Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a cause of intestinal obstruction of unknown etiology. Also known as abdominal cocoon syndrome, it is characterized by a fibrocollagenous membrane that either completely or partially encompasses the small bowel.1 This causes patients to repeatedly seek medical care for symptoms of intestinal obstruction. Both symptoms as well as radiological images are non-specific, and diagnosis therefore requires elevated suspicion.2,3

We present the case report of a 54-year-old male patient with no prior history of interest, except for bilateral endoscopic hernioplasty that was completely extraperitoneal and recent elective surgery for cholelithiasis. It was during this latter surgery that sclerosing peritonitis was incidentally diagnosed when a whitish membrane that affected the small bowel and descending colon was found intraoperatively, blocking the supramesocolic compartment as well.

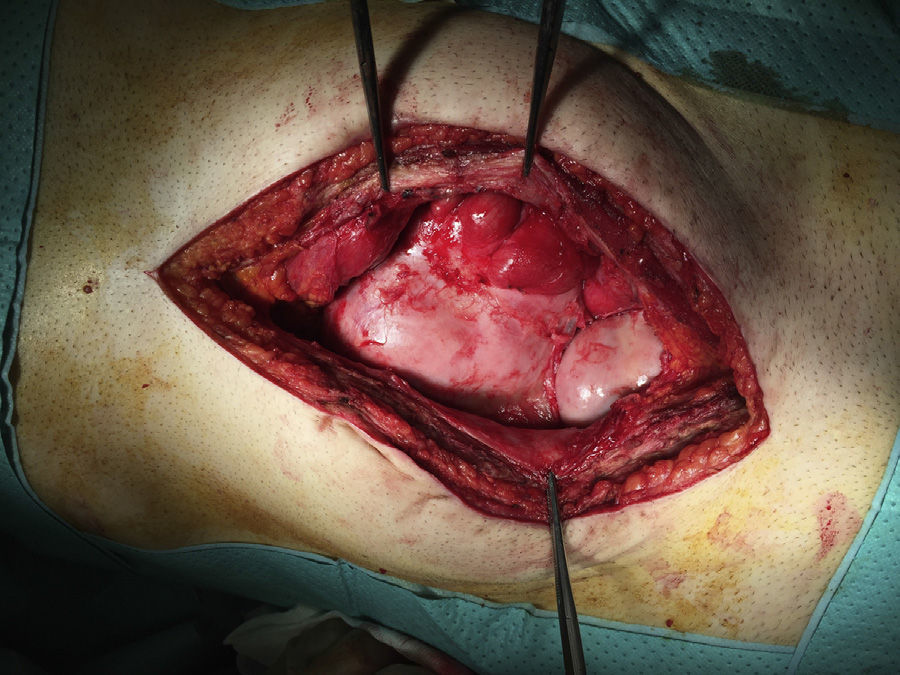

Afterwards, the patient came to the Emergency Department on repeated occasions due to colicky abdominal pain and subacute intestinal obstruction, so he was hospitalized once again. Physical examination detected abdominal distension associated with a palpable mass in the mesogastrium. A CT scan demonstrated medialized small intestinal loops, some with wall thickening, that were adhered amongst themselves and to the anterior abdominal wall; there was also free interloop fluid, which was probably related to adhesion-related syndrome. We decided to schedule surgery, and found a membrane covering the jejunum and a large part of the ileum (Fig. 1). We performed almost complete exeresis of the membrane, that could be separated from the serosa of the intestine. The integrity of the bowel loops was confirmed up to the ileocecal valve; no perforations were observed, and resection was not required. The patient's condition progressed favorably, and he was discharged 6 days after surgery with complete resolution of the symptoms.

Abdominal cocoon syndrome is a very uncommon disease of unknown etiology that is classified as either idiopathic or secondary. This latter form is more common, and there have been descriptions of cases of secondary SEP associated with peritoneal dialysis, tuberculosis, treatment with beta-blockers, familial Mediterranean fever, etc. The idiopathic form of SEP is relatively more frequent in tropical countries, and in a greater proportion in young women. Some hypotheses have been proposed as causes of this idiopathic form, such as retrograde menstruation associated with a viral infection or through the Fallopian tubes, although neither has been demonstrated.3 In some patients, a relationship has been described between SEP and other embryologic alterations like omental hypoplasia and sclerotic retracted intestinal mesentery. This syndrome is characterized by a fibrotic membrane that completely or partially encapsulates the small bowel and may envelop other organs, such as the large bowel, liver and stomach.4 These patients present recurring episodes of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, malnutrition, recurring crises of total or partial intestinal obstruction, while in some cases an intraabdominal mass is frequently palpated during physical examination. Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion, and most cases described in the literature are diagnosed during surgery.5

The preoperative diagnosis is made in patients with repeated symptoms of intestinal obstruction and suspicious CT scans6 that show images of a small bowel loop conglomeration in the center of the abdomen that is encapsulated in a membrane (Fig. 2). Interloop ascites is also frequently observed.

Treatment of idiopathic SEP in symptomatic patients involves surgery.7 The most widely used surgical technique is total or partial excision of the membrane and adhesiolysis of the affected small bowel loops. This reduces the need for intestinal resection, which should only be used in cases where it is considered unavoidable.1,2 Adequate preoperative nutritional support in these patients has been observed to reduce postoperative complications and increase postoperative satisfaction.8

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare having received no funding to complete this article, nor were there any conflicts of interests.

Please cite this article as: Illán Riquelme A, Camacho Lozano J, Abdalahi H, Calado Leal C, Huertas Riquelme J. Síndrome de Cocoon: una rara causa de oclusión intestinal. Cir Esp. 2016;94:417–419.