Diverticular disease, and the diverticulitis, the main complication of it, are widely studied diseases with multiple chronic cases reported in the literature, but there are no atypical presentations with extra-abdominal symptoms coupled with seemingly unrelated entities, such as necrotising fasciitis.

Clinical caseFemale 52 years old, was admitted to the emergency department with back pain of 22 days duration. History of importance: Chronic use of benzodiazepines intramuscularly. Physical examination revealed the presence of a gluteal abscess in right pelvic limb with discoloration, as well as peri-lesional cellulitis and crepitus that stretches across the back of the limb. Fasciotomy was performed with debridement of necrotic tissue. Progression was torpid with crackling in abdomen. Computed tomography showed free air in the cavity, and on being surgically explored was found to be complicated diverticular disease.

DiscussionIt is unusual for complicated diverticular disease to present with symptoms extra-peritoneal (<2%) and even more so that a diverticulitis is due to necrotising fasciitis (<1%). The absence of peritoneal manifestations delayed the timely diagnosis, which was evident with the crackling of the abdomen and abdominal computed tomography scan showing the parietal gaseous process.

ConclusionAll necrotising fasciitis needs an abdominal computed tomography scan to look for abdominal diseases (in this case diverticulitis), as their overlapping presentation delays the diagnosis and consequently the treatment, making a fatal outcome inevitable.

La diverticulitis como principal complicación de la enfermedad diverticular representa una enfermedad ampliamente estudiada y con múltiples casos crónicos reportados en la bibliografía. No es así en el caso de las presentaciones atípicas con sintomatología extraabdominal, con entidades aparentemente sin relación, tales como la fascitis necrosante.

Caso clínicoPaciente mujer de 52 años de edad, que ingresó al servicio de urgencias con lumbalgia de 22 días de evolución y con el antecedente de uso crónico de benzodiacepinas intramuscular. A la exploración física se detectó la presencia de absceso glúteo y en extremidad pélvica derecha, con cambios de coloración perilesional, celulitis y crepitación que se extendía a toda la parte posterior de dicha extremidad. Se realizó fasciotomía con desbridamiento de tejido desvitalizado. Se presentó evolución tórpida con crepitación en abdomen, razón por la cual se le realizó tomografía axial computada, con la que se documentó aire libre en cavidad abdominal, por lo que se exploró quirúrgicamente, con el hallazgo de enfermedad diverticular complicada.

DiscusiónEs inusual que una enfermedad diverticular complicada se presente con un cuadro extraperitoneal (< 2%) y, más aún, que una diverticulitis sea causa de una fascitis necrosante (< 1%). La ausencia de manifestaciones peritoneales, con enmascaramiento del sitio primario de infección, el cual se hizo evidente con la crepitación del abdomen y con una tomografía axial computada abdominal que mostraba el proceso gaseoso parietal.

ConclusiónToda fascitis necrosante amerita una tomografía abdominal con búsqueda intencionada de enfermedad abdominal, en este caso una diverticulitis, ya que una presentación solapada puede retrasar el oportuno y adecuado tratamiento, haciendo inevitable un resultado fatal.

A diverticulum is a pouch of mucosa that forms in the muscular wall of the intestine. The presence of diverticula with no symptoms is called diverticulosis. Once symptoms appear it is considered to be a diverticular disease. Diverticulitis is the complication with the greatest risk in this disease. Epidemiologically, prevalence varies with age, with ≤ 5% of cases presenting in patients aged between 40 and 50, in >30% of those aged between 51and 60 and in ≥65% of those aged between 60 and 80.1 A simple diverticular disease is that which develops minimal symptoms such as constipation, abdominal distension and pain, which is present in 75% of cases. It is only complicated in 25% of all cases and may lead to abscesses, fistulae, obstruction, peritonitis and sepsis.2

Fistulae are the main complication and clinical signs will depend on the extent or rupture of a diverticular or phlegmon abscess within the anatomical structures or nearby organs. Both spontaneous incidence and that occurring as a result of a surgical procedure is ∼12%,3 with the possible participation of any pelvic structure, such as the bladder, vagina, uterus and other segments of the colon or ileum, and also the anterior abdominal wall. However, on rare occasions (<2%), extraperitoneal symptoms present.4 Moreover, and with no apparent relationship, there is another disease known as necrotising fasciitis, conceptualised as a rapidly advancing infection, which affects the skin, subcutaneous cell tissue, superficial fascia and occasionally the deep tissue planes, such as the deep fascia. This condition may lead to tissue necrosis and severe systemic toxicity.5

Clinical caseA 52 year old female patient, who was admitted to the Emergency service of the Dr. Valentín Gómez Farías hospital due to a 22-day history of back pain. The only history of importance was chronic use of benzodiacepines intramuscularly.

