Introducción: La bronquiolitis folicular es una lesión pulmonar rara. Consiste en la presencia de abundantes folículos linfoides hiperplásicos con centros germinales reactivos, distribuidos a lo largo de los bronquiolos y compresión de la vía aérea pequeña intratorácica. Existen pocos informes de bronquiolitis folicular en la población pediátrica. Los datos que se conocen de esta enfermedad para esta población han sido extrapolados de estudios realizados en pacientes adultos. El tratamiento se basa en esteroides y, en general, el pronóstico es bueno.

Caso clínico: Describimos el caso de una niña de 5 años de edad, con antecedente de neumonía grave a los 3 años, con adenovirus en el panel viral. Posteriormente, presentó sibilancias recurrentes y tos crónica. En la tomografía axial de tórax de alta resolución se observó un patrón en vidrio despulido, bronquiectasias, atrapamiento aéreo y atelectasia basal derecha, por lo que se realizó una biopsia de pulmón, la cual mostró bronquiolitis folicular linfoidea.

Conclusiones: La bronquiolitis folicular linfoidea es una entidad poco frecuente, que requiere ser sospechada en pacientes con antecedentes de infección por adenovirus. Presenta cuadro clínico de hiperreactividad bronquial y alteraciones radiológicas con patrón en vidrio despulido, bronquiectasias y atrapamiento aéreo. La biopsia pulmonar por toracotomía es la clave para establecer el diagnóstico y el pronóstico.

Background: Follicular bronchiolitis, a rare lung injury, is characterized by abundant hyperplastic lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers distributed along the bronchioles with compression of the lower intrathoracic airway. In the literature there are few reports of follicular bronchiolitis in the pediatric population. Data obtained from this disease have been extracted from studies in adult patients. Treatment is based on steroids with a good prognosis.

Case report: We describe the case of a 5-year-old female with a history of severe pneumonia at 3 years of age, isolating adenovirus in the viral panel. Subsequently, she had recurrent wheezing and chronic cough. High resolution thoracic computed tomography (CT) showed ground glass pattern, bronchiectasis, air trapping and right basal atelectasis. Lung biopsy was performed and reported lymphoid follicular bronchiolitis.

Conclusions: Lymphoid follicular bronchiolitis is a rare entity that requires a high level of suspicion in patients with a history of adenovirus infection, clinical symptoms of bronchial hyperreactivity and radiological changes in ground glass pattern, bronchiectasis and air trapping. Lung biopsy by thoracotomy is the key for diagnosis and prognosis.

Introduction

Follicular bronchiolitis (FB) is the presence of abundant hyperplastic lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers distributed throughout the bronchioles. There are few reports in the literature about FB in the pediatric population, and what is known of the disease has been extrapolated from studies done in adult patients.1

