Cystic echinococcosis is a zoonosis caused by larvae of the parasite Echinococcus that is endemic in many countries of the Mediterranean area. It can affect any organ, with the most common sites being liver (70%) and lung (20%). Splenic hydatid disease, despite being rare, is the third most common location. Other locations such as bone, skin, or kidney are exceptional.

ObjectiveTo present our experience in extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis.

Material and methodsPeriod: May 2007–December 2014. Health area: 251,000 inhabitants. During that period, a total of 136 patients with hydatid disease were evaluated in our Hepato-pancreatic-biliary Surgery Unit. Extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatid disease was found in 18 (13%) patients. A retrospective review was performed on all medical records, laboratory results, serology, diagnostic methods, and therapeutic measurements of all patients. An abdominal ultrasound and CT, as well as hydatid serology was also performed on all patients.

ResultsThe mean age of the patients was 44.5 years, with a range of 33–80 years. Half the patients (50%) had concomitant hepatic echinococcosis. Of the 18 patients with hydatid disease, 13 underwent surgery (radical surgery in 12 cases), and one underwent (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography)+puncture, aspiration, injection and re-aspiration. The remaining 4 did not have surgery due to patient refusal (3), or advanced cancer (1). No recurrences have been observed.

ConclusionThe best surgical treatment in these cases is closed total cystectomy to prevent recurrence, except in the spleen where splenectomy is preferred. Conservative techniques are indicated in cases of multiple hydatid disease and in patients with high surgical risk.

La hidatidosis es una zoonosis producida por las larvas del parásito Echinococcus, endémica en muchos países del Mediterráneo. Puede afectar a cualquier órgano. Las localizaciones más frecuentes son: el hígado (70%) y el pulmón (20%). La hidatidosis esplénica es la tercera localización más habitual. Otras localizaciones como la ósea, cutánea o renal son excepcionales.

ObjetivoPresentar nuestra experiencia en hidatidosis extrahepática y extrapulmonar.

Material y métodosEl periodo de este estudio fue de mayo de 2007 a diciembre de 2014. En una población de 251,000 habitantes. En dicho periodo en la Unidad de Cirugía Hepatobiliopancreática fue evaluado un total de 136 pacientes con hidatidosis; 18 pacientes presentaron hidatidosis extrahepática y extrapulmonar (13%). Se revisaron retrospectivamente las historias clínicas, estudios de laboratorio (serologías) y gabinete, métodos diagnósticos y medidas terapéuticas, realizadas en todos los pacientes. Además, se realizó una ecografía y tomografía axial computada abdominal, y serología hidatídica.

ResultadosLa edad media de los pacientes era de 44.5 años, rango: 33–80 años. La mitad de los pacientes (50%) presentaron hidatidosis hepática concomitante. De los 18 pacientes, 13 fueron intervenidos quirúrgicamente (12 con cirugía radical) y a uno se le realizó punción, aspiración, instilación y reaspiración+colangiopancreatografía retrógrada endoscópica; los 4 restantes no fueron operados por negativa del paciente (3) o neoplasia avanzada (1). No se observó ninguna recidiva.

ConclusionesEl tratamiento quirúrgico de elección es la quistectomía total cerrada, para evitar la recidiva, excepto en el bazo, que es la esplenectomía. Las técnicas conservadoras están indicadas en casos de hidatidosis múltiple y en pacientes con alto riesgo quirúrgico.

Hydatosis is a zoonosis caused by the larvae of the Echinococcus parasite. There are various subtypes; Echinococcus granulosus is the most common.1,2 This disease is endemic in certain geographical areas (Mediterranean countries, Australia and South America). The number of diagnosed cases in Spain had reduced in recent years, but the growing emigration from other endemic areas and deficient health control in certain communities has increased its current incidence.3 It can affect any organ, although the most frequent locations are the liver (70% of cysts), followed by the lung (20%). Splenic hydatidosis is the third most common location (0.5%–8% of patients with hydatidosis according to the different series consulted), and it is rare for it to present in isolation, without liver or pulmonary involvement.1,4 Other sites, such as bone, skin or kidney are exceptional.

Hydatid cysts are classified based on Gharbi's classification, and the different types of presentation are divided into 3 groups: active, transitional and inactive.

