Gallstone ileus is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction (1–4%). It results from the migration of a gallstone through a bilio-enteric fistula. Treatment begins with fluid therapy, followed by enterolithotomy, fistula closure, and cholecystectomy.

ObjectivesTo determine the clinical presentation in patients with gallstone ileus and subsequent medical-surgical management outcomes.

Material and methodsA retrospective, observational, descriptive and transversal study was conducted on patients diagnosed with intestinal obstruction secondary to a gallstone ileus from May 2013 to October 2014. The following variables were recorded: age, sex, comorbidities, mean time of onset of symptoms, length of preoperative and postoperative stay, imaging studies, biochemical tests, type of surgical management, stone location and size, complications, mortality, and postoperative follow-up.

ResultsThe study included 10 patients (male:female ratio, 1:4), with a mean age of 61.9 years. The mean time of onset symptoms 15.4 days, and preoperative stay was 2 days. On admission, 80% of patients had leukocytosis and neutrophilia, and 70% with renal failure. The most common surgical management was enterolithotomy with primary closure (50%), finding 80% of the stones in the terminal ileum. Recurrence was found in 2 cases. Mean postoperative hospital stay was 6.3 days. Mortality was 20%.

ConclusionsGallstone ileus most commonly presented in women in the seventh decade of life, with intermittent bowel obstruction. On hospital admission, they presented with systemic inflammatory response, electrolyte imbalance and abnormal liver function tests. Initial treatment must include fluid-electrolyte replacement, and tomography scans must be made in all cases. In our experience, the best procedure is enterolithotomy and primary closure, which presented lower morbidity and mortality.

El íleo biliar es una causa infrecuente de oclusión intestinal (1-4%), producida al migrar un lito por una fístula bilioentérica. El tratamiento consiste en reanimación hídrica, enterolitotomía, cierre de fístula y colecistectomía.

ObjetivosDeterminar las condiciones de presentación clínica de pacientes con íleo biliar y su evolución posterior al manejo médico-quirúrgico.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo, observacional, descriptivo y transversal de pacientes ingresados con el diagnóstico de oclusión intestinal, debida a íleo biliar. De mayo del 2013 a octubre del 2014, registramos las siguientes variables: edad, sexo, comorbilidades, duración del cuadro clínico, estancia preoperatoria y postoperatoria, imagenología, resultados de laboratorios, manejo quirúrgico, ubicación y tamaño de litos, complicaciones, recidiva, seguimiento postoperatorio y mortalidad.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 10 pacientes (relación hombre: mujer 1:4), edad media 61.9 años, media de tiempo de cuadro clínico 15.4 días, estancia preoperatoria 2 días; el 80% presentó leucocitosis y neutrofilia, falla renal el 70%. La cirugía más realizada fue enterolitotomía con cierre primario (50%). El 80% de los litos se localizaron en íleon terminal. Hubo 2 recidivas. Media de estancia postoperatoria de 6.3 días y mortalidad del 20%.

ConclusionesEl íleo biliar se presentó en mujeres de la séptima década de la vida, con cuadro de oclusión intermitente de larga evolución. Al ingreso presentaban datos de respuesta inflamatoria sistémica, desequilibrio hidroelectrolítico y alteraciones en pruebas funcionales hepáticas. Se debe realizar una adecuada reanimación hidroelectrolítica y tomografía en todos los casos. El mejor procedimiento, en nuestra experiencia, es enterolitotomía y cierre primario; este último es el que presenta menor morbimortalidad.

Gallstone ileus, according to Beuran et al.1 was described by Bartholin in 1654 in an autopsy.1 It is a mechanical intestinal obstruction due to the impaction of one or more gallstones in the gastro-intestinal tract, secondary to a biliodigestive fistula.2,3 The first case of duodenal obstruction was described by Bonnet in 1841, but Bouveret established a preoperative diagnosis of a similar situation as late as 1893. The first reported case of an obstruction in the colon was in 1932, by Tunner.1–3

