Coronary artery fistula are unusual congenital anomalies, with low prevalence in general population. Most of them connect to right cavities, while only 1 of 5 cases end up in the pulmonary artery. Their clinical presentation is commonly asymptomatic, and is mainly found as an incidental diagnosis in coronary angiography or coronary angioTAC.

We report a young adult without comorbidities who presented with chest pain. Biomarker elevation was confirmed, and acute coronary syndrome was suspected. Coronary angiography revealed Left Anterior Descending Artery (LAD) artery atherosclerotic disease. And transthoracic echocardiogram founded a high flow coronary to pulmonary artery fistula. Therefore, patient was successfully treated trough coronary artery bypass graft and proximal–distal fistula closure. The postoperative coronary angiography displays an appropriate left mammary – left anterior descending artery bypass flow, resulting in adequate LAD competitive flow and coronary artery fistula resolution.

Coronary artery fistulas are mostly asymptomatic and rare, nonetheless when their diameter is greater than 2mm they can develop symptoms. In some cases, they can produce coronary steal and simulate an acute coronary syndrome due decreasing coronary flow, as was evidenced in the initial catheterization of the patient presented.

Las fístulas de arteria coronaria son anomalías congénitas poco comunes, con prevalencias muy bajas en la población general. En la mayoría de casos el trayecto fistuloso desemboca en cavidades derechas, mientras que aproximadamente 1 de cada 5 desembocan en la arteria pulmonar. Su presentación tiende a ser asintomática, por lo que se diagnóstica de forma incidental cuando es realizado un cateterismo cardiaco o una angiotomografía coronaria por otras causas.

Se presenta el caso de un paciente adulto joven sin comorbilidades, quien ingresa por cuadro clínico de dolor torácico. El paciente presenta biomarcadores positivos, por lo cual se sospecha cursa con un síndrome coronario agudo y es llevado a un cateterismo cardiaco identificando enfermedad arterioesclerótica en la arteria descendente anterior (ADA). Como estudio complementario se realiza un ecocardiograma transesofágico que sugiere la presencia de una fistula coronaria de alto gasto con trayecto al tronco pulmonar. Por tal motivo es llevado a cirugia, en donde se realiza un bypass desde la arteria mamaria izquierda a la ADA, aunado a un cierre proximal y distal del trayecto fistuloso. En el seguimiento, el cateterismo de control postoperatorio evidencia un bypass coronario permeable con flujo competitivo en la ADA y ausencia de la fistula coronario-pulmonar.

Las fistulas coronario-pulmonares son generalmente asintomáticas y poco frecuentes, sin embargo, al presentarse con diámetros mayores a 2 mm pueden generar síntomas. A tal punto de producir robo coronario y simular un síndrome coronario agudo por la disminución del flujo coronario, como fue evidenciado en el cateterismo inicial del paciente presentado. Revascularización miocárdica, fístula, enfermedad coronaria, síndrome coronario agudo.

Coronary artery fistulas are anatomical anomalies, in which there is an abnormal vascular connection between the coronary artery and a cardiac chamber, a great vessel, or another vascular structure.1 These fistulas are rare diseases in the general population, with a prevalence of 1–2%,2,3 corresponding to 0.27–0.4% of congenital cardiac defects.3 Their diagnosis tends to be incidental, reported in 0.05–0.25% of patients undergoing coronary arteriography and 0.88% on cardiac angiotomography for concomitant pathology.2,4

Fistulas of those affected are connected with the right cardiac chambers in 46% and with the pulmonary artery in 17% of defects.4 In 10–16% of cases fistula connections are numerous, originating from the same vessel or from different vascular structures.5 In addition, it has been described that up to 19% of those affected may present a concomitant aneurysm of the congenital coronary defect.1

We present a case of a young patient who presented with precordial pain. He underwent to coronary angiography and was diagnosed with severe coronary artery disease of the Left Anterior Descending artery, associated with an incidental finding of a coronary–pulmonary fistula with high output, managed surgically. The presentation of this case follows the SCARE guidelines recommendations.6

Case presentationA 36-year-old male patient with no relevant medical history, consulted for 12 hour of oppressive chest pain radiated to left arm. Physical examination and systemic review were unremarkable, with normal vital signs and without signs of heart failure. An electrocardiogram was performed with no abnormal findings, and cardiac biomarkers elevation was founded.