Cystic echinococcosis 1, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) presents wall characteristics with or without small mobile echoes (hydatid sand), and are fertile cysts. Cystic echinococcosis 2 (WHO) is Garbhi type iii and considered fertile (active).

ObjectiveThe study aim is to present our experience in 18 patients with extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis, and the corresponding therapeutic options.

Material and methodsA descriptive, cross-sectional study, performed from May 2007 to December 2014 in the hepatobiliopancreatic surgery unit in our hospital, which attends 251,000 inhabitants. Over this period we assessed a total of 136 patients with hydatidosis. The selection criterion was the location of the hyatidosis, extrahepatic and extrapulmonary, regardless of the other parameters. A total of 18 patients presented extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis (13% of the total). The clinical histories, laboratory reports, serologies, diagnostic methods and therapeutic measures of all the patients were reviewed retrospectively. In addition, ultrasound, abdominal computed axial tomography and hydatid serology were undertaken. Surgery was indicated for active or complicated cysts, except in the case of severe or negative morbidity of the patient on intervention. Follow-up was undertaken by imaging tests and periodic serology.

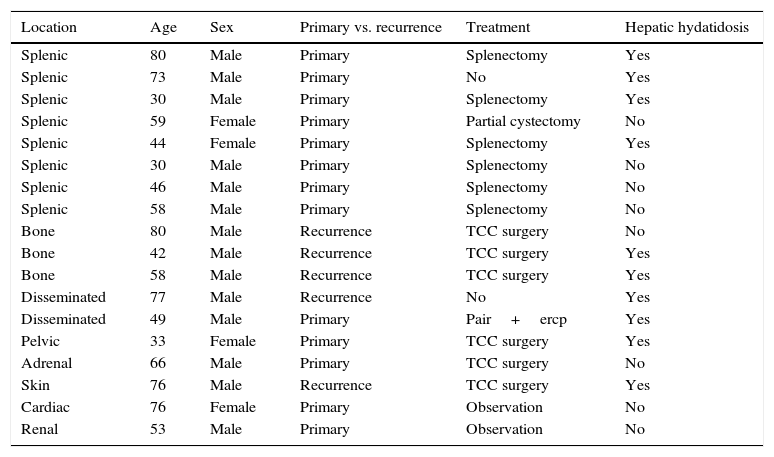

ResultsIn our series of 18 patients, 14 were male and 4 female. The mean age of the patients was 44.5 years, with an age range between 33 and 80 years. The location of the hydatidosis was: splenic in 8 of the cases, bone (3), disseminated peritoneal (2), cardiac (1), renal (1), adrenal (1), subcutaneous (1) and pelvic (1); 9 patients (50%) synchronously presented hepatic hydatidosis.

Of the 18 patients included in the study (Table 1), 13 were operated and one underwent puncture-aspiration-injection-reaspiration and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Twelve of the 13 patients operated underwent radical surgery of the extrahepatic lesions (6 splenectomies and 6 total cystectomies) and only one was treated by conservative surgery (partial cystectomy). The 4 that were neither operated nor treated were splenic hydatidosis with stage vi unresectable gallbladder cancer (1), disseminated (1), cardiac (1) and renal hydatidosis (1). The decision not to intervene surgically was taken for the following reasons: 73-year-old male diagnosed with single splenic hydatidosis of 5cm, concomitant with an stage vi unresectable gallbladder cancer; asymptomatic disseminated hydatidosis in and 83-year-old male, who refused treatment of any type; the renal and the cardiac hydatidosis were not operated since they were inactive, asymptomatic cysts, and therefore were controlled radiologically and followed up in the outpatient department.

Characteristics of our series.

| Location | Age | Sex | Primary vs. recurrence | Treatment | Hepatic hydatidosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Splenic | 80 | Male | Primary | Splenectomy | Yes |

| Splenic | 73 | Male | Primary | No | Yes |

| Splenic | 30 | Male | Primary | Splenectomy | Yes |

| Splenic | 59 | Female | Primary | Partial cystectomy | No |

| Splenic | 44 | Female | Primary | Splenectomy | Yes |

| Splenic | 30 | Male | Primary | Splenectomy | No |

| Splenic | 46 | Male | Primary | Splenectomy | No |

| Splenic | 58 | Male | Primary | Splenectomy | No |

| Bone | 80 | Male | Recurrence | TCC surgery | No |

| Bone | 42 | Male | Recurrence | TCC surgery | Yes |

| Bone | 58 | Male | Recurrence | TCC surgery | Yes |

| Disseminated | 77 | Male | Recurrence | No | Yes |

| Disseminated | 49 | Male | Primary | Pair+ercp | Yes |

| Pelvic | 33 | Female | Primary | TCC surgery | Yes |

| Adrenal | 66 | Male | Primary | TCC surgery | No |

| Skin | 76 | Male | Recurrence | TCC surgery | Yes |

| Cardiac | 76 | Female | Primary | Observation | No |

| Renal | 53 | Male | Primary | Observation | No |

TCC: total closed cystectomy.

