Atrial dissection is an uncommon entity after cardiac surgery. There is not an extensive knowledge about pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management.

We report the case of a 65 year-old male with angina pectoris and diagnosed of three vessels stenosis in angiography. Three coronary artery bypass grafts were performed with on-pump technique. After the operation, the echocardiography showed heterogeneous material in left atrium occupying most of the left atrium. Left atrial wall dissection was diagnosed. Due to hemodynamic stability, we decided a conservative management and a close follow up with images test (echocardiography and computed tomography). Six months after the operation, the patient remains asymptomatic.

High values in the pressure line of retrograde cardioplegia could lead to left atrial dissection. Conservative approach may be an option in stability situation, requiring a close follow up.

La disección de aurícula izquierda es una entidad infrecuente tras una cirugía cardíaca. No existe un gran conocimiento sobre esta entidad, su presentación clínica y manejo.

Presentamos un caso de un varón de 65 años con angina pectoris y diagnóstico de estenosis de 3 vasos en la angiografía. Se realizó un triple bypass coronario con circulación extracorpórea. Tras la cirugía, el ecocardiograma mostarba un material heterogéneo que ocupaba la mayor parte de la aurícula izquierda. El paciente fue diagnosticado de disección de la pared auricular izquierda. Debido a la estabilidad hemodinámica, se optó por el manejo conservador y seguimiento estrecho con pruebas de imagen (ecocardiografía y tomografía computarizada). Seis meses después de la operación, el paciente no refiere ningún síntoma cardiovascular.

Valores elevados en la línea de presión de la cardioplejía retrógrada pueden ocasionar una disección de la pared de la aurícula izquierda.

El manejo conservador puede ser una opción en situación de estabilidad, con un seguimiento estrecho.

Atrial dissection is an uncommon entity, defined as a forced separation of layers of the left atrial creating a gap from the mitral or tricuspid annular area to the interatrial septum or left atrial wall.1 As a rare and severe complication after cardiac surgery, there is a limited knowledge about pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management. A spontaneous etiology has been described, although most cases appears iatrogenically due to cardiac surgery.2

Left atrial dissection (LAD) is more frequently associated with mitral valve surgery and it is extremely uncommon in isolated bypass grafting. We present a left atrium dissection developed in a 65-year-old male underwent triple coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) on-pump and it was successfully managed conservatively.

Case reportA 65-year-old male with medical history of diabetes mellitus noninsulin dependent and arterial hypertension was urgently admitted with suspected unstable angina (Canadian Cardiovascular Society III). Coronary angiography showed severe lesions in anterior descending artery, circumflex and right coronary artery. With these findings, it was decided to perform triple CABG.

Preoperative transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) relevant findings presented moderate left ventricular hypertrophy with preserved left ventricular function. Aortic valve had a mild regurgitation. The left atrium was slightly dilated with a posterior–anterior diameter of 40mm with no mitral regurgitation.

Before entering the operating room, the patient had persistent symptoms of myocardial ischemia despite the optimal medical treatment. Because of refractory symptoms we started with the intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation via left femoral artery (Arrow, Maquet Medical, Germany) (IABP) prior to anesthetic induction. Anesthetic procedures were uneventful.

The surgical procedure was performed using the standard cannulation. Blood cardioplegia at a ratio of 4:1 was delivered anterogradely and retrogradely. The retrograde cardioplegia (RCP) catheter (DLP® Silicone Coronary Sinus Perfusion Cannula with Manual-Inflate Cuff, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN) equipped with pressure monitor line was placed in the coronary sinus and it was verified intraoperatively by transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) visualization in four chambers view, 0°. After first session of anterograde cardioplegia, 50cc of retrograde cardioplegia were infused. The monitorization revealed a large RCP pressure increase above 120mmHg and perfusionist immediately stopped the infusion and RCP was removed. A second dose of anterograde cardioplegia was infused after 20min of isquemia time. Triple coronary bypass was performed using bilateral mammary arteries as a Y graft and one saphenous vein. During hemostatic time there was no evidence of bleeding and patient was admitted in Critical Care Unit.

