Lectins are non-immunogenic carbohydrate-recognizing proteins that bind to glycoproteins, glycolipids, or polysaccharides with high affinity and exhibit remarkable ability to agglutinate erythrocytes and other cells. In the present study, ten Fusarium species previously not explored for lectins were screened for the presence of lectin activity. Mycelial extracts of F. fujikuroi, F. beomiformii, F. begoniae, F. nisikadoi, F. anthophilum, F. incarnatum, and F. tabacinum manifested agglutination of rabbit erythrocytes. Neuraminidase treatment of rabbit erythrocytes increased lectin titers of F. nisikadoi and F. tabacinum extracts, whereas the protease treatment resulted in a significant decline in agglutination by most of the lectins. Results of hapten inhibition studies demonstrated unique carbohydrate specificity of Fusarium lectins toward O-acetyl sialic acids. Activity of the majority of Fusarium lectins exhibited binding affinity to d-ribose, l-fucose, d-glucose, l-arabinose, d-mannitol, d-galactosamine hydrochloride, d-galacturonic acid, N-acetyl-d-galactosamine, N-acetyl-neuraminic acid, 2-deoxy-d-ribose, fetuin, asialofetuin, and bovine submaxillary mucin. Melibiose and N-glycolyl neuraminic acid did not inhibit the activity of any of the Fusarium lectins. Mycelial extracts of F. begoniae, F. nisikadoi, F. anthophilum, and F. incarnatum interacted with most of the carbohydrates tested. F. fujikuroi and F. anthophilum extracts displayed strong interaction with starch. The expression of lectin activity as a function of culture age was investigated. Most species displayed lectin activity on the 7th day of cultivation, and it varied with progressing of culture age.

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins or glycoproteins of non-immune origin that play an important role as recognition molecules in cell–cell or cell–matrix interactions.1 Microbial lectins include various agglutinins, adhesins, precipitins, toxins, and enzymes2 and occur widely in bacteria, protozoa, viruses, and fungi.3 Lectins have applications in blood typing and are known to exert essential functions in the immune recognition process of viral, bacteria, mycoplasmal, and parasitic infections, as well as in fertilization, cancer metastasis, and growth and differentiation several cells.4,5 After plants, mushrooms are the most widely studied group of organisms for lectins, and these lectins have gained considerable attention due to their promising biological activities.6,7 Yeast lectins are known to be involved in cell–cell interactions, pathogenesis, and cell flocculation.8 The mitogenic potential of microbial lectins has been well established as well as their ability to induce mitosis in lymphocytes/splenocytes.9

There are several reports regarding lectins from microfungi, including Rhizopus stolonifer,10Aspergillus fumigatus,11,12A. oryzae,13Penicillium marneffei,14P. thomii and P. griseofulvum,15Sclerotium rolfsii16 and Fusarium solani.17 Additionally, microfungi exhibiting lectin activity and their possible functions have been reviewed exhaustively by our group.18 Singh et al.19–21 screened 40 species of Aspergillus for the presence of lectin activity and discovered wide occurrence of lectins in this genera. Few of them have also been evidenced to possess mitogenic22–24 and immunomodulatory properties.25

Recently, Singh and Thakur26 reported lectin activity in mycelial extracts of eight Fusarium species, namely F. acuminatum, F. chlamydosporium, F. compactum, F. crookwellense, F. culmorum, F. dimerum, F. decemcellulare, and F. coeruleum. The present study attempted to explore lectin activity in ten species of Fusarium, which have been not investigated earlier. The lectins were characterized with respect to their biological spectrum and carbohydrate inhibition profile. The expression of lectin activity with respect to culture age was also investigated. The present examination could provide useful information for cataloging lectins and prompt further research on the possible roles and applications of the lectins isolated from Fusarium sp.

