The various types of lignocellulosic biomass found in plants comprise the most abundant renewable bioresources on Earth. In this study, the ruminal microbial ecosystem of black goats was explored because of their strong ability to digest lignocellulosic forage. A metagenomic fosmid library containing 115,200 clones was prepared from the black-goat rumen and screened for a novel cellulolytic enzyme. The KG35 gene, containing a novel glycosyl hydrolase family 5 cellulase domain, was isolated and functionally characterized. The novel glycosyl hydrolase family 5 cellulase gene is composed of a 963-bp open reading frame encoding a protein of 320 amino acid residues (35.1kDa). The deduced amino acid sequence showed the highest sequence identity (58%) for sequences from the glycosyl hydrolase family 5 cellulases. The novel glycosyl hydrolase family 5 cellulase gene was overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Substrate specificity analysis revealed that this recombinant glycosyl hydrolase family 5 cellulase functions as an endo-β-1,4-glucanase. The recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase showed optimal activity within the range of 30–50°C at a pH of 6–7. The thermostability was retained and the pH was stable in the range of 30–50°C at a pH of 5–7.

Cellulose is a major polysaccharide compound in the plant cell wall and is composed of repeating cellobiose units linked via β-1,4-glycosidic bonds. It is one of the most abundant renewable bioresources in nature.1 The enzyme cellulase can be categorized into three major classes based on its catalytic action: endo-β-1,4-glucanases (EC 3.2.1.4), cellobiohydrolases (EC 3.2.1.91), or β-glucosidases (EC 3.2.1.21). Endo-β-1,4-glucanases randomly attack internal amorphous sites in cellulose polymers, generating new chain ends. Cellobiohydrolases remove cellobiose from reducing or non-reducing ends of cellulose polymers. β-Glucosidases hydrolyze cellodextrins and cellobioses to glucoses.2 Cellulases have generated commercial interest in various sectors, including the food, energy, pulp, and textile industries.3 Among the three types of cellulases, endo-β-1,4-glucanase can release smaller cellulose fragments of random length.4 Consequently, endo-β-1,4-glucanase has a biotechnological potential in various industrial applications. This enzyme has been industrially applied in biomass waste management, pulp and paper deinking, and textile biopolishing.5 In addition, this enzyme can be practically used to produce better animal feeds, improve beer brewing, decrease the viscosity of β-glucan solutions, and improve biofinishing in the textile industry.5

Cellulases can be produced using a wide range of microorganisms, plants, and animals. Symbiotic microorganisms in the rumen of herbivores can hydrolyze and ferment cellulosic polymers, thereby allowing the host to obtain energy from the indigestible polymers.6 Therefore, rumen microbial communities in ruminants are attractive sources of cellulases because these communities have adapted to utilization of lignocellulosic plant biomass.6–9

Although the ruminal microbial ecosystem is highly diverse, the majority of rumen microorganisms are unculturable.6 It is estimated that less than 1% of microbial species in nature have ever been cultured.10 A culture-independent method has been developed to overcome this problem. This approach involves isolating metagenomic DNA from the environment and cloning this DNA into a vector to generate a metagenomic library. The library is subsequently screened for genes of interest via the detection of genotypic or phenotypic biomarkers using DNA–DNA hybridization, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or enzymatic assay techniques.11

The Korean black goat is a grazing herbivore with a dietary preference for herbaceous and woody dicots, such as forbs, shrub leaves, and stems.12 Black goats are classified as small ruminants, and their foregut digestion allows feed particles to move more rapidly through the alimentary tract, promoting higher herb intake in comparison with other larger herbivores.13 Therefore, the objectives of this study were to isolate and functionally characterize a novel cellulase metagenomically derived from the rumen contents of black goats.

Materials and methodsConstruction and functional screening of a metagenomic fosmid libraryAll animal studies and standard operating procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the National Institute of Animal Science, Rural Development Administration, Suwon, Korea (No. 2009-007, D-grade, surgery). Three 18-month-old Korean black goats were raised at the National Institute of Animal Science and were freely fed rice straw and mineral supplements 30d prior to the experiment to maximize cellulolytic adaptation of microorganisms in their rumens. Rumen contents of the three black goats were collected immediately after slaughter. Metagenomic DNA was extracted from the contents using hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide and sodium dodecyl sulfate (CTAB-SDS).14 DNA fragments ranging from 10 to 50kb were obtained by partial digestion with the restriction enzyme HindIII to construct a metagenomic fosmid library by means of the CopyControl™ Fosmid Library Construction Kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI). The technique was based on the pCC1FOS vector, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Escherichia coli DH5α™ (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) transformants, carrying various recombinant fosmids, were transferred to 384 well plates. To determine an average insert size of the fosmid library, a total of 36 clones were randomly selected and digested with the restriction enzyme NotI.

