Coronary artery fistula (CAF) are a major coronary anomaly which involve one or more coronary arteries abnormally communicating with one of the cardiac chamber or the great vessels adjacent to the heart. The incidence of CAF is 0.05–0.9% in general population and the majority are congenital. Acquired CAF are less common and may occur after cardiac surgery or catheterism, chest trauma or disease related. We present a case of a 6-month-old male infant who underwent intracardiac repair for Tetralogy of Fallot. During the immediate postsurgical period, a CAF from the left coronary artery to the right ventricle (RV) was detected. Spontaneous closure occurred one month after the initial diagnosis.

Las fístulas arteriales coronarias (FAC) son una malformación coronaria mayor que consiste en una o más arterias coronarias anormalmente comunicadas con una de las cámaras cardíacas o de los grandes vasos adyacentes al corazón. La incidencia de las FAC es de 0.05-0.9% en la población general, y la mayoría son congénitas. Aquellas adquiridas son menos comunes y pueden aparecer tras cirugía cardiaca o cateterismo, traumas torácicos o en algunas patologías. Presentamos el caso de un lactante de 6 meses al que se realizó cirugía de Tetralogia de Fallot mediante técnica de reparación valvular. Durante el postoperatorio inmediato se detectó una fístula coronaria desde la arteria coronaria izquierda al ventrículo derecho. Un mes después del diagnóstico tuvo lugar su cierre espontáneo.

