The purpose of the diagnostic evaluation of adnexal tumours is to exclude the possibility of malignancy. The malignancy risk index II identifies patients at high risk for ovarian cancer. The cut-off value is greater than 200.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of malignancy risk index II in post-menopausal women with adnexal tumours in relation to the histopathological results.

Materials and methodsA total of 138 women with an adnexal mass were studied. The malignancy risk index II was determined in all of them. They were divided into two groups according to the histopathology results; 69 patients with benign tumours and 69 patients with malignant tumours. A diagnostic test type analysis was performed with respect to the results of malignancy risk index II≤200 or greater than this.

ResultsThe percentages and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. The accuracy was 81.8% (75.5–88.3), sensitivity 76.8% (66.9–86.7), specificity 87% (79.1–94.9), with a positive predictive value of 85.5% (76.7–94.3), and a negative predictive value of 78.9% (69.7–88.1). The positive likelihood ratio was 590, and the negative likelihood ratio was 0.266.

ConclusionsThe malignancy risk index II has good performance in the proper classification of post-menopausal women with adnexal masses, both benign and malignant, with an accuracy of 81.8%.

La finalidad en la evaluación diagnóstica de los tumores anexiales es excluir la posibilidad de que se trate de un proceso maligno. El índice de riesgo de malignidad II, identifica a pacientes con alto riesgo de presentar cáncer de ovario. Su valor de corte es mayor de 200.

ObjetivoEvaluar la exactitud diagnóstica del índice de riesgo de malignidad II en mujeres posmenopáusicas con tumor anexial.

Material y métodosSe estudiaron 138 mujeres con diagnóstico de masa anexial. A cada una de ellas se le determinó el índice de riesgo de malignidad. Se dividieron en dos grupos de acuerdo a los resultados de histopatología; 69 pacientes con tumores benignos y 69 pacientes con tumores malignos. Se realizó un análisis tipo prueba diagnóstica con respecto a los resultados del índice de riesgo de malignidad II, en ≤ 200 o mayor a este.

ResultadosLos siguientes porcentajes e intervalos de confianza del 95% fueron calculados, exactitud 81.8% (75.5–88.3), sensibilidad 76.6% (66.9–86.7), especificidad 87% (79.1–94.9), valor predictivo positivo 85.5% (76.7–94.3), valor predictivo negativo 78.9% (69.7–88.1). Se obtuvo una razón de verosimilitud positiva de 590 y razón de verosimilitud negativa de 0.266.

ConclusionesEl índice de riesgo de malignidad II tiene una adecuada eficiencia en la clasificación de mujeres posmenopáusicas con tumor anexial, tanto benigno como maligno, con una exactitud de la prueba del 81.8%.

Around 10% of women at some point in their lives will undergo a surgical assessment of an adnexal mass or for suspected ovarian cancer.1

Although the majority of adnexal tumours are benign, the principal objective of diagnostic evaluation is to exclude the possibility of a malignant process. The probability of finding malignancy in an adnexal tumour which does not look malignant is estimated at 4–6%.2,3

The risk of malignancy index was described by Jacobs et al. in 1990,4 and identifies patients at high risk of ovarian cancer.5 The risk of malignancy index II gives a rate based on: ultrasound features, menopausal status and preoperative Ca 125 levels, and uses up to 35U/ml as a normal value according to the equation below:

in which the ultrasound values (U), menopausal status (M) and the tumour marker (Ca 125) are multiplied; allocating a score to each.6–8A risk of malignancy index II value>200 indicates a high risk of malignancy. The risk of malignancy index II was more sensitive than the risk of malignancy index I with 78% sensitivity, 89–92% specificity.9

The objective of the study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the risk of malignancy index II in postmenopausal women with adnexal tumours in relation to histopathological results.

Material and methodsThe design of this study was observational, transversal, and analytical of the type of diagnostic test.

One hundred and thirty-eight postmenopausal women were included diagnosed with adnexal tumours by ultrasonography, and who had been operated either by laparoscopy or laparotomy in the Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad No. 23 of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social in the city of Monterrey, Nuevo Leon; in the period between 14 June 2011 and 17 May 2013. A data collection sheet was used for all patients to record their gynaecological variables (menarche, parity, years of menopause, reason for consultation, etc.), ultrasonographic variables, details of the surgical procedure, and results of histopathology.

The calculation of the risk of malignancy index II for each patient was made using the formula: IRM II=U×M×Ca 125. In this formula U represents the ultrasonographic index, where multilocular adnexal tumours, with the presence of solid areas, bilateral lesions, and the presence of ascitis or intraabdominal metastases are categorised with a score each, if they present such characteristics. Two or more characteristics will have a value of 4 and the absence of all findings suggestive of malignancy will be taken as 1. M represents menopausal status, one point for premenopausal women, and 4 for postmenopausal women. As the study population only included postmenopausal women, the standard value was 4 and the Ca 125 level was applied directly to the equation.

