The irruption of endovascular surgery in aortic repair has meant a paradigm shift in the way aortic pathology is approached and occupies a preferential, but not unique, place in the therapeutic algorithms of most modern hospital centres. Its emergence has shaken interprofessional relations in most healthcare settings. The most efficient and smoothest way to incorporate endovascular techniques in different centres is through the creation of an aortic team led by a vascular or cardiovascular surgeon or both. Additionally, the implementation of healthcare policies of centralisation of aortic pathology will contribute to improved outcomes and better use of resources.

However, several limitations remain to be overcome on the road to durable endovascular repair with lower re-intervention rates. There is no doubt that, with the collaboration with bioengineering, the industry involved and the creation of clinical evidence, the future of endovascular techniques, alone or in combination with open surgery, is bright and highly promising for the patients who benefit from them.

La irrupción de la cirugía endovascular en la reparación aórtica ha supuesto un cambio de paradigma en la forma de abordar la patología aórtica y ocupa un lugar preferente, aunque no único, en los algoritmos terapéuticos de la mayoría de los centros hospitalarios modernos. Su aparición ha sacudido las relaciones interprofesionales en la mayoría de los entornos sanitarios. La forma más eficaz y fluida de incorporar las técnicas endovasculares en los diferentes centros es mediante la creación de un equipo de aorta liderado por un cirujano vascular o cardiovascular, o ambos. Además, la implantación de políticas sanitarias de centralización de la patología aórtica contribuirá a mejorar los resultados y a utilizar mejor los recursos.

Sin embargo, aún quedan varias limitaciones por superar en el camino hacia una reparación endovascular duradera con menores tasas de reintervención. No cabe duda de que la colaboración con la bioingeniería, la industria implicada y la creación de evidencias clínicas, el futuro de las técnicas endovasculares, solas o en combinación con la cirugía abierta, es brillante y muy prometedora para los pacientes que se benefician de ellas.

“There is no disease more conducive to clinical humility than aneurysm of the aorta.” Sir William Osler 1849-1919

Endovascular surgery arose out of a need to reduce the mortality and morbidity associated with open or conventional vascular surgical techniques. Endovascular repair of the aorta has followed the same rationale. In fact, its application, exclusively or in combination with conventional surgical techniques, has allowed the successful treatment of patients unsuitable for open surgery.

From an epidemiological point of view, aortic pathology represents a health and economic challenge of the 21st century. Mortality related to aortic pathology, unlike other cardiovascular diseases, has not declined over the past four decades. The global number of deaths caused by aortic aneurysms reached 172,426 in 2019.1 This represents an increase of 82.1% compared to mortality in 1990. The increasing mortality is more evident in developing countries than in developed countries, 0.71 and 0.22 per 100,000 population, respectively.2

In 2018, the global market for the treatment of aortic aneurysms was estimated at 2.3 billion €, estimating an annual growth of 8.6% between 2019 and 2026. This corresponds to a projected growth in the number of annual aortic interventions from 219,664 in 2021 to more than 400,000 in 2030.3

We will now present a personal view of the effects of the advent of endovascular surgery on the therapeutic algorithms for aortic pathology. To do so, we will start with the key historical notes and end with a selection of unmet needs, which still prevent its complete consolidation, and their possible present and future solutions. We will not forget to comment on their impact on interprofessional relations and their mitigation with the creation of aortic team and centralisation.

Brief history of endovascular aortic surgeryThe present situation of endovascular surgery cannot be understood without knowing the historical milestones that marked its origins.

Endovascular surgery, understood as a medical discipline framed within the context of minimally invasive surgery and based on intravascular catheterisation techniques, which uses therapeutic and diagnostic elements introduced through a vascular entry point far away or remote from the vascular pathological process to be treated, has its origins in the catheterisation technique described in 1953 by Seldinger. This technique was later exploited by Dotter in 1964 and Gruntzig in 1974 for therapeutic purposes, thus giving rise to percutaneous transluminal angioplasty as it is known today. These names of radiologists and interventional cardiologists, pioneers of endovascular therapy together with those of Judkins, Porstmann, Zeitler, van Andel, and later Simpson, Palmaz, and many others are the ones that for more than two decades remained ignored by the vascular surgical community in general, dazzled by the new synthetic grafts of polyester and polytetrafluoroethylene, and by the great advances in reconstructive techniques of the aorta and its branches that were offered before their eyes.

