This is the first report on circulating canine rotavirus in Mexico. Fifty samples from dogs with gastroenteritis were analyzed used polymerase chain reaction and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in order to identify parvovirus and rotavirus, respectively; 7% of dogs were infected with rotavirus exclusively, while 14% were co-infected with both rotavirus and parvovirus; clinical signs in co-infected dogs were more severe.

Infectious gastroenteritis are one of the main causes of dog hospitalization, etiological agents identification is a challenge for veterinarians, given that gastroenteritis etiology is caused by diverse pathogenic agents, mainly co-infections among virus or bacteria.1–3

Canine parvovirus (CPV-2) is a member of the Parvoviridae family, belonging to the Protoparvovirus genus and Carnivore Protoparvovirus type 1 species. Diverse reports indicate that is the most diagnosed viral agent in gastroenteritis.4,5 Over the past years, CPV-2 has developed new antigenic variants. In 1980 CPV-2 original strain was replaced by the variant designated type 2a (CPV-2a), in 1984 was identified CPV-2b and in 2001, CPV-2c was detected and reported in Italy. It is possible that CPV-2c is the predominant variant in numerous countries.6

Currently, there is some controversy over clinical characteristics of disease associated with these three variants; however, some authors suggest there are none clinical differences.7

Clinical signs of canine parvovirosis include fever, anorexia, lethargy, depression, vomiting, mucoid to hemorrhagic diarrhea and sometimes leukopenia; however, some reports show parvovirus in dogs with atypical clinical signs, and the authors suggest that this is likely due to CPV-2 evolution.8 On the other hand, the disease can vary depending on the patient; actually, CPV-2c can infect both pups and adults.9

A further factor implicated in variability of clinical profiles in parvovirus is association with other gastroenteric viruses such as canine distemper, canine coronavirus and canine rotavirus.

Actually, rotaviruses are classified as distinct members of the family reoviridae, genus rotavirus, comprising five species (A to E) and two tentative species (F and G). Canine rotavirus is a double-stranded RNA, non-enveloped virus that possesses a segmented genome and that is approximately 60–75nm in diameter; few isolates of rotavirus have been reported in dogs, these have been classified as serotypes G3 and P5A, grouped into group A, rotavirus of this group cause neonatal diarrhea in human and many animal species; it has been demonstrated that direct interspecies transmission between heterologous strains are key mechanisms in generating rotavirus strain diversity in new hosts. Human infection for rotavirus of canine origin has been reported.10,11

Clinical signs of the disease include moderate enteritis, mainly in pups younger than two weeks old,12,13 and it also causes lethargy, anorexia, fever, diarrhea and vomiting. Generally, patients recover within two weeks; however, there are reports of fatal severe enteritis in dogs under two weeks old.14

The presence of antibodies against rotavirus has been demonstrated in a high percentage of adult dogs (80%).15 Rotavirus infection does not have pathognomonic clinical signs and most dogs can be asymptomatic to infection and occasionally signs can be confused with parvovirus, therefore, laboratory test for differential diagnoses are necessary.3,13 In Mexico, it remains unknown whether rotavirus is circulating amongst canine populations and if it plays a primary role as etiologic agent in gastroenteritis.

From March through June 2015, we conducted non-probability sampling in dogs attending the small animal veterinary hospital of the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico (UAEM, by its acronym in Spanish). Fifty dogs of different ages, breeds, non-vaccinated dogs with gastroenteritis signs were selected. One rectal swab was taken from each dog to be used in PCR testing (parvovirus identification), while a second swab was taken for RT-PCR testing (rotavirus identification). Swabs were stored at −80°C until processing.

The Rotateq vaccine (Merck, USA), which contains rotavirus serotypes G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8] and G9P[8], was used as positive control, and in the case of parvovirus the Edo. Mex 1 isolate was used (previously identified in our laboratory and which corresponds to CPV2-c genotype).

In order to extract RNA from rotavirus, each swab was suspended in 200μL of Diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC 1%)-treated water and centrifuged 7min at 5000×g. Supernatant was processed using the GeneJET Viral DNA and RNA Purification kit (Thermoscientific, USA), following manufacturer's instructions.