A fraction of the library was spread on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (15μg/mL) and 0.2% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), which is a substrate for screening for endo-β-1,4-glucanase activity. After incubated and stained as described previously,15 fosmid clones with cellulolytic activity were detected upon the formation of clear zones around the colonies. Activity-based metagenomic screening yielded a single fosmid clone (Ad125D08) that formed one of the largest clear zones.

Shotgun sequencing of the enzyme-positive fosmid cloneShotgun sequencing and molecular analyses were performed to localize the cellulase gene within the enzyme-positive fosmid clone and to subclone the gene for effective biochemical characterization. Bacteria carrying the cellulolytic fosmid clone (Ad125D08) were cultured in 100mL of the LB medium containing 25μg/mL of chloramphenicol at 37°C for 20h. After the cells were harvested, the DNA was extracted using a Qiagen Plasmid Midi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and subjected to shotgun sequencing that comprised two approaches: conventional Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing. For shotgun sequencing with Sanger methodology, 15μg of DNA from the cellulolytic fosmid clone was randomly fragmented into sections measuring 2–3kb in size. Fragmentation was performed using the HydroShear DNA shearing device (Genomic Solution, Waltham, MA) under the following processing conditions: sample volume 200μL, speed code 11, and 20 shearing cycles. Small fragments were removed and were subsequently repaired with DNA polymerase and the polynucleotide kinase method (BKL Kit; TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). The prepared DNA fragments were ligated into the SmaI site of pUC19. The ligation products were introduced into E. coli DH10B cells by electroporation. Approximately 192 recombinant plasmids in the shotgun DNA library were randomly selected for sequencing. Each plasmid DNA was bidirectionally sequenced as described previously.16 The sequencing data was assembled using Phred and Phrap software (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). One pyrosequencing run was conducted on GS Junior sequencing system (Roche Diagnostics, Oakland, CA) as described previously.17 The pyrosequencing data were assembled using GS De Novo Assembler, version 2.7.

In silico sequence analyses of the enzyme-positive fosmid cloneAll contigs from conventional shotgun sequencing with Sanger methodology and from the pyrosequencing assembly were combined to construct a full metagenomic-insert-DNA sequence using the SeqMan software in Lasergene version 7 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). Gene prediction in each contig was performed using MetaGeneMark with default parameters.18 Functional annotation was performed by searching Pfam domains on the Pfam website (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk).19 Amino acid sequences were deduced from the nucleotide sequences of the enzyme-positive fosmid clone (Ad125D08) and were analyzed using BlastP on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database to search for proteins with similarity to the amino acid sequences derived from the identified open reading frames (ORFs). Multiple alignments among amino acid sequences were deduced from the ORFs, and the sequences of other proteins were performed using ClustalW software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). The PROSITE database was used to predict the module structures and signature sequences of the enzyme (http://prosite.expasy.org/). The N-terminal regions were analyzed using Signal IP software for a signal peptide sequence (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) and by HMMTOP 2.0 software for transmembrane regions (http://www.enzim.hu/hmmtop/html/submit.html).

Heterologous expression and purification of the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanaseThe KG35 gene (the complete ORF of the putative cellulase gene) was amplified from the enzyme-positive fosmid clone (Ad125D08) by PCR. The amplicon was ligated into the expression vector pET24 (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany), and the resulting recombinant vector was introduced into E. coli Rosetta-gami™ (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). Additional screening for cellulolytic activity of the enzyme produced by the transformed E. coli cells was performed using the same CMC agar plate method as described previously.15 The cellulolytic E. coli cells were grown at 37°C and the transgene expression was induced with 0.2mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) as described previously.7 After incubation for 6h at 26°C, the cells were harvested and disrupted by sonication as described previously.9 The overexpressed protein was purified from the resulting cell-free extracts using the Chelating Excellose® Spin Kit (Bioprogen, Daejeon, South Korea). A 2.0-μL aliquot of the purified protein was inoculated into the CMC agar plates to confirm the enzymatic activity. The proteins were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), according to Laemmli (1970),20 and the protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Zymogram analysis of the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase was performed using a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% CMC under denaturing conditions as described previously.21