Since 1990, gallstone ileus has been described as a rare complication of cholelithiasis that occurs in 1–4%, and represents up to 25% intestinal obstructions in people over the age of 65.4 Approximately 50% of patients with gallstone ileus have a history of cholelithiasis, but only 0.3–1.5% of patients with cholelithiasis go on to present gallstone illeus.5,6

It can present from the age of 13 to 97 years, more common in females (male:female ratio from 2.3:1 to 16:1).7

The apparently most common mechanism of gallstone ileus is migration of a stone from the gallbladder to the duodenum via a cholecystoduodenal fistula (68–95%).1 However, the possibility is also mentioned of fistulas that involve the stomach and colon.2 The mean measurement of these stones is 2.5cm.1

The migrating stone commonly lodges in the terminal ileum or the ileocaecal valve, segments of the intestine where there is reduced movement and calibre.1

There are 3 forms of clinical presentation: acute, the classical presentation of gallstone ileus; subacute, presenting as partial intestinal occlusion and chronic, known as Karewsky's syndrome, characterised by repeated episodes of pain that abate as the stone passes through the intestine.1

The most common biochemical alterations are: hypopotassaemia (60%), hyponatraemia (40%) and metabolic alkalosis (40%).5 Treatment is based on hydroelectrolytic resuscitation of the patient and surgical management of the disease itself.1 Traditionally management was by exploratory laparotomy plus enterolithotomy. According to Ravikumar and Williams,2 the first description was made in 1929 by Holz of the procedure termed “one-stage” to prevent recurrence of gallstone ileus.

Morbidity and mortality is high, up to 21%, associated with advanced age and the presence of chronic degenerative disease.8

ObjectiveTo determine the general conditions and clinical presentation on admission of patients with gallstone ileus, and its outcome, based on the medical and surgical treatment given.

Material and methodsA retrospective, observational, descriptive and transversal study was undertaken from 1 May 2013 to 30 October 2014, in the general emergency surgery department of the Hospital General de México Dr. Eduardo Liceaga, in Mexico City.

All patients operated with a diagnosis of gallstone ileus were included in the study, taking the following variables into account: age, gender, comorbidities, duration of clinical symptoms, preoperative hospital stay time, imaging studies, biochemical tests on admission, type of surgical management, site and size of stones, post-operative hospital stay, complications, recurrence, post-operative follow-up, symptoms on discharge and morality. Patients from whom all these variables could not be gathered were excluded.

The data were compared with the total number of cholecystectomies performed in the same period of time, and the total number of patients operated by laparotomy for intestinal occlusion. For each of the variables analysed the central tendency measures and dispersion were established; this analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2010.

ResultsWe obtained a total of 10 patients in the time period; no patient was excluded from the study. Of the total, 8 were female (80%) and 2 male (20%). The mean age of presentation was 61.9 years, with standard deviation (SD) ±15.8, 70% of the patients were aged over 55 years.

In total, in the same study period 484 laparotomies due to intestinal occlusion were recorded, of which gallstone ileus comprised 2.06% of cases. In addition, 402 surgical procedures were performed due to gallstone disease, of which 2.48% were due to gallstone ileus.

Of the 10 patients, only 2 presented associated comorbidities. One patient presented chronic alcohol abuse and paroxystic tachycardia and another presented vegetative neuropathy as a complication of Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The time from the onset of symptoms until arriving at the Emergency department ranged between 4 and 30 days, with a mean of 15.4 and SD ±12.86. It is important to mention that none of the patients presented in this series had a history of biliary colic or episodes of acute cholecystitits. The symptoms presented by all of the patients corresponded with a clinical picture of intestinal occlusion.