Clinical case

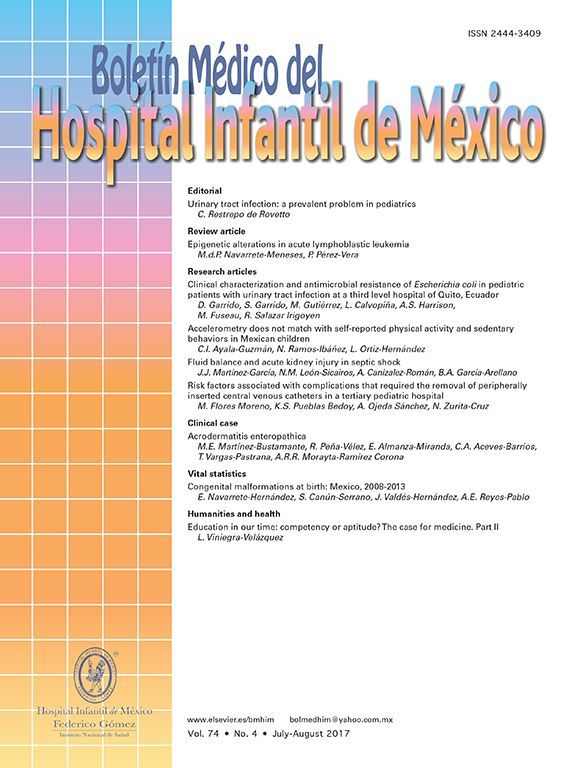

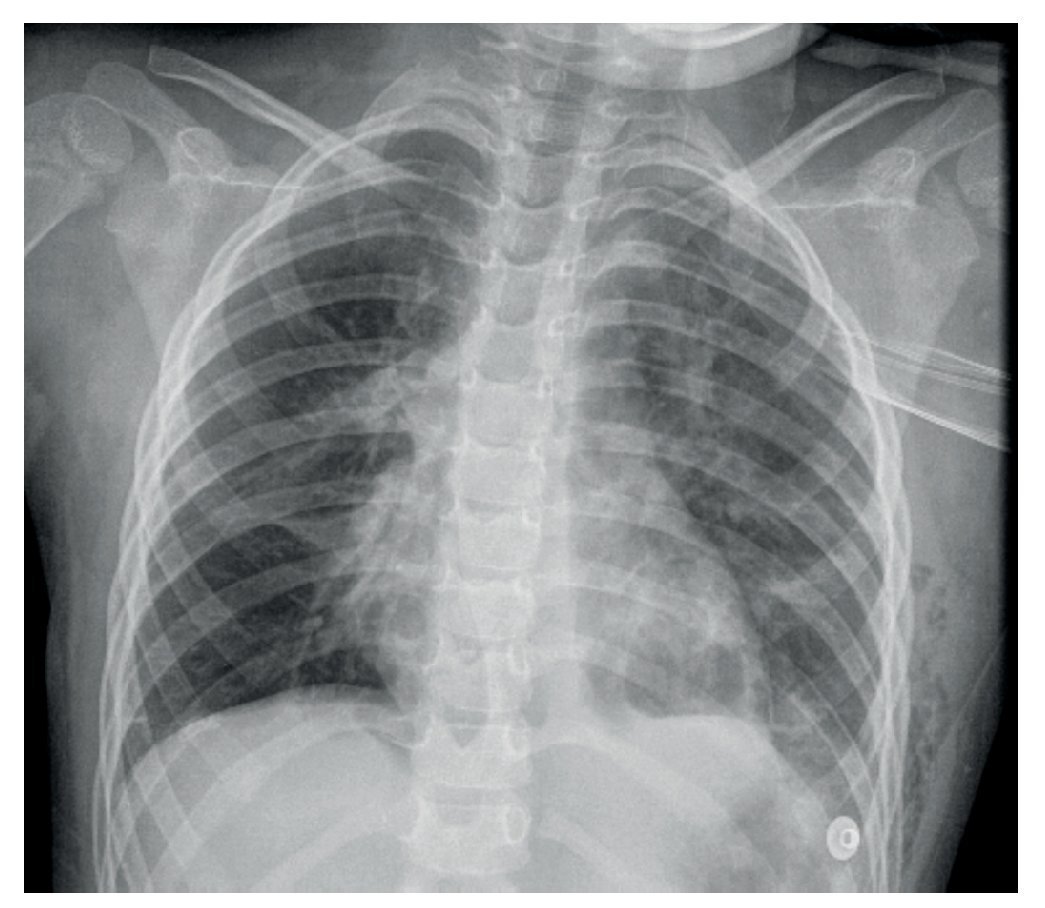

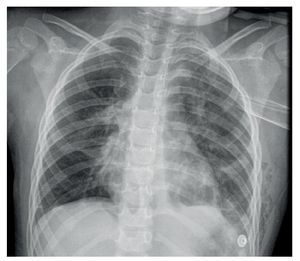

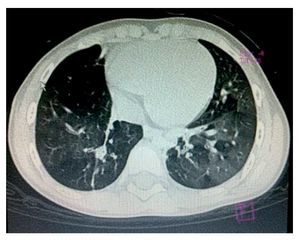

We present the case of a 5-year-old patient with a history of severe pneumonia at the age of 3 years in which infection by adenovirus was documented in the viral panel. The patient presented with right pneumothorax, which was drained with a pleural tube. On physical examination the patient was noted to have mild skin pallor, chest midline, symmetrical, with scar from a right hemithorax, good air entry, and presence of bilateral expiratory wheezes. Chest x-ray noted right basal atelectasis, air trapping and interstitial infiltrate (Fig. 1). In the parenchyma window of the high-resolution chest computed tomography (HRCAT) there was a ground glass pattern, hypodense zones secondary to air entrapment predominantly in the left hemithorax, right posterobasal atelectasis and bilateral basal bronchiectasis (Fig. 2). Spirometry was suggestive of restriction, with FEV1/FVC values 92 (normal), FEV1 63% (low) and FVC 68% (low).