Enzymatic characterization of the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanaseSpecific activities of the purified recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase toward various substrates were evaluated under the following standard conditions. The substrates used in this study were CMC, barley glucan, laminarin, avicel, xylan from birchwood, β-mannan, p-nitrophenyl-d-glucopyranoside, and p-nitrophenyl-d-cellobioside. In all the assays, 10μL of a properly diluted enzyme solution were added to 200μL of 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7), containing 1% (w/v) of each substrate. The enzymatic reactions were allowed to proceed at 50°C (different reaction duration): 15min for CMC, glucan, laminarin, and avicel; 10min for xylan from birchwood and β-mannan; and 20min for p-nitrophenyl-d-glucopyranoside and p-nitrophenyl-d-cellobioside. Specific activity was defined as the number of activity units per milligram of protein. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to release 1μmol of reducing sugar per minute. Additionally, 1 unit of enzymatic activity producing chromogenic sugar derivatives (p-nitrophenyl-d-glucopyranoside and p-nitrophenyl-d-cellobioside) as the substrates was defined as the amount of the enzyme required to release 1μmol of p-nitrophenol per minute. The amounts of released reducing sugar and p-nitrophenol were determined by measuring the absorbances at 540 or 400nm, respectively. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Optimal pH was determined by assaying the enzymatic activity of the purified recombinant, KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase, at 50°C for 15min at pH ranging from 4 to 10. To determine the optimal temperature, enzymatic activity was analyzed in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) for 15min at a temperature ranging from 20 to 70°C. All assays were performed in triplicate. The pH stability was assessed after the enzyme was pre-incubated at 4°C for 24h at pH ranging from 4 to 10. The thermal stability was assessed after the enzyme was pre-incubated for 1h in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) at various temperatures mentioned above. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Nucleotide sequence accession numberThe nucleotide sequence of the enzyme-positive fosmid clone (Ad125D08), including the complete ORF of the KG35 gene (a novel GH5 cellulase gene), was deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number KJ631389.

ResultsConstruction and functional screening of the metagenomic fosmid libraryA metagenomic fosmid library containing 115,200 clones was constructed from the rumen microorganisms of black goats. NotI restriction enzyme analyses revealed that the average insert size was typically 31kb (data not shown). A total of 155 independent fosmid clones, displaying carboxymethyl cellulase (CMCase) activity, were identified. Among them, a single fosmid clone (Ad125D08) formed one of the largest clear zones on the CMC-containing screening plates and was selected for further analysis.

Conventional shotgun sequencing with the Sanger method was performed under 2.7-fold coverage, and ∼300kb of pyrosequencing reads were produced. Consequently, one contig of 42.453kb was obtained without the pCC1FOS vector sequence. Thirty-four ORFs were predicted in the contig sequence of fosmid clone Ad125D08, and an ORF containing a cellulase domain (KG35 gene) was identified and localized within the clone.