Materials and methodsMaintenance, growth and harvesting of microbial culturesTen Fusarium species, namely F. fujikuroi (MTCC 9930), F. beomiformii (MTCC 9946), F. diaminii (MTCC 9937), F. annulatum (MTCC 9951), F. begoniae (MTCC 9929), F. nisikadoi (MTCC 9948), F. staphyleae (MTCC 9911), F. anthophilum (MTCC 10129), F. incarnatum (MTCC 10292), and F. tabacinum (MTCC 10131) were procured from Microbial Type Culture Collection (MTCC), Institute of Microbial Technology, Chandigarh, India. All strains were maintained on potato dextrose agar slants containing potato 20.0%, dextrose 2.0%, and agar 2.0%; pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.6. Agar slants were stored at 4±1°C, until further use and were subcultured regularly at an interval of two weeks. The cultures were grown in Erlenmeyer's flasks (250mL) containing 100mL of maintenance medium without agar and were incubated at 25°C under stationary conditions for 7 and 10 days, respectively. Mycelium was harvested by filtration, washed thoroughly with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.1M, pH 7.2), and briefly pressed between the folds of filter paper. The culture supernatant was separately collected and assayed for lectin activity.

Lectin extractionThe mycelium was homogenized in PBS (1:1.5, w/v) using an ultra-high speed homogenizer (Ultra-Turrax® T25 basic, IKA-Werke, Staufen, Germany) and then ground in mortar and pestle with acidified river sand for 30min.19 The extract was centrifuged (3000×g, 20min, 4°C), and the supernatant was assayed for lectin activity.

Hemagglutination assayBlood samples drawn in Alsever's solution were stored at 4°C until further use. Erythrocyte suspension (2%, v/v) was prepared in PBS, and two-fold serially diluted mycelial extract was tested for agglutination of human, goat, pig, sheep, and rabbit erythrocytes.19 The surfaces of human and rabbit erythrocytes were modified with the enzymes, neuraminidase and protease, as described by Meng et al.27 and used in the agglutination assay. Hemagglutination was determined visually by an appearance of mat formation as an indicative of lectin activity, whereas button formation was taken as an absence of lectin activity. Lectin titer was defined as inverse of the highest dilution capable of producing visible agglutination of erythrocytes.

Hapten inhibition assayHapten inhibition assay was carried out against a panel of carbohydrates according to a method described by Singh et al.19 Lectin was incubated for 1h with an equal volume of the test solution in the wells of U-bottom microtiter plates. Erythrocyte suspension was added and hemagglutination was established visually following 30min of incubation. Button formation in the presence of carbohydrates indicated specific interaction, while mat formation was taken an absence of interaction between the lectin and the carbohydrate. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each of the specific carbohydrates was determined by serial double dilution of the test solution. MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the carbohydrate capable of inducing complete inhibition of lectin-mediated hemagglutination.

The carbohydrates tested as inhibitors were: d-ribose, l-rhamnose, xylose, l-fucose, d-glucose, d-mannose, d-arabinose, l-arabinose, d-galactose, d-fructose, d-mannitol, d-sucrose, d-maltose, d-lactose, melibiose, d-trehalose dihydrate, d-raffinose, maltotriose, inositol, meso-inositol, d-glucosamine hydrochloride, d-galactosamine hydrochloride, d-glucuronic acid, d-galacturonic acid, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, N-acetyl-d-galactosamine, 2-deoxy-d-glucose, 2-deoxy-d-ribose, porcine stomach mucin, bovine submaxillary mucin, fetuin, asialofetuin, inulin, pullulan, starch, chondroitin-6-sulphate, N-acetyl neuraminic acid, and N-glycolyl neuraminic acid. Simple sugars were tested at a final concentration of 100mM, whereas glycoproteins and polysaccharides were analyzed at a final concentration of 1mg/mL.

Lectin activity as a function of culture ageThe activity of lectin-positive cultures was determined as a function of the mycelial growth, as described by Singh et al.28 Erlenmeyer flasks (250mL) containing 50mL medium were inoculated with culture discs of 5mm diameter (containing mycelium and agar) and incubated over a period of 5–12 days at 30°C, under stationary condition. Mycelium was recovered at 24h intervals, homogenized in PBS (1:1.5, w/v), and then ground in mortar and pestle with acidified river sand for 30min. Lectin titer in the extracts was determined. For each fungal culture, an identical amount of biomass was invariably taken in same quantity of PBS over the days to determine the comparative hemagglutination as a function of culture age.