Rectal swabs used for parvovirus detection were suspended in 500μL of sterile water, centrifuged 1min at 5000×g. 200μL of supernatant was processed for DNA extraction using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

In the case of rotavirus, two-step RT-PCR was performed for each of the samples, using the ImProm-II™ Reverse Transcription System kit (Promega, USA). In the first step, cDNA synthesis was accomplished. 3μL of RNA of each purification plus 2μL (0.5μg/reaction) of primer dT was used in each reaction. All reactions were incubated at 70°C for 15min and subsequently at 4°C for 5min. Next, 1μL of ImProm-II™ Reverse Transcriptase (1u/μL) was added, as well as 1μL dNTP Mix (final concentration 0.5mM each dNTP), 4.6μL MgCl2 (final concentration 1.5mM), 4μL ImProm-II™ 5X Reaction Buffer, 0.5μL Recombinant RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega, USA) (2500Units) and 3.9μL nuclease-free water to reach a final volume of 15μL.

PCR was performed using the primers VP6F (5′-GACGGVGCRACTACATGGT-3′) and VP6R (5′-GTCCAATTCATNCCTGGTGG-3′) designed to amplify a 379bp fragment of VP6 gene (GenBank accession number KJ940164.1); these primers are located in the nucleotides 750–769 and 920–939 respectively. The reaction was performed using 1.5μL of both primers at a 20μmol concentration plus 3μL of cDNA, 5μL of GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega, USA) reaction buffer (pH 8.5) containing 400μM of each nucleotide dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP, 2.5μL of MgCl2 and 0.5μL of taq polymerase. The reaction included 11μL of nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25μL.

