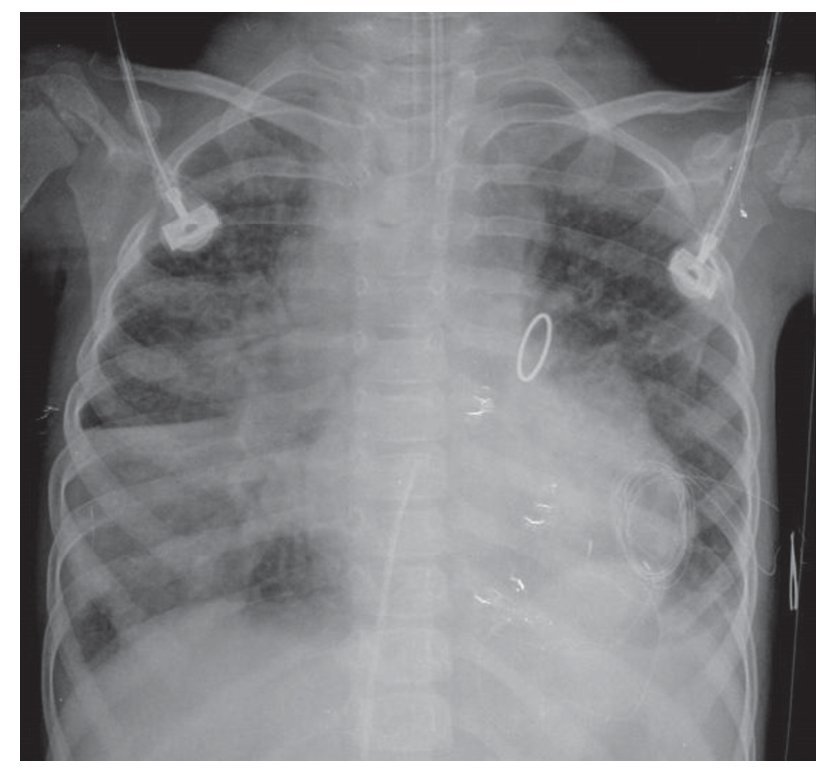

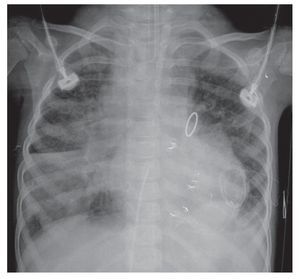

The evolution of the image showed the organization of the right basal consolidation, which became more evident. In fact, it was found associated with a passive ipsilateral atelectasis. Bilateral alveolar congestion was much greater and erased from this side the ipsilateral angle. The patient very probably already presented data of pulmonary overload, i.e., edema (Fig. 6). In this last x-ray, the "hairy heart" image was observed, which is the bilateral prominence of both hilum, an image characteristic of edema vs. hemorrhage. Also, there was total occupation of the right hemithorax by this white lung, which may be related with the above-mentioned consolidation (Fig. 7).

Figure 6 Right basal consolidation and bilateral alveolar congestion.

Figure 7 Progression in pneumonic process with bilateral prominence in both hilum (suggestive of bleeding), as well as total o ccupation of the right hemithorax.

Echocardiography (Dr. Paola Vidal Rojo, Cardiology)

The study performed confirmed the diagnosis of tetralogy of Fallot with all its components: aortic overriding, ventricular septal defect, pulmonary valvular stenosis and hypertrophy of the right ventricle, as well as right aortic arch (associated with tetralogy of Fallot in ∼25% of children), right ventricular pressure of 40 mmHg, preserved systolic function and a permeable Blalock-Taussig fistula.

Discussion

Department of Thoracic Surgery and Endoscopy (Dr. Gustavo Teyssier Morales)

The case of a 4-year-old female patient is discussed. She was referred from a pediatric hospital from the State of Puebla to this institution for the correction of tetralogy of Fallot.

The patient was the product of a 24-year-old mother and 37-year-old father with no clinically significant past medical history. Pregnancy was medically monitored. She was the product of a first pregnancy, weight 2400 g, with an Apgar score of 8/9. Esophageal atresia was detected at birth. It was apparently a type I esophageal atresia, indicating that the patient had two blind esophageal points without connection with the airway; therefore, at birth an esophagostomy and gastrostomy was carried out without thoracic approach. It should be remembered that, generally, in patients with type 1 esophageal atresia, the gap between the two esophageal ends is wide, which makes the primary esophageal surgery impossible in most cases.

The patient was also diagnosed with tetralogy of Fallot in the referral hospital. At 5 days of life, she was operated with a Blalock-Taussig pulmonary system fistula without complications.

The patient was treated in the outpatient cardiology department of this institution from the age of 1 year and 11 months. She was found to have a weight deficit of 15%, grade 1 acute malnutrition (with weight for age in the 50th percentile). She also had generalized cyanosis and a grade 4-5 systolic murmur with fremitus.