The patients were divided into two groups according to the histopathology results, 69 patients with benign tumours and 69 with malignant tumours. An association was made with contingency tables, taking into account the results of the risk of malignancy index II at≤200 (low risk) or>200 (high risk).

An analysis was made of the type of diagnostic test and the following obtained: sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio. Descriptive statistics of the groups were determined; for the categorical variables with measures of frequency, such as: mean or median and, dispersion measures such as: standard deviation and interquartile range. In the comparative analysis of the characteristics of the groups, for categorical variables Pearson's χ2 test was used for frequencies or where appropriate Fisher's exact test. The Student's t-test was used for the quantitative variables according to models of data distribution and equality of variances. The patients who did not meet the requirements were analysed with the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. The statistically significant value (alpha) was 0.05.

The information was collected on a database in Excel 2007 (Microsoft Office) and analysed using SPSS software for Mac version 20.

This study was authorised by Local Health Research and Ethics Committee No. 1905.

ResultsDuring a 2 year period of research in the Gynaecology – Oncology department of Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad No. 23, 138 postmenopausal patients with a diagnosis of adnexal tumour were studied.

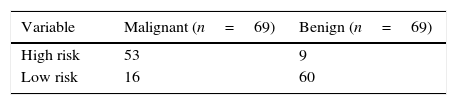

With respect to the analysis of the diagnostic test of risk of malignancy index II percentages and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were found for 81.8% accuracy (75.5–88.3), 76.8% sensitivity (66.9–86.7), 87% specificity (79.1–94.9), positive predictive value of 85.5% (76.7–94.3) and, negative predictive value of 78.9% (69.7–88.1). The positive likelihood ratio was 590 and the negative likelihood ratio was 0.266 (Table 1).

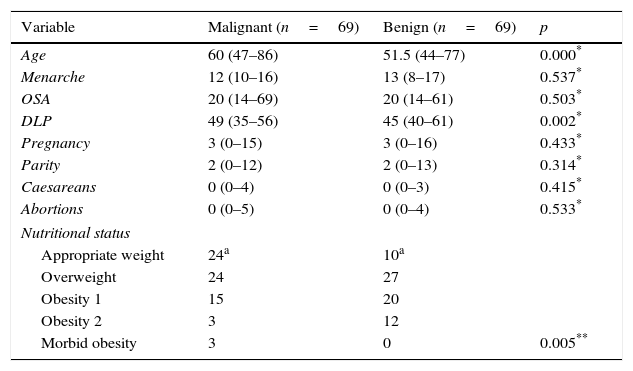

With regard to the demographic characteristics between groups, it was found that the median age of the patients with benign adnexal tumours was 51.5, and the median age of the patients with malignant adnexal tumours was 60, thus a statistically significant difference was established between the two groups. No statistically significant differences were found between the medians of both groups with regard to: menarche, onset of sexual activity or parity. The median age at the date of last menstruation in the patients with benign adnexal tumours was 45 and for the patients with malignant adnexal tumours it was 49; a statistically significant difference was found (p=0.002). With regard to nutritional status the χ2 test identified a statistically significant difference between the groups (p=0.005), an appropriate weight had a greater typified residue (−1.7) in the subanalysis (Table 2).

Comparison of demographic characteristics between the groups.

| Variable | Malignant (n=69) | Benign (n=69) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60 (47–86) | 51.5 (44–77) | 0.000* |

| Menarche | 12 (10–16) | 13 (8–17) | 0.537* |

| OSA | 20 (14–69) | 20 (14–61) | 0.503* |

| DLP | 49 (35–56) | 45 (40–61) | 0.002* |

| Pregnancy | 3 (0–15) | 3 (0–16) | 0.433* |

| Parity | 2 (0–12) | 2 (0–13) | 0.314* |

| Caesareans | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | 0.415* |

| Abortions | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–4) | 0.533* |

| Nutritional status | |||

| Appropriate weight | 24a | 10a | |

| Overweight | 24 | 27 | |

| Obesity 1 | 15 | 20 | |

| Obesity 2 | 3 | 12 | |

| Morbid obesity | 3 | 0 | 0.005** |

OSA: onset of sexual activity; DLP: date of last menstruation; p: level of statistical significance.

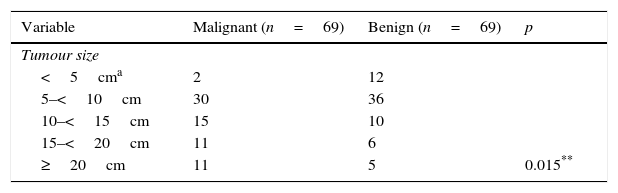

With respect to tumour size, in the category of tumours from 5cm to less than 10cm, a greater frequency was found in both the malignant and the benign tumour group, with 30 and 36 cases respectively. However, in the category of tumours of less than 5cm, two were found in the malignant group and 12 in the benign tumour group, the χ2 test showed a statistically significant difference (p=0.015) (Table 3).