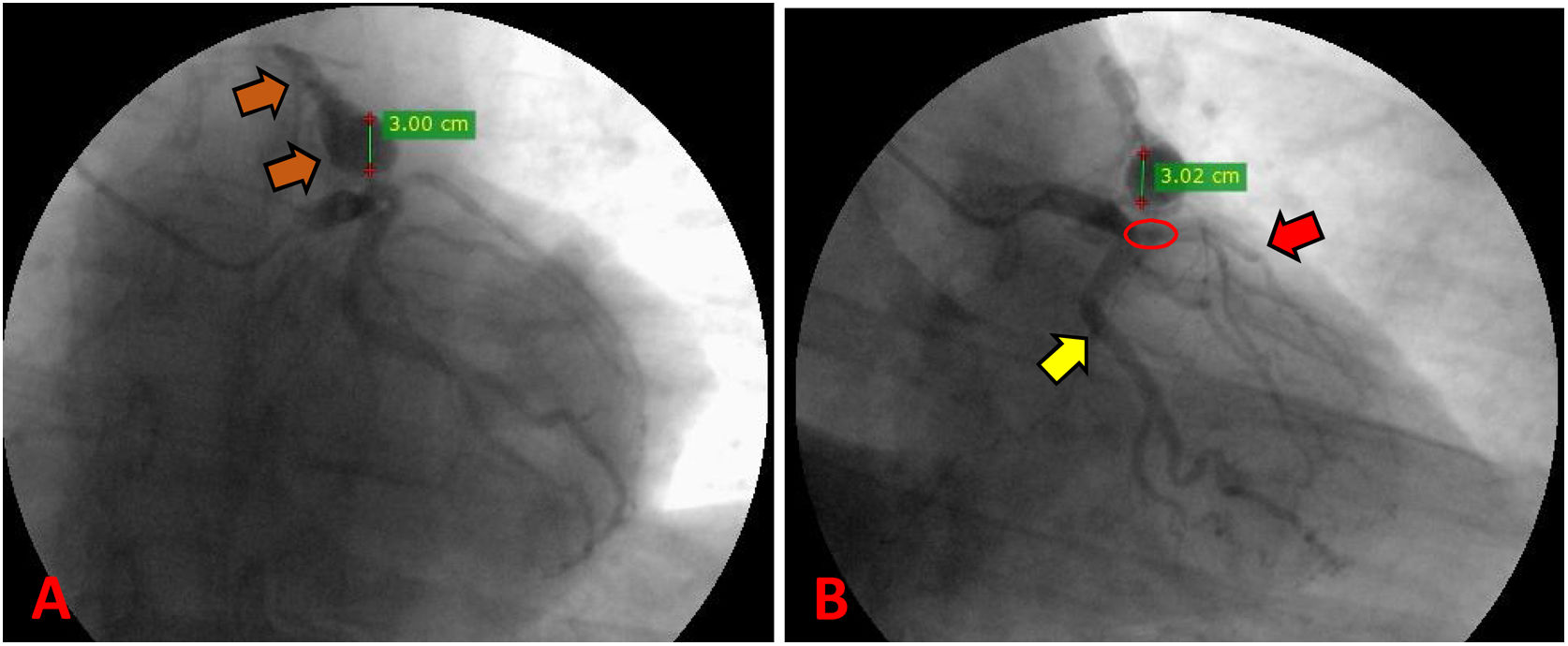

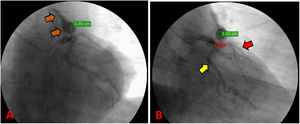

There was made a diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction without ST elevation, and the patient underwent coronary angiography. The exam reported a severe coronary artery disease with occlusion of 75% of the left anterior descending artery proximal third, and the presence of a giant aneurysm in an anomalous vascular structure originating from the same artery (Fig. 1). These findings were complemented with a transesophageal echocardiogram, which located a high output coronary fistula from the left anterior descending artery that flowed to the main pulmonary trunk, and a concomitant fusiform aneurysmal dilatation with 30mm in diameter at 13mm from the ostium.

Preoperative coronary angiography. (A) Path of the coronary pulmonary fistula from the LAD to the main pulmonary trunk (orange arrow). (B) Suspected presence of 75% severe coronary artery disease in the proximal LAD (red circle); the path of the LAD (red arrow); the path of the circumflex artery (yellow arrow).

The medical board concluded that the patient had severe coronary artery disease of the LAD and a high-flow coronary pulmonary fistula, with an aneurysmal dilation that does not compromise the left anterior descending artery. Therefore, it was decided to perform surgical management.