Approximately 6 months after her first visit to the hospital an angiography was carried out, which showed confluent pulmonary branches of good size. Chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly and the reduction of pulmonary flow and right aortic arch, and echocardiogram reported characteristics of tetralogy of Fallot, with pulmonary infundibular stenosis with Z-value score of -7, growth of the right cavities and with normal pulmonary branches, the Blalock-Taussig fistula was permeable. Images were suggestive of pleural collaterals.

At 3 years and 4 months of age, catheterization was done and the Blalock-Taussig fistula was found stenosed at its pulmonary origin with a better diameter in the extreme subclavian end. Its flow was low and slow. Pleural flow circulation was found, and the case would be presented during the surgical meeting for the correction.

One year later, on August 9, the patient was admitted to surgery where correction was done with a valve tube. An abundant collateral network was found, pulmonary artery trunk of 3 mm, right branch of 7 mm and left of 6 mm, and IVC by misalignment of 8 mm. A Hancock valved tube was placed from the right ventricle to the confluence of the pulmonary branches. A 3-mm IVC was left and the PCA was closed. As a first complication there was intense hemorrhage that conditioned shock requiring a new surgical exploration.

It is necessary to take into consideration various factors that may have influenced the poor progression of this patient and somewhat explain the postoperative bleed. First, it must be taken into account that the patient is 4 years of age and passed through a chronic state of hypoxemia, secondary to which different coagulation disorders can occur such as decrease in the platelet count and platelet function disorder. There is also a deficit of coagulation factors dependent on vitamin K, factor V, an increase in fibrinolytic activity and deficit of Von Willebrand factor. Second, massive bleeding should be considered. The patient bled approximately three circulating volumes during the surgery, which were replaced with reconstituted fresh, concentrated plasma, erythrocytes, platelets, albumin and crystalloids. The effects of massive transfusion are well known and diverse, ranging from coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia, secondary to dilution and to the deterioration of coagulation factors of the units preserved, up to electrolytic disorders such as hypocalcemia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, lung damage secondary to massive transfusion, renal damage secondary to massive transfusion, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, multiple organ failure and even death.

It should be remembered that, in addition to adverse events that are observed in the postoperative period of cardiac surgery, there is the systemic inflammatory response induced by the contact of the systemic circulation with the extracorporeal circulation system, which causes complement activation, activation of neutrophils, release of cytokines that cause disorders in the microcirculation, coagulopathies, fever and organ dysfunction. These factors together constitute a post-perfusion syndrome. The last factor to take into account as a cause of bleeding in our patient is the great collateral circulation found during surgery as a result of the chronic hypoxemia suffered in the years prior to the correction of her pathology.

During the first 5 postoperative days the patient progressed slowly towards improvement, with high arterial saturations that showed an adequate pulmonary perfusion and good function of the valved tube, which allowed for a decrease in the aminergic contribution. Antimicrobial coverage was begun with cefepime and amikacin because she once again presented a systemic inflammatory response. She developed a pleural effusion of 190 mL; therefore, a right pleural tube was placed. There was no cytochemical analysis or a description of the fluid obtained, which would have guided one to know if the patient had developed a parapneumonic infectious effusion or a transudate secondary to alteration in the hydrostatic pressure in a patient with hemodynamic instability who had received such intravenous fluid volumes.

On August 15, a scheduled extubation was attempted, which failed because of ventilatory and hemodynamic instability. Finally, 4 days later extubation was achieved. The patient maintained central venous pressures between 5 and 7, partial pressures of oxygen on blood gases of >60, which indicated adequate perfusion and functioning of the valved tube.

Four days later the patient started with SIRS, 49,000 leukocytes, 90% neutrophils, bandemia, thrombocytopenia and fever, evolving towards septic shock. She again required endotracheal intubation and aminergic support. Coverage with vancomycin was initiated because of a probable skin infection. Invasive forms were reported in the urine and bronchial aspirate for which liposomal amphotericin was begun. In the following week, hemodynamic deterioration secondary to septic shock continued and required even greater ventilatory support. Antimicrobial coverage was broadened with meropenem until finally, on August 28, the patient presented a mixed shock, multiorgan failure and died.1,2

With respect to the renal evolution the patient presented from the preoperative phase, there was chronic cardiorenal syndrome secondary to renal hypoperfusion, which led to the gradual deterioration of kidney function. Also, during the postoperative period the patient had multiple risk factors for presenting renal insufficiency, such as massive bleeding, massive transfusion, prolonged hypotensive state, state of shock and sepsis. From the early postoperative period she had data of renal insufficiency secondary to acute tubular necrosis, oliguria that was treated with diuretics and, although she apparently improved during subsequent days, it may have been a polyuric phase to renal insufficiency that resulted in a clearly established renal insufficiency as she presented nitrogen retention, metabolic acidosis and hypervolemia. It seems that this patient should have received some dialysis management from the early stages of renal failure. However, and although it is not established in the summary, it was not initiated, possibly due to lack of slow-exchange dialysis methods that would have been ideal in the hospital.