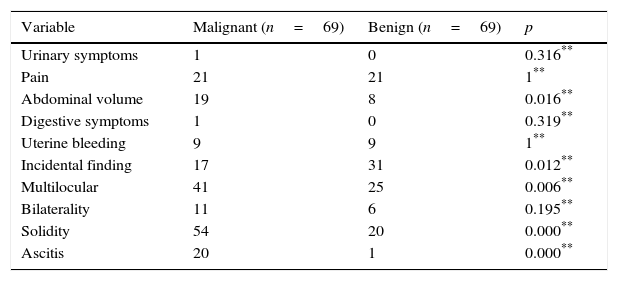

The most frequent clinical signs and symptoms prompting patients to seek consultation were abdominal pain, increased abdominal volume, an incidental finding, and abnormal uterine bleeding. However, the signs and symptoms which marked a statistically significant difference between the groups were increased abdominal volume (p=0.016), with 19 cases in the malignant tumour group and 8 in the benign tumour groups; as well as, being an incidental finding (p=0.012), with 17 cases in the malignant tumour group and 31 in the benign tumour group. The most frequent ultrasound features of the adnexal tumours in both groups were multilocular cyst with 41 cases in the malignant group and 25 in the benign (p=0.006), the presence of solid areas with 54 cases in the malignant tumours and 20 in the benign (p<0.05). The presence of ascitis was more frequent in the malignant tumour group, with 20 cases and only 1 in the benign tumour group; there was a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) (Table 4).

Analysis of the reasons for consultation and ultrasound features between the groups.

| Variable | Malignant (n=69) | Benign (n=69) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary symptoms | 1 | 0 | 0.316** |

| Pain | 21 | 21 | 1** |

| Abdominal volume | 19 | 8 | 0.016** |

| Digestive symptoms | 1 | 0 | 0.319** |

| Uterine bleeding | 9 | 9 | 1** |

| Incidental finding | 17 | 31 | 0.012** |

| Multilocular | 41 | 25 | 0.006** |

| Bilaterality | 11 | 6 | 0.195** |

| Solidity | 54 | 20 | 0.000** |

| Ascitis | 20 | 1 | 0.000** |

p: level of statistical significance.

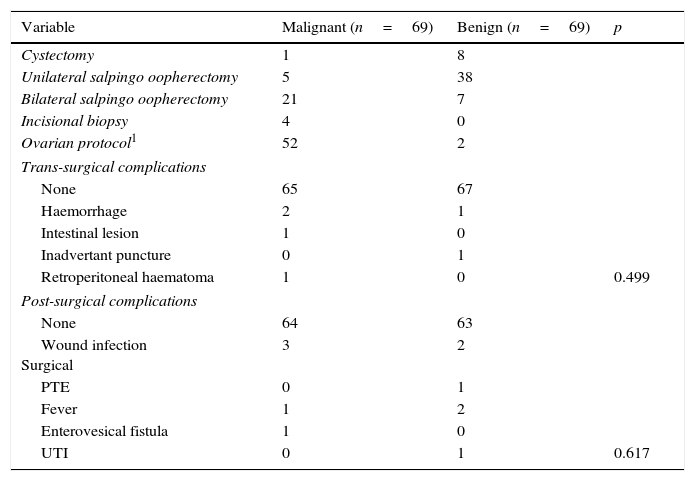

With regard to the type of resection it was found in the group of benign tumours that a unilateral salpingo oophorectomy was the most frequent procedure (38 cases) and in the malignant tumour group the ovarian protocol was used (52 cases). The surgical approach used in both groups was an exploratory laparotomy. In general there were few trans or post surgical complications, haemorrhage being the most frequent (>1000cm3) with 3 cases and surgical wound infection with 5 cases, respectively; no statistically significant value was found between the groups (Table 5).

Analysis with χ2 of surgical background and complications between groups.

| Variable | Malignant (n=69) | Benign (n=69) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cystectomy | 1 | 8 | |

| Unilateral salpingo oopherectomy | 5 | 38 | |

| Bilateral salpingo oopherectomy | 21 | 7 | |

| Incisional biopsy | 4 | 0 | |

| Ovarian protocol1 | 52 | 2 | |

| Trans-surgical complications | |||

| None | 65 | 67 | |

| Haemorrhage | 2 | 1 | |

| Intestinal lesion | 1 | 0 | |

| Inadvertant puncture | 0 | 1 | |

| Retroperitoneal haematoma | 1 | 0 | 0.499 |

| Post-surgical complications | |||

| None | 64 | 63 | |

| Wound infection Surgical | 3 | 2 | |

| PTE | 0 | 1 | |

| Fever | 1 | 2 | |

| Enterovesical fistula | 1 | 0 | |

| UTI | 0 | 1 | 0.617 |

UTI: urinary tract infection; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism.

p: level of the statistically significant value.