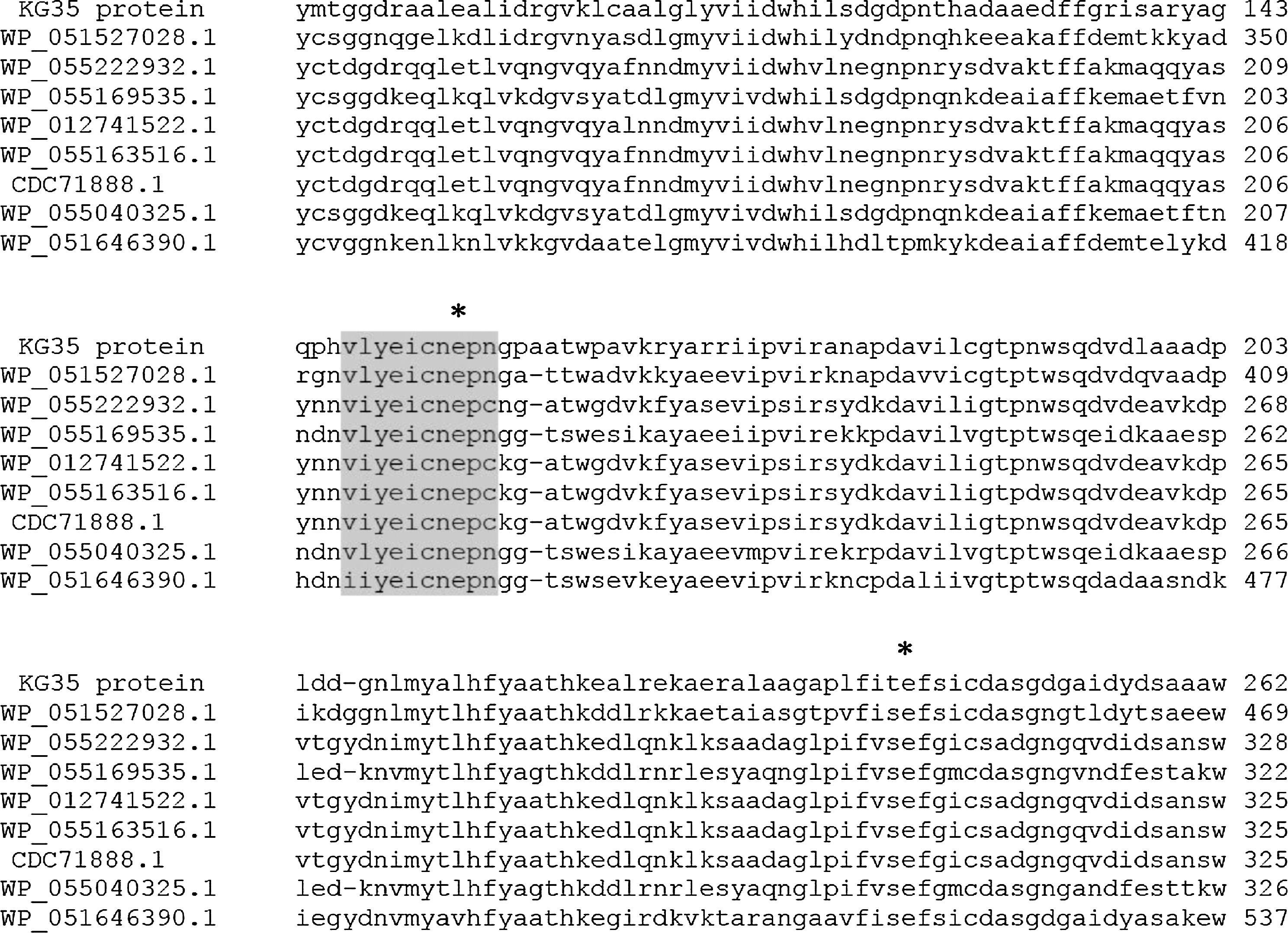

In silico sequence analysis of the putative KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanaseSequence analysis of the putative KG35 gene revealed a single ORF of 963bp encoding a polypeptide of 320 amino acid residues, with an estimated molecular mass of 35.1kDa and pI of 5. Signal IP and HMMTOP 2.0 software programs could not detect any known signal peptide sequence or transmembrane region in the KG35 protein. The module structure search in the PROSITE database predicted that the KG35 protein contains a GH5 cellulase catalytic domain with a conserved (amino acid) signature sequence VLYEICNEPN, and its second Glu residue was assumed to play a catalytic role (Fig. 1).22,23

Multiple alignment of the KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase GH5 domain with other homologous GH5 protein domains. The deduced amino acid sequence of a GH5 family domain in KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase was aligned with those of selected homologous enzymes from the following microorganisms: Eubacterium cellulosolvens (WP_051527028.1); Agathobacter rectalis (WP_055222932.1); Roseburia inulinivorans (WP_055169535.1); A. rectalis (WP_012741522.1); Ruminococcus torques (WP_055163516.1); Eubacterium rectale CAG:36 (CDC71888.1); R. inulinivorans (WP_055040325.1); and Lachnospiraceae bacterium C6A11 (WP_051646390.1). Signature sequences of GH5 domains are shaded in gray. The Glu residues under the star symbols indicate the catalytic sites.

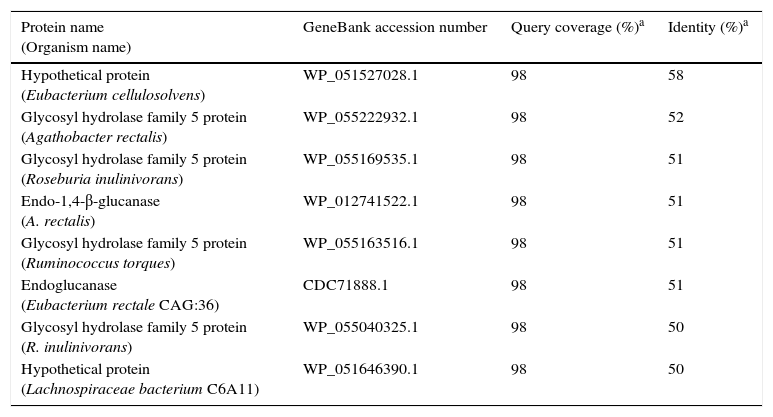

A BlastP search, comparing the amino acid sequence of the KG35 protein with those of other proteins registered in the GenBank database, revealed that this protein has the closest (58%) sequence identity to a hypothetical protein from Eubacterium cellulosolvens (WP_051527028.1) and shares even less sequence identity with other GH5 family protein homologs from various microbial species (Table 1). The amino acid sequences of these homologous proteins possess characteristic features conserved among the GH5 family of enzymes (Fig. 1).

Amino acid sequence identity between the novel KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase and other (Homologous) proteins.

| Protein name (Organism name) | GeneBank accession number | Query coverage (%)a | Identity (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothetical protein (Eubacterium cellulosolvens) | WP_051527028.1 | 98 | 58 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 5 protein (Agathobacter rectalis) | WP_055222932.1 | 98 | 52 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 5 protein (Roseburia inulinivorans) | WP_055169535.1 | 98 | 51 |

| Endo-1,4-β-glucanase (A. rectalis) | WP_012741522.1 | 98 | 51 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 5 protein (Ruminococcus torques) | WP_055163516.1 | 98 | 51 |

| Endoglucanase (Eubacterium rectale CAG:36) | CDC71888.1 | 98 | 51 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 5 protein (R. inulinivorans) | WP_055040325.1 | 98 | 50 |

| Hypothetical protein (Lachnospiraceae bacterium C6A11) | WP_051646390.1 | 98 | 50 |