It was not until 1988 when, during the annual meeting of the Society for Vascular Surgery in Chicago, the existence of a form of therapy was recognised and coined “The New Endoluminal Vascular Surgery”. Until then, surgeons’ scepticism had overcome their curiosity, which kept them on the side-lines of vascular endoluminal techniques. Meanwhile, radiologists and interventional cardiologists were gaining experience and confidence in them. This is partly the reason for the interdisciplinary struggles when it comes to the now accepted Endovascular Surgery, which some scientific societies and care departments have been quick to add to its original name, inappropriately or undeservedly due to the lack of practical and theoretical knowledge in the field. However, not all surgeons disregarded the potential of catheterisation techniques. This is evidenced by the example of Thomas Fogarty, a vascular surgeon who, having just completed his medical degree, successfully treated an iliac embolism in a young woman for the first time in 1963. He used local anaesthesia and a femoral dissection and arteriotomy to remove the embolism with his own embolectomy catheter, but without fluoroscopic control.4

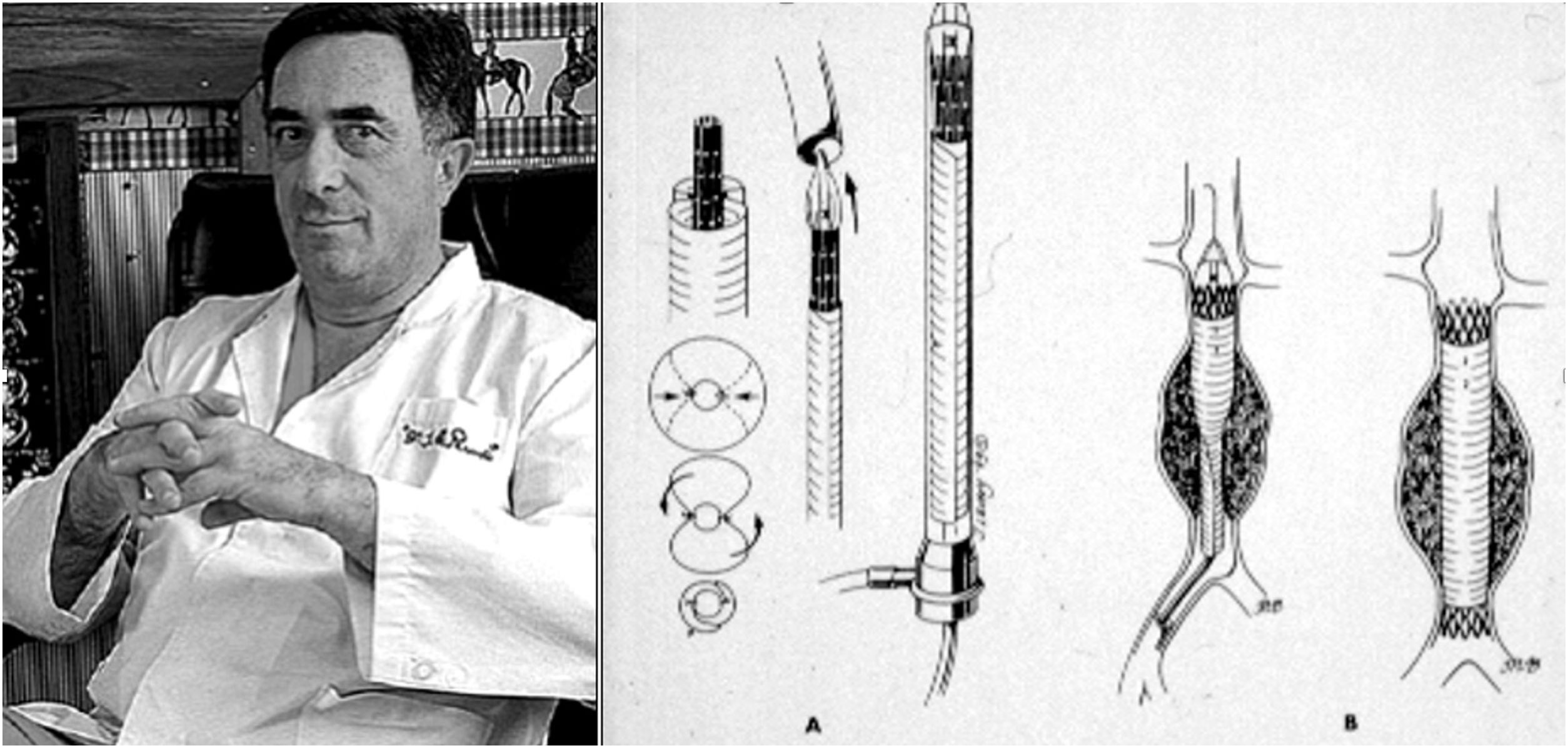

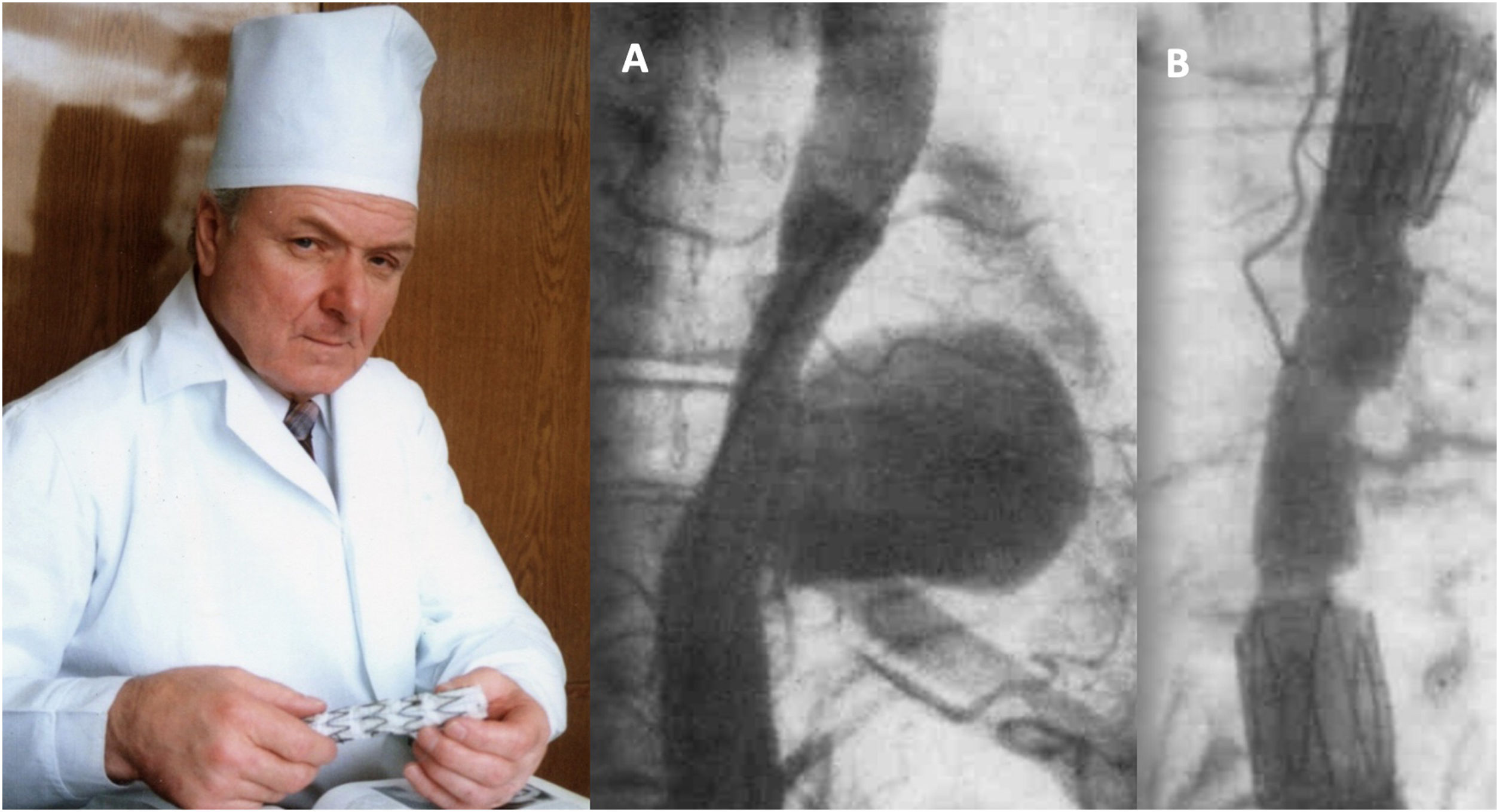

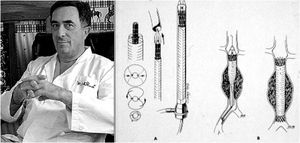

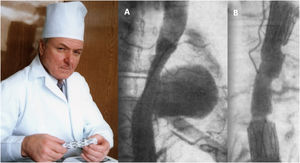