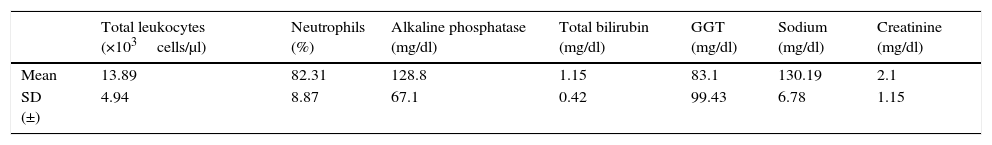

Various laboratory tests were carried out on admission and 80% of the patients were found to have leukocytosis and neutrophilia, with a mean of 13.89×103cells/μl (SD ±4.95) and 82.31% (SD ±8.87), respectively. Seventy percent of the patients presented signs of acute renal failure, with a mean creatinine level of 2.1mg/dl (SD ±1.15) and urea 82.94mg/dl (SD ±51.31). Hydroelectrolytic alterations were common: in our series, 80% presented hyponatraemia, 40% hypopotassaemia and 50% hypochloraemia. With regard to liver function tests, only 4 of the 10 patients presented slight elevations of total bilirubin, with a mean of 1.15mg/dl (SD ±0.42), 50% presented elevated alkaline phosphatase and 50%, elevated gamma glutamyl transpeptidase levels (Table 1).

Result of laboratory tests on admission.

| Total leukocytes (×103cells/μl) | Neutrophils (%) | Alkaline phosphatase (mg/dl) | Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | GGT (mg/dl) | Sodium (mg/dl) | Creatinine (mg/dl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 13.89 | 82.31 | 128.8 | 1.15 | 83.1 | 130.19 | 2.1 |

| SD (±) | 4.94 | 8.87 | 67.1 | 0.42 | 99.43 | 6.78 | 1.15 |

SD: standard deviation; GGT: gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; mg/dl: milligrams/decilitres.