With all the previously mentioned data, the final diagnoses are as follows.

• Congenital cyanotic cardiopathy (tetralogy of Fallot type)

• Esophageal atresia type 1

• Surgical intervention for Blalock-Taussig fistula, esophagostomy and gastrostomy

• Surgical intervention for total correction with a valved tube

• Fungal sepsis with pulmonary focus

• Acute renal failure

• Septic shock and cardiogenic shock

Coordinator (Dr. Maribelle Hernandez Hernandez)

It is important to emphasize that the best chance these patients have is an early referral so that the methods of assessment and intervention are also timely and a number of complications can be avoided. In the specific variant of this heart disease, the varying anatomic diversity forced a more diligent evaluation, with various imaging studies carried out by the cardiology service.

Cardiology (Dr. Inaki Navarro Castellanos)

The majority of these types of patients experience a late referral to the hospital. Management in this case began when the patient was 1 year and 11 months old with two complementary diagnostic studies: tomography and later catheterization.

Currently, most centers carry out only one study and the best is catheterization. If there is a prior study required to evaluate the anatomy, magnetic resonance is recommended because it decreases the risk of radiation.3

On the other hand, this patient had preoperative risk factors. Some were not ruled out such as the possibility of some genetic factor, e.g., a 22q11 lesion that is associated in up to 22% of patients with tetralogy of Fallot.4 In the hospital's experience, the mortality is also not high (∼10%).

Coordinator (Dr. Maribelle Hernandez Hernandez)

During this patient's evolution, different complications were presented. Without a doubt, what made a difference were the infectious processes. The opinion of the Infectious Disease Department was requested with regard to the treatment scheme the patient received and, as a second point, in those children who are subject of intense trauma and stress, how was the postoperative period of this patient where an SIRS developed early. How can one determine the presence of an infection to offer timely diagnosis and treatment?

Infectious Diseases (Dr. Martha Josefina Aviles Robles)

With respect to the antimicrobial coverage, one must always classify whether it is an early or late nosocomial infection associated with the ventilator because this indicates the causative microorganisms. In this patient who had a late pneumonia, it was very important to provide coverage for Gram-negative bacilli, particularly for Enterobacter, Pseudomonas and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. All the reports in the international literature mention these microorganisms as the most common. They vary with regard to the frequency, depending on the flora that predominate in the hospital; however, when faced with a nosocomial pneumonia, coverage for these microorganisms should be provided.5

If the progression is not adequate, one must also consider the epidemiology of the hospital itself. One important matter is that at present there are more multiresistant bacteria reported, especially Pseudomonas. It has also been present in the HIMFG. Another point is that, at this time it is not a problem in the HIMFG, we should consider microorganisms such as Acinetobacter, which are more common in nosocomial infections, mainly in intensive therapy, in patients with multiple lines and in patients with complex and extensive surgeries.

With regard to the empiric coverage that was begun, fourth-generation cephalosporin plus aminoglycoside is the therapy that, in general, is currently recommended. This could vary depending on whether there is a greater incidence in the hospital of a specific type of bacteria. Otherwise, the scheme mentioned is initiated and one can progress to carbapenem.

In the case where another type of microorganism is suspected, such as in this case when cellulitis was suspected, the coverage should be widened for Gram-positive cocci and even with the indirect evidence that the patient had yeast, empiric coverage should be added.

With regard to the inflammatory markers that can provide evidence to suspect an infection vs. the metabolic response that is so important after surgery, there are various studies. The most useful marker is procalcitonin. In general, other markers have been studied such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and interleukin-8. At present, other molecular techniques are being used such as micro-DNAs or bacterial fragments that may perhaps be useful; however, they are still far from being able to be applied on a day-to-day basis.

With respect to procalcitonin, it is important to know that although its orientation is toward the presence of a bacterial infection, it has also been documented to be elevated (although in low ranges) for other reasons, notably pancreatitis, trauma, burn patients, and extensive surgeries, among others. With all this, what has been seen is that cut-offs can be suggested to consider the probability of a bacterial infection. Generally, at <0.2 pg/ml bacterial infection is less likely. From 0.2 to 2-5 pg/ml, bacterial infection is probable. However, practically all studies note that when it is found to be >5-10 pg/ml the possibility is very high and could support the suspicion of a bacterial infection. This is always correlated with the clinical and radiological progression. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S.) and other organizations such as the Latin American Academy of Pediatric Infectious Diseases are based on clinical and radiological criteria and, above all, on the amount of leukocytes and on the microbiological evidence to support the diagnosis of nosocomial infection. They are not yet supported on the determination of the procalcitonin concentration as a frank evidence of infection, although it is the most investigated marker so that in the future it can be of greater diagnostic support.6-8