Although vascular surgeon Juan Carlos Parodi (Fig. 1) is credited with the first clinical experience in endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in February 19905 in the city of Buenos Aires, it was in March 1987 when Nicolai Volodos (Fig. 2), Head of Department of Vascular Surgery at the Kharkiv Scientific and Research Institute for General and Emergency Surgery, performed the first endovascular repair of a post-traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the thoracic aorta,6 in Ukraine, which belonged to the Soviet Union at that time. He used a ‘home-made’ endoprosthesis, using Gianturco's stents and covered them with a polyester vascular prosthesis. He then loaded it into a large-bore introducer catheter for endovascular implantation into the descending thoracic aorta under fluroscopic control, thus excluding the extensive pseudoaneurysm. His publication in 1988, in Russian, as expected, did not achieve the international echo that a few years later was monopolised by an American radiologist from Stanford University, Michel Dake. Dake published in 1994 in the New England Journal of Medicine his first series of patients with lesions of the descending thoracic aorta treated with ‘home-made’ stents,7,8 becoming the ‘Western’ pioneer of endovascular treatment of the thoracic aorta.

Juan Carlos Parodi and his scheme of endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm published in Ann Vasc Surg 1991.5

Nicolai Volodos and his first clinical case of endovascular repair of descending thoracic aortic pseudoaneurysm (A) and the immediate angiographic result (B), performed in March 1987.6

Precisely, the possibility of treating aortic aneurysms by means of endovascular techniques burst into the history of Vascular Surgery, which meant a real turning point and reflection. For the first time there was a “widespread fear” among surgeons of “losing” the surgical treatment of one of the emblematic pathologies or “sign of identity” such as the abdominal aortic aneurysm. Suddenly, in some surgeons an unusual interest was awakened to make up for all the precious time lost to be able to recycle themselves and manage to tackle endovascular repair of aneurysms. In 1987, the International Society for Endovascular Surgery, later Specialists (ISES), was founded with a multidisciplinary character, with a small but determined participation of some vascular surgeons from all over the world, at that time not very well regarded by the more classical and traditional colleagues. However, over the years, the society incorporated as members the most significant vascular surgeons from the USA and other countries in the rest of the developed world4. Later, some mixed national Endovascular Surgery projects and societies were created with the participation of surgeons and radiologists, as was and still is the case in Great Britain. In Spain, we still have no official history of collaboration between scientific societies in this sense.