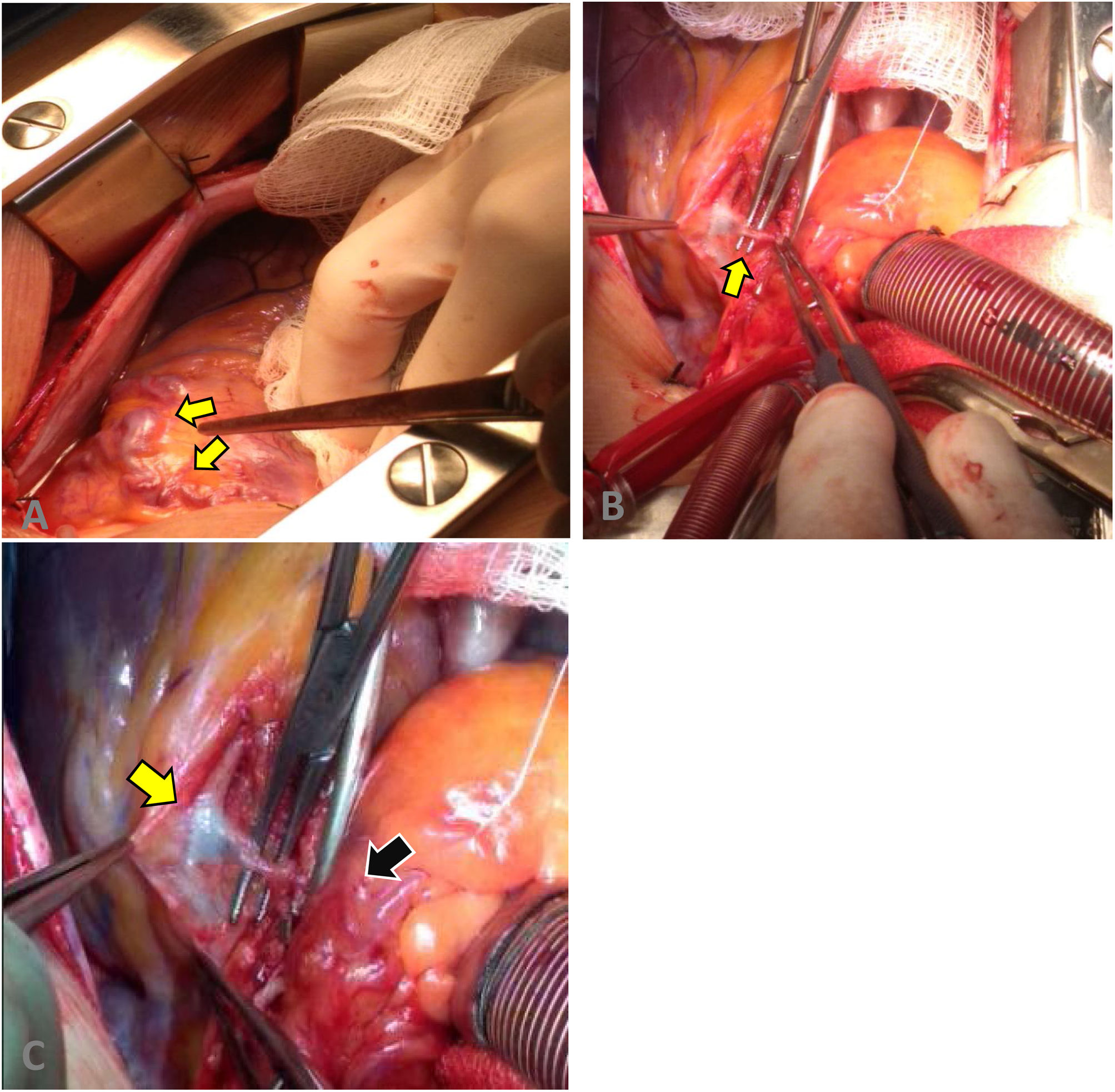

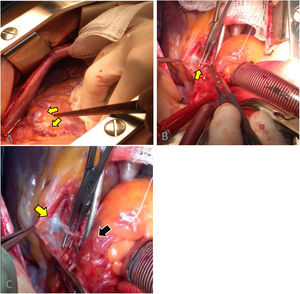

A surgical approach was performed by median sternotomy, and then led to extracorporeal circulation (ECC) with venous cannulation in the right atrium and arterial cannulation in the ascending aorta, the aorta was clamped to infuse cardioplegia until cardiac activity ceased. We proceeded to locate the coronary–pulmonary fistula, which was initially explored and finally brought to proximal and distal closure, in the left anterior descending artery and the pulmonary artery respectively, as well as the closure of its collateral branches (Fig. 2). Finally, an end-to-side anastomosis of the distal end of the IMA to the LAD was performed with 7/0 prolene.

