Systemic-pulmonary fistula remains a critical palliative procedure for congenital heart diseases in pediatric patients but is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.

MethodsThis retrospective cohort study reviewed records of 485 patients undergoing this surgery at a leading tertiary care center from 2010 to 2020.

ResultsThe median age at surgery was 6 months, predominantly for conditions like tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary atresia. Preoperative factors like hemodynamic instability, pre-surgical intubation, and cardiovascular drug use were significant (OR 1.76, 1.65, 1.51 respectively). Thoracotomy was the most common approach (58%), linked to fewer complications (OR 0.37). Complications occurred in 13% of cases, including postoperative bleeding (4.6%) and fistula obstruction (4.3%). Additional interventions (OR 2.25) and reoperations (OR 6.88) correlated with higher complication rates and mortality (9.2%), notably in newborns. Sternotomy had the highest mortality incidence.

ConclusionManaging preoperative risks like hemodynamic instability is crucial for improving outcomes, especially in children under 2 years old. This study underscores the challenges in systemic-pulmonary fistula management and emphasizes the impact of surgical approach on complication rates, advocating for tailored strategies to optimize outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.

La fístula sistémico-pulmonar sigue siendo un procedimiento paliativo crucial para las enfermedades cardiacas congénitas en los pacientes pediátricos, pero está asociada con una considerable morbilidad y mortalidad.

MétodosEste estudio de cohorte retrospectivo revisó los registros de 485 pacientes sometidos a esta cirugía en un centro de atención terciaria líder desde 2010 hasta 2020.

ResultadosLa mediana de edad al momento de la cirugía fue de 6 meses, predominando condiciones como la tetralogía de Fallot y la atresia pulmonar. Factores preoperatorios como la inestabilidad hemodinámica, la intubación prequirúrgica y el uso de medicamentos cardiovasculares fueron significativos (OR: 1,76, 1,65 y 1,51, respectivamente). La toracotomía fue el enfoque más común (58%), asociado con menos complicaciones (OR: 0,37). Las complicaciones ocurrieron en el 13% de los casos, incluyendo sangrado postoperatorio (4,6%) y obstrucción de la fístula (4,3%). Intervenciones adicionales (OR: 2,25) y reintervenciones (OR: 6,88) se correlacionaron con mayores tasas de complicaciones y una mortalidad del 9,2%, especialmente en los recién nacidos. La esternotomía tuvo la mayor incidencia de mortalidad.

ConclusiónEs crucial manejar los riesgos preoperatorios como la inestabilidad hemodinámica para mejorar los resultados, especialmente en los niños menores de 2 años. Este estudio subraya los desafíos en el manejo de la fístula sistémico-pulmonar, y enfatiza el impacto del enfoque quirúrgico en las tasas de complicaciones, abogando por estrategias adaptadas para optimizar los resultados en esta vulnerable población de pacientes.

The early complete repair of cyanotic congenital heart disease has become the preferred treatment option, even in newborns, due to advancements in surgical techniques and intensive postoperative care. However, when total correction is not feasible, palliative procedures remain a viable alternative for cyanotic patients.1,2 Particularly in developing countries, where limited experience and resources are common, the modified Blalock–Taussig (BT) shunt appears to be the preferred approach for infants under one year old with restricted pulmonary blood flow.3 Despite available literature, factors contributing to mortality and morbidity in these cases are not fully characterized.

Reports indicate significant morbidity and mortality associated with the modified BT shunt in neonates. Mortality rates are reported at approximately 15% in patients with a single ventricle and between 3% and 5% in those with biventricular heart disease.4,5 Several risk factors have been identified, including sternotomy, anatomical location of the shunt, use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), body weight less than 3kg, requirement for preoperative ventilation, palliation of single ventricle physiology, pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum, and Ebstein anomaly.

Approximately one-third of deaths occur within the first 24h following surgery.

MethodsStudy designRetrospectively, medical records of all patients undergoing systemic-pulmonary fistula from January 2010 to December 2020 were collected at a specialized cardiovascular center. Patients were identified from the department's database. The study encompassed all patients under 18 years old who underwent systemic-pulmonary fistula. Patients with incomplete or insufficient data were excluded. Ethics and Research Committee approval was obtained prior to the study.