Findings from the Pathology Department (Dr. Mario Perezpeña Diazconti)

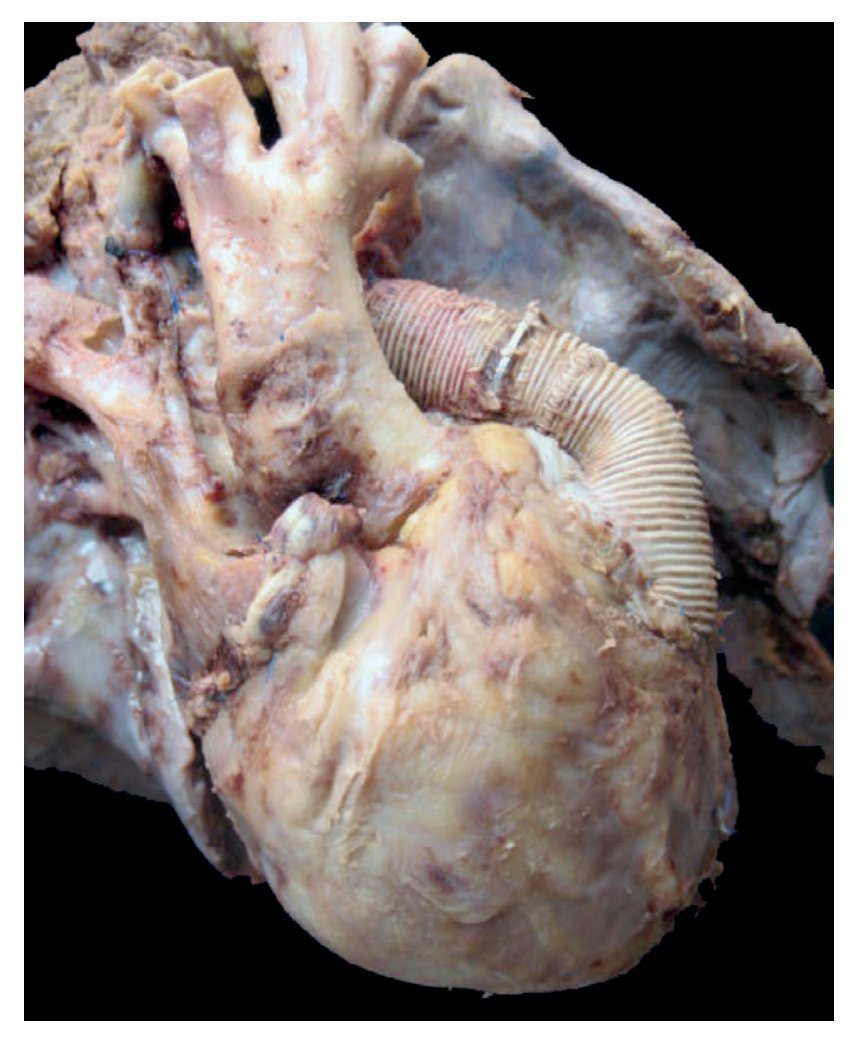

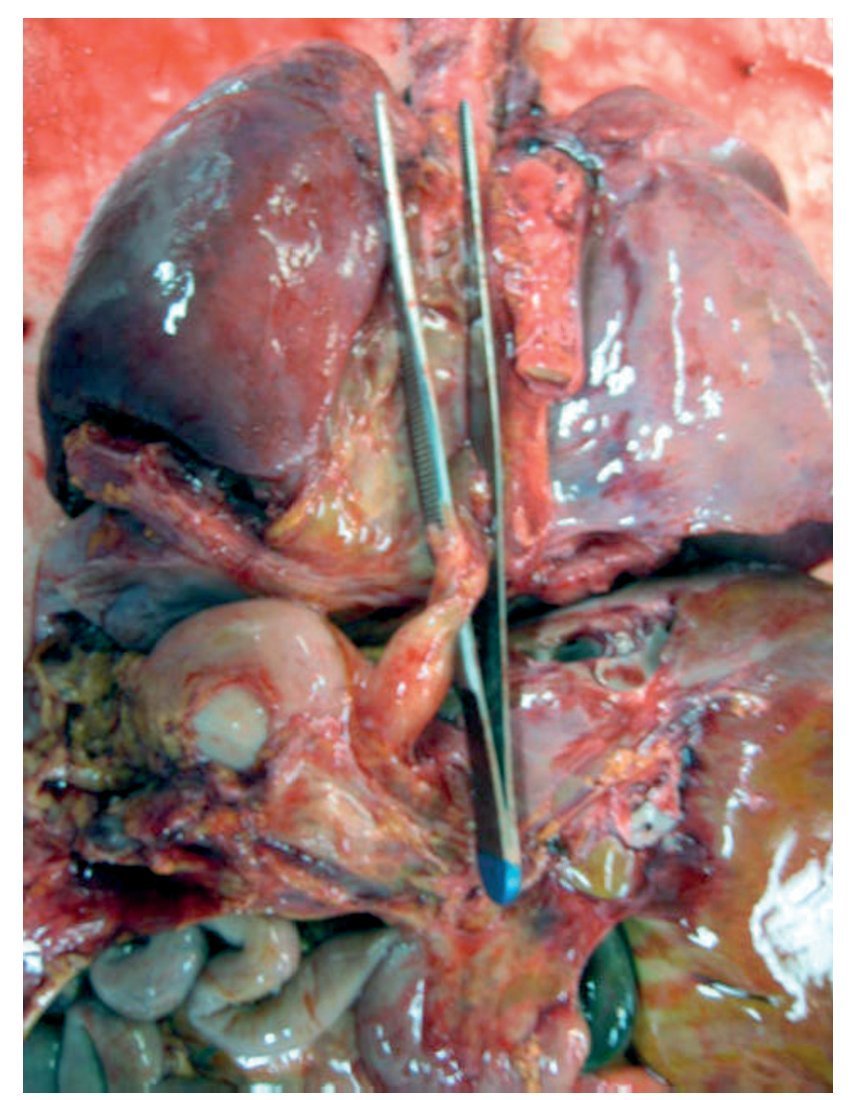

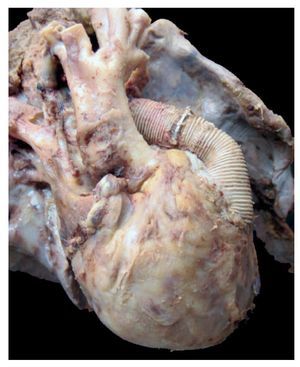

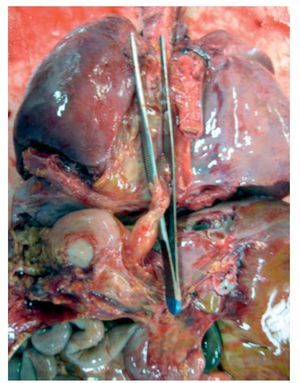

In the first place, the findings from the heart are shown, although in the case of this autopsy, it was not the organ with the main damage. The entire cardiopulmonary block was found to be increased in size and weight; the two lungs with an observed weight of 650 g with an expected weight of 147 g and the heart weighed 350 g with an expected weight of 77 g. The valved tube with the metallic ring implanted from the ventricle towards the emergence of the pulmonary arteries can be seen, such as was described in the clinical history (Fig. 8).