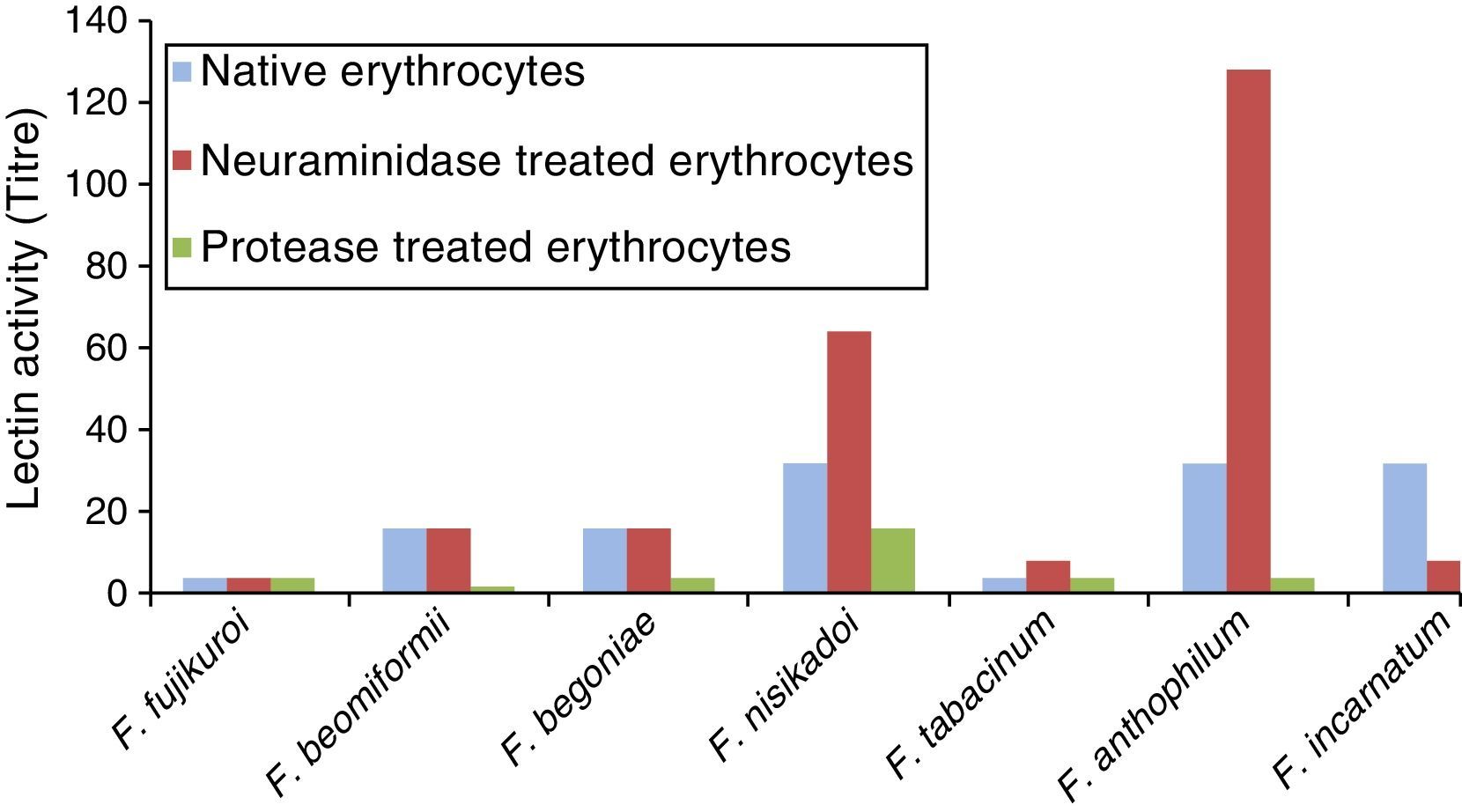

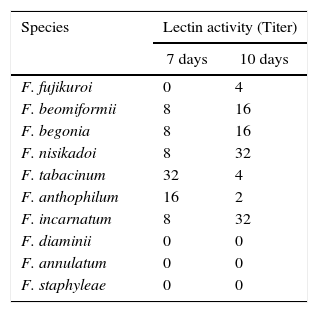

ResultsScreening of fungal cultures for the presence of lectin activityTen species of Fusarium were screened for their ability to agglutinate rabbit, goat, sheep, pig, and human (A, B, AB, and O) erythrocytes. No lectin activity in the culture supernatant was displayed by these Fusarium species, whereas mycelial extracts of seven species, namely F. fujikuroi, F. beomiformii, F. begoniae, F. nisikadoi, F. anthophilum, F. incarnatum, and F. tabacinum were found to agglutinate only rabbit erythrocytes (Table 1); and no agglutination was observed with other erythrocytes. Hemagglutination assay was also performed using neuraminidase and protease-treated rabbit and human erythrocytes. None of the extracts agglutinated even the enzyme-treated human erythrocytes. Agglutination of enzyme-treated rabbit erythrocytes with Fusarium lectins showed a variable response. Lectin extracts of F. anthophilum exhibited a 4-fold increase in the titer with neuraminidase-treated erythrocytes, whereas that of F. nisikadoi and F. tabacinum showed only a 2-fold increase (Fig. 1). However, the titer of F. incarnatum mycelial extracts was substantially reduced by neuraminidase-modified erythrocytes. Lectin titers of F. fujikuroi, F. beomiformii, and F. begoniae extracts manifested no effect of the treatment with neuraminidase on erythrocytes. F. fujikuroi and F. tabacinum extracts displayed titers similar to those of native and protease-treated erythrocytes. The activity of lectins from other Fusarium spp. was reduced after protease treatment.

Lectin activity of Fusarium spp. with rabbit erythrocytes.

| Species | Lectin activity (Titer) | |

|---|---|---|

| 7 days | 10 days | |

| F. fujikuroi | 0 | 4 |

| F. beomiformii | 8 | 16 |

| F. begonia | 8 | 16 |

| F. nisikadoi | 8 | 32 |

| F. tabacinum | 32 | 4 |

| F. anthophilum | 16 | 2 |

| F. incarnatum | 8 | 32 |

| F. diaminii | 0 | 0 |

| F. annulatum | 0 | 0 |

| F. staphyleae | 0 | 0 |

Lectin activity was determined by hemagglutination assay. The mycelial extracts were prepared from 7 day and 10 day-old cultures.