Outcome definitions- -

Complications: Transsurgical and post-surgical complications were considered. Transsurgical complications included arterial hypotension, cardiorespiratory arrest, desaturation, low cardiac output, transsurgical bleeding, vascular injury, and fistula obstruction. Post-surgical complications were categorized as pulmonary, infectious, or renal.

- -

Mortality: Evaluated through hospital records, mortality was documented during hospitalization (in-hospital mortality) with death certificates specifying causes such as cardiogenic shock, septic shock, hemorrhagic shock, or mixed shock.

- -

Sociodemographic variables: Age group and sex.

- -

Clinical variables: Primary diagnosis and anthropometric data.

- -

Pre-surgical evaluation: Clinical condition, pre-surgical intubation, hypoxic crises, hemodynamic instability, prior cardiovascular support, and pre-surgical infections.

- -

Surgical variables: Type and size of fistula, surgical approach, concomitant procedures, and complications.

- •

Post-surgical evaluation: Duration of mechanical ventilation, length of post-surgical stay, post-surgical infections, need for renal support, additional interventions and surgeries, reoperations, mortality rates, and causes of mortality.

- •

- -

Qualitative variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies.

- -

Quantitative variables were summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR).

- -

For continuous variables, differences between groups (presence vs. absence of complications or death) were assessed using the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test.

- -

Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests as appropriate.

- -

Univariate factors associated with complications or death were evaluated using binary logistic regression models.

- -

Odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values were reported.

- -

Homoscedasticity and linearity tests were performed for all predictors.

- -

Model diagnostics included evaluation of residual normality.

- -

A significance level of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

- -

All analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.3.1) and RStudio.

In this study, a total of 485 patients underwent systemic-pulmonary fistula surgery. The cohort consisted of 55% males (n=265) and 45% females (n=218), resulting in a male-to-female ratio of 1.2:1. A higher incidence of complications was observed among male patients, totaling 54% (n=152).

The most frequent age group at the time of surgery comprised patients older than 1 month to 2 years, accounting for 49% (n=236), followed by newborns (n=80), with decreasing frequency in older age groups. Infants showed a significant negative association with the occurrence of complications (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.16–0.56, p<0.001). Among those experiencing trans- or postsurgical complications, the highest frequencies were observed in these two age groups, comprising 48% (n=136) and 22% (n=62) respectively.

On average, patients weighed 9kg, and there was a significant negative association between weight and the likelihood of complications (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96–0.99, p<0.001).

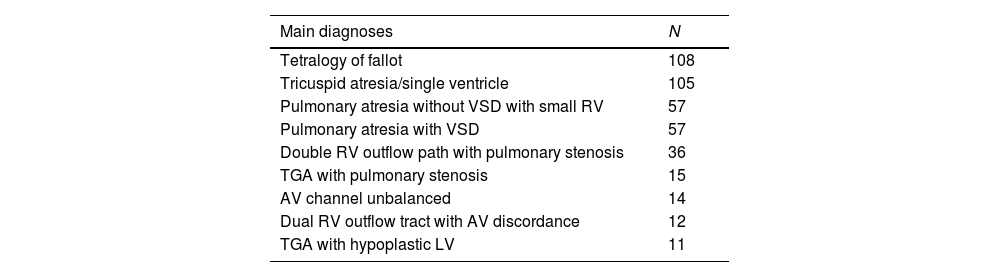

The main diagnoses included congenital heart diseases characterized by reduced pulmonary flow. Among the most frequently reported diagnoses were tetralogy of Fallot, tricuspid atresia/single ventricle, pulmonary atresia, and double outlet right ventricle with pulmonary stenosis, each with its anatomical variations. Tetralogy of Fallot was significantly associated with a lower risk of complications (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.36–0.84, p 0.006) (Table 1).

Main diagnoses.

| Main diagnoses | N |

|---|---|

| Tetralogy of fallot | 108 |

| Tricuspid atresia/single ventricle | 105 |

| Pulmonary atresia without VSD with small RV | 57 |

| Pulmonary atresia with VSD | 57 |

| Double RV outflow path with pulmonary stenosis | 36 |

| TGA with pulmonary stenosis | 15 |

| AV channel unbalanced | 14 |

| Dual RV outflow tract with AV discordance | 12 |

| TGA with hypoplastic LV | 11 |

LV: left ventricle, VSD: ventricular septal defect, RV: right ventricle, TGA: transposition of great arteries, AV: atrioventricular,

Before surgery, 14% of patients experienced hypoxic crises, with 15% of them encountering complications both during and after surgery. Among all patients, 35% required orotracheal intubation prior to surgery, and 38% of these individuals experienced complications during and after surgery. The need for pre-surgical intubation showed a significant positive association with the presence of complications (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.12–2.45, p 0.013). Additionally, pre-surgical hemodynamic instability was significantly associated with complications (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.19–2.62, p 0.005).