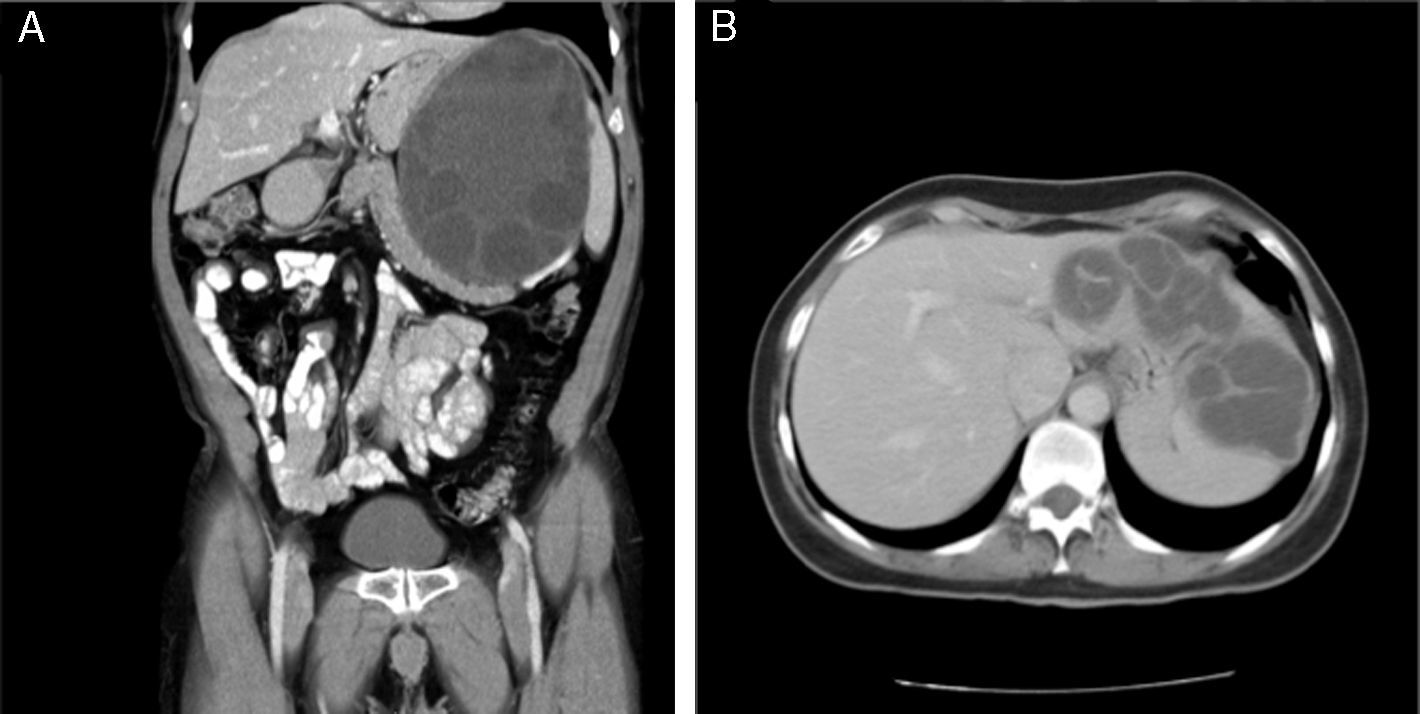

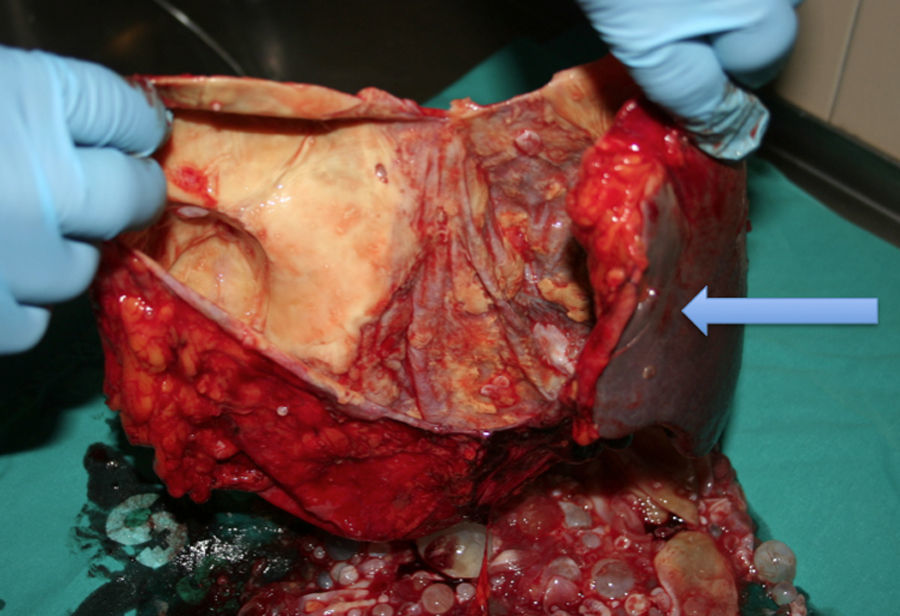

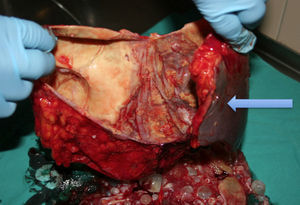

Splenic hydatidosis. Of the 8 cases of splenic hydatidosis, 7 patients were operated (87.5%); 4 patients presented splenic hydatidosis alone, the other 4 presented splenic and hepatic hydatidosis concomitantly; 6 were treated by total splenectomy and one patient underwent partial cystectomy for a cyst of 16cm, which encompassed the diaphragm, stomach and retroperitoneum. In addition, as associated procedures, one patient underwent a subsegmentectomy of liver segment III, with a cyst of 18cm that was intimately joined to the liver, and left lateral sectionectomy in one patient with hepatosplenic hydatidosis (Fig. 1A and B).