Figure 8 Heart disease corrected with a 12-mm Hancock valved tube, which connected the right ventricle with the confluence of the pulmonary branches.

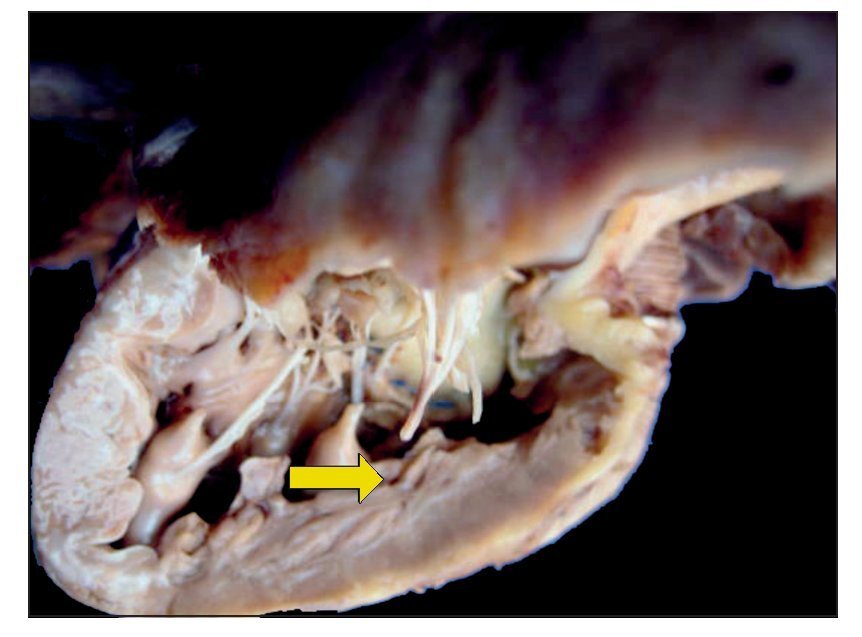

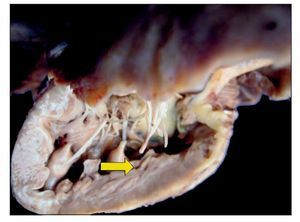

There was no change seen in the sutures, and there was no sign of hemorrhage or clots, i.e., technically there was no problem at the time of the study. Upon opening the cavity, the implant that closed the interventricular communication was able to be seen. There was right ventricular hypertrophy present. One can observe, at the bottom, the interventricular patch and wall hypertrophy (Fig. 9).