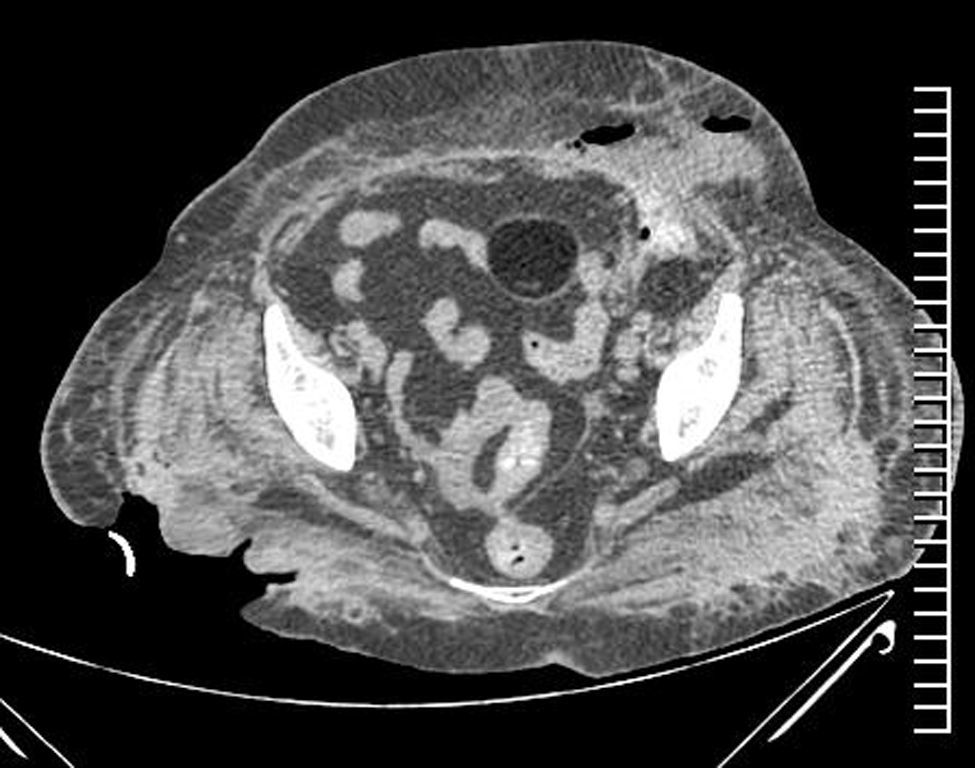

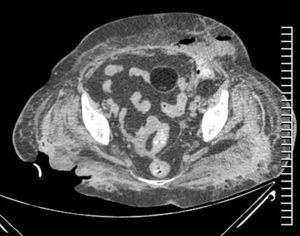

The abdomen was free from signs on physical examination but the latter revealed the presence of a gluteal abscess in right pelvic limb with signs of necrotising fasciitis characterised by discoloration, as well as peri-lesional cellulitis and crepitus that stretched across the back of the right pelvic limb, and seemingly limited by the popliteal fossa. Laboratory findings showed leukocytosis of 33,390mm3, 84% neutrophils and 49% bands. Based on the reported findings and due to the need for surgical intervention, fasciotomy was performed with debridement of necrotic tissue up to the popliteal gap (Fig. 1). Due to unstable haemodynamic conditions secondary to the inflammatory systemic response from a broad infectious process presented by the patient, she was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit and after 2 days presented with torpid evolution, progressive deterioration and septic shock. Examination revealed structural changes in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen with crackling, hyperaemia and hyperthermia (Fig. 2). An axial computed tomography was therefore performed, which reported free air in the abdominal cavity (Fig. 3). Surgical exploration ensued and surgical findings reported were: presence of abundant faecal material in subcutaneous cell tissue, abdominal cavity contaminated with faecal material, descending colon coterminous to abdominal wall, with perforated diverticulum draining into the cavity and subcutaneous cell tissue. As a result, an exhaustive lavage of the cavity was performed, as was colostomy and the Hartman procedure, and Vacuum Assisted Closure (VAC) ABThera™ (Fig. 4). Clinical management was continued with intensive care and successive replacements of the VAC (every 72h). After the fifth replacement the cavity was clean and wall closure was performed.

Slight ventilator and haemodynamic improvement followed with the patient being admitted to the intermediate care unit isolated ward, on the general surgical floor. A few hours after admittance, bleeding of the digestive tube, secondary to coagulopathy was detected, and therapy with blood products was initiated, with no improvement. The patient presented with cardiorespiratory arrest which responded to advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation. However, despite this management a new episode followed to which no response was made by the patient, and this resulted in a fatal outcome.