At the professional level, and globally, surgeons adopted three different strategies to adapt to the irruption of endovascular surgery in the different surgical departments and to face up to what has been considered the therapeutic revolution of the aorta.4,9 At the same time, the strategies outlined three coexisting scenarios, tainted, to a greater or lesser degree, by an interprofessional conflict, which still persists in some centres. The conflict stemmed from the interaction of different specialties competing for patients with aortic pathology. On the one hand, the cardiologists, who shared, or not, the aortic pathology patient with the cardiac surgeons. On the other hand, vascular surgeons, experienced in open surgery. But, in addition, diagnostic imaging was carried out by other specialists, the radiologists, who probably shared with their relatives the interventionalists. Clearly, the mastery of catheterisation techniques and their fluoroscopic vision belonged since their inception to other professionals, the radiologists, and interventional cardiologists.

The first scenario was represented by the scepticism or profound rejection on the part of the professionals in charge of patients with aortic pathology. This behaviour did not facilitate the development of new technologies inside and outside their institutions, while at the same time chronicling interprofessional conflict.

The second scenario was marked by the appropriation or “raw” incorporation of the new techniques, following self-taught behaviours, and applying them directly to their own patients. In this situation, interdisciplinary struggles, and conflicts, in addition to hindering interprofessional relations, prevented patients from receiving the best care and delayed the adoption of the new techniques, creating long learning curves, often with adverse results. In addition, it was observed that groups with little or no previous experience in conventional surgical treatment of the thoracic aorta dared to begin their self-taught endovascular experience in this area.

The third strategy was aimed at joining efforts and experiences around the patient. In other words, the creation of multidisciplinary groups led by a clinical manager or coordinator, taking aortic pathology as a clinical process, including diagnosis, patient selection, treatment selection, the procedure itself, and immediate and long-term follow-up. All these sections are of equal relevance to ensure technical and clinical success, and must therefore be applied with equal interest, dedication and professionalism. The latter solution facilitated the interprofessional relationship, smoothed learning curves and allowed for better results. This option was recommended by the health authorities, by the pioneering groups and by the companies that manufactured and marketed aortic endoprostheses. This was the option that our institution adopted, which allowed our centre to be a pioneer in endovascular treatment of the aorta in our country. This was the origin of our current Aorta Unit based on the concept of the aortic team.

Aortic team and centralizationAn interesting consensus document on the treatment of the thoracic aorta involving the arch, published jointly in 2019 by the European Association of Cardiac and thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) defines the aortic team as “as one that is led by members from cardiac and vascular surgery in collaboration with anaesthesiology, cardiology, radiology, and genetics”.10 In it, the leadership of these multidisciplinary groups corresponds to the vascular and/or cardiac surgeon, due to his better knowledge of the pathology and the different therapeutic alternatives. This approach should not be limited to aortic arch pathology. As recent international guidelines argue, it is advisable to consider it for the rest of the aorta.11–13

Our Aorta Unit meets weekly to discuss each and every case with aortic pathology. Different specialties are constantly involved in the unit. Vascular Surgery, Cardiac Surgery, Anaesthesiology, Vascular Radiology, Cardiology, Gerontology, Operating Room, Ward and ICU Nursing. When cases require it, other related specialists such as pneumologists, psychiatrists or others are invited. Decisions are systematically shared with patients and their relatives.

However, as the guidelines also state, this concept must be accompanied by another organisational change, namely the centralisation of these pathologies. The aim of centralisation is to accumulate the volume of experience and thus optimise results. In our autonomous community, centralisation of aortic treatment was implemented in 2014. In less than 3 years we were already able to confirm that clinical outcomes improved significantly after the application of centralisation in abdominal aortic repair.14

We are aware of the drawbacks and potential difficulties associated with both concepts, aortic team and centralisation, and that these will vary in each hospital and healthcare setting. However, in our experience and that of most of the pioneering groups, both are essential to achieve the best clinical results, while maintaining the best interprofessional relations. Additionally, this approach can better contribute to training, research and development of the different techniques and, at the same time, generate the necessary and never sufficient scientific evidence. However, some of the collateral effects, such as the loss of aortic surgery in peripheral services, can be mitigated by the collaborative network and the transit of interested professionals.