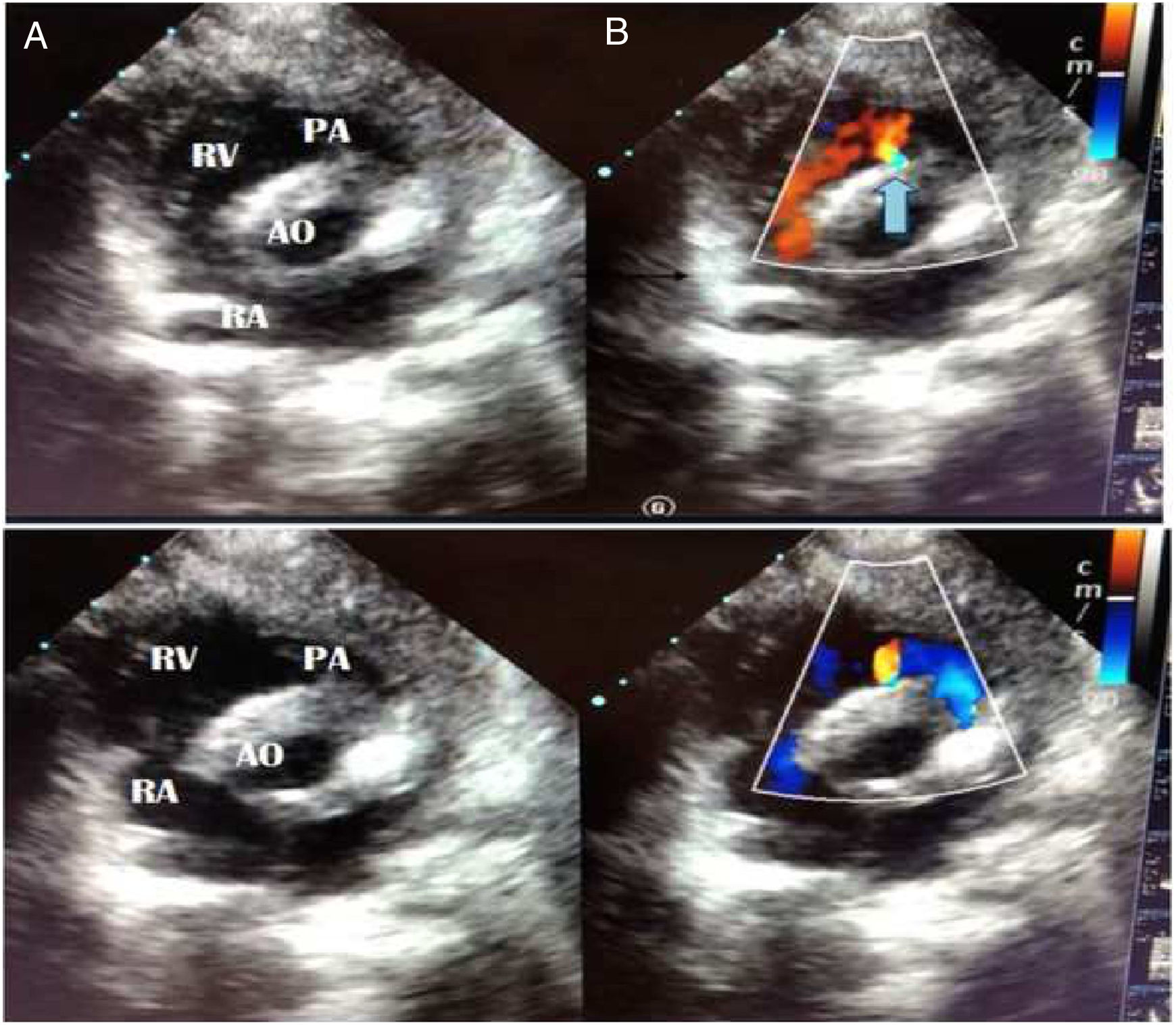

We present a case of a 6-month-old male infant who underwent intracardiac repair for Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF). He was operated by total repair approach with pulmonary valve preservation and after surgery he was shifted to Intensive Unit Care. Informed consents for surgery and publication were provided in accordance with national legislation. In an ultrasound routine check-up during the immediate postsurgical period, a constant pulsatile flow in the interventricular septum which reached the right ventricular outflow tract was detected, compatible with a coronary artery fistula (CAF) from the left coronary artery to the right ventricle (RV) (Fig. 1, Video 1.)

Short axis projection in sonography. It shows continuous flow in diastole (A) and systole (B). The blue arrow marks the fistula location. Its origins appears to be in the interventricular septum and it reaches the right ventricle infundibulum. RA, right auricle; RV, right ventricle. AO, aorta; PA, pulmonary artery.