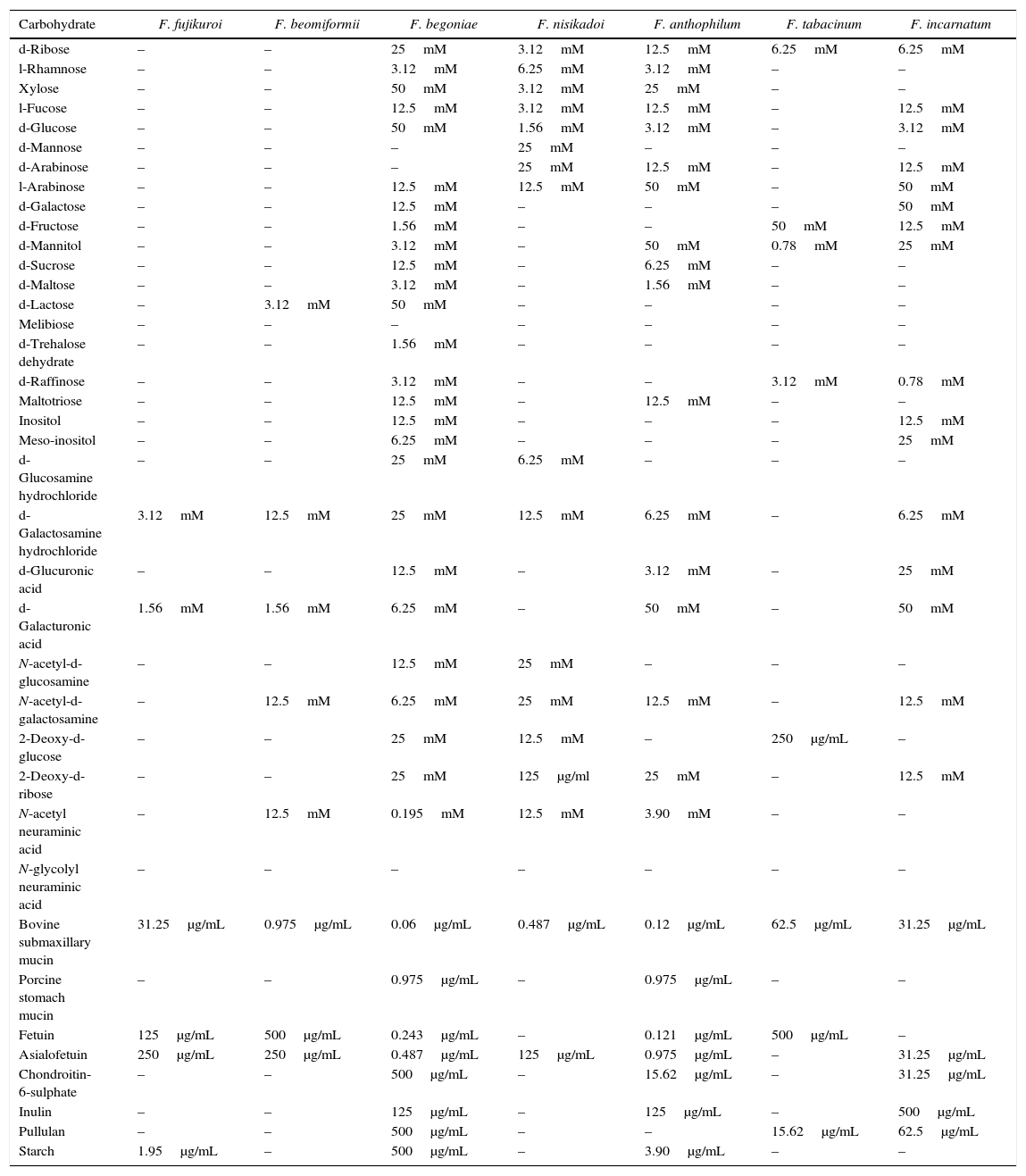

Carbohydrate specificity profile of Fusarium lectins is presented in Table 2. Few Fusarium lectins displayed exceedingly rare carbohydrate specificities. Lectin activity of the majority of Fusarium species was inhibited by d-ribose, l-fucose, d-glucose, l-arabinose, d-mannitol, d-galactosamine hydrochloride, d-galacturonic acid, N-acetyl-d-galactosamine, N-acetyl neuraminic acid, 2-deoxy-d-ribose, fetuin, and asialofetuin. F. begoniae, F. anthophilum, and F. incarnatum extracts interacted with most of the sugars tested. d-Mannose could slightly inhibit the activity of F. nisikadoi lectins. d-Galactose and d-trehalose dihydrate suppressed the activity of F. begoniae lectin. Porcine stomach mucin was inhibitory to F. anthophilum and F. begoniae lectins. However, activity of all of the Fusarium lectins was inhibited by bovine submaxillary mucin. Melibiose and N-glycolyl neuraminic acid did not suppress the action of any of the lectins. F. fujikuroi, F. beomiformii, and F. tabacinum lectins interacted with only few of the carbohydrates examined. The activity of F. fujikuroi lectin was inhibited by d-galacturonic acid, d-galactosamine hydrochloride, fetuin, and asialofetuin with respective MICs of 3.12mM, 1.56mM, 31.25μg/mL, and 250μg/mL. The lectins of F. fujikuroi and F. anthophilum strongly interacted with starch, and MICs of 1.95μg/mL and 3.90μg/mL, respectively, were observed.