Initially upon entering the unit, noradrenaline was initiated at low dose due to hypotension caused by vasoplegia. The patient was extubated 4h later without incidents. Transthoracic echocardiography was performed in spontaneous ventilation to reevaluate biventricular contractility. Surprisingly, it showed a new large heterogeneous image in the left atrium that occupied a wide part of it without Doppler flow inside.

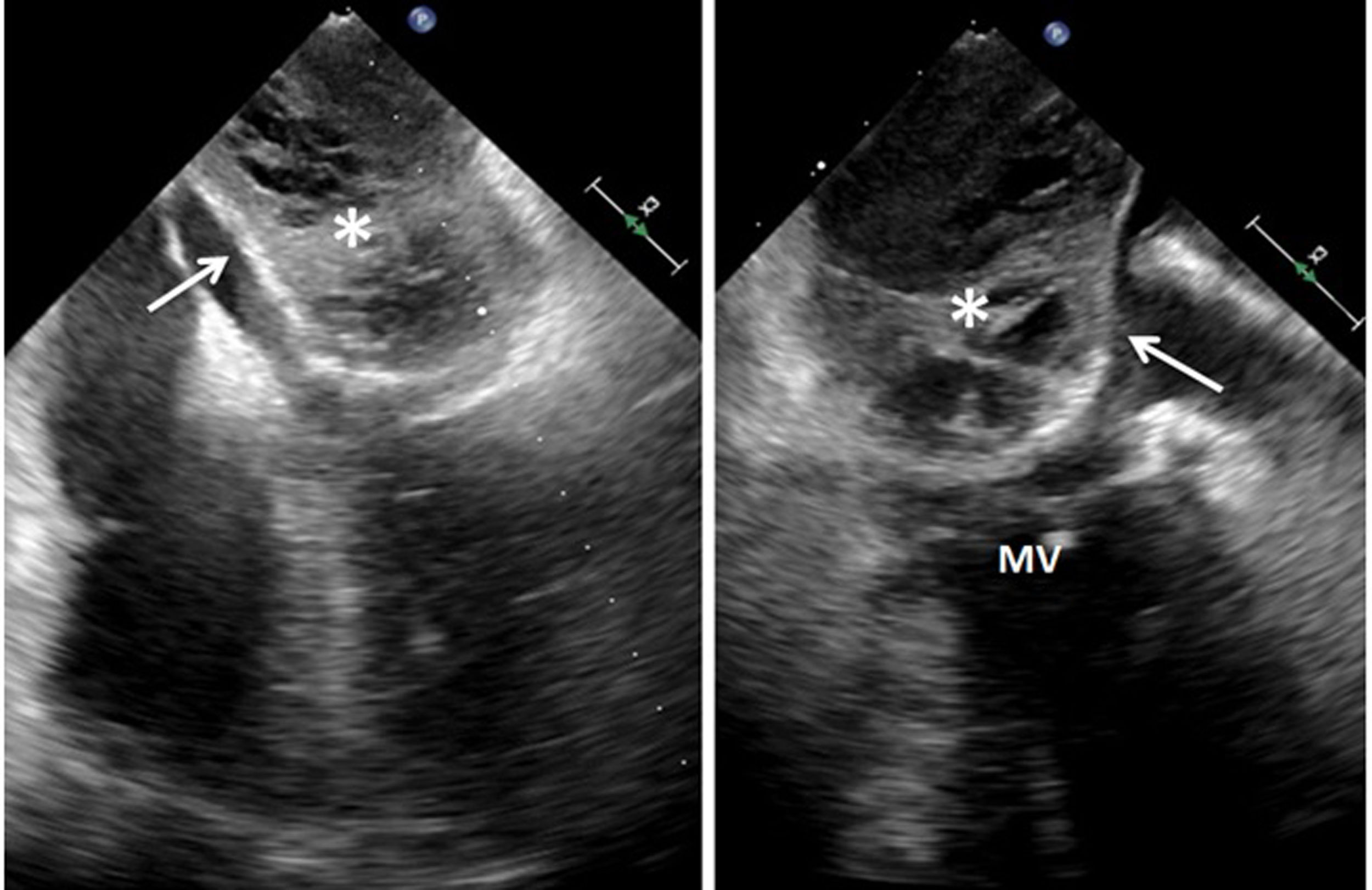

Urgent TEE showed a large mass (51mm×52mm) occupying almost the entire left atrium, with heterogeneous echodensity and ecolucent images without Doppler flow or SonoVue® (sulphur hexafluoride microbubbles) echocontrast filling (Fig. 1). That image was suggestive of atrial wall dissection with probable entry at the level of the coronary sinus due to its location. Objectivation of cul-de-sac in its ends supported our hypothesis. In this case, although the dissected lumen was large and right ventricle was borderline, it did not develop any blood flow obstruction and no mitral valve changes with no mitral regurgitation. The clinical evolution was satisfactory, withdrawing IABP and pharmacological support during the first 36h of the postoperative course. Right heart catheterization was no performed.