Figure 9 Repair of the 7-mm interventricular communication with a patch of pericardium (arrow).

Histologically, the right ventricle showed nuclear polymorphism, some hyperchromic nuclei, and mild edema related with hypertrophy. In the left ventricle, some edema was also seen between the myofibrils and there was some change in the size and shape of the nucleus, also due to hypertrophy.

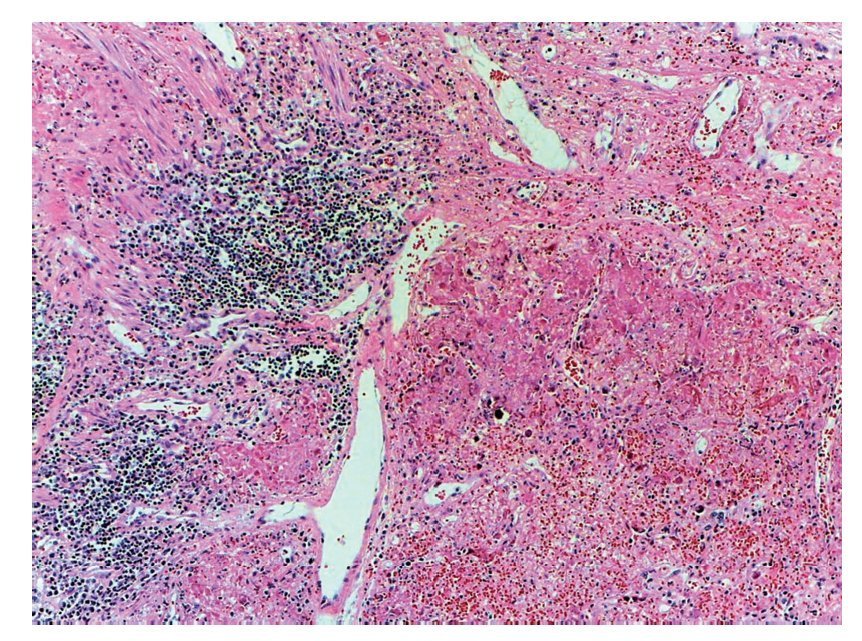

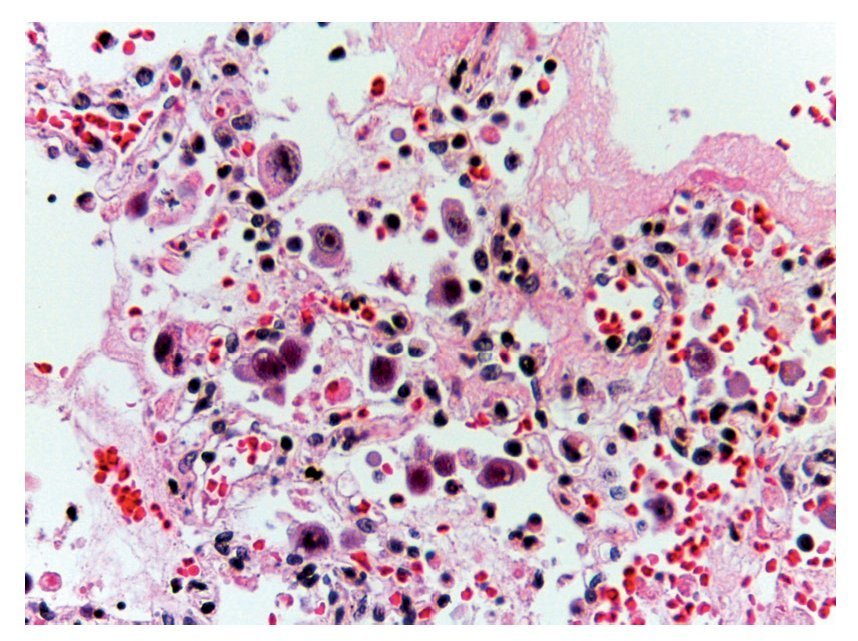

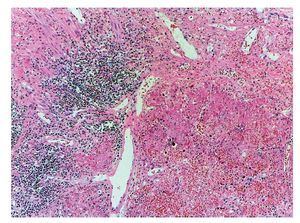

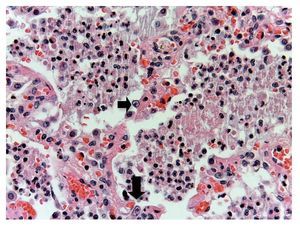

However, the most important damage is in the lungs. There is a solid-appearing surface with extensive reddish-brown areas and other areas of gray or clear brown color representative of very severe damage, which is a necrotizing pneumonia that affected practically the entire right lung. The remnant of the bronchiole was seen where the detached epithelium is noted. This eosinophilic material occupies the lumen and in the remainder, as can be seen, the lung parenchyma is not recognized. There are extensive hemorrhagic areas associated with intense zones of mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. In other areas, noting that the entire lung parenchyma is necrosed, the lung is not recognizable. There is a severe pneumonia with areas of recent hemorrhage (Fig. 10).