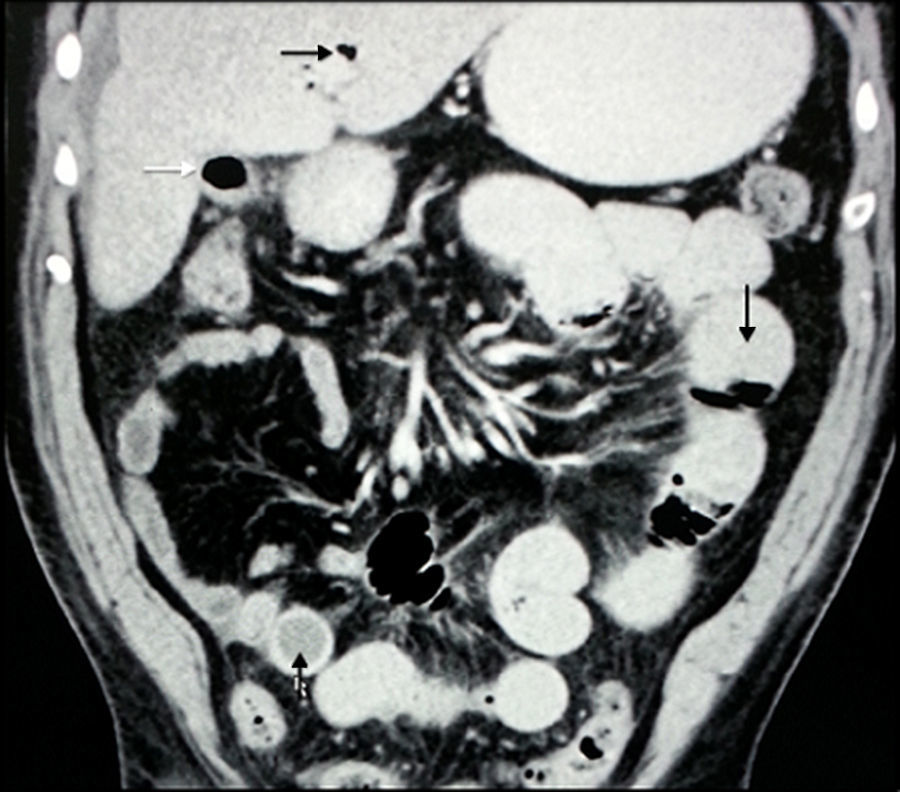

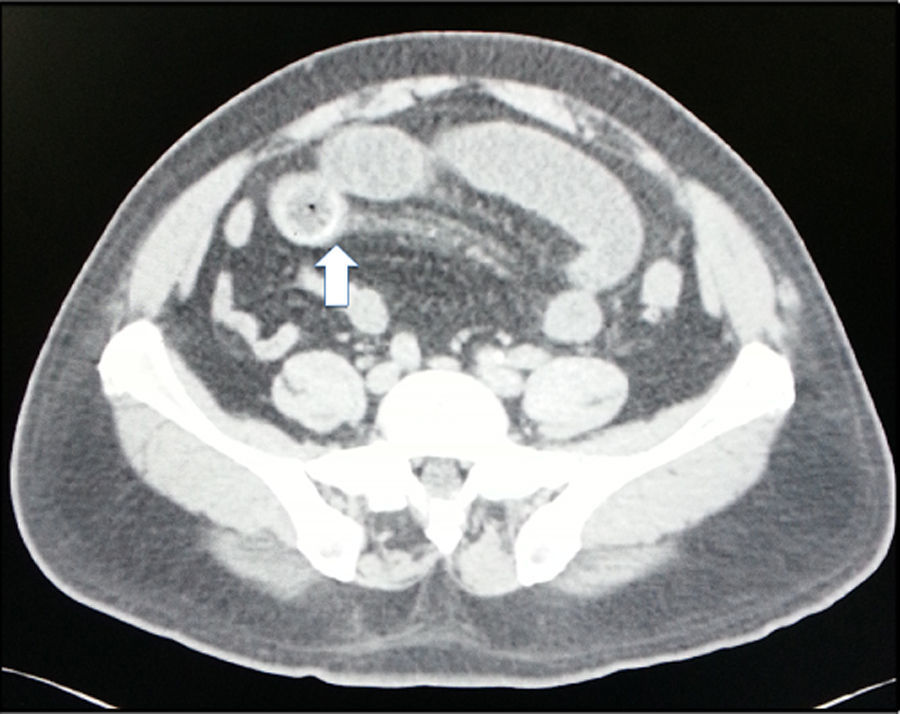

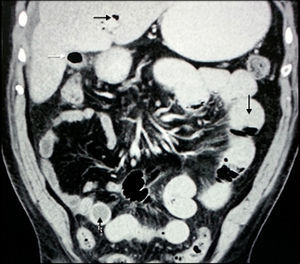

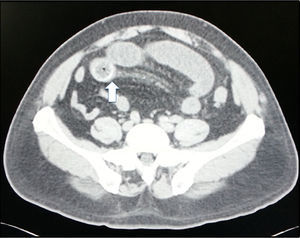

The mean preoperative stay in the emergency department was 2 days (SD ±1.84). Within this time, all the patients were X-rayed in 2 positions; Rigler's triad was not found in any of the cases. Ninety-percent of the patients underwent abdominal CT scan: Rigler triad was found in 100% (Figs. 1 and 2).