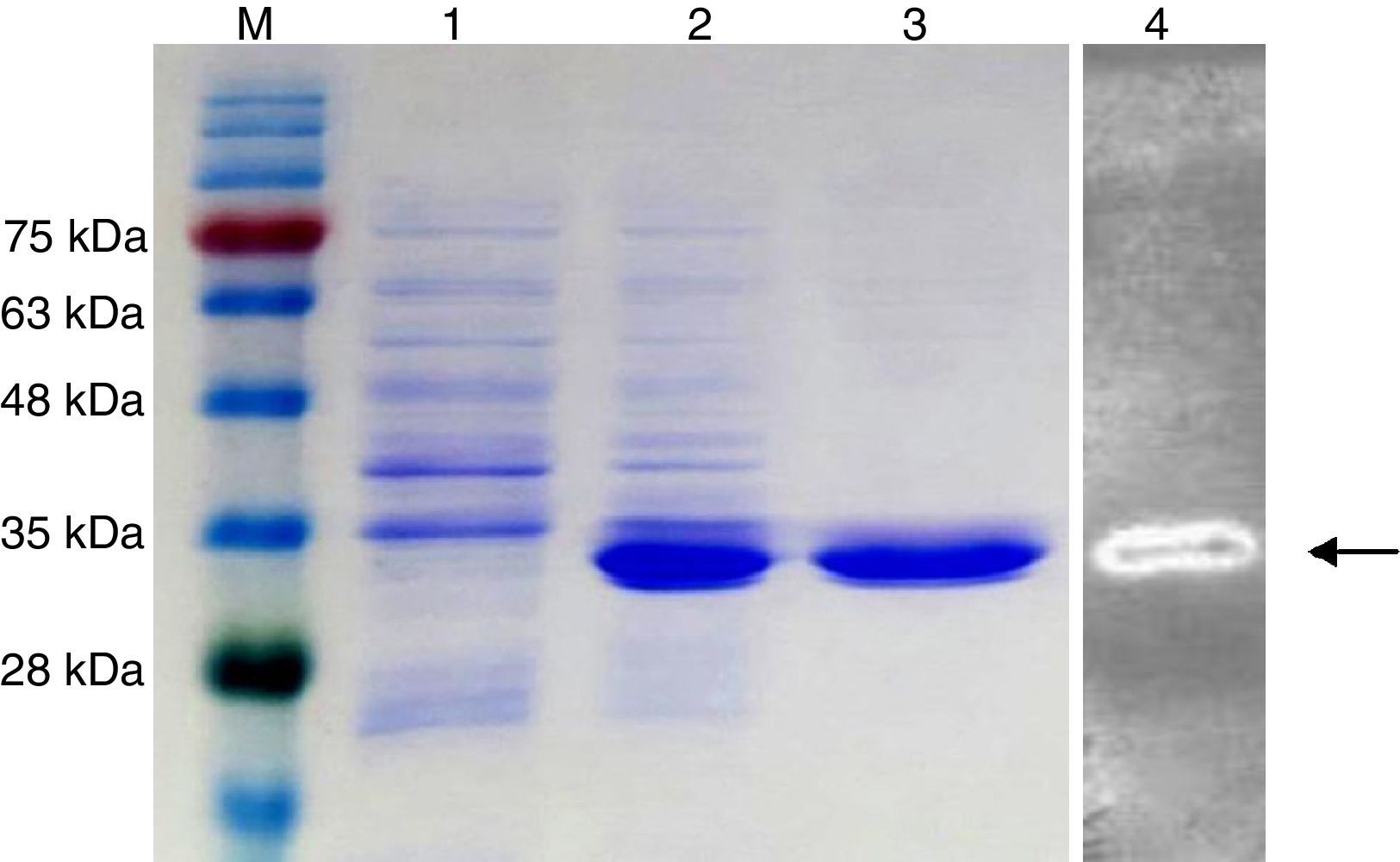

The putative endo-β-1,4-glucanase gene (KG35) was cloned and overexpressed in E. coli and the resulting recombinant enzyme was purified, as described in the materials and methods section. SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase showed a single band on the gel, with the apparent molecular mass of approximately 35kDa (Fig. 2). Zymogram analysis revealed a single band corresponding to an active endo-β-1,4-glucanase of the same molecular mass as the band (Fig. 2).

SDS-PAGE analyses of recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase produced in E. coli Rosetta-gami™. Lane M: protein molecular weight markers; lane 1: total cell-free extracts before induction; lane 2: the soluble fraction after the induction; lane 3: purified KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase; lane 4: zymogram analysis of KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase.