Carbohydrate specificity of Fusarium spp. lectins.

| Carbohydrate | F. fujikuroi | F. beomiformii | F. begoniae | F. nisikadoi | F. anthophilum | F. tabacinum | F. incarnatum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-Ribose | – | – | 25mM | 3.12mM | 12.5mM | 6.25mM | 6.25mM |

| l-Rhamnose | – | – | 3.12mM | 6.25mM | 3.12mM | – | – |

| Xylose | – | – | 50mM | 3.12mM | 25mM | – | – |

| l-Fucose | – | – | 12.5mM | 3.12mM | 12.5mM | – | 12.5mM |

| d-Glucose | – | – | 50mM | 1.56mM | 3.12mM | – | 3.12mM |

| d-Mannose | – | – | – | 25mM | – | – | – |

| d-Arabinose | – | – | – | 25mM | 12.5mM | – | 12.5mM |

| l-Arabinose | – | – | 12.5mM | 12.5mM | 50mM | – | 50mM |

| d-Galactose | – | – | 12.5mM | – | – | – | 50mM |

| d-Fructose | – | – | 1.56mM | – | – | 50mM | 12.5mM |

| d-Mannitol | – | – | 3.12mM | – | 50mM | 0.78mM | 25mM |

| d-Sucrose | – | – | 12.5mM | – | 6.25mM | – | – |

| d-Maltose | – | – | 3.12mM | – | 1.56mM | – | – |

| d-Lactose | – | 3.12mM | 50mM | – | – | – | – |

| Melibiose | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| d-Trehalose dehydrate | – | – | 1.56mM | – | – | – | – |