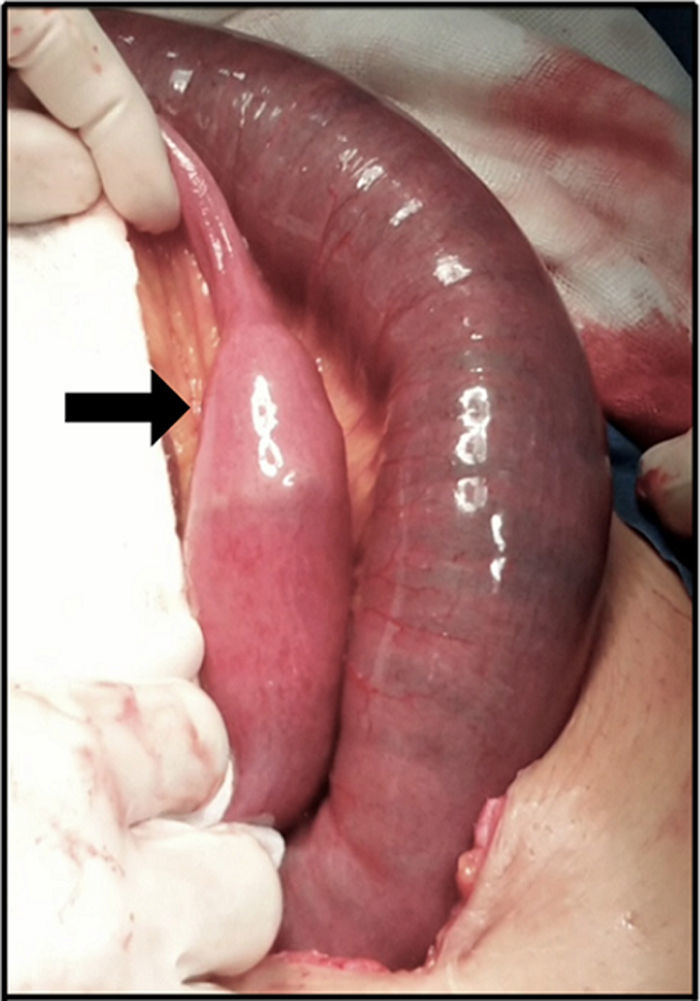

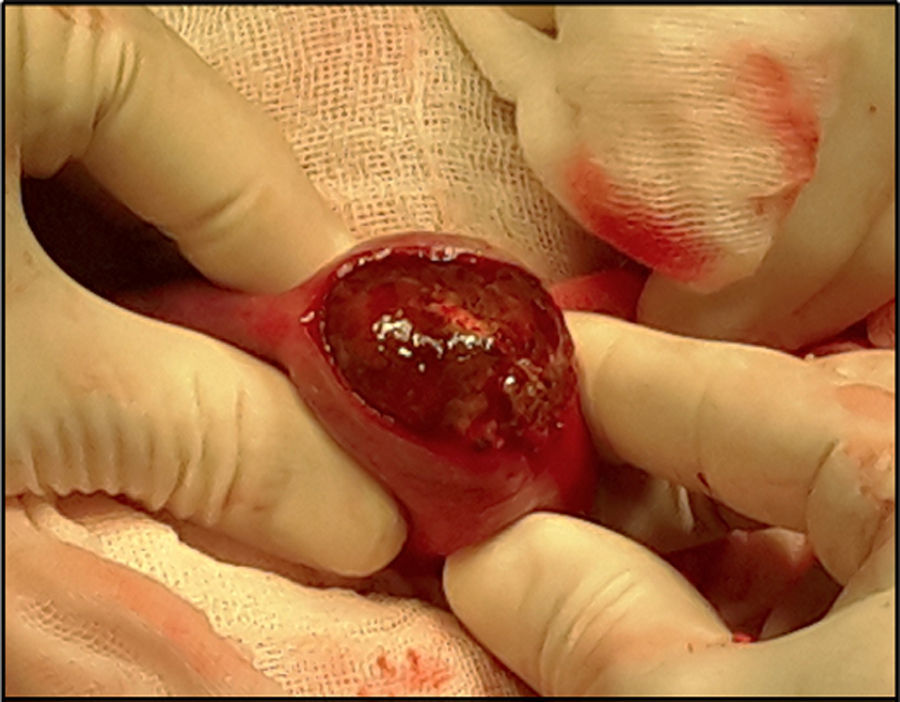

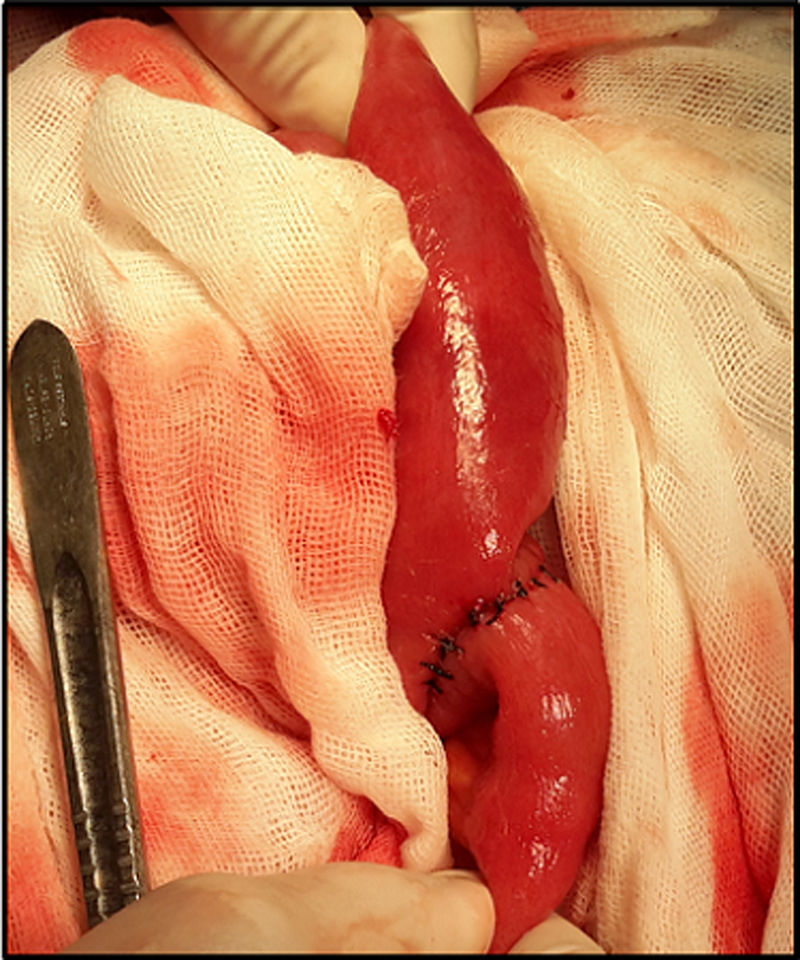

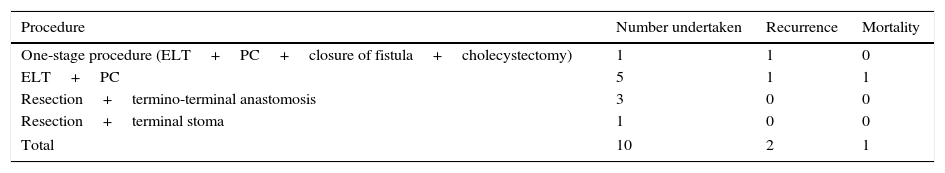

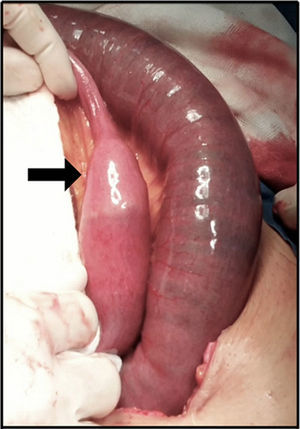

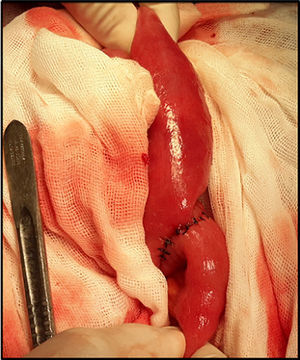

Ninety percent of the patients underwent laparotomy with a prior diagnosis of gallstone ileus (Fig. 3). The main procedure performed was enterolithotomy with primary closure (Figs. 4 and 5). Other management is summarised in Table 2.

Surgical management carried out in the Emergency Department.

| Procedure | Number undertaken | Recurrence | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-stage procedure (ELT+PC+closure of fistula+cholecystectomy) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| ELT+PC | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Resection+termino-terminal anastomosis | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Resection+terminal stoma | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 10 | 2 | 1 |

ELT+PC: enterolithotomy+primary closure.

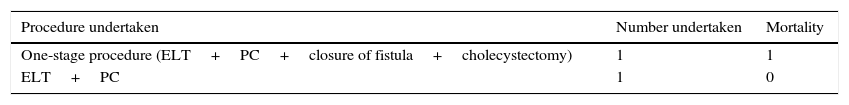

Two patients out of the ten included in the study presented recurrence. The first patient presented recurrence 15 days after the first procedure (enterolithotomy with primary closure) and the second patient 30 days after the first surgical procedure (one-stage procedure). Table 3 summarises the procedures carried out and the mortality after the second procedure.