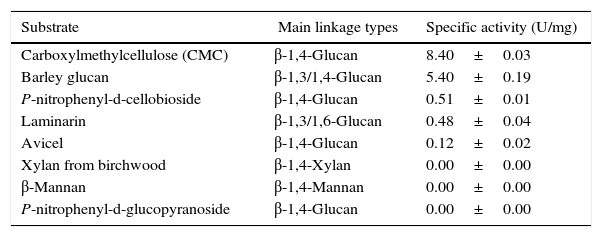

Substrate specificity toward various substrates was determined (Table 2). The endo-β-1,4-glucanase showed strong specific activities toward CMC (8.40U/mg) and barley glucan (5.40U/mg). In contrast, this enzyme showed only trace enzymatic activity toward laminarin (0.48U/mg), p-nitrophenyl-d-cellobioside (0.51U/mg), and avicel (0.12U/mg). In addition, the endo-β-1,4-glucanase could not hydrolyze p-nitrophenyl-d-glucopyranoside, xylan from birchwood, or β-mannan.

Substrate specificity of the novel KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase toward various substrates.

| Substrate | Main linkage types | Specific activity (U/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxylmethylcellulose (CMC) | β-1,4-Glucan | 8.40±0.03 |

| Barley glucan | β-1,3/1,4-Glucan | 5.40±0.19 |

| P-nitrophenyl-d-cellobioside | β-1,4-Glucan | 0.51±0.01 |

| Laminarin | β-1,3/1,6-Glucan | 0.48±0.04 |

| Avicel | β-1,4-Glucan | 0.12±0.02 |

| Xylan from birchwood | β-1,4-Xylan | 0.00±0.00 |

| β-Mannan | β-1,4-Mannan | 0.00±0.00 |

| P-nitrophenyl-d-glucopyranoside | β-1,4-Glucan | 0.00±0.00 |

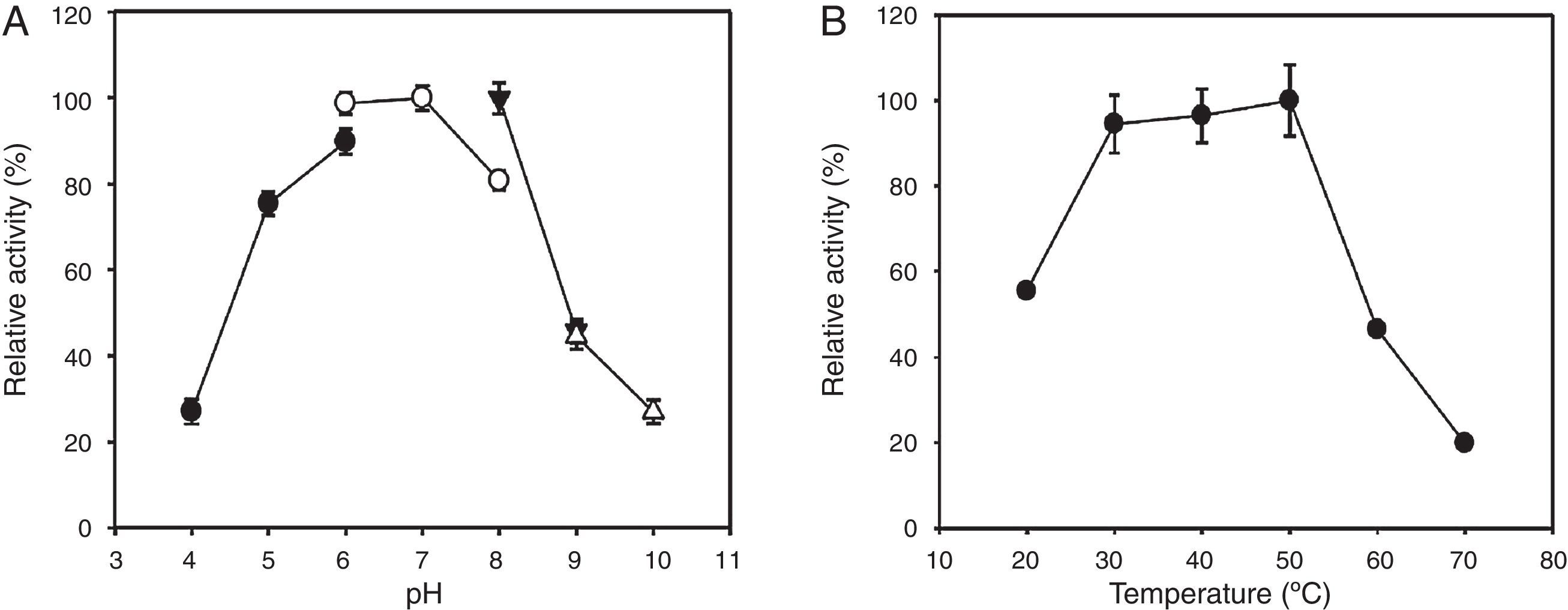

The optimal pH and temperature of the recombinant enzyme were determined under various pH and temperature conditions (Fig. 3). The optimal pH and temperature of the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase toward CMC was approximately 6–7 and 30–50°C, respectively.