Surgical procedure. (A) Fistula and aneurysmal dilatation in the superior and proximal portion of the left coronary artery. (B) Dissection of the coronary–pulmonary fistula. (C) Fistulous path from the proximal left anterior descending artery (yellow arrow) to the pulmonary trunk (black arrow).

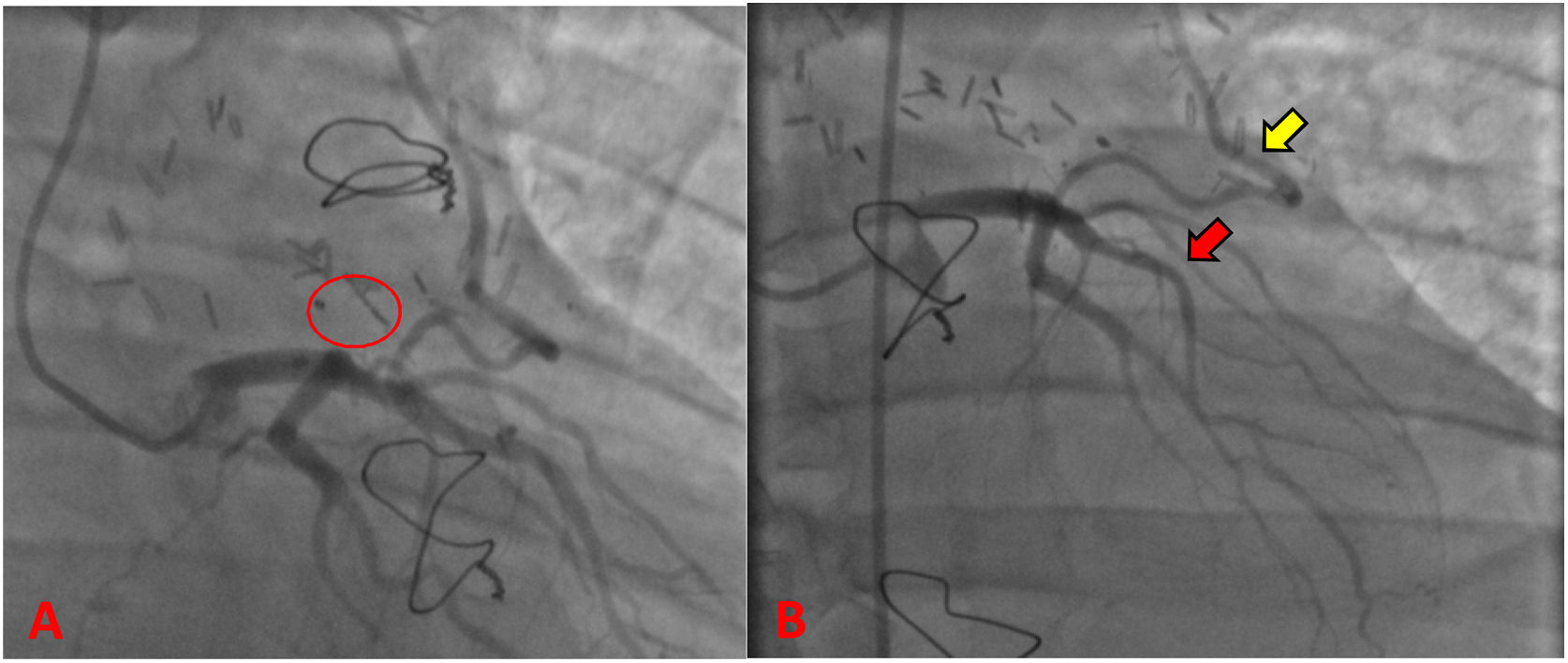

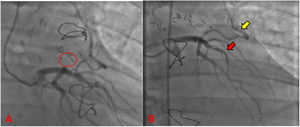

During the hospitalization, he was taken to coronary angiography for control (Fig. 3), revealing LAD without atherosclerotic disease, the IMA-LAD bypass was patent and the coronary–pulmonary fistula was resolved. The patient was discharged on the sixth postoperative day with pharmacological treatment and follow-up by cardiovascular surgery and cardiology. In the 3rd postoperative month, the patient reported he had returned to normal physical and work activities without chest pain or any other symptoms. In addition, normal results were evidenced in transthoracic echocardiogram and Holter.

DiscussionThe presence of coronary–pulmonary fistulas that do not arise from the right coronary artery and end in the ventricle or atrium of the same side is uncommon.3,4 However, we present the case of a fistulous tract originating in the LAD that ends in the main trunk of the pulmonary artery.