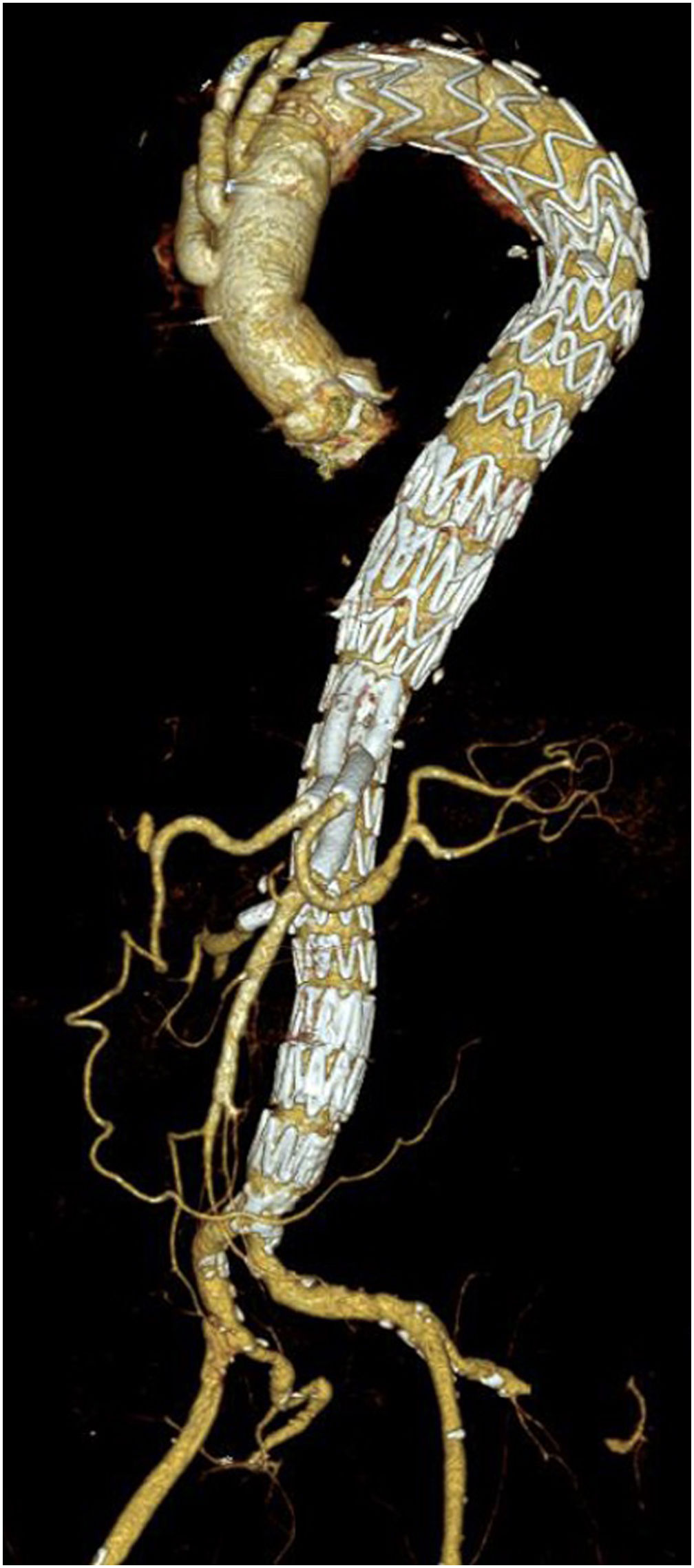

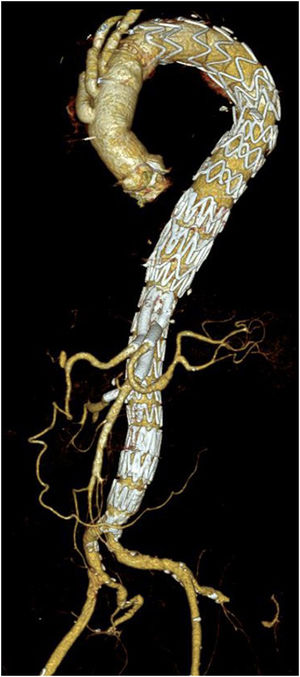

Unmet needsOver the past three decades, endovascular surgery of the aorta has grown in quantity and quality, aided by technological improvements in diagnostics, imaging, navigation and in the design of the stents themselves and their delivery mechanisms. It is now possible to offer endovascular treatment for most aortic pathologies, from the aortic valve to the iliac arteries (Figs. 3 and 4). Moreover, most part of the endovascular procedures are performed by percutaneous approach with closure systems. That is the case, for instance, in our centre with less than 2% of complication rate at the level of the vascular access. Thus, it has become the most widespread and preferred method of aortic repair by most specialists and patients. However, there are still some shortcomings to be resolved that partly overshadow its brilliant emergence in the aortic therapeutic armamentarium. The most relevant are related to the durability of treatments and the creation of validated scientific evidence.

Poor durability leads to a high percentage of re-interventions. At five year follow-up, the cumulative re-intervention rate after endovascular thoracic or abdominal aorta repair is estimated as higher as 25%.10–13 Despite of most of them can be satisfactorily resolved with endovascular methods, such as placement of additional endograft components or embolisation techniques, require lifelong follow-up and additional avoidable health care costs. But, what does the durability of endovascular procedures depend on? It does not only depend on the quality of the different devices implanted. The indication and proper use of the devices, within the manufacturers’ instructions for use, are factors that, like skill and precision, depend on the treating team. Also, for better durability, the follow-up of treated patients should be mandatory and protocolised, as advised by all international guidelines.10–13 The experience of the teams as well as the constant improvement of the implanted materials are and will be crucial to optimise the results in terms of durability.