| d-Raffinose | – | – | 3.12mM | – | – | 3.12mM | 0.78mM |

| Maltotriose | – | – | 12.5mM | – | 12.5mM | – | – |

| Inositol | – | – | 12.5mM | – | – | – | 12.5mM |

| Meso-inositol | – | – | 6.25mM | – | – | – | 25mM |

| d-Glucosamine hydrochloride | – | – | 25mM | 6.25mM | – | – | – |

| d-Galactosamine hydrochloride | 3.12mM | 12.5mM | 25mM | 12.5mM | 6.25mM | – | 6.25mM |

| d-Glucuronic acid | – | – | 12.5mM | – | 3.12mM | – | 25mM |

| d-Galacturonic acid | 1.56mM | 1.56mM | 6.25mM | – | 50mM | – | 50mM |

| N-acetyl-d-glucosamine | – | – | 12.5mM | 25mM | – | – | – |

| N-acetyl-d-galactosamine | – | 12.5mM | 6.25mM | 25mM | 12.5mM | – | 12.5mM |

| 2-Deoxy-d-glucose | – | – | 25mM | 12.5mM | – | 250μg/mL | – |

| 2-Deoxy-d-ribose | – | – | 25mM | 125μg/ml | 25mM | – | 12.5mM |

| N-acetyl neuraminic acid | – | 12.5mM | 0.195mM | 12.5mM | 3.90mM | – | – |

| N-glycolyl neuraminic acid | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bovine submaxillary mucin | 31.25μg/mL | 0.975μg/mL | 0.06μg/mL | 0.487μg/mL | 0.12μg/mL | 62.5μg/mL | 31.25μg/mL |

| Porcine stomach mucin | – | – | 0.975μg/mL | – | 0.975μg/mL | – | – |

| Fetuin | 125μg/mL | 500μg/mL | 0.243μg/mL | – | 0.121μg/mL | 500μg/mL | – |

| Asialofetuin | 250μg/mL | 250μg/mL | 0.487μg/mL | 125μg/mL | 0.975μg/mL | – | 31.25μg/mL |

| Chondroitin-6-sulphate | – | – | 500μg/mL | – | 15.62μg/mL | – | 31.25μg/mL |

| Inulin | – | – | 125μg/mL | – | 125μg/mL | – | 500μg/mL |

| Pullulan | – | – | 500μg/mL | – | – | 15.62μg/mL | 62.5μg/mL |

| Starch | 1.95μg/mL | – | 500μg/mL | – | 3.90μg/mL | – | – |

Note: –, non-inhibitory carbohydrates.

Simple sugars were tested at a final concentration of 100mM, while glycoproteins and polysaccharides were tested at a concentration of 1mg/mL. The test solutions were as two-fold serially diluted across the wells of microtiter plates and incubated with appropriately diluted lectin to determine minimum inhibitory concentration of specific carbohydrate.