Figure 1 Chest x-ray with right basal atelectasis, air entrapment and bilateral interstitial infiltrate.

Figure 2 High-resolution computed tomography of the chest with ground glass pattern and zones of hypodensity secondary to air entrapment. Right posterobasal atelectasis and bilateral basal bronchiectasis was observed.

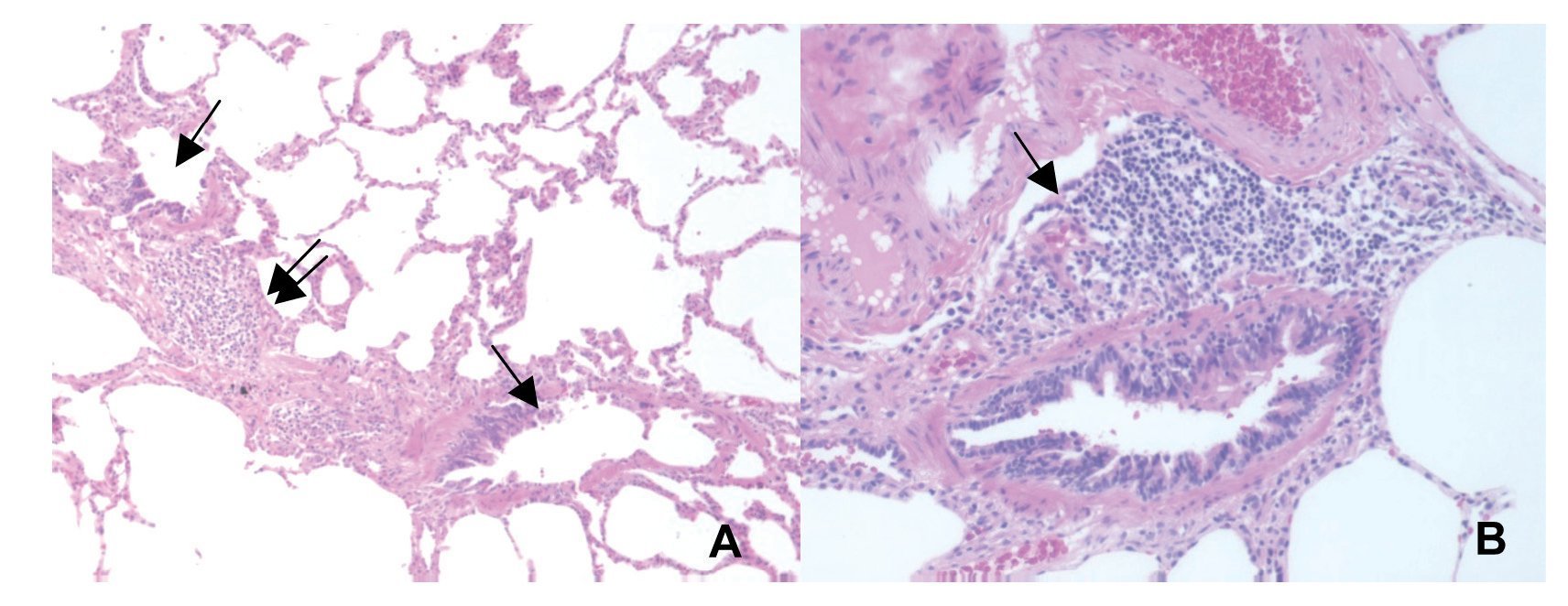

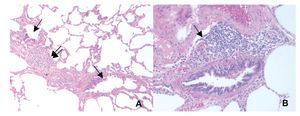

Considering the history of adenovirus infection, clinical and radiological findings, postinfectious bronchiolitis was diagnosed. However, lung biopsy was requested in order to establish the diagnosis and definitive prognosis. Lung biopsy was carried out via a thoracotomy. On histological sections of pulmonary parenchymal fragments, mild focal thickening of the interstitium due to scant mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate was reported. Some showed formation of lymphoid nodules, in addition to dilation and mild edema of the interlobular septum compatible with lymphoid FB (LFB) (Fig. 3). The patient was treated with corticoids and inhaled bronchodilator. There was an adequate treatment response with no wheezes being noted.