Figure 10 Necrotizing pneumonia. It was not possible to identify the pulmonary morphology due to extensive necrosis caused by the etiologic agent. In addition, areas of recent hemorrhage and inflammatory cell clusters were present.

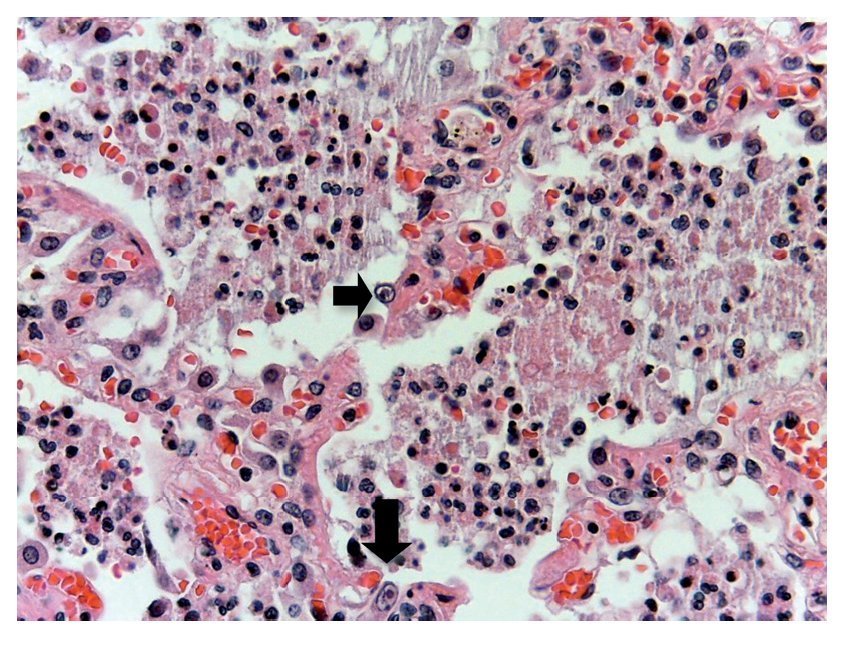

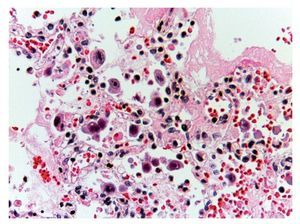

In other areas where some parenchyma is still preserved, it is possible to recognize edema, hemorrhage and other areas with alveolar spaces occupied by inflammatory infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes associated with a bacterial etiology. In other areas, the entire alveolar space is occupied by these polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The presence of these cells that corresponds to cytomegalovirus (CMV) is begun to be noted (Fig. 11). For this reason it is suspected that the origin of this severe necrotizing pneumonia is a CMV. There is a large quantity of these cells in all areas, especially in the areas of necrosis. It practically appears to be a CMV culture. The cells are large, the nucleus is very large with a clear halo and the nucleolus is an intense red color. Characteristically, the cytoplasm shows some blue color granules that also correspond to viral particles (Fig. 12).

Figure 11 Alveolar spaces occupied by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and cellular debris. The presence of large cells with clear nucleus, prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm was noted (arrows).

Figure 12 Abundant cytomegalovirus (CMV) cells. Cells infected with intranuclear large basophilic inclusion bodies and clear halo. The cytoplasm is abundant with small basophilic inclusions; 50% of fatal cases due to CMV pneumonia have been reported.

The liver was found to be increased in size and weight with a yellowish-green color and congestion as data of final shock. The two kidneys were also increased in size and weight and showed extensive congestion in the area of the cortex, presence of some blood cylinders in some tubules and eosinophilic material in their lumen. The area of the medulla, also very congested, and as an effect secondary to the administration of diuretics, the presence of calcifications was extensive. The spleen was increased in size and weight and showed massive congestion. The thymus was decreased in size and with loss of the number of lymphoid elements associated with a final shock event. Contraction bands in the smooth musculature of the digestive tube in the small intestine and colon were also associated with a shock event.