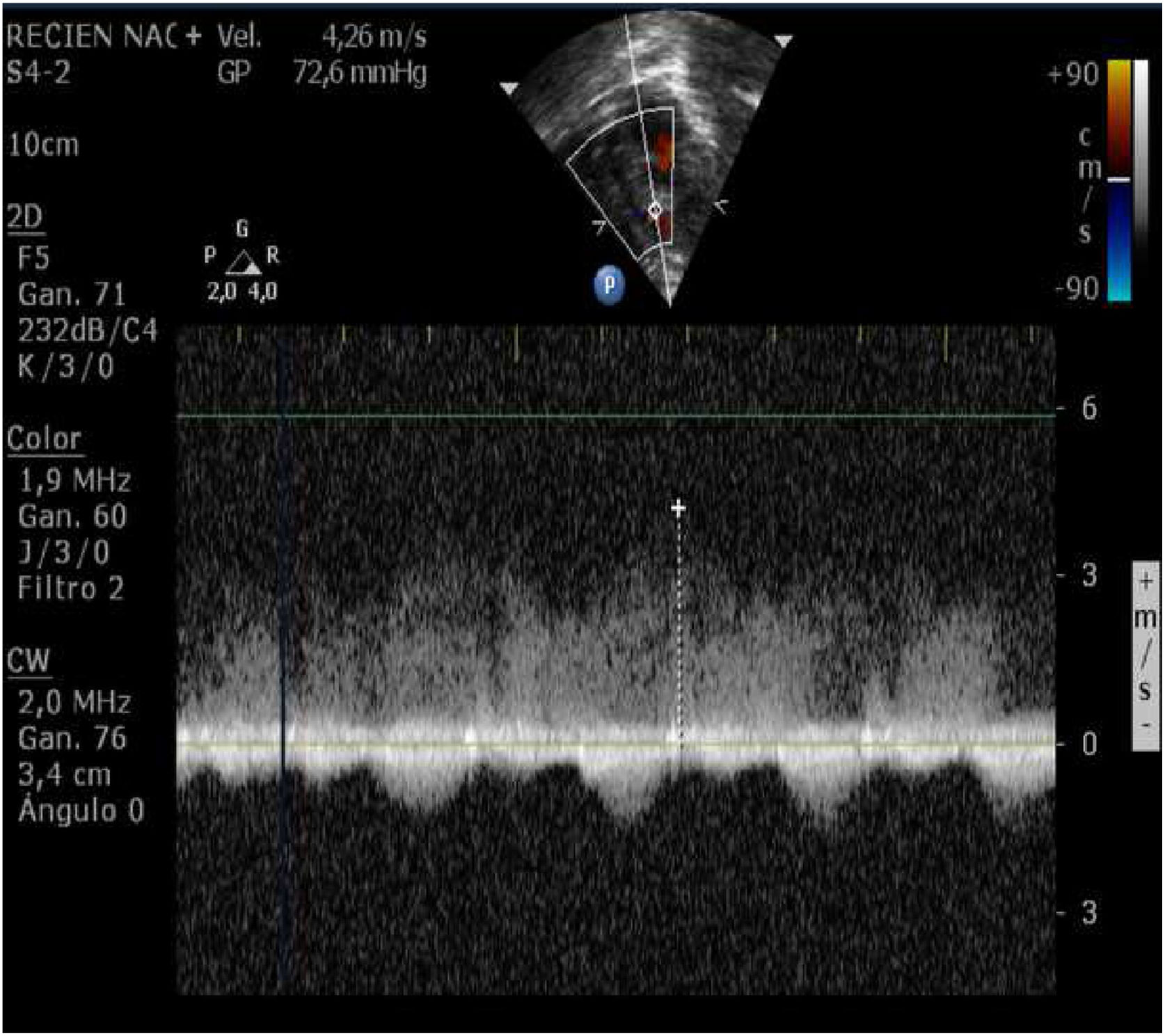

We performed an enzimatic curve, an ultrasound image and an ultrasound continuous doppler (Fig. 2) and there were not any evidence of myocardial ischemia. The patient remained asypmtomatic during the hospital stay and progressed correctly. Spontaneous closure of the CAF occurred one month after the initial diagnosis.

CAF are a major coronary anomaly which involve one or more coronary arteries abnormally communicating with one of the cardiac chamber or the great vessels adjacent to the heart.1 The incidence of CAF is 0.05–0.9% in general population and the majority are congenital.4 Acquired CAF may occur after cardiac surgery or catheterism, chest trauma or disease related (acute myocardial infarction, Kawasaki disease, etc.).1–3 Those CAF which are detected after TOF surgery are quite frequent and they usually imply the RV.2,5 Differential diagnosis of CAF includes the following: persistent ductus arteriosus, pulmonary arteriovenous fistula, ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm, aortopulmonary window, ventricular septal defect, prolapse of the right aortic cusp with a supracristal ventricular septal defect, internal mammary artery to pulmonary artery fistula, and systemic or thoracic arteriovenous fistula.6,7

Small fistula are asymptomatic, but in the large ones, symptoms may be present at an early age.1 When the symptoms are present, they may be explained as a result of the coronary steal phenomenon, which usually present as effort angina (during the exercise in adults or during feeding in infants), irritability, tachypnea, sweating, or even failure of thrive.1 There is general agreement that the symptomatic patients should be treated with either transcatheter approach or surgical ligation depending on the characteristics of the fistula.1–3 However, the management of asymptomatic pediatric CAF patients remains a controversial topic.1–3 Referring to those, a conservative follow-up with careful monitoring is suggested because of the rare CAF-related complications and, in some cases, as it is ours, they tend to present an spontaneous closure.1,3

Conflict of interestEach of the authors claims that there are no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise and confirms that there are no prior publications or submissions with any overlapping information and is not currently under consideration by any other journal.