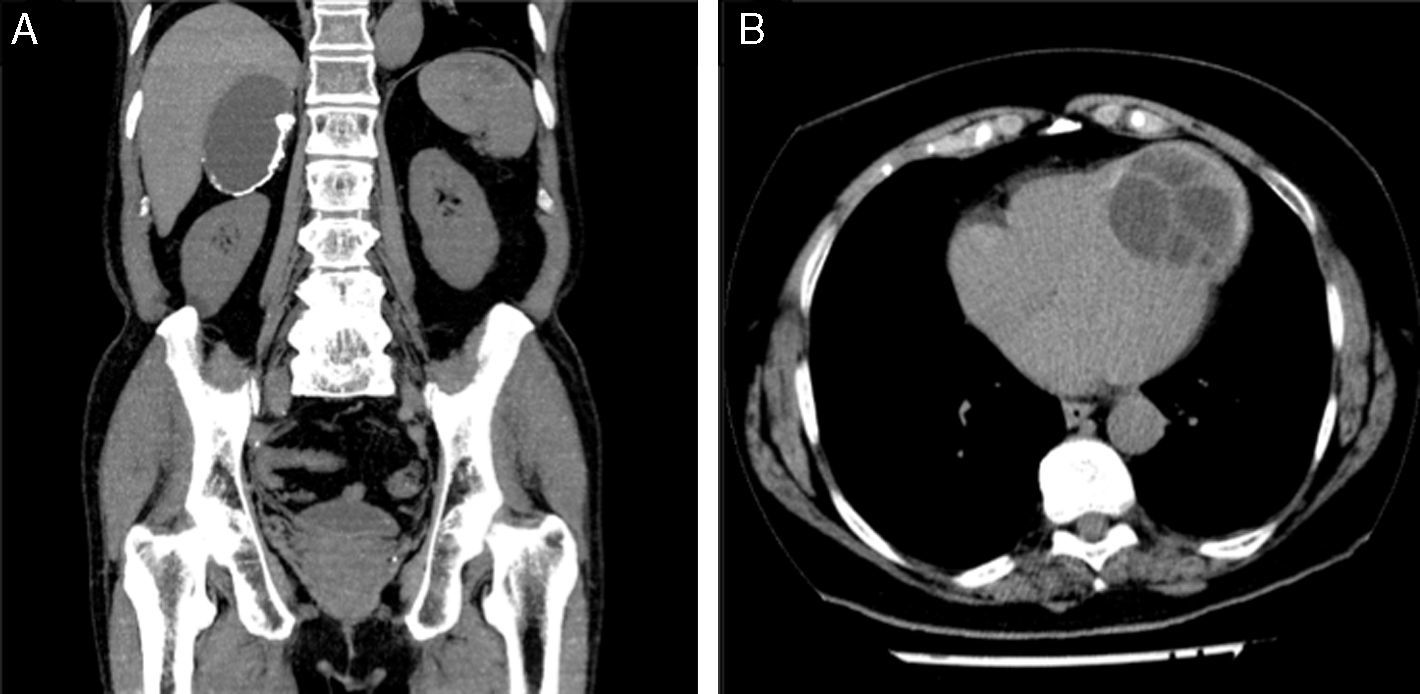

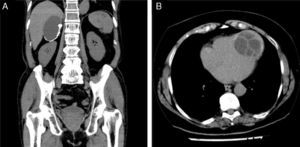

Bone hydatidoses. Bone hydatidoses were found located in the right iliac crest (2 patients) and the right femur. Two of the 3 cases presented concomitant liver hydatidosis; 2 patients had undergone conservative surgery previously (Fig. 2A), and presented recurrence, therefore they underwent total closed cystectomy of the cysts in the bone and liver. The third case of primary bone hydatidosis without liver hydatidosis underwent total closed cystectomy.

Surgical specimen of Fig. 1A. Arrow: spleen.

Disseminated peritoneal hydatidosis. The 2 cases of disseminated peritoneal hydatidosis were 2 males, aged 83 and 46 years. The former had been operated 30 years previously with a total closed cystectomy of the hepatic cysts, and partial cystectomies of multiple liver and peritoneal cysts. He currently has disseminated hydatidosis with multiple cysts throughout the abdomen and is being treated with albendazole, with radiological control and follow-up as an outpatient, since he refused reoperation because he was asymptomatic. The second patient had been operated on 5 occasions over the past 14 years, the first operation was due to anaphylactic shock secondary to intra-abdominal rupture of the cyst, after abdominal trauma. He underwent puncture-aspiration-injection and reaspiration of 2 symptomatic cysts, with abdominal and lumbar pain, and subsequently underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and placement of a plastic prosthesis for cysto-biliary communication, since the patient refused other surgical options.

Other locationsPelvic hydatidosis. Total closed cystectomy of the cyst was performed and an almost total cystectomy of the hepatic hydatid cyst.