Effects of pH and temperature on the activity of recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase. (A) The optimal enzyme activity was measured at a pH range of 4–10. The buffers were 0.1M sodium acetate (pH 4–6, ●), 0.1M sodium phosphate (pH 6–8, ○), 0.1M Tris–HCl (pH 8–9, ▾), and 0.1M glycine–NaOH (pH 9–10, ▵). (B) The optimal enzyme activity was measured at a temperature range of 20–70°C. The error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate measurements.

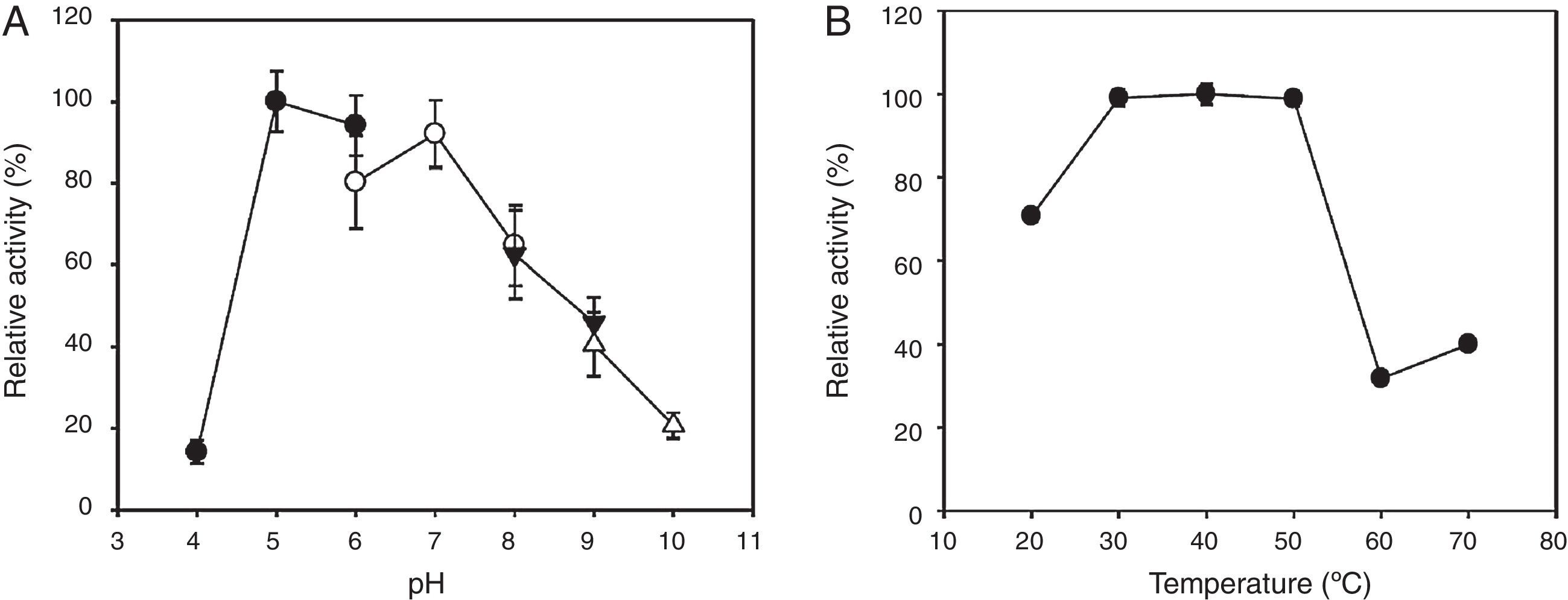

In addition, the enzymatic stability was tested under various pH and temperature conditions (Fig. 4). The endo-β-1,4-glucanase retained more than 70% of activity after 24h of incubation at pH 5–7. The same enzyme showed thermostability after a 1-h incubation at 30–50°C; however, it declined in activity by greater than 60% after a 1-h incubation above 50°C. Our empirical data collectively indicates that the recombinant enzyme retained its pH and temperature stability approximately within its optimal pH and temperature ranges, respectively.

Effects of pH and temperature on the stability of the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase. (A) The pH stability as determined by measuring the residual activity after the enzyme was preincubated at 4°C for 24h at the indicated pH levels from 4 to 10. The buffers were 0.1M sodium acetate (pH 4–6, ●), 0.1M sodium phosphate (pH 6–8, ○), 0.1M Tris–HCl (pH 8–9, ▾), and 0.1M glycine–NaOH (pH 9–10, ▵). (B) The temperature stability as determined by measuring the residual activity after the enzyme was pre-incubated at pH 7 for 1h over the temperature range of 20–70°C. The error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate measurements.