In the benign tumour group, the most frequent diagnosis was serous cystadenoma with 23 cases and in the malignant tumour group it was papillary serous cystadenoma with 26 cases.

DiscussionThe risk of malignancy index II is a simple algorithm to apply in clinical practice and uses laboratory and surgery tests which are affordable and easily reproducible. The risk of malignancy index was originally developed by Jacobs et al.4 in 1990. Subsequently, Tingulstad et al.6 developed the risk of malignancy index II in 1996. All the indexes presented a significantly better yield in detecting ovarian cancers with the use of a single parameter.9

It was demonstrated that using a cut-off point of 200 (irrespective of the score system) to evaluate a risk of malignancy index achieved a sensitivity of between 70% and 87%, and specificity of 89% and 97%. However, the risk of malignancy index uses ultrasound, which is operator-dependent, and this is subject to the equipment's image resolution capacity and possible variation between patient populations.10,11

Jacobs et al.4 reported sensitivity and specificity of 85.4% of 96.9%, respectively using the risk of malignancy index with a cut-off value of 200. Manjunath et al.12 found 73% sensitivity and 91% specificity, and attributed the low sensitivity to the high percentage of premenopausal women with ovarian cancer, compared with the initial studies of Jacobs et al.4,9,10

Several studies have demonstrated that the risk of malignancy index provides high levels of sensitivity, specificity and predictive values for evaluating adnexal tumours. However, a limitation with any study of a diagnostic test is that unlike sensitivity and specificity, the predictive values change according to the prevalence of the disease in a population. In our study the predictive values are subject to a 50% prevalence because of the way the sample was collected with two groups of an equal number of participants in relation to the diagnosis of adnexal tumour. However, the likelihood ratios which reflect the predictive yield of a test regardless of the prevalence were obtained and in the case of our study they showed an excellent positive likelihood ratio and a moderate negative likelihood ratio. The calculation of the risk of malignancy index was considered the method of choice as preoperative screening in patients with an adnexal tumour.10,13

In our study no relationship was observed between obesity and greater frequency of malignancy in contrast to other studies such as that of Dótlic et al.13 where they mention the correlation between the high values of the body mass index and the malignant histopathological results.

A variety of methods for the early detection of ovarian cancer have been investigated, an example is human epididymis protein 4, which is over-expressed in ovarian cancer, especially in serous epithelial tumours. This new marker has shown a similar sensitivity to Ca-125, but greater specificity to distinguish between patients with ovarian cancer and those with benign gynaecological disorders.8,14,15

It is recommended that this study should be extended to premenopausal women because up to 10% of adnexal tumours are malignant in this population. The results of the risk of malignancy index II can help to distinguish benign neoplasms which can be resected by the gynaecologist or otherwise detect malign neoplasms with a view to referring these patients to the oncological gynaecologist to be appropriately staged and to benefit from optimal cytoreduction in the event that they present disease evaluated according to metastatic stage. 8,16,17

It is important to mention that, although not part of the study objectives, all the surgical approaches were via laparotomy, which might imply a difference with the laparoscopic route in the analysis.

ConclusionsThe risk of malignancy index II performs well in the appropriate classification of postmenopausal women with adnexal tumours, both benign and malignant; the test has 81.8% accuracy and 95% CI of 75.5–88.3%.

The risk of malignancy index II is a reliable test for preoperative screening of postmenopausal women with adnexal tumours, with adequate values of positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, sensitivity and specificity, and therefore it is recommended that it should always be calculated.

It is recommended that menopausal patients, especially elderly patients, with a risk of malignancy index II greater than 200 should be referred to a third level healthcare centre where staging surgery for the risk of ovarian cancer can be performed if necessary.

It is considered appropriate that there should be a format for calculating the risk of malignancy index II and apply it systematically to every woman with an adnexal tumour, regardless of her age or menopausal status in order to screen for ovarian cancer.

It is advisable that this study should be extended to premenopausal women in order to detect adnexal disease early, and to make comparisons between the sensitivity and specificity values of the risk of malignancy index II in pre and post-menopausal women.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

To the Clinical Archive unit of the Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad No. 23 for their availability and helpful attention.

Please cite this article as: Treviño-Báez JD, Cantú-Cruz JA, Medina-Mercado J, Abundis A. Exactitud diagnóstica del índice de riesgo de malignidad II en mujeres posmenopáusicas con tumor anexial. Cir Cir. 2016;84:107–112.