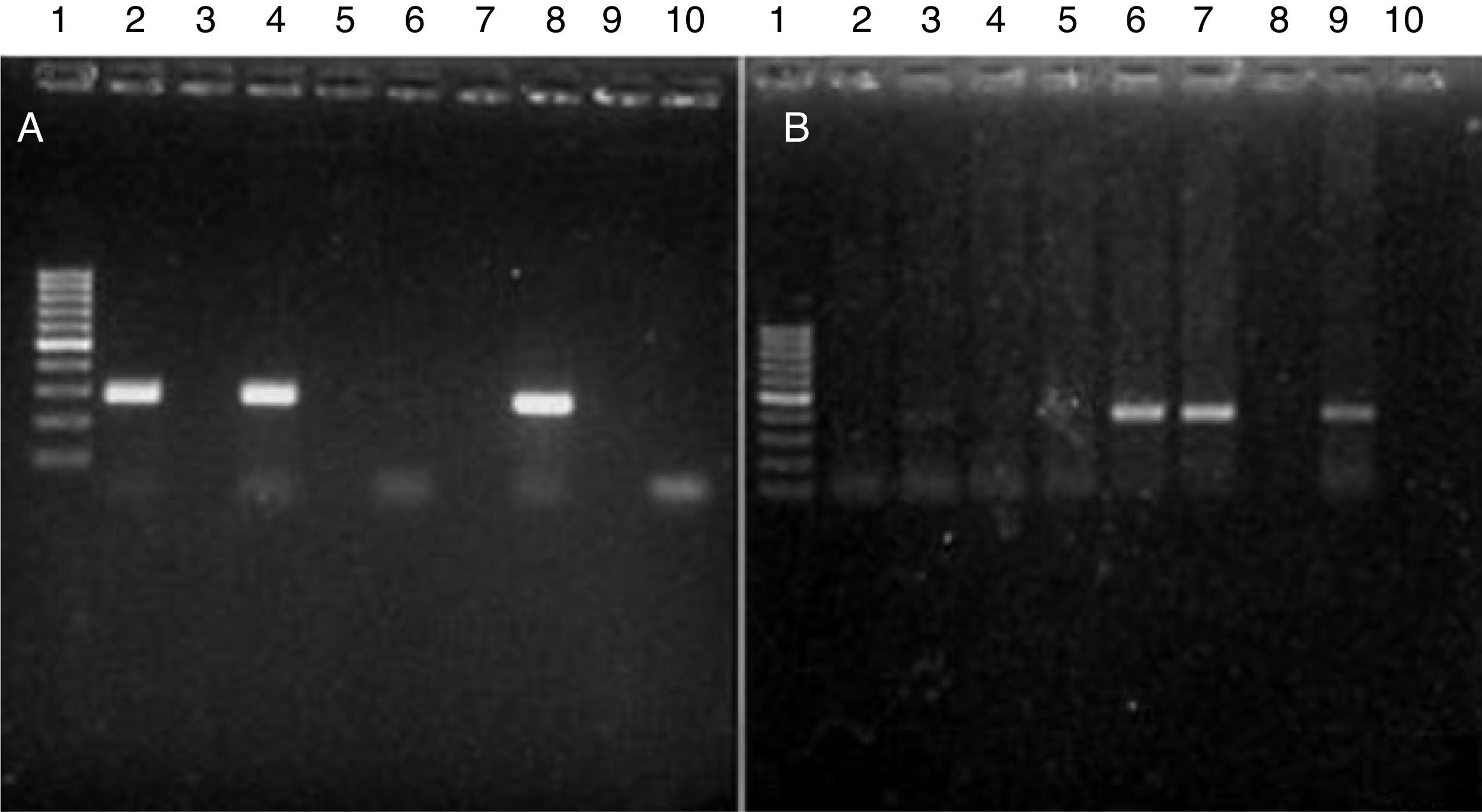

All reactions were performed under the following conditions: 1 cycle at 94°C 5min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C 1min, 61°C 1min, 72°C for 2min and a final extension at 72°C 5min. Amplicons were loaded in a 2.0% agarose gel (stained with 0.5mg/mL of ethidium bromide) and visualized by means of a UV Bio-Imaging Systems Mini Bis Pro transilluminator (Fig. 1).

(A) Parvovirus amplicons. The picture shows a 2.0% agarose gel containing PCR products (275bp) from different samples. Lane 1: DNA length marker (gene ruler 100–1000bp DNA Ladder plus, Fermentas); lanes 2, 4 and 8: CPV-positive samples. Lanes 6 and 10: CPV-negative samples. (B) Rotavirus amplicons (379bp). Lane 1: DNA length marker (gene ruler 100–1000bp DNA Ladder plus, Fermentas); lanes 3, 6, 7 and 9: CRV-positive samples; lanes 2, 4, 5, 8 and 10: CRV-negative samples.

In the case of parvovirus, 100ng of DNA from each sample was used for PCR. Previously, we designed a pair of primers: ParvoInt2FB (5′-TCAAGCAGATGGTGATCCAAG-3′) and ParvoInt2CR (5′-GGTACATTATTTAATGCAGTTA-3′) to amplify a 275bp fragment of the VP2 gene fragment. These primers are located between nucleotides 1107–1130 and 1360–1382 of the gene sequence (GenBank accession number FJ0051962c). Reactions contained 2μL of both primers at a 20μM concentration, plus 12.5μL of GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega, USA) containing the enzyme DNA polymerase, reaction buffer (pH 8.5), 400μM of each nucleotide dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP and 3mM MgCl2. 28.5μL of nuclease-free water was added to obtain a final volume of 50μL.

The following conditions were used in all PCR reactions: one cycle at 94°C for 5min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 52°C for 1min, 72°C for 1min and a final extension at 72°C for 5min. The electrophoresis of amplicons was achieved in a 2% agarose gel (stained with 0.5mg/mL ethidium bromide) and visualized in a UV Bio-Imaging Systems Mini Bis Pro transilluminator (Fig. 1).

In order to verify primer specificity, amplicons from positive controls were sequenced. Sequencing was accomplished through the following procedure: first, PCR products were purified from agarose gel using the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, USA). Next, 30ng of purified PCR product was sequenced by means of the Dye® Terminator v.3.1 Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA). Sequences were processed in a 3100 sequence analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and reaction sequences were analyzed in a PRISM® 3130xl ABI analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA). Due to inconsistencies on the extremes of the obtained sequences, these were edited considering only 250-nucleotide-long final for the alignment, DNA BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was utilized for compared the sequences obtained in this study with sequences available in the GenBank, specifically with GU565078.1 and JX866792.1 for rotavirus and KP682524.1 for parvovirus; sequence alignments analyses were performed with the use of ClustalW method, utilizing BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html).