It has been reported that the GH5 family of cellulases contain the conserved amino acid signature sequence pattern: [LIV]-[LIVMFYWGA](2)-[DNEQG]-[LIVMGST]-{SENR}-N-E-[PV]-[RHDNSTLIVFY].24 The conserved signature sequence of the KG35 protein could be located in the above-mentioned GH5 family signature sequence pattern. This result indicated that the KG35 protein exhibited a strong relation to the GH5 family of cellulases. Furthermore, the KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase protein exhibited the closest (58%) amino acid sequence similarity to its GH5 homologous enzymes, implying that the KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase protein has never been identified or characterized, thus is a novel amino acid sequence.

The CMC and barley glucan, which are primarily based on β-1,4-glycosidic bonds and have amorphous structures, were found to be the most favorable substrates for the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase. Amorphous laminarin, containing β-1,3/1,6-glycosidic bonds, and hemicelluloses, including xylan from birchwood and β-mannan, were not specific substrates of the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase. Although avicel mostly contains β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, it was not efficiently hydrolyzed by this enzyme. Avicel contains β-1,4-glycosidic bonds akin to other soluble cellulosic substrates, and its crystalline structure can undergo efficient hydrolysis when a cellulose-binding domain is involved in the hydrolysis reaction.25,26 Nevertheless, sequence analysis could not detect any cellulose-binding domain in the KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase; therefore the absence of this domain may explain the weak enzymatic activity toward avicel. Two synthetic substrates used in this study, p-nitrophenyl-d-cellobioside and p-nitrophenyl-d-glucopyranoside, are synthetic substrates for exoglucanase and β-glucosidase, respectively.27,28 Therefore, the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase exerted slight exoglucanase activity and no β-glucosidase activity, respectively. All of these results pertaining to substrate specificity indicate that KG35 cellulase is most likely to hydrolyze the β-1,4-glycosidic bonds of the amorphous regions of cellulose and consequently function as an endo-β-1,4-glucanase.

The recombinant KG35 cellulase was maximally active and enzymatically stable at a pH range of 6–7 and at a temperature range of 30–50°C. The optimum and stability characteristics of the recombinant enzyme were similar to those of other cellulose enzymes from rumenal microorganisms of other ruminants. Other cellulases from rumenal microorganisms of the cow were reported to have the optimal pH range of 5–7 and an optimal temperature of approximately 50°C.9,29,30 The cellulase from rumen-resident bacteria was reported to retain 70% of its activity in the pH range from 5 to 7 and in a temperature range from 30 to 50°C.30

The ruminal pH of small ruminants ranges from 5 to 7, under normal dietary conditions, and the ruminal temperature can vary from 38 to 41°C.31 The cellulolytic reactions of ruminal-bacteria cellulase have been reported to be relatively more resistant at the pH of 6.5–7 in culture, but the reactions were weakened as the culture pH decreased.32 KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase may be well-adapted to the ruminal environments of black goats because the pH and temperature conditions under which the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase showed relatively higher activity and stability were in agreement with the ruminal pH and temperature conditions that occurs naturally in ruminants, including goats. The above observation can explain why the recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase functions better at mildly acidic/neutral pH and a moderate temperature than at an acidic/alkaline pH or strongly unphysiological temperature.

Cellulase can effectively convert cellulose, an anti-nutritional component, in animal feedstocks into its hydrolysates, nutritive ingredients, yielding improved performance of animals.5 Therefore, applications of different cellulases from various sources have attracted considerable attentions in the feed industry. KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase may be exploited as a feed additive to improve feed utilization of ruminants, because the enzyme may be well-adapted to the ruminal environments. Moreover, the enzyme can be potentially used to make cellulosic ethanol, second generation biofuel, from cellulosic feedstocks such as grass, wood, and crop residues.

This study presents novel results pertaining to the construction and screening of a metagenomic library from the rumenal microorganisms of black goats for identification and characterization of a novel cellulolytic enzyme. A total of 155 cellulolytic fosmid clones were selected from the metagenomic library. Among them, the KG35 gene was successfully isolated as a clone with the strongest cellulose-degrading activity. The KG35 gene was found to encode a novel member of the GH5 family of cellulases, and this novel gene was efficiently translated and overexpressed in E. coli Rosetta-gami™. Substrate specificity analysis revealed that the recombinant KG35 cellulase functions as an endo-β-1,4-glucanase. The recombinant KG35 endo-β-1,4-glucanase optimally functions in the pH range of 6–7 and temperature range of 30–50°C. The endo-β-1,4-glucanase retained enzymatic stability in the pH range of 5–7 and the temperature range of 30–50°C.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Programs for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (Project Nos. PJ006649, PJ008701 and PJ011163)”, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. J.-S. Lee (for in silico experiment design) and K.-S. Kim (for other experiment design) are co-corresponding authors of this work.