Adrenal hydatidosis (Fig. 3A). No concomitant liver hydatidosis presented, therefore a total closed cystectomy of the adrenal cyst was performed.

Skin hydatidosis. Total cystectomy and removal of subcutaneous and muscle tissue. The patient had been operated previously for hepatic hydatidosis.

Renal and cardiac hydatidosis (Fig. 3B). The patients are under follow-up with periodic radiological controls, since they were asymptomatic and refused surgery.

Mean follow-up was 32 months (range: 18–60), in the operated patients (7 splenic, 3 bone, one pelvic, one adrenal and one skin hydatidosis). No recurrence was seen in any of the cases. The patients with disseminated hydatidosis are currently asymptomatic, under follow-up as outpatients. The patients with renal and cardiac hydatidosis who were not operated continue to be asymptomatic and their lesions are stable according to the radiological controls. The patient with gallbladder cancer died due to progression of the disease.

DiscussionHydatidosis can affect any anatomic site, due to its haematogenous dissemination. Extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis is a very rare entity that comprises 10% of hydatosis in general.5 It can appear as a primary, exclusively in an extrahepatic organ, concomitant with hepatic and pulmonary hydatidosis, or due to peritoneal spread secondary to rupture of an intra-abdominal hepatic hydatid cyst. Classically the latter is considered the most common form. Of the 18 patients included in this series of extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis, 10 presented associated liver hydatidosis, but only 2 presented a known rupture of a hepatic hydatid cyst.