Approximately 29% of patients (n=139) began receiving cardiovascular drugs before surgery, which was positively linked with the development of complications (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.00–2.30, p 0.049). The most commonly used inotropic agent was adrenaline, administered to 28% of patients (n=136), followed by milrinone at 2.9% (n=14), among other medications.

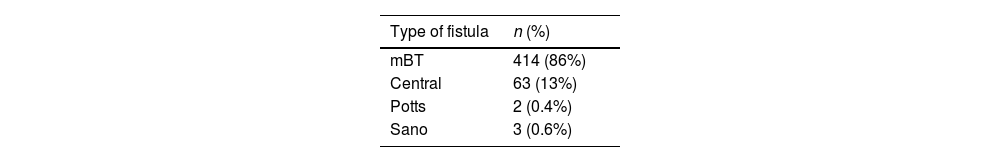

In terms of surgical factors, the modified Blalock–Taussig type of fistula was the most frequently performed, accounting for 86% (n=414) of cases, followed by central fistulas at 13% (n=63). Concerning fistula size, the most common diameter was 5mm, seen in 37% (n=178) of cases, with 4mm following closely at 32%; notably, the latter size was associated with the highest percentage of complications at 39% (n=109) (Table 2).

Thoracotomy was the predominant surgical approach, utilized in 58% (n=279) of cases, and it demonstrated a significant negative association with both trans- and postsurgical complications (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.25–0.54, p<0.001), indicating a lower risk of complications compared to other approaches. Concurrently with systemic-pulmonary fistula surgeries, procedures such as ductus arteriosus ligation, atrioseptectomy, pulmonary artery trunk ligation, and Damus–Kaye–Stansel surgery were frequently performed.

Transsurgical complications affected 52% (n=252) of the patients, with the most common issues being intraoperative arterial hypotension in 33% (n=160), low cardiac output syndrome in 10% (n=49), and desaturation in 7.7% (n=37). Among these 252 patients, 39% (n=186) required additional transsurgical support measures, including volume administration, pharmacological support, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, leaving the sternum open, or placement of a new fistula.

Post-surgical assessment revealed that 91% (n=440) of all patients required mechanical ventilation, with a median duration of 24h. Longer durations of mechanical ventilation showed a significant positive association with the group of patients experiencing complications (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01, p<0.001).

Additionally, the median length of stay in the cardiovascular intensive care unit (ICU) was 4 days, which was also significantly positively associated with the group of patients encountering trans and/or postsurgical complications (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.04–1.11, p<0.001).

Regarding postsurgical complications, they affected 13% (n=62) of the patients. The most common complications included postsurgical bleeding in 4.6% (n=22), pulmonary systemic fistula obstruction in 4.3% (n=21), heart failure in 1.4% (n=7), and anastomotic stenosis in 0.6% (n=3), among others.

In terms of postsurgical pulmonary complications, they occurred in 18% of patients (n=87), with the most frequent being pleural effusion in 9.3% (n=45), pneumothorax in 2.3% (n=11), and postsurgical atelectasis in 2.1% (n=10). Sepsis, as a postsurgical infectious complication, affected 16% of patients (n=75), followed by pneumonia in 0.8% (n=4).

The presence of cardiac complications showed a significant positive association with the risk of overall complications or death (OR 4.81, 95% CI 3.24–7.23, p<0.001).

Out of all patients included in the study, 13.5% (n=65) underwent catheterization, either for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. Among these, 9.5% (n=46) required a therapeutic interventional procedure. The most frequent therapeutic procedures included angioplasty with stent during systemic-pulmonary fistula surgery, performed in 3.3% of the total (n=16), followed by atrioseptostomy in 2.1% (n=10), and angioplasty with stent in the left branch of the pulmonary artery in 2.1% (n=10), among others.