In addition, new technological innovations, such as artificial intelligence, will help us to detect individualised risks, both clinical and anatomical, in the selection of patients, in the repair procedures themselves and in the follow-up of endovascular implants and non-interventional aortic pathologies.15 One of the unresolved needs, in terms of durability, which generates concern and controversy in its treatment, is the presence of endoleaks, especially type II, representing an average prevalence of 20% at 5 years of follow-up. These, implicit in endovascular treatment of the aorta, are considered a real Achilles heel for the endovascular technique. We must improve early detection of those cases requiring adjuvant action such as preventive embolisation. Possibly, also with the help of artificial intelligence, the incidence of this implicit but not always benign complication can be reduced.16

There is certainly a continuing need for safe and effective endovascular repair of anatomies that are currently considered marginal. We are referring to the ascending aorta or pathology associated with connective tissue diseases. It is in these types of clinical–morphological circumstances that interdisciplinary collaboration must be well defined and protocolised. This is where the idea of the aortic team makes the most sense. Similarly, combined or hybrid repair is and will be indispensable for decades to come. Individualised solutions make it essential to consider combined or hybrid approaches and treatments in selected cases. For instance, ascending and arch replacement with frozen elephant trunk in combination with a subsequent endovascular repair of the descending thoracic aorta is a common solution today in our centre.