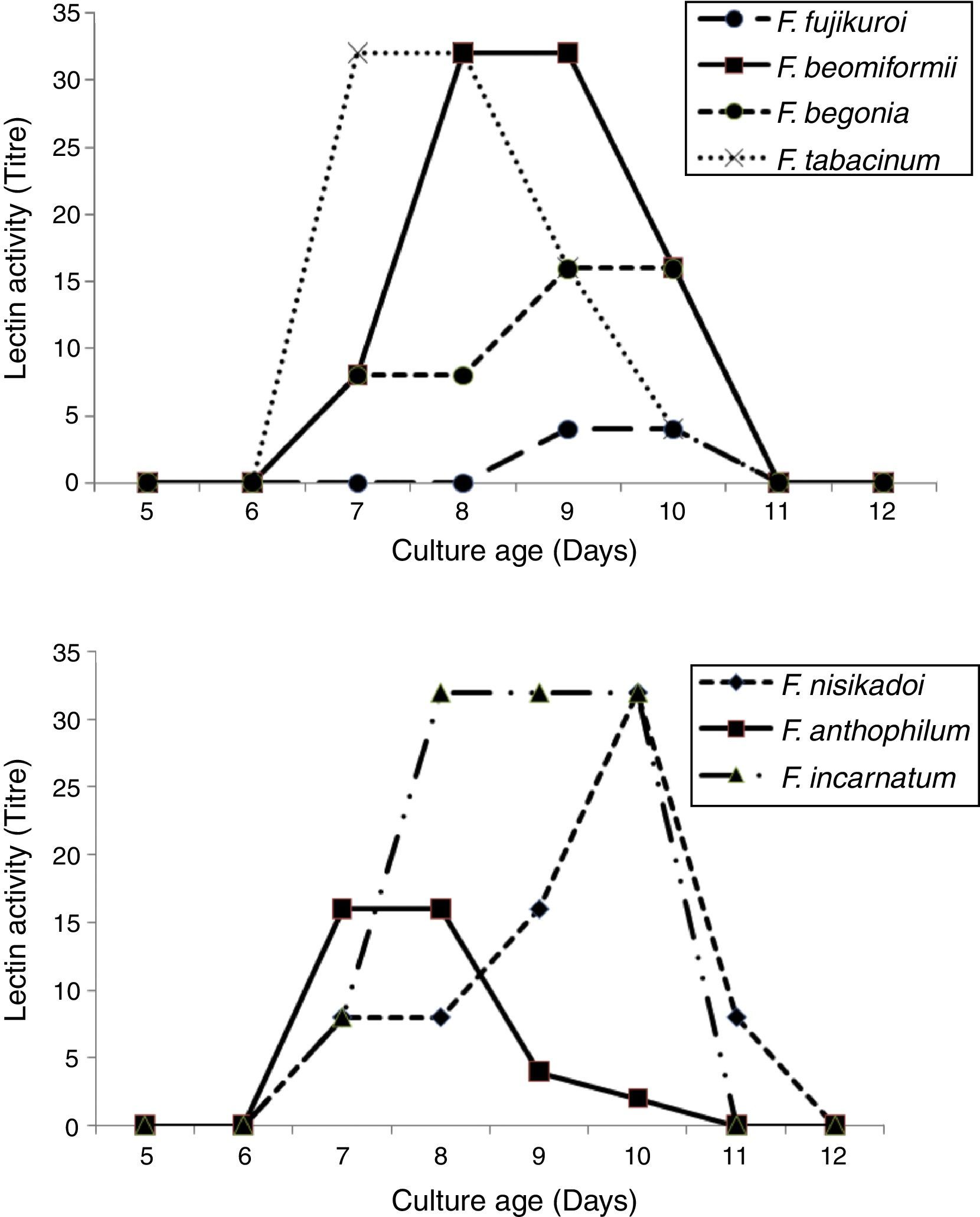

Lectin activity was determined over a period of 5–12 days to determine the influence of culture age on lectin expression. Lectin activity was expressed by 7-day old cultures of all Fusarium lectins except for F. fujikuroi, where lectin activity was expressed only by 9–10 days old cultures (Fig. 2). F. anthophilum and F. tabacinum lectins displayed maximum activity after 7–8 days of cultivation. F. incarnatum expressed a consistently high titer in 8–10 days old cultures.

DiscussionThe present study reports lectin activity from seven Fusarium species, namely, F. fujikuroi, F. beomiformii, F. begoniae, F. nisikadoi, F. anthophilum, F. incarnatum, and F. tabacinum, the presence of lectins in these species has not been explored previously. Our results and those of previous investigations conducted by Singh and Thakur26 demonstrate a wide presence of mycelial lectins in Fusarium species. In the present study, lectins from all the seven species were found to agglutinate only rabbit erythrocytes, and no agglutination with human, goat, sheep, and pig erythrocytes was observed. Ishikawa and Oishi29 reported agglutination of chick, horse and rabbit erythrocytes by culture filtrate of Fusarium sp., whereas the cell extract was capable of agglutinating human erythrocytes. Singh and Thakur26 evidenced that Fusarium lectins mostly agglutinate human and rabbit erythrocytes, and only a few of them could agglutinate sheep, goat, and porcine erythrocytes. Khan et al.17,30 found that Fusarium solani lectin agglutinated only pronase- or neuraminidase-treated human erythrocytes. Considering these findings, the hemagglutination activity of each extract was also tested against neuraminidase- or protease-treated human erythrocytes, but lectins failed to agglutinate even the enzyme-modified human erythrocytes.