The sequences obtained were matched 100% with the GenBank sequences (Fig. 2), which indicates that primers used for PCR and RT-PCR in this study, are specific for genome amplification of both viruses. Therefore, the analysis of all samples was accomplished using both PCR and RT-PCR protocols. Out of 50 dogs, 82% (45/50) were positive for at least one of the two viruses, specifically, 60% (27/45) were positive only for parvovirus, 8% (7/45) were positive only for rotavirus and 14% (11/45) were co-infected. Five samples, which were not positive for either parvovirus or rotavirus, were positive for canine distemper or Salmonella spp. (data not shown).

(A) The 250 nucleotides sequenced from the amplified fragments of canine rotavirus samples; sequences obtained were compared with sequences reported in GenBank: GU565078.1, JX866792.1, and EU708927.1. (B) The 250 nucleotides sequenced from the amplified fragments of canine parvovirus samples; sequences obtained were compared with reported sequences in GenBank: KP694306.1, KP694305.1, and KP694304.1.

As a general observation, the clinical signs of rotavirus were milder that those of parvovirus; dogs infected with rotavirus exclusively, displayed abdominal pain, lethargy, vomiting, mucoid diarrhea and in some cases leukocytosis. However, in the co-infected dogs severe gastroenteric symptoms were observed in addition to leukopenia, panleukopenia, mucoid or hemorrhagic diarrhea, vomiting and lethargy. These symptoms were even more severe that those observed in dogs infected with only parvovirus (Table 1).

Clinical signs and hematologic findings in dogs infected with canine parvovirus (CPV-2), dogs infected with canine rotavirus (CRV) and co-infected (parvovirus–rotavirus) dogs with gastroenteritis.

| Clinical findings/type of infection | % with CPV (n=27) | % with CRV (n=7) | % with CPV–CRV (n=11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 66.6 | 28.5 | 81.8 |

| Anorexia | 33.3 | 0 | 72.7 |

| Lethargy | 81.4 | 14.2 | 100 |

| Vomiting | 44.4 | 14.2 | 54.5 |

| Fever (>39.5°C) | 14.8 | 0 | 36.3 |

| Hemorrhagic diarrhea | 70.3 | 14.2 | 90.9 |

| Mucoid diarrhea | 29.6 | 85.7 | 9.0 |

| Leukocytosis | 0 | 28.5 | 18.1 |

| Leukopenia | 40.7 | 0 | 54.5 |

| Panleukopenia | 14.8 | 0 | 36.3 |

Clinical signs, physical examination, and laboratory test results in dogs with viral enteritis. Reference ranges for total leukocyte count: 6.0–17.0×109/L, panleukopenia refers to general low counts of all leukocyte count.

Data from the present study were compared to previous studies, and our results show a relatively high percentage of dogs with co-infection (14%) in relation to findings in other countries, for instance 2.4% has been reported in U.S.A., as inferred from reverse passive hemagglutination (RPHA), in Japan, 1.2% was estimated from viral isolation and 2% using electron microscopy, while in Italy there were no identifications using PAGE.1,2,4 These low percentages might be related to the techniques employed in these studies, in this sense, in the present study RT-PCR was used which has demonstrated a higher sensitivity.16 It is also possible that contrasting results are influenced by the country where studies were conducted, as it is well documented that different rotavirus genotypes are associated with low-income areas. Furthermore, other studies have reported the presence of rotavirus only in pups less than two months of age or newborns,11 however, in this study rotavirus infection was detected in dogs older than 6 months.

This report is the first study demonstrating the presence of circulating rotavirus in dogs from the State of Mexico. Although rotavirus is of little importance for veterinarians as it has low mortality rate, in the present study it was observed to play an important role in severity of viral gastroenteritis, especially when associated to canine parvovirus. On the other hand, although parvovirus is considered the most important pathogen in canine gastroenteritis, rotavirus is of special interest to public health due to its zoonotic potential. In support of this, there exist reports of inter-species transmission of canine rotavirus of the G3 group to children in Italy and Taiwan.10

Although this is the first report of rotavirus in canines of the State of Mexico, future molecular epidemiology studies should be conducted to identify the circulating genotypes in dog populations throughout Mexico, as this will increase our understanding on the importance of rotavirus in dogs.

Financial supportThe authors would like to thank to the Fundación Educación Superior-Empresa, A.C. for the financial support.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ariadna Flores thank to Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología for the scholarship awarded for postgraduated studies in Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Programa de Maestria y Doctorado en Ciencias Agropecuarias y Recursos Naturales.