Performing post-surgical catheterization showed a significant positive association with complications and mortality (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.27–4.21, p 0.008). Additionally, undergoing an additional interventional procedure was positively associated with post-surgical complications and increased mortality (OR 3.49, 95% CI 1.67–8.22, p 0.002). Specifically, the need for angioplasty with stent during pulmonary systemic fistula surgery was positively associated with complications and post-surgical mortality (OR 4.85, 95% CI 1.34–31.1, p 0.038).

Out of the entire cohort studied, 17% (n=82) of patients underwent a second surgery. This included 5.4% (n=26) who required a second modified Blalock–Taussig pulmonary systemic fistula, and in other cases, reoperation was necessitated due to complications such as unusually severe bleeding, occurring in 5% of all patients (n=24).

Reoperation was significantly associated with an increased risk of complications (OR 6.88, 95% CI 3.52–15.1, p<0.001). Similarly, the need for a new pulmonary systemic fistula was positively associated with both complications and significant mortality (OR 8.63, 95% CI 2.52–54.1, p 0.004) (Table 3).

Surgical characteristics, perioperatory variables and outcomes.

| Outcomes | Univariable association | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Totaln=485a | Presentn=194a | Absentn=291a | p-Valueb | ORc | 95% CIc | p-Value |

| Pre-surgical evaluation | |||||||

| Pre-Qx intubation, n (%) | 167 (34%) | 54 (28%) | 113 (39%) | 0.013 | 1.65 | 1.12, 2.45 | 0.013 |

| Pre-Qx hypoxia crisis, n (%) | 70 (14%) | 26 (13%) | 44 (15%) | 0.6 | 1.15 | 0.69, 1.96 | 0.60 |

| Pre-Qx hemodynamic instability, n (%) | 166 (34%) | 52 (27%) | 114 (39%) | 0.005 | 1.76 | 1.19, 2.62 | 0.005 |

| Pre-Qx amines, n (%) | 139 (29%) | 46 (24%) | 93 (32%) | 0.049 | 1.51 | 1.00, 2.30 | 0.050 |

| Pre-Qx infection, n (%) | 9 (1.9%) | 1 (0.5%) | 8 (2.8%) | 0.093 | 5.44 | 0.99, 101 | 0.11 |

| Concomitant surgeries | |||||||

| Damus Kaye Stansel, n (%) | 9 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (3.1%) | 0.013 | 3,961,049 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| Atrioseptostomy, n (%) | 15 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (5.2%) | 0.001 | 11,001,319 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| Extended coartectomy, n (%) | 4 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.4%) | 0.2 | 3,892,041 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| PA trunk ligation, n (%) | 10 (2.1%) | 3 (1.5%) | 7 (2.4%) | 0.7 | 1.57 | 0.43, 7.35 | 0.52 |

| PD ligature, n (%) | 21 (4.3%) | 3 (1.5%) | 18 (6.2%) | 0.014 | 4.20 | 1.40, 18.1 | 0.023 |

| Ligation collaterals, n (%) | 4 (0.8%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.7 | 2.01 | 0.26, 40.8 | 0.55 |

| PA branch plasty, n (%) | 5 (1.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (1.4%) | 0.7 | 2.69 | 0.39, 52.8 | 0.38 |

| Lung bandage, n (%) | 15 (3.1%) | 6 (3.1%) | 9 (3.1%) | >0.9 | 1.00 | 0.35, 3.03 | >0.99 |

| Glenn decommissioning, n (%) | 5 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (1.7%) | 0.2 | 3,905,649 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| Norwood, n (%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.3 | 1,426,830 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| Approach route, thoracotomy, n (%) | 279 (58%) | 139 (72%) | 140 (48%) | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.25, 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Post-surgical evaluation | |||||||

| ICU ventilation, n (%) | 442 (91%) | 183 (94%) | 259 (89%) | 0.043 | 0.49 | 0.23, 0.96 | 0.047 |

| Mechanical ventilation hours | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.01 | <0.001 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 24 (8, 90) | 16 (6, 45) | 38 (12, 131) | ||||

| Range | 0, 836 | 0, 576 | 0, 836 | ||||

| ICU time (days) | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.04, 1.11 | <0.001 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (2, 8) | 3 (2, 5) | 5 (2, 10) | ||||

| Range | 1, 57 | 1, 57 | 1, 35 | ||||

| Cardiac complication, n (%) | 316 (65%) | 86 (44%) | 230 (79%) | <0.001 | 4.81 | 3.24, 7.23 | <0.001 |