Figure 3 (A) Histologically, two membranous bronchioles are seen (arrows) that show partial epithelial denudation and smooth muscle hyperplasia and lymphoid aggregates on the wall of some (double arrows). (B) Approach of a membranous bronchiole with formation of lymphoid follicle in its wall (arrow).

Discussion

LFB is a disease that can present itself at any age. It is characterized by the development of follicular lymphoids and germinal centers of peribronchial or peribronchiolar distribution.1

The majority of cases are associated with infections due to adenovirus, asthma, cystic fibrosis, collagen tissue disease, autoimmune diseases, states of immunodeficiency and systemic hypersensitivity reactions.2 In this case it was secondary to infection due to adenovirus.

An immune response in the face of an antigen with the consequent lymphocytic proliferation is involved in the pathogenesis of LFB. Two stages may be considered in the development of the disease, from symptom onset: 1) the initial exposure to antigens that stimulate the bronchiole-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) and 2) the immunological dysfunction that leads to lymphocytic proliferation.3

The presentation is nonspecific and includes cough, dyspnea, respiratory difficulty, tachypnea and cyanosis. Hemoptysis and growth delay have also been described.

Disease symptoms have been notable because of their initiation during infancy, such as with the present case; however, it may also begin during adolescence.4

For diagnosis, a variety of studies should be done: chest x-rays, HRCAT, pulmonary function tests and lung biopsy with thoracotomy. Immunodeficiencies, autoimmune diseases and infectious diseases could cause FB as a secondary form and should be excluded.5

On chest x-rays, radiological findings characteristic of FB are gradually evident, with bilateral interstitial infiltrate in the subacute phase including alveolar, interstitial or mixed infiltrates as well as consolidation or atelectasis. Radiological imaging may be normal during recovery or also may have an atypical radiological presentation such as bilateral reticulonodular infiltrate, which could be confused with other diseases such as miliary tuberculosis.6

HRCAT of the chest is of great value in the diagnosis of FB. It reveals a parenchyma with nodular opacities <3 mm (although cases >12 mm have been described) and centrilobular or peribronchiolar distribution. Areas of ground glass appearance in bilateral patches of non-segmental distribution, bronchial dilation, thickening of the bronchial wall, thickening of the interlobular septum, peribronchovascular consolidation and bronchiectasis can be seen,2 findings which were present in this patient.

Pulmonary function tests generally reveal an obstructive or restrictive pattern. Normal pulmonary function has also been reported. In this case a restrictive pattern was reported. Despite the presence of clinical, laboratory and radiological findings, the definitive diagnosis requires the performance of a lung biopsy via thoracotomy.4

Histologically there are numerous peribronchial lymphoid follicles. Lymphoid follicles may be located between the bronchioles and pulmonary arteries causing compression of the lumen of the small airways and also can be present along the interlobular septa.6 These findings were described in this case.

Treatment, although not completely defined, is generally directed at the underlying cause once it is recognized. Although patients are treated with bronchodilators and steroids, therapy with macrolides with an alternative focus in some patients has recently been suggested and considered in those patients who are corticosteroid-dependent. Immunosuppressive agents are generally reserved for refractory cases.4 Prognosis of LFB is generally good as patients have a favorable response to therapy with inhaled corticosteroids. However, disease progression has been described when it presents itself at an early age.5

Diagnosis of FB should be considered in patients with history of an adenovirus infection, with a clinical picture of bronchial hyperactivity and radiological changes with ground glass pattern, bronchiectasis and air trapping. The key for establishing the diagnosis and prognosis continues to be lung biopsy via thoracotomy.3

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Received 3 December 2013;

accepted 12 December 2013

* Corresponding author.

E-mail:jessmary04@hotmail.com (J. Sáenz Gómez).