The age of presentation and distribution by gender of extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis differ widely depending on the series. The clinical manifestations are non-specific, although it is most common for the cysts to be asymptomatic and their diagnosis incidental. When they are symptomatic, abdominal pain or pain in the affected region is the most frequent symptom.1,6

A diagnosis of extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis is made based on a combination with a positive serology result for hydatidosis, if a hepatic or pulmonary hydatid cyst is shown on imaging tests. The diagnostic technique of choice is helicoidal computed axial tomography, although the findings are not specific.2,6,7 Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful for bone or cardiac hydatidosis.

The spleen, despite being a rare location for hydatidosis (0.5%–8%), is the most common site after the liver and the lung.1,4,8 Splenic hydatidosis occurs primarily when the larva crosses the hepatic or pulmonary filters, reaches the spleen and causes the cyst. Secondarily it is caused by the rupture of an intra-abdominal cyst, usually hepatic, or due to invasion of a nearby cyst.

At the level of the bone, the most affected bone is the spine (up to 35% of cases), followed by the pelvis and femur. With bone involvement the pericyst does not form, because the cysts present a much finer wall than in other sites. Due to the absence of pericyst and the hardness of bone, bone cysts tend to take on an elongated rather than rounded morphology, since they extend through the areas of least resistance.5

Renal hydatidosis occurs in 3% of cases of hydatidosis.5,9–12 The most common symptom is the sensation of an abdominal mass, pain and dysuria, which generally occurs in large, solitary cysts, which can be up to 10cm. They can also be asymptomatic. In most cases they are located at the level of the renal cortex.10

Cerebral hydatidosis occurs in 1% of cases9,10 and is usually diagnosed in infancy. Peritoneal hydatidosis is generally secondary to rupture of a hydatid cyst in a different location; hepatic in the majority of cases, although cases of primary peritoneal hydatidosis are described in the literature.13

The surgical indications and therapeutic options for extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis have not been well defined. Routinely the same indications are used as for hepatic hydatidosis and patients with active, complicated or symptomatic cysts are operated.3 Although these indications can be used for splenic, pelvic, renal and adrenal cysts, in other locations particular characteristics should be considered. Treatment of bone cysts can cause significant functional loss and therefore should be very carefully evaluated.

Patients with disseminated hydatidosis will have undergone many previous laparotomies. For this reason, the large majority refuse further surgery, except those with symptoms. Therefore the morbidity associated with these operations should be evaluated and they should only be indicated in the event of complications such as intestinal obstruction or severe pain. The indication for surgery of cardiac hydatidosis should be very selective.

The therapeutic options are: (a) periodic observation in asymptomatic cases or inactive cysts and if the patient refuses surgery; (b) treatment with albendazole, either to attempt to stabilise the disease or as a measure prior to surgery, the great disadvantage is that it has been demonstrated that in cases of hepatic or pulmonary hydatidosis, albendazole reduces the size and number of protoscolices, but in extrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis this effect has not been demonstrated and there is no scientific evidence to recommend it; (c) percutaneous drainage with puncture-aspiration-injection-reaspiration combined with albendazole can be useful compared to surgical cystectomy in terms of hospital stay and rate of complications, in patients at high surgical risk, patients with disseminated hydatidosis,14 multi-operated patients or those who decline surgery15–17 and (d) finally, surgery.

Extrahepatic and extrapulmonary surgical removal of hydatid cysts obtains the best outcomes in recurrence percentage. Therefore it should be used in cases of splenic, adrenal, pelvic, cutaneous and renal hydatidosis. The technique of choice is total cystectomy except with the spleen, which is then splenectomy. In technically complex cases where the risk posed by surgery is excessive, conservative techniques should be used. There is minimal recurrence after complete removal.

ConclusionExtrahepatic and extrapulmonary hydatidosis can be diagnosed in any organ. Because its incidence is so low, there are no treatment guidelines and the concepts used for hepatic hydatidosis are employed. Treatment should adapt to the characteristics of the cyst, the organ affected and the preferences of the patient. Radical surgery achieves excellent outcomes with a low recurrence rate.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Adel F, Ramia JM, Gijón L, de la Plaza-Llamas R, Arteaga-Peralta V, Ramiro-Perez C. Hidatidosis extrahepática y extrapulmonar. Cir Cir. 2017;85:121–126.