In most cases, fistulas are asymptomatic. However, those with a diameter greater than 2cm and with a pulmonary/systemic ratio (Qp/Qs)≥1.5 are characterized by high output and associated with ischemic symptoms appearance, which can have a chronic or acute presentation. The presence of symptoms in patients is related to coronary arrest syndrome. It is caused when blood flow is diverted by the vascular malformation by having less resistance, generating a decrease in coronary flow and areas of myocardial hypoperfusion. This syndrome clinical presentation is characterized by chest pain, which may be associated with dyspnea, diaphoresis or pain radiation. The previous symptomatology may initially lead to the suspicion of a coronary syndrome, as occurred in our patient and in multiple case reports in the literature.3,7

There may also be cases in which, due to a high-flow fistula there is a decrease or absence of coronary artery flow. These happened in the case described, where the initial catheterization indicated a decrease in LAD flow, which led to consider the diagnosis of a severe atherosclerotic coronary disease. It was in the postoperative period that it was ruled out, when the resolution of the lesion was observed after the closure of the vascular malformation. Therefore, coronary angiography full review is very important, taking into account that in some cases the absence or decrease of coronary flow may be caused by the presence of a vascular malformation.

The treatment of coronary–pulmonary fistula will depend on the size of the fistula and the associated flow. Patients with small diameter fistulas are given expectant treatment, since they are usually asymptomatic and present low flow.2,7 This is reported by Salazar and Sherif, who described expectant management for fistulas with diameters between 2 and 3mm without high flow.2,7 Fistulas with an intermediate diameter are usually smaller than 2cm. Treatment for those associated with high-flow can be deliver by non-invasive interventions with transcatheter closure. This is the case of Amicone et al. who reported a 3mm fistula with high flow, which was successfully closed by an endovascular approach.8 Finally, those patients who present high flow larger diameter fistulas would benefit more from an open surgical intervention, as is described by Dadkhah-Tirani and Favaloro, with the successful surgical management of high flow fistulas with a diameter between 10 and 15mm4,9 (Table 1). In accordance with previous literature, it was decided to perform an open surgical closure on the patient presented.

A comparison between case reports of coronary–pulmonary fistula.

| Author | Age | Sex | High-flow presence | Diameter and length | Associated symptoms | Treatment | Mortality | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figueroa R, et al. | 36 | Male | Yes | 30mm | Left chest pain radiating to the left arm | Surgical open closure | No | Postoperative angiography reports the absence of coronary artery fistula and patent LAD-AMI bypass. |

| Sherif K, et al.2 | 57 | Female | No | 2–3mm | Left chest pain radiating to the left arm | Expectant management | No | Symptoms not related to fistula, management by gastroenterology is decided. |

| Amicone S, et al.8 | 58 | Female | Yes | 3mm and 5cm | Progressive dyspnea | Endovascular closure | No | One-month follow-up reports absence of symptoms and improvement of dyspnea. |

| Favaloro R, et al.9 | 48 | Female | Yes | 10–15mm | Angina and exertional dyspnea | Surgical open closure | No | In the 3rd month, CT and coronary angiography showed fistula resolution |

| Dadkhah-tirani H, et al.4 | 69 | Female | Yes | No data | Retrosternal pain and diaphoresis associated with exertion | Surgical open closure | No | In the 4th month, nuclear scintigraphy revealed normal myocardial perfusion and no residual fistula. |

| Salazar J, et al.7 | 81 | Female | No data | No data | Epileptic seizures | Expectant management | No data | No data |

Both in the case presented and in those reviewed, a successful outcome was obtained for patients, with no mortality. This may be caused by a publication bias, since only cases with positive results are available. And also, regarding the different postoperative follow-up evaluations. This is evidenced by the understanding of postoperative success for each author. In some reports without postoperative follow-up, while others only assessing the improvement of clinical symptomatology, and the rest basing success on the imaging follow-up using chest computed tomography, coronary angiography or heart nuclear scintigraphy2,4,7–9 (Table 1).

ConclusionCoronary–pulmonary fistula are unusual. In most cases, they are asymptomatic. However, when a high output is present, they may develop symptoms similar to an acute coronary syndrome. This is mainly due a decrease in coronary flow, which generates a coronary arrest syndrome and areas of myocardial ischemia. Therefore, it is relevant to know this pathology in order to be able to diagnose it and decide the most appropriate management according to its characteristics.

Ethical considerationsThe patient provided informed consent for this report. The article was approved by the institution's review board committee.

FundingNo funding was provided. The project is CAI – from the Avidanti Ibagué clinic.

Conflict of interestThis clinical case report was carried out for academic, descriptive, and self-financed purposes. The authors have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this document.