Final anatomic diagnosis:

Principal disease

Congenital malformations characterized by congenital heart disease

• Extreme tetralogy of Fallot

• Esophageal atresia

Concomitant disorders Procedures done outside the HIMFG

• Status post right modified Blalock-Taussig (4-9-2007)

• Corrected esophageal atresia with left esophagocervical fistula (4-9-2007)

• Status postgastrostomy (4-9-2007)

As suspected, on the left side of the lung the alveolar walls can be seen. In this case, with the alveolar space filled with fluid that corresponds to edema, some hemorrhage and other areas where there is emphysema due to wall rupture, causing these large air spaces.

The distal end of the esophagus is seen without communication with the upper part (Fig. 13).

Figure 13 Thoracoabdominal block is shown with the distal end of the esophagus (clamp).

The presence of fungus in the lungs was intentionally sought with Pas and Grocot stains, but there was no evidence of any fungal structure in any cut.

The following was observed in other organs: esophageal remnant with inflammatory infiltrate, esophagogastric junction without any alteration, and esophageal mucosa with some areas of congestion. Histologically, the area of the gastrostomy showed some polymorphonuclear inflammatory infiltrate and the mucosa was found to be preserved, practically without changes.

Procedures done at HIMFG

• Status post-total correction with valved tube (8-9-2011)

• Status post-ligation of the ductus arteriosus (8-9-2011)

• Status postsurgical exploration of the chest (8-9-2011; 23 h) with bleeding at the Blalock-Taussig junction site

• Serohematic fluid in the right pleural cavity (150 ml)

• Serohematic fluid in the peritoneal cavity (20 ml)

• Negative pneumothorax

• Cardiomegaly (PO 350 g/PE 77.5 g)

• Pulmonary atresia

• Interventricular communication

• Right ventricular hypertrophy

• Viral and bacterial necrotizing pneumonia (CMV)

• Nephrocalcinosis secondary to the use of diuretics

• Malnutrition (PO 10, 280 g/ PE 20,000 g)

• Brain atrophy (PO 1,100 g/PE 1,204 g)

• Nephromegaly ( PO 240 g/PE 103 g both kidneys)

• Congestive splenomegaly (PO 65 g/PE 49 g)

Anatomic data of shock

• Acute involution of the thymus

• Ischemic hypoxic visceral myopathy in the digestive tube

• Acute tubular necrosis

Postmortem cultures

• Blood cultures with yeast growth

• Colon with growth of Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Morganella morganii

• Cerebral spinal fluid, lungs, spleen, liver and small intestine without growth of microorganisms

Cause of death

Necrotizing pneumonia due to CMV

Infectious diseases (Dr. Martha Josefina Aviles Robles)

CMV is an ubiquitous virus. The primary infection usually presents itself at early ages. There are several epidemiological studies that report, for example, that in the U.S., at the stage of adolescence, 40 to 60% of the population has immunological memory of the virus and 80% for adulthood. Variations have also been reported depending on race. For example, in these studies, the Hispanic race and Mexican-Americans were colonized in up to 80%.

Another important point is that issues such as overcrowding, conglomerates and poverty favor transmission or infection at younger ages. In Mexico, at the age of 3 years, ∼90% of the population had their "first contact" with the CMV. It is said "first contact" because the most frequent manifestations of the infection is asymptomatic; generally we become infected because we do not manifest the disease. As is known, this is a virus that remains latent for life in the organism. In immunocompetent subjects, the disease does not present. But in an immunocompromised episode, reactivation of the virus can be promoted. This patient probably already had a primary infection and the severity of her disease may have caused her transient immunocompromise that favored the reactivation of the virus and the pulmonary condition.

Another form in which she could have acquired the CMV may have been as a result of the blood transfusions she received. Although it may not be known with certainty, she probably already had contact with the virus. Due to the peculiarity of this case, a literature search was done about this disease. There are reports of isolated cases, even a small series of cases of pneumonias due to CMV in postoperative patients in the ICU. What has begun to be seen and documented is that the state of immunoparalysis, tumor necrosis factor alpha and also the exogenous infusion of catecholamines could, at some point, have reactivated a latent CMV.9

This reactivation does not always translate into a target organ disease, such as in this case where pneumonia developed. One must remember that the lung is the main organ affected with CMV. Although CMV pneumonia is not a disease that we usually take into consideration, we must be conscious of the fact that there are reports that due to the inflammatory response generated by the release of proinflammatory cells, reactivation of the CMV could occur. There are studies in which the viral load of the CMV was monitored by PCR or by antigens and it was observed that there are elevations in the viral load that may be asymptomatic or translated into disease.10-12 Then, given that CMV pneumonia is a very uncommon disease and that there are only a few cases reported in the literature, a universal recommendation cannot be made about initiating management directed against this virus. However, it should be considered in seriously ill patients, such as in this case, when there is an atypical evolution of pneumonia and when broad spectrum antibiotic coverage has been provided for bacteria and yeast and, in spite of this, there is no clinical improvement.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Received 4 December 2013;

accepted 12 December 2013

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:maribellehdez@yahoo.com.mx (M. Hernández Hernández).