The location of the stones was in the ileum in 80% and in the jejunum in 20% of the cases. The mean size of the stones was 4.5cm at the widest point (Fig. 6).

The mean postoperative stay was 6.3 days (SD ±4.19). Three of the patients presented sepsis, 2 due to enterorrhaphy dehiscence and the other due to pneumonia secondary to bronchoaspiration. Out of the total of our patients, 2 died during their hospital stay, one due to abdominal sepsis after recurrence and the other due to aspiration pneumonia.

We followed-up the remaining 8 patients postoperatively; this was impossible to complete in 2 cases. The remaining patients were followed up over a mean 6.1 months, during which time one patient was admitted 3 months postoperatively with pyelonephritis, she developed urosepsis and died. The remainder are under follow-up.

Postoperative symptoms presented as mild abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium in one patient, one patient had constipation and the other pruritis and granuloma in the surgical wound.

DiscussionGallstone ileus is an uncommon cause of intestinal occlusion and a rare complication of vesicular lithiasis. Most cases present in patients after the sixth decade of life. It usually predominates in females. In our series 70% of cases were aged over 55 years, with a male to female ratio of 1:4, which coincides with the literature.

Pathophysiologically it is accepted that large and solitary stones erode the gallbladder wall and that of the intestine, causing chronic inflammation, which reduces arterial flow, venous and lymphatic drainage, and encourages necrosis and the formation of biliodigestive fistula.9 The migrating stone commonly becomes lodged in the terminal ileum or the ileocaecal valve, segments of the intestine with reduced mobility and calibre.1 Gallstones increase in size as they advance through the digestive tract, due to the addition of intestinal content, until they reach the point of impaction. This happens when the stone measures more than 2.5cm.10 In our series, all the stones measured were larger than 2.5cm.

According to reports, this disease represents a proportion of 0.9% of admissions to emergency departments for surgical reasons, with a mean hospital stay of 14 days (postoperative stay 9.5 days).11 In our series the mean postoperative stay was less, at 6.3 days, and overall 8.3 days.

Only in 50–60% of cases is a diagnosis established prior to surgical intervention.6,7 In our hospital, the study protocol for patients with intestinal occlusion involves oral and intravenous contrast abdominal CT scan (provided this is possible, depending on renal function). Therefore a preoperative diagnosis was achieved in 90% of cases. In our experience, tomographic imaging of these patients enables better planning of the surgical procedure.

The characteristic diagnostic image is Rigler's triad (only present in 15% of cases on abdominal X-ray).12 This comprises: dilation of proximal bowel loops with air-fluid levels (typically in the upper left quadrant), pneumobilia and an image of calcified stone (in the lower right quadrant).13 A further two signs are added, change of position of the stone and evidence of air-fluid levels in the gallbladder. The presence of 2 or more of these signs is considered pathognomonic of gallstone ileus.3 The low sensitivity reported on plain abdominal X-rays coincides with our results, where none of the X-rays showed Rigler's triad. Ultrasound of the liver and the bile duct can detect pneumobilia and ectopic stones. Its use along with abdominal X-ray increases sensitivity to 74%.1

Rigler's triad can be found in up to 80% of cases through the timely use of abdominal computed tomography (CT),12 and shows the presence of pneumobilia, ectopic stones in the intestine, chronic cholecystitis and cholecystoenteric fistula.1 Some case series report improved accuracy and faster diagnosis using abdominal CT (93% sensitivity).2 Nine of our patients underwent abdominal CT: we found Rigler's triad in 100% of cases.

Appropriate hydroelectrolytic resuscitation is the cornerstone of medical treatment, since, as was seen in our results, the majority of patients presented hydroelectrolytic imbalance and acute renal failure at time of diagnosis. Martínez Ramos et al.11 reported that in 12.5% of their patients (n=40), the stone was expelled rectally, after initial therapy based on decompression by nasogastric tube, hydroelectrolytic management and supportive measures.