Neuraminidase removes sialic acid from the surface of erythrocytes and exposes subterminal galactosyl residues, thus reducing the net negative charge on the surface of erythrocytes and increasing their agglutination ability.31 The decrease in agglutination of erythrocytes after the protease treatment indicates the removal of the preferred binding sites for Fusarium lectins. The treatment of erythrocytes with neuraminidase was also reported to increase the titers of Fusarium lectins, whereas no such effect was established after protease treatments.26

In the present study, the majority of lectins were inhibited by d-galactosamine hydrochloride, N-acetyl-d-galactosamine, asialofetuin, and fetuin. Most of the lectins manifested inhibition by free sialic acid, which was contrary to earlier findings of Singh and Thakur.26 Khan et al.30 reported specificity of Fusarium solani lectin to N-linked glycans. The lectins in this study did not interact with N-glycolyl neuraminic acid, which explains the failure of lectins to agglutinate porcine erythrocytes. Bovine submaxillary mucin is a potent inhibitor of Fusarium lectins, whereas porcine stomach mucin is a weak inhibitor. The former contains N-acetyl neuraminic acid, N-glycolyl neuraminic acid, N-acetyl 9-O-acetyl neuraminic acid, and 8,9-di-O-acetyl neuraminic acid. On the other hand, mucin from porcine stomach contains 90% N-glycolyl neuraminic acid, 10% N-acetyl neuraminic acid, and traces of N-acetyl 9-O-acetyl neuraminic acid.32 Free N-acetyl neuraminic acid could inhibit the activity of few Fusarium lectins, but N-glycolyl neuraminic acid had no inhibitory effect, which justifies the strong inhibitory potential of N-acetyl neuraminic acid containing glycoprotein bovine submaxillary mucin and weak binding with porcine stomach mucin. Fetuin mainly contains N-glycolyl neuraminic acid,33 and most of the lectins discovered in representative Fusarium species showed only weak interaction with fetuin. The results depict the inhibition of lectin activity of Fusarium extracts by sialoglycoconjugates. However, inhibition by asialofetuin corroborates the earlier findings, where lectins specific for sialic acid also manifested inhibition by the asialo form glycoproteins.34,35

The results of the present investigation suggest an affinity of Fusarium lectins to O-acetyl neuraminic acid, which is also reflected in the erythrocyte specificity. The lectins bound to rabbit erythrocytes, which contain N-O-acetyl neuraminic acid. Human A, O, sheep, and goat erythrocytes have surface glycoconjugates rich in N-acetyl neuraminic acid,32 which might have been responsible for the failure of lectins to agglutinate these erythrocytes. However, the augmentation of lectin titer after the neuraminidase treatment and the fine specificity of Fusarium lectins cannot be completely explained at this point. These might be due to the presence of more than one lectin in the extracts tested.

Fusarium lectins were found to be developmentally regulated. There was no increase in lectin activity with the progressing culture age and a corresponding rise in the protein content of mycelia, indicating that the lectin activity was not a function of growth rate alone. The developmental regulation of Fusarium lectins corroborates to earlier reports on Fusarium sp.26 and other microfungi.15,21,28,36,37

In the present study, the large number of lectin-positive species capable of agglutinating only rabbit erythrocytes indicates a high incidence of sialic acid-specific lectins amongst the members of this genus. Although hemagglutinating activity is not a powerful tool to define minor differences in affinity between different molecules, recognition of different glycan structures suggests the widespread occurrence of receptors for Fusarium lectins. Normal tissues have N-acetyl neuraminic acid, whereas malignant cells contain O-acetyl sialic acid.32 These lectins can be a valuable tool for localization and assessment of glycoconjugates containing O-acetyl sialic acid. The unique carbohydrate specificity of Fusarium lectins invites further research on this genus. The carbohydrate specificities and hemagglutination profiles indicate that more than one lectin may be present in the extracts. However, further investigations are required to establish the subtle saccharide specificity of Fusarium lectins reported herein.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors are thankful to Head, Department of Biotechnology, Punjabi University, Patiala for providing the necessary laboratory facilities during the whole course of the study.