DiscussionIt is unusual (<2% of cases) for a complicated diverticular disease to present with extraperitoneal symptoms, and even more so for a diverticulitis to be the cause of a necrotising fasciitis (<1%).4 Necrotising fasciitis is a serious and often fatal condition. It is a rapidly advancing infection which generally affects genital fascia, often with a polymicrobian aetiology.5 Mortality occurs in 30–70% of cases, with greater risk in patients with a compromised immune system caused by: diabetes, advanced age, malnutrition and obesity.6 However, necrotising fasciitis as a consequence of intestinal perforation is a rare but potentially lethal condition, which requires prompt surgical intervention.7,8

Previous reports have documented the presence of abscesses in the retroperitoneal space, which may be the consequence of diverticulitis or acute complicated appendicitis with posterior formation of fistulae to different anatomical regions, even those far away from the peritoneal cavity, eventually leading to extraperitoneal symptoms.9

The absence of peritoneal symptoms delays correct diagnosis, until the presence of subcutaneous gas or emphysema presents. Whether or not this is an expression of necrotising fasciitis it may be associated with certain intraabdominal processes and more specifically with diverticulitis, an association which has been reported in different international studies.10,11 Subcutaneous l emphysema in soft tissues, both in the abdomen or the lower limb, maybe secondary to the movement of gas through a passage of least resistance, compared with the peritoneal cavity and secondly, by the presence of microorganisms forming gas.11,12 Free air travels from the abdomen to the thigh through different routes11: (1) From a deep route of the inguinal ligament through the psoas sheath, femoral sheath and femoral canal. (2) Through the fibrous canals along the sacrosciatic groove through the obturator foramen. (3) From the abdominal wall, following the subcutaneous route. (4) Directly through the pelvic floor. (5) Through general secondary septicaemia cellulitis.

The mortality rate caused by hip and thigh emphysema secondary to the perforation of the gastrointestinal tract is between 34% and 93% of cases.11–14 In patients treated with local draining alone, the mortality rate rises to 93%, whilst in patients undergoing extensive surgery the rate may drop to 34%.13 It is therefore obvious that both the local process and the intra-abdominal lesion may be treated with surgery.15 In cases of perforation of intraperitoneal structures, such as sigmoid or descending colon (as occurred in our case), the gas appears to penetrate the thigh through the psoas and iliac muscles, with secondary subcutaneous rupture.

Necrotising fasciitis of the abdominal wall is a rare condition and is therefore not associated with complicated diverticular disease. In fact, there are few reviews in the medical literature where these 2 conditions are associated.

Our clinical case establishes an unusual presentation with extraperitoneal symptoms, and a diagnosis overlapping with a secondary condition, which was made obvious by the decolouration and crackling of the wall. Ancillary studies were later performed, including computed axial tomography of the abdomen, which showed the parietal gaseous process. The latter led us to review the literature to establish the usefulness of this imaging tool. In 1961 Rafailidis et al.16 demonstrated that the presence of superficial gas in the abdominal wall or in the thigh may be secondary to intraabdominal events or to a retroperitoneal abscess. This association was established for the first time by Rodlaha in 1926, in a patient with subcutaneous emphysema, with a sub-diaphragmatic abscess caused by gastric ulcer perforation. Many reports followed his observation during later years without determining a diagnostic tool which was not invasive. In a recently published study the role of computed tomography of multi-detectors in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal perforation was assessed and the authors reviewed the tomography examinations in search of gastrointestinal perforation which later showed up surgically. The signs of perforation included: the presence of free air, the leakage of oral contrast material, a swollen intestinal wall, wall discontinuity, the formation of abscesses, the presence of free fluid formations, and the presence of a phlegmon.15–17 It was therefore concluded that the perforation site could be correctly confirmed through the use of tomography, which will depend on the part of the perforated gastrointestinal system: 85.7% in patients with gastroduodenal perforation, 85.7% in patients with perforation of the small intestine, 69.2% of patients with perforation of the colon, 100% of patients with perforation of the rectum and 90.9% of patients with perforation of the appendix, establishing an overall percentage correct diagnosis of 82.9%.18 However, the main primary diagnostic tool continues to be surgical exploration, which is undoubtedly an invasive procedure and which often does not offer any certainty.7

Lastly, no discussion regarding the usefulness of the VAC therapy system has ensured, to confirm its efficacy in controlling and limiting the infectious process in both the abdominal cavity and soft tissues.19

ConclusionProgressive follow-up should be established for all patients who present a necrotising fasciitis, since often due to the background and the way in which symptoms began, no ancillary studies are made, whilst the underlying process is ignored, as occurred in our clinical case. Suspected diagnosis needs to be present, followed by prompt, aggressive surgical management, since an overlapping presentation may delay accurate and appropriate treatment, making a fatal outcome inevitable.

To conclude, every patient with necrotising fasciitis should be broadly assessed, with the inclusion of an abdominal tomography in search of suspected abdominal disease, in this case diverticulitis, and this should be the definitive tool for identifying a possible underlying abdominal process.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingNo sponsorship was received for the production of this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gallegos-Sierra C, Gutiérrez-Alfaro C, Evaristo-Méndez G. Enfermedad diverticular complicada iniciada como fascitis necrosante de miembro pélvico. Reporte de caso. Cir Cir. 2017;85:240–244.