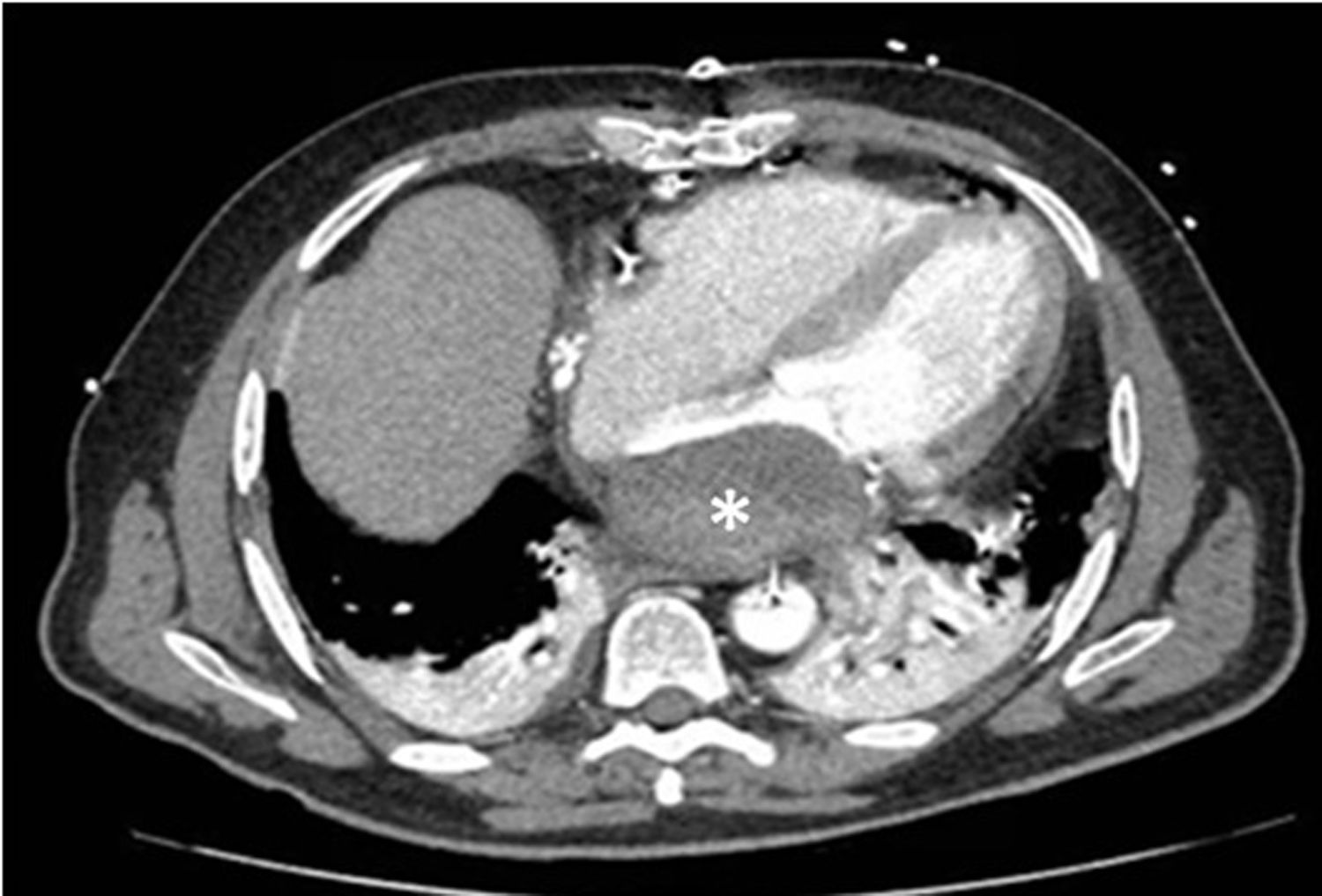

Therefore, we managed LAD conservatively with close observation. Patient received antiplatelet treatment and no-anticoagulation due to his high risk of let wall rupture and his sinus rhythm. During the in-hospital stay, a tomography cardiac scan was requested showing findings compatible with the presence of LAD (Fig. 2).

After 6 days, the patient was discharged with subsequent follow-up by Cardiology Department.

DiscussionThe appearance of LAD in perioperative period of CABG is extremely rare. In our case, clinical and echocardiographic dissociation is especially remarkable. Managing LAD in the immediate postoperative period is not trivial as a result of its possible clinical impact. Surgical intervention was thoroughly discussed interdisciplinary but considering the patient's hemodynamic stability the risk-benefit analysis favored a conservative management.

LAD is truly unusual even more after CABG surgery as inform some reviews. Some reviews of published cases set up mitral valve surgery as the most frequent etiology recently. Fukuhara analyzed his results from 1991 to 2012, showing a prevalence of 0.02% after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and 0.16% of mitral valve patients.3 Martinez-Sellés et al. submitted in their work a prevalence of 0.84% in the postoperative follow-up of mitral valve patients.4 Analyzing etiologies trend over time there is a light increase in percutaneous procedures related to the development of these new techniques.5,6 Moreover, It has been related with a cardiac tumor appearance. Physiopathology would be related with the presence of a pressurized inflow into the entry of the dissection which can be originate from the left ventricle, left ventricular outflow tract and retrograde cardioplegia infusion. Last one would probably have been the origin of our case.