The surgical management of gallstone ileus is controversial, the options include: enterotomy or intestinal resection, with removal of the stone. In both cases the procedure can be completed with biliary fistula closure and cholecystectomy.4 Elderly patients with multiple comorbidities (ASA III) present a real challenge, since they present with a considerable increase in leaks, intestinal and biliary, when the one-stage procedure is performed.10 In the latter case, special care needs to be taken in intraoperative decision-making. In patients with a longer life expectancy, with no comorbidities and greater technical skills, it is possible to resolve the disorder in one stage.11

The mortality reported by Martínez Ramos et al.11 was 11%, which reached 25% in patients with comorbidities. These authors found no difference in the surgical complications of patients treated by enterolithotomy and those treated with enterolithotomy plus closure of fistula. A Croatian series of 30 patients reported a postoperative morbidity of 61.1%, with one-stage treatment, vs 27.3% when an enterolithotomy alone was undertaken, with a mortality of 10.5 vs 9% respectively.2,14 Reisner and Cohen published the largest case series, reporting a mortality of 16.9% and 11.7% for one-stage repair procedures and enterolithotomy, respectively.15

Some case reports mention that gallstone ileus can present up to 8 months after cholecystectomy.16 Detailed revision of the entire small bowel tract during surgery for gallstone ileus is essential in order to avoid recurrence.17 If a faceted gallstone is found during enterolithotomy, it is imperative to carry out a thorough check of the intestine for an additional stone.7 In our series we report 2 recurrences, with a maximum presentation time of 30 days. It is important to mention that, although the procedure is performed in one stage, recurrence can occur, as in one of our cases.

One-stage treatment can be performed when it has been assessed that cholecystectomy is technically simple, always using cholangiography to evaluate the integrity of the bile duct and transverse closure of the duodenum on one or 2 planes.18 The biliodigestive fistula closes spontaneously in more than 50% of cases, after management with enterolithotomy.4

Laparoscopic treatment is possible, paying particular attention when inserting the first trocar, since the intestinal loops are dilated and injury can occur. We recommend the open technique for placing the first trocar. The intestinal loops that are not dilated can be exteriorised, through a back-up port, and enterolithotomy performed through a transverse primary closure.19

Alternative therapeutic methods include laser colonic lithotripsy, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy+argon, and endoscopic hydroelectric laser lithotripsy. These methods are only possible when the stone is in the colon, proximal duodenum or stomach.1

Historically, surgical wound infection and closure or anastomosis dehiscence are the most common complications, at 25–50% of cases. Other complications are acute renal failure, urinary infection, anastomotic leaks, abdominal abscess, and septic shock. Retrospective cohorts and literature reviews report malignancy in the bile duct in up to 2–6% of cases.4

ConclusionsIn our series we found that patients were typically female, in the seventh decade of life, with no significant comorbidities with symptoms typical of intestinal occlusion of 2 weeks’ duration on average. No case presented episodes of gallbladder colic or acute cholecystitis. On admission they presented leukocytosis and deviation of the distribution curve to the left, prerenal signs of renal failure, hydroelectrolytic imbalance, and in 50% of the cases, elevated alkaline phosphatase and elevated gamma glutamyl transpeptidase levels, with no hyperbilirubinaema.

In our experience, strict hydroelectrolyte resuscitation is recommended on admission, along with abdominal CT scan for the patients where this picture is suspected. We consider that the surgical procedure that should be undertaken in the first instance is enterolithotomy with primary enterorrhaphy and, in cases with signs of intestinal ischaemia or where satisfactory enterotomy is not possible, resection of the segment and entero-enteroanastomosis.

Principal morbidity in the immediate postoperative period was hydroelectrolytic imbalance and sepsis, due to the baseline diagnosis or bronchoaspiration.

Decision-making should be based on the patient's general condition. Because this disease predominantly presents in older adults, caution should be exercised when performing the one-stage procedure. In our experience, there was a lower rate of morbidity and mortality after enterolithotomy and primary closure alone.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Pérez EA, Álvarez-Álvarez S, Madrigal-Téllez MA, Gutiérrez-Uvalle GE, Ramírez-Velásquez JE, Hurtado-López LM. Íleo biliar, experiencia en el Hospital General de México Dr. Eduardo Liceaga. Cir Cir. 2017;85:114–120.