| Post-Qx pulmonary complications, n (%) | 87 (18%) | 23 (12%) | 64 (22%) | 0.004 | 2.10 | 1.27, 3.57 | 0.005 |

| Post-Qx infection, n (%) | 0.003 | ||||||

| Sepsis | 75 (16%) | 17 (8.9%) | 58 (20%) | 2.59 | 1.49, 4.73 | 0.001 | |

| Pneumonia | 4 (0.8%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.0%) | 2.28 | 0.29, 46.3 | 0.48 | |

| Post-Qx kidney support, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 51 (11%) | 6 (3.1%) | 45 (15%) | 5.76 | 2.59, 15.3 | <0.001 | |

| Hemofiltration | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 597,943 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 | |

| Additional interventional procedures | |||||||

| Post-Qx catheterization, n (%) | 65 (13%) | 16 (8.2%) | 49 (17%) | 0.007 | 2.25 | 1.27, 4.21 | 0.008 |

| Additional interventional procedure, n (%) | 46 (9.5%) | 8 (4.1%) | 38 (13%) | 0.001 | 3.49 | 1.67, 8.22 | 0.002 |

| Angioplasty stent SPF, n (%) | 16 (3.3%) | 2 (1.0%) | 14 (4.8%) | 0.022 | 4.85 | 1.34, 31.1 | 0.038 |

| Atrioseptostomy, n (%) | 10 (2.1%) | 3 (1.5%) | 7 (2.4%) | 0.7 | 1.57 | 0.43, 7.35 | 0.52 |

| Pulmonary artery branch stent angioplasty, n (%) | 10 (2.1%) | 3 (1.5%) | 7 (2.4%) | 0.7 | 1.57 | 0.43, 7.35 | 0.52 |

| Collateral embolization, n (%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.3 | 1,426,830 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| SPF embolization, n (%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.3 | 1,426,830 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| Ductus arteriosus stent embolization, n (%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.3 | 1,426,830 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| Reoperations | |||||||

| Reoperation, n (%) | 82 (17%) | 9 (4.6%) | 73 (25%) | <0.001 | 6.88 | 3.52, 15.1 | <0.001 |

| Sternal closure, n (%) | 8 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (2.7%) | 0.024 | 3,947,052 | 0.00, NA | 0.98 |

| Starnes surgery, n (%) | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | >0.9 | 0.67 | 0.03, 16.9 | 0.77 |

| Total correction, n (%) | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | >0.9 | 0.67 | 0.03, 16.9 | 0.77 |

| Jatene surgery, n (%) | 4 (0.8%) | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0.7 | 2.01 | 0.26, 40.8 | 0.55 |

| Ligation PD, n (%) | 3 (0.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (0.7%) | >0.9 | 1.34 | 0.13, 28.9 | 0.81 |

| PA trunk ligation, n (%) | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.3%) | >0.9 | 0.67 | 0.03, 16.9 | 0.77 |

| New SPF, n (%) | 26 (5.4%) | 2 (1.0%) | 24 (8.2%) | <0.001 | 8.63 | 2.52, 54.1 | 0.004 |

| Surgical reexploration, n (%) | 24 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (8.2%) | <0.001 | 11,372,150 | 0.00, NA | 0.97 |

Outcomes: intraoperative complications, postoperative complications, and in-hospital mortality.

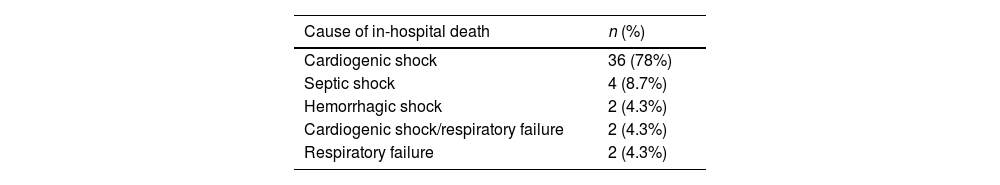

Regarding secondary mortality, it was reported at 9.5%, with a total of 46 deaths recorded. The primary cause of mortality was cardiogenic shock, accounting for 80% (n=36) of cases, followed by septic shock at 9% (n=4), and other forms of shock (Table 4). Mortality occurred more frequently in newborns (under 28 days old) and in those under 2 years old, rather than in older patients, where complete correction is typically pursued if feasible based on individual case assessment.