Use of retrograde cardioplegia is a widely established technique. Retrograde myocardial cardioplegia has many advantages such as uniform distribution of cardioplegia despite proximal coronary vessel occlusion or critical stenosis, it colds down and protect right ventricle and helps to avoid the risk of distal embolization.7 There are many reports of coronary sinus injury or rupture due to an RCP cannula, but few reports of LAD.8,9 Risk of these problems may be further reduced. Manual palpation, damp pressure trackings and TEE appearances are helpful in diagnosing this problem. The perfusionist should check infusion pressures and the coronary sinus (CS) waveform during RCP delivery. Changes in the waveform may indicate cannula malposition, loss of balloon seal, or, more rarely, CS rupture; such changes should prompt immediate cessation of RCP delivery.

The dissection triggers a large cavity between the endocardium and epicardium of the left atrium. LAD could result in hemodynamic compromise due to occlusion of the left atrial cavity, pulmonary veins or mitral inflow obstruction emerging hemodynamic instability, low cardiac output and pulmonary edema. In our patient clinical onset was different. He had hemodynamic improvement that allowed the withdrawal of mechanical and pharmacological supports in the first 36h of the postoperative course. Because of his clinical stability and his satisfactory evolution, surgical treatment was ruled out.

LAD Surgical treatment is the most frequently used option. There are different surgical approaches including entry closure10 and internal drainage connecting false lumen with the right atrium.11 Despite the absence of clinical guidelines for the management of this pathology, there are some aspects that should lead us to perform an active attitude such as instability hemodynamic due to flow obstruction or acute rupture provocating cardiac tamponade.

ConclusionsLAD after coronary artery bypass grafting is an extremely rare entity. Perioperative echocardiography is an essential examination for patients undergoing cardiac surgery. A conservative approach with a close follow up in asymptomatic patient could be an appropriate strategy.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained by the patient to publish the results in the article.

Conflict of interestNone.