One of the needs that has been little discussed in the literature so far, but which is of increasing concern to more and more researchers, is related to the lack of substantial innovation in the design of the stents themselves. Specifically, we refer to the material components of the different stents available commercially so far. All of them combine metal alloy stents with polytetrafluoroethylene or polyester fabrics whose technologies are very “classic”, both in open and endovascular surgery. Although they have proven usefulness, the low compliance of current prostheses and stents, they impart an aortic stiffness that has been linked to serious adverse cardiac effects. This effect is of relevance for endoprostheses when applied to the thoracic aorta, where aortic biomechanics would require materials more compatible with the biomechanical behaviour of the aortic tissue itself.1–19 Therefore, this is another aspect to be improved in future designs of thoracic devices, especially for those pathologies related to acute aortic syndrome, aortic trauma, and connective tissue disorders. Soon, new biological and/or pharmaceutical adjuvants may even be combined with new endografts to prevent aortic wall degeneration or induce tissue regeneration. That is the case of new investigational approaches like the pharmaceutical stabilisation of small abdominal aneurysms with Pentagalloyl Glucose,20 or new biocompatible and bioabsorbable devices like Aortyx patch.21

Stroke is also a relevant complication that limits the success of endovascular treatment of the aorta, especially at the proximal thoracic aorta where can reach up to 25% of incidence.22 Although we have identified risk factors such as “dirty” aorta or excessive manipulation of the arch and its branches by guidewires and catheters, there is still room for improvement in perioperative stroke rates.22

One relevant and inherent limitation of endovascular techniques is associated with the indispensable use of X-rays. It is clear to everyone that this is not good for patients or for the professionals who use them. For this reason, in addition to improving and perfecting the performance of X-ray machines with fusion capabilities,23 there are other initiatives such as the use of other fibre-optic navigation methods like FORS,24 with the combination of intravascular ultrasound,25 or even with the participation of robotics.26

As mentioned above, it is necessary to create clinical evidence, whatever its grade, to consolidate the different technological advances and different endovascular techniques applied in aortic repair. It will not be easy to generate grade A evidence because of the difficulty of conducting prospective, randomised studies for various reasons, especially economic ones. However, other forms of evidence, like meta-analysis of well-designed prospective registries or randomised registries,27 should be constructed to facilitate the monitoring of the benefits of endovascular surgery in aortic pathology. This will make it easier to meet the increasingly demanding requirements of health authorities through regulatory agencies.28

Finally, it is necessary to reflect on the education and training of our future vascular surgeons. Although the current trend is marked by a predominance of endovascular techniques, we should not forget traditional or open surgery, since not all cases cannot be solved with endovascular surgery. That is why teaching services are concerned with how to transmit knowledge and skills to our residents in open surgery. Simulation, experiences in centres of expertise and/or, once again, centralisation can respond to this increasingly obvious problem.

One final issue must be addressed, relating to the pressure exerted by the industry which markets stents and all the adjuvant technologies. The best recommendation is to resist and follow the existing clinical evidence and built up the new one. For this it is very useful to work from a multidisciplinary aorta unit and with strict independent and transparent economic-financial control.

SummaryThe irruption of endovascular surgery in aortic repair has meant a paradigm shift in the way aortic pathology is approached and occupies a preferential, but not unique, place in the therapeutic algorithms of most modern hospital centres. Its emergence has shaken interprofessional relations in most healthcare settings. The most efficient and smoothest way to incorporate endovascular techniques in different centres is through the creation of an aortic team led by a vascular or cardiovascular surgeon or both. Additionally, the implementation of healthcare policies of centralisation of aortic pathology will contribute to improved outcomes and better use of resources.

However, several limitations remain to be overcome on the road to durable endovascular repair with lower re-intervention rates. There is no doubt that, with the collaboration with bioengineering, the industry involved and the creation of clinical evidence, the future of endovascular techniques, alone or in combination with open surgery, is bright and highly promising for the patients who benefit from them.

Finally, as a general recommendation, do not forget the wise and prudent words of Sir Wiliam Osler: “There is no disease more conductive to clinical humility than aneurysm of the aorta.” And extend them to all aortic pathology.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares that he has potential conflicts of interest due to his relationship as consultant or advisor with the following companies:

- •

Terumo Aortic

- •

Medtronic

- •

iVascular

- •

W.L. Gore & Associates

- •

Aortyx (Founder and Stockholder)