DiscussionPulmonary systemic fistula surgery is a viable palliative option for managing cyanotic congenital heart disease. Despite its perceived technical simplicity, the procedure is associated with significant postoperative challenges.6 While often considered straightforward, recent reports indicate a mortality rate of 10% or higher,5,7 underscoring its complexity and critical outcomes. In developing countries, where patients often present with restricted pulmonary flow, systemic-pulmonary fistula surgery remains pivotal, necessitating a deeper understanding of factors influencing morbidity and mortality.

At our institution, the procedure is most frequently performed during infancy (1–24 months), followed by newborns, consistent with findings by Singh et al.8 who reported an average age of 10 months. In contrast, Vitanova et al.9 noted a mean age of 98 days, highlighting variability across different studies.

While weight alone did not correlate with mortality in Vitanova's study, a 3mm fistula was associated with increased mortality risk,10 suggesting potential benefits from larger fistula sizes. However, complications were more prevalent with 4mm fistulas in our study.

The decision in our population to perform fistulas of larger diameter (as the only surgical option) was because they were patients who, due to the complexity of their heart condition or their level of severity, were not candidates for corrective surgery or for Glenn and/or Fontan procedures. Therefore, efforts were made to ensure that these fistulas were of the largest possible diameter to promote their durability and limit dysfunction/thrombosis. Hyperflow was documented in 25% of these patients, generally associated with the presence of a patent ductus arteriosus, large collateral vessels, or antegrade flow.

The modified Blalock–Taussig fistula is widely favored,11 corroborating our findings. Traditionally performed via thoracotomy, recent trends favor sternotomy due to lower failure rates and improved pulmonary artery development.12,13 Despite a predominant preference for thoracotomy (57.5%) in our setting, there is a growing shift toward sternotomy (42%).

Our initial approach involves a right or left posterolateral thoracotomy without cardiopulmonary bypass. In cases where a median sternotomy is required, it is performed without cardiopulmonary bypass, except in two instances: one due to severe hemodynamic instability of the patient in the preoperative period, and the other due to the presence of extremely small pulmonary branches.

Complications such as excessive postoperative bleeding and fistula obstruction were notable in our study, differing somewhat from Singh's findings.8 Catheterization rates were higher in our cohort (13.5%) compared to Vitanova's report (9.6%).9

The strategy for bringing patients to intervention in our center includes both preoperative and postoperative approaches. Initially, the patient always undergoes evaluation in the hemodynamic lab prior to surgical correction. In cases of ductal-dependent congenital heart diseases, the aim is to enlarge the ductus. If this is not achievable, an attempt is made to place a stent in the right ventricular outflow tract; if these strategies are not feasible, the patient undergoes surgical creation of a fistula. In the postoperative period, in the presence of clinical deterioration, we perform diagnostic and/or therapeutic interventions, which may include pulmonary branch dilation, fistula intervention, or embolization.

Our reported mortality rate of 9.2% aligns with the broader literature ranging from 2.3% to 16%.4 Studies by Gladman et al. also reported similar mortality rates. Mortality in our study was often associated with factors like low weight, emergency procedures, and pre-surgical hemodynamic instability, echoing findings by Mehmet et al.14,15 Newborns faced the highest mortality rates in our analysis.

Bove et al.10 demonstrated an operative mortality rate of 8.7% in their long-term retrospective analysis of modified Blalock–Taussig fistulas, providing further context to our findings.

LimitationsThis study was conducted at a single center retrospectively, which inherently includes biases associated with record review. Being retrospective and descriptive in nature, it is limited in scope. Nonetheless, it provides a foundational basis for potentially altering the approach to analyzing cases with similar diagnoses and serves as groundwork for future studies to expand upon.

ConclusionsWhile initially considered low-risk, the procedure carries notable risks of morbidity and mortality. Identified risk factors for adverse postoperative outcomes include infancy and neonatal age, small fistula size, preoperative instability, univentricular hearts—particularly pulmonary atresia with intact interventricular septum—and the use of sternotomy during surgery.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Authors’ contributionsLRTC: Original idea, methodology, analysis and writing the original draft, review and editing, JEA: Original idea, methodology, analysis and writing the original draft, review and editing, CCJ: review, BBA: review and editing, GMJA: review and editing, ESR: writing the original draft, review and editing, MSD: writing the original draft, review and editing.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data and material availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [DMS].

To all the staff of the Cardiovascular Critical Care Unit of the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez.