Traditionally, 2 surgical techniques for proctectomy in ulcerative colitis have been used: total mesorectal excision (TME), and close rectal dissection (CRD). Recently, our research group has proposed the standardization of the Near-TME technique, which unites the advantages of both methods. It decreases the risk of pelvic autonomic nerve injury and reduces the volume of mesorectal remnant. When performing the Near-TME, the anatomical landmarks differ between men and women, especially in the anterolateral hemicircumference. The objective of this paper is to standardize the Near-TME technique in women (Female Near-TME) using characteristic surgical-anatomic landmarks of the female pelvis based on illustrations and a real case treated laparoscopically.

This technique should be carried out by surgeons with experience in inflammatory bowel disease surgery and extensive knowledge of surgical anatomy.

Dos técnicas quirúrgicas de proctectomía en colitis ulcerosa han sido empleadas tradicionalmente; la escisión total de mesorrecto (TME) y la disección perirrectal (CRD). Recientemente, el presente grupo de trabajo ha propuesto la estandarización de la técncia Near-TME, la cual reúne las ventajas de éstas dos. Disminuye el riesgo de lesión nerviosa autónoma pélvica y disminuye el volumen de remanente mesorrectal. Las referencias anatómicas a la hora de realizar la Near-TME varían entre el varón y la mujer, sobre todo en la hemicircunferencia anterolateral. El objetivo del presente trabajo es estandarizar la técnica de Near-TME en mujeres (FEMALE NEAR-TME) a partir de landmarks anatomoquirúrgicos característicos de la pelvis femenina a partir de ilustraciones y de un caso real intervenido de forma laparoscópica.

Esta técnica debe ser llevada a cabo por cirujanos con experiencia en cirugía de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal y con amplios conocimientos anatomoquirúrgicos.

Within 10 years of their initial diagnosis, 16% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) require surgery.1 Two surgical techniques are used for proctectomy in UC: total mesorectal excision (TME) and close rectal dissection (CRD).2,3 However, the main guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease recommend a dissection that combines both techniques, without providing a description of the technique or assigning it a proper name.2

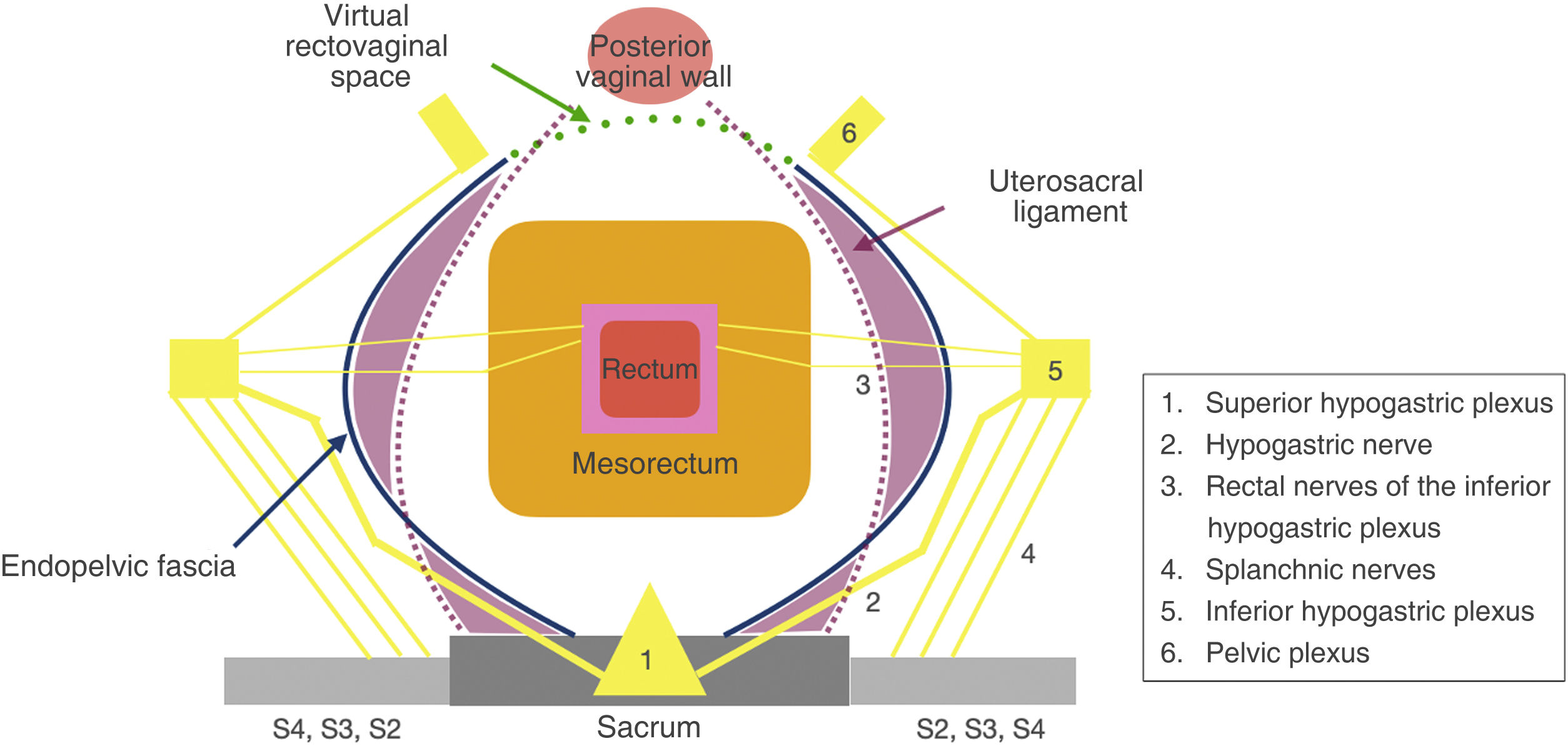

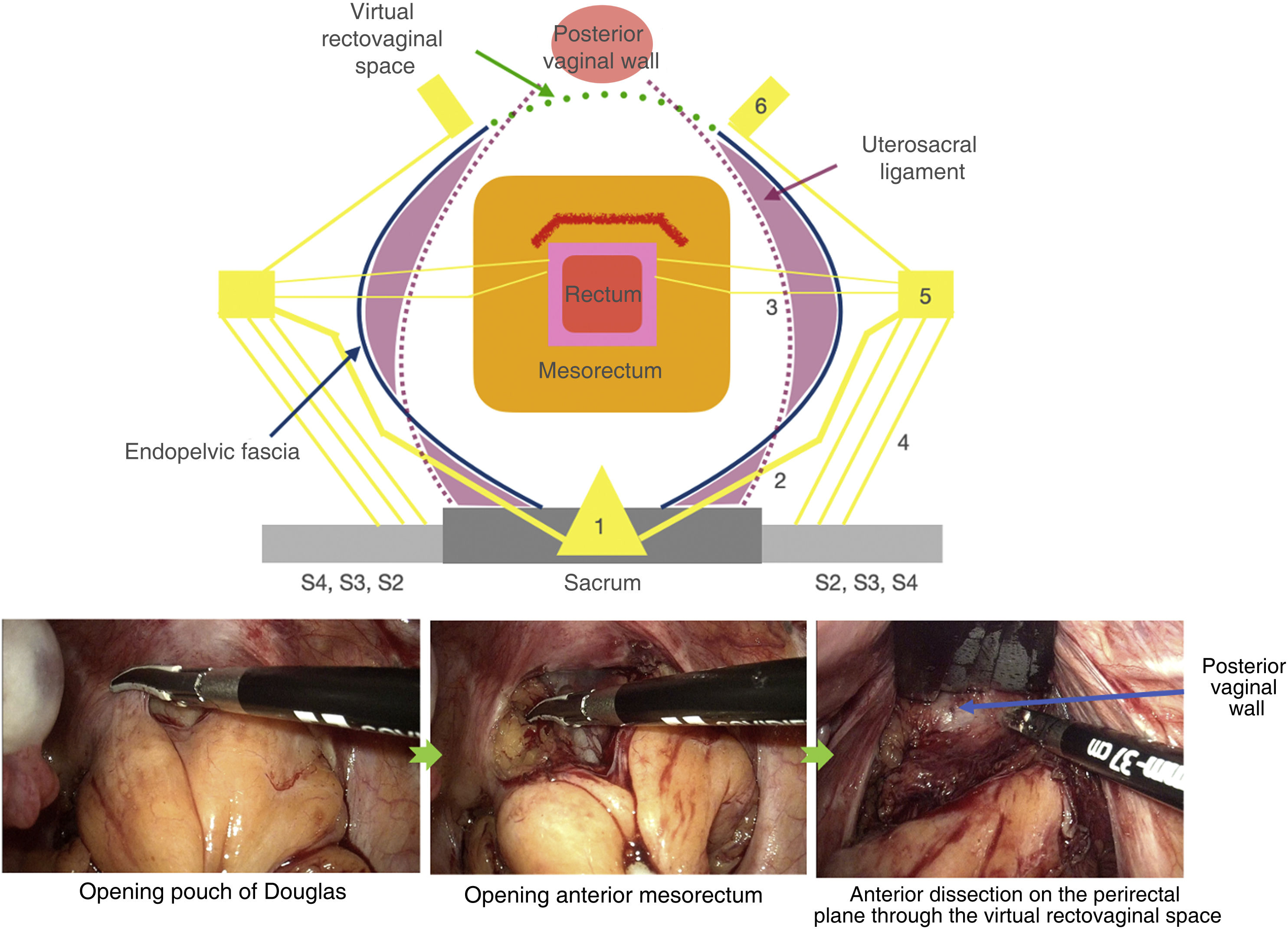

In a recent publication, our working group has proposed the standardization of this technique, calling it Near-TME.2 Said article demonstrates the main anatomical landmarks to conduct the technique and reduce the chances of injury to the pelvic autonomic nerves and nerve plexi (Fig. 1).2,4 However, the description focuses on proctectomy in males.

The objective of this paper is to standardize the Near-TME technique for females (Female Near-TME) based on illustrations, as well as the case of a patient who was treated laparoscopically. In addition, we will address the advantages and disadvantages of this technique compared to TME or CRD in terms of female genitourinary and sexual function.

Surgical techniqueThe patient is a 46-year-old female with UC who had undergone total colectomy with end ileostomy 10 years earlier due to poor response to medical treatment. At that time, proctectomy was not performed due to severe malnutrition and longstanding corticosteroid treatment. The patient presented mucus and rectal bleeding. Rectoscopy showed proctitis, and biopsies confirmed ulcerative colitis with moderate activity.

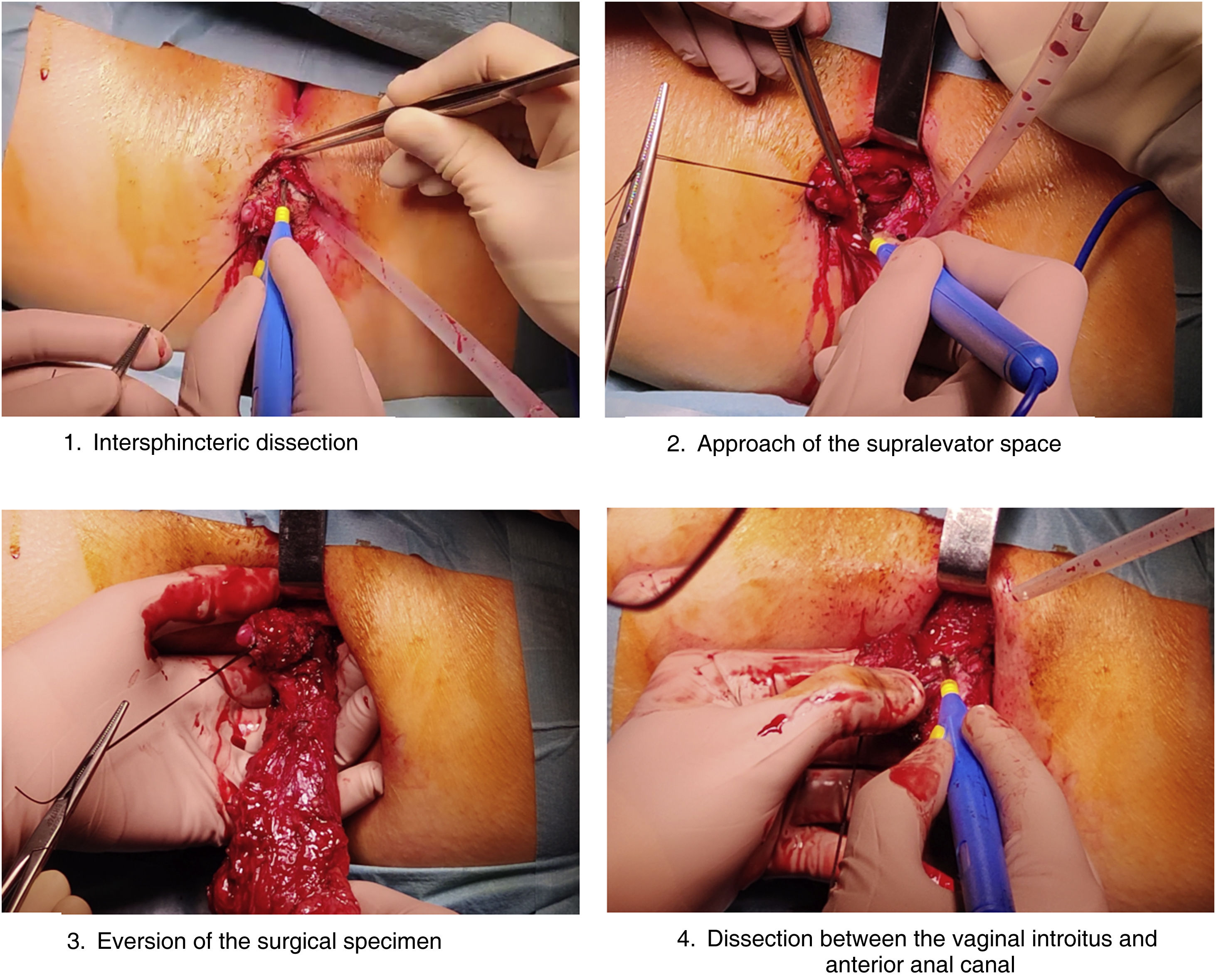

Due to the worsening of the symptoms despite several changes in medical treatment, we decided to operate. The patient agreed to intersphincteric proctectomy, which was performed using the Near-TME technique (Video 1). Given the patient’s history of several perianal fistulae, we reached the decision with the patient to rule out the creation of an ileoanal reservoir.

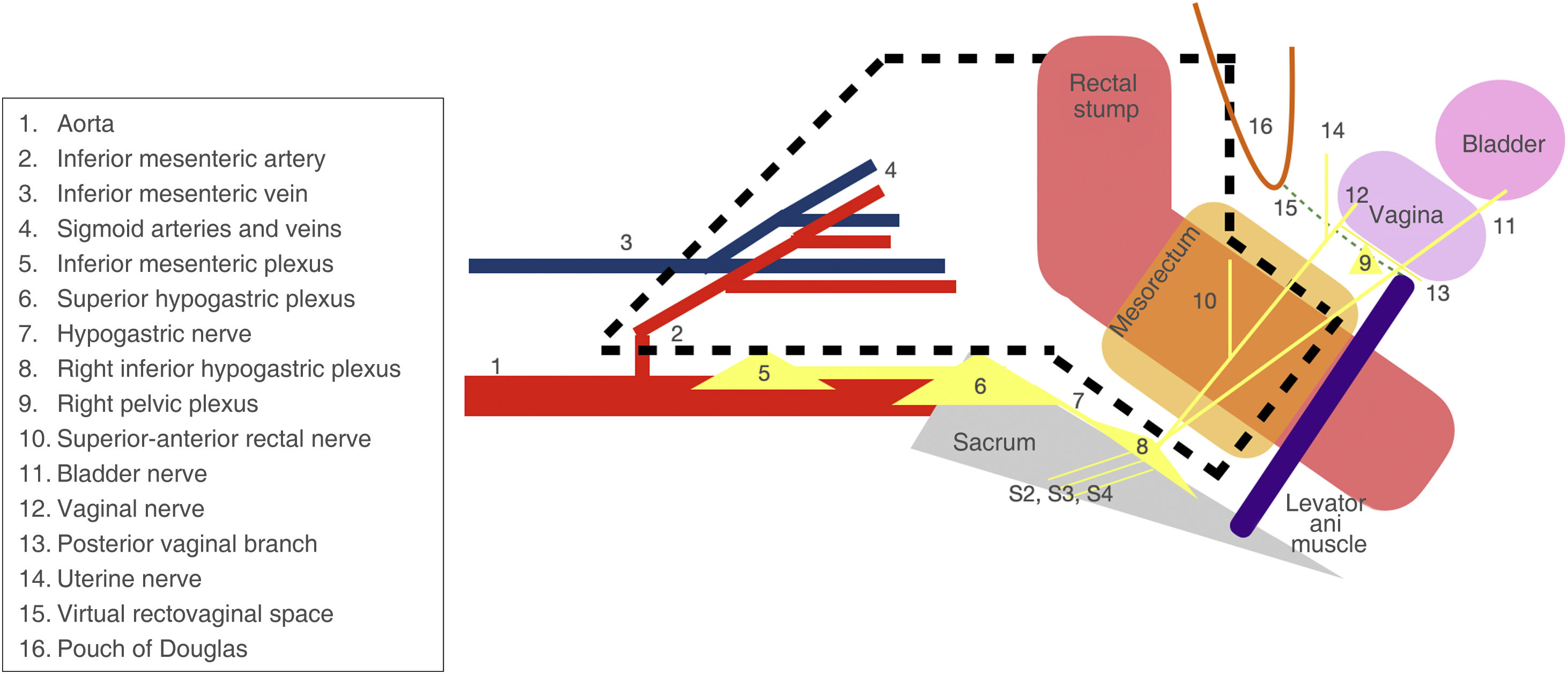

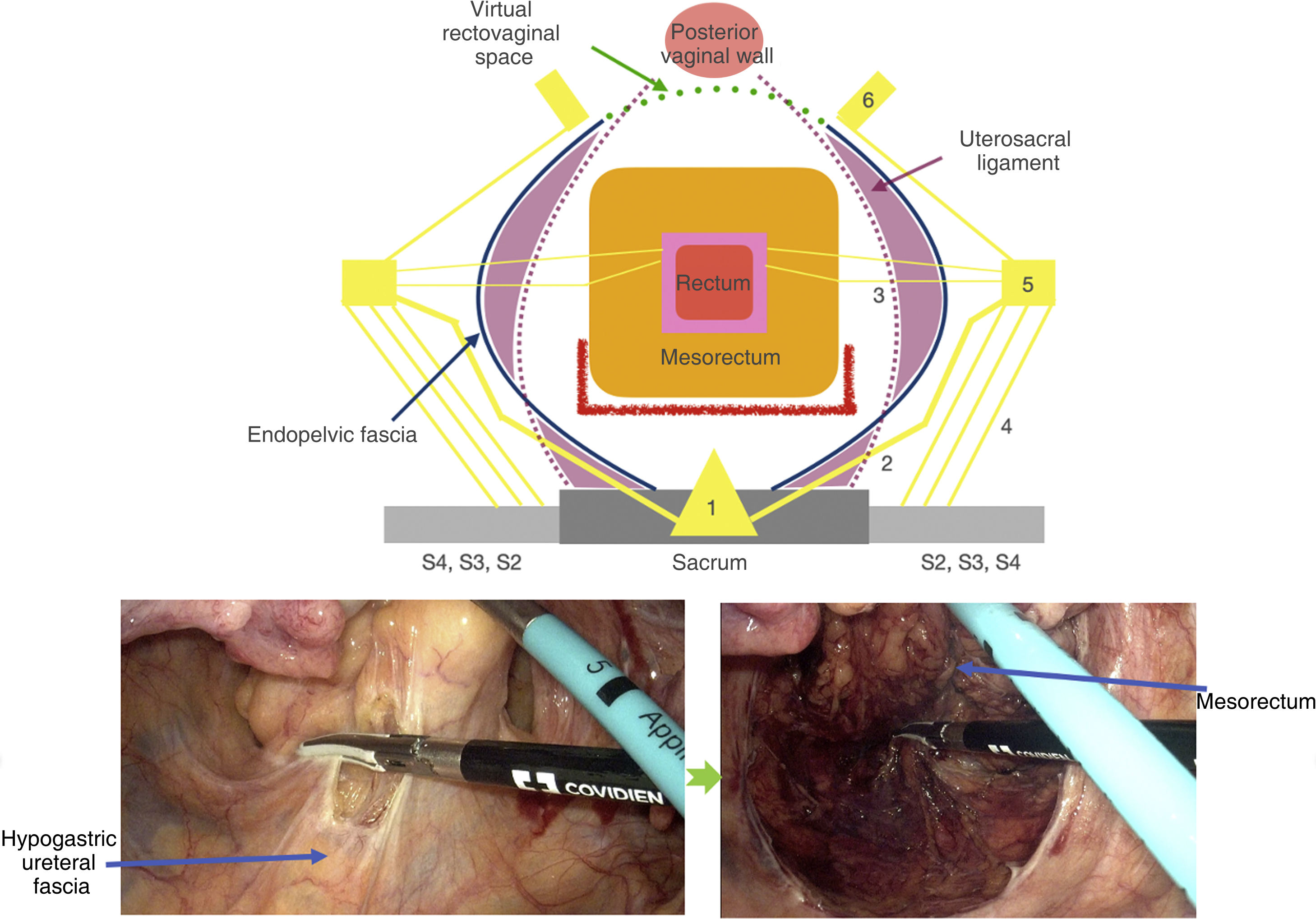

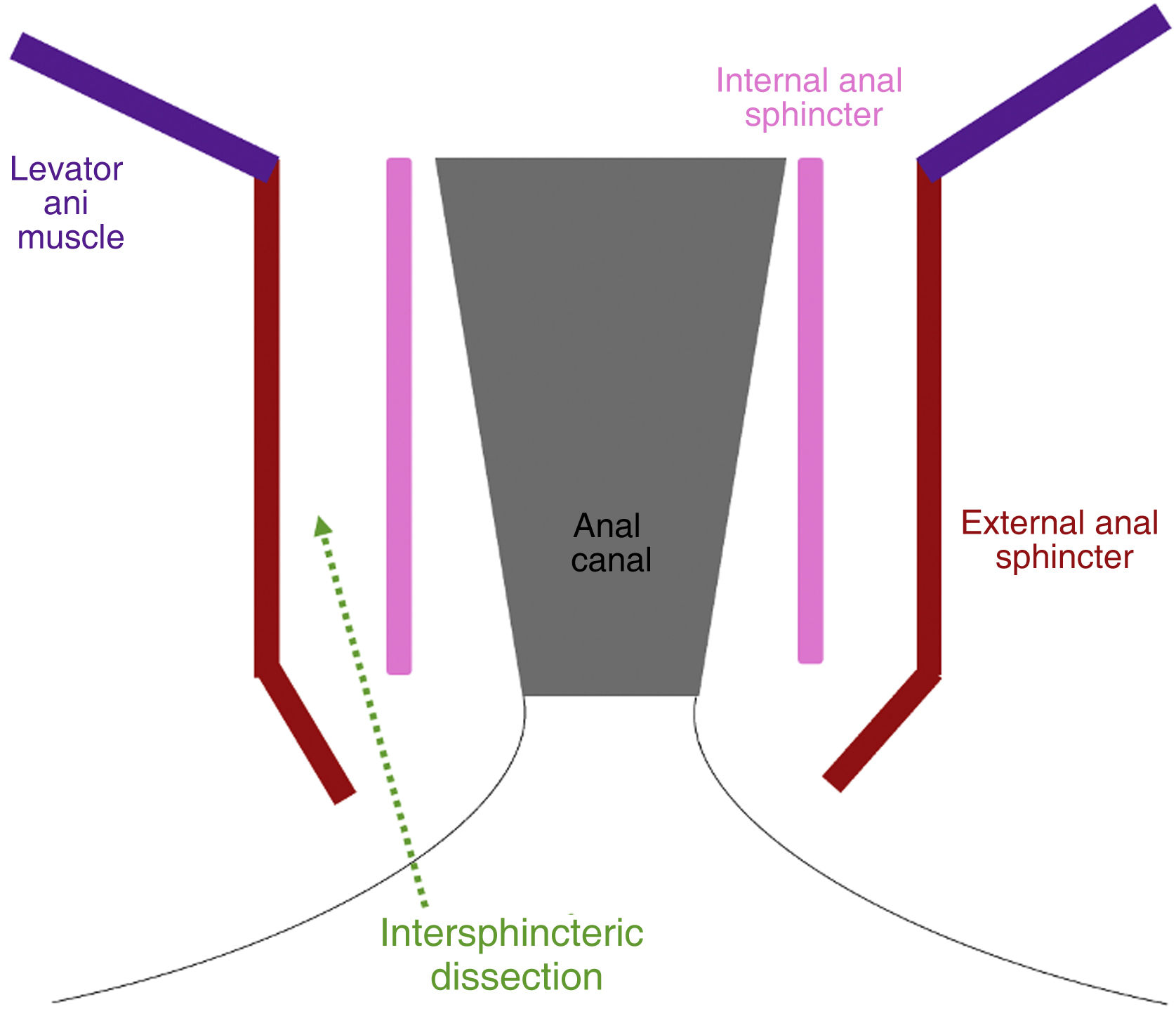

Posterior and lateral dissection of the mesorectum should be similar to the TME technique in order not to leave too much of the mesorectal remnant in the pelvis.5 An appropriate anatomical approach is essential to avoid injury to the superior hypogastric plexus and bilateral hypogastric nerves.2 It should begin with the identification of the superior rectal artery, continuing with the dissection between it and the promontory to slide through the presacral space to the rectosacral fascia (Fig. 2).2,5 After dissection, Waldeyer’s fascia and the levator ani plane are reached (Fig. 3).2,5

Diagram of the dissection plane of the near-total mesorectal excision (black dashed line) used in the Near-TME laparoscopic approach. The vesical nerve is observed with a nerve trunk that rapidly divides into 2 branches: the vaginal nerve, which innervates the uterus and vagina; and the superior rectal nerve, which innervates the upper part of the anterior surface of the rectum. The posterior vaginal branch leads to the posterior vaginal wall, whose branches cross the rectovaginal septum and are distributed to the anterior rectal wall.

The landmark used for posterolateral dissection is the ureterohypogastric fascia, which contains the ureters and hypogastric nerves on each side.6 Once identified, the dissection is performed between it and the mesorectal fascia.7 If this fascia is identified bilaterally, we will observe a single fascia that continues presacrally.5 This element allows us to preserve the superior hypogastric plexus and both hypogastric nerves (Fig. 4).2,8

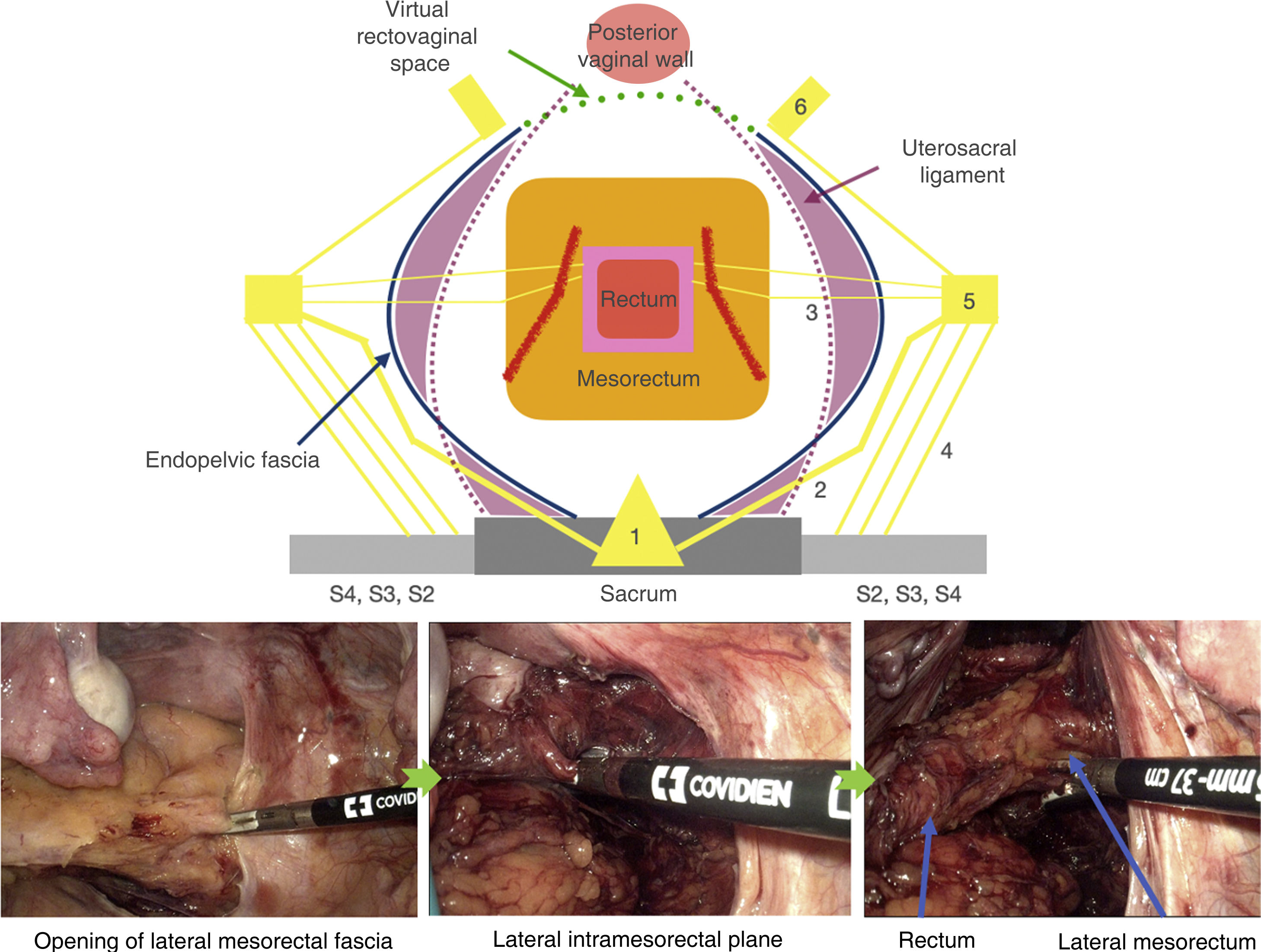

The lateral dissection begins where the posterior dissection encounters the lateral ligaments of the rectum.5 Lympho-fatty tissue encompasses the middle rectal artery (present in 30–40%) and nerve branches from the inferior hypogastric plexus to the rectum or rectal nerves.2,6

The presence of the lateral ligaments indicates where to initiate the intramesorectal dissection up to the rectal wall, thereby reducing the risk of injury to the inferior hypogastric plexus.2,8

The anterior dissection of the rectum begins with the opening of the pouch of Douglas and the beginning of the rectovaginal septum.4 Although the rectovaginal septum needs to be divided, the uterosacral ligament can be preserved if it does not hinder dissection or access to the rectovaginal space.4 The anterolateral dissection is trans-mesorectal up to the rectal muscle wall (Fig. 5).4 In this manner, both pelvic plexi are preserved with their anterior connections to the mesorectum.4

Lastly, the lateral and anterior perirectal dissection is continued up to the plane of the levator ani muscle.9 The perineal stage concludes with proctectomy after accessing the supralevator plane through perianal intersphincteric dissection (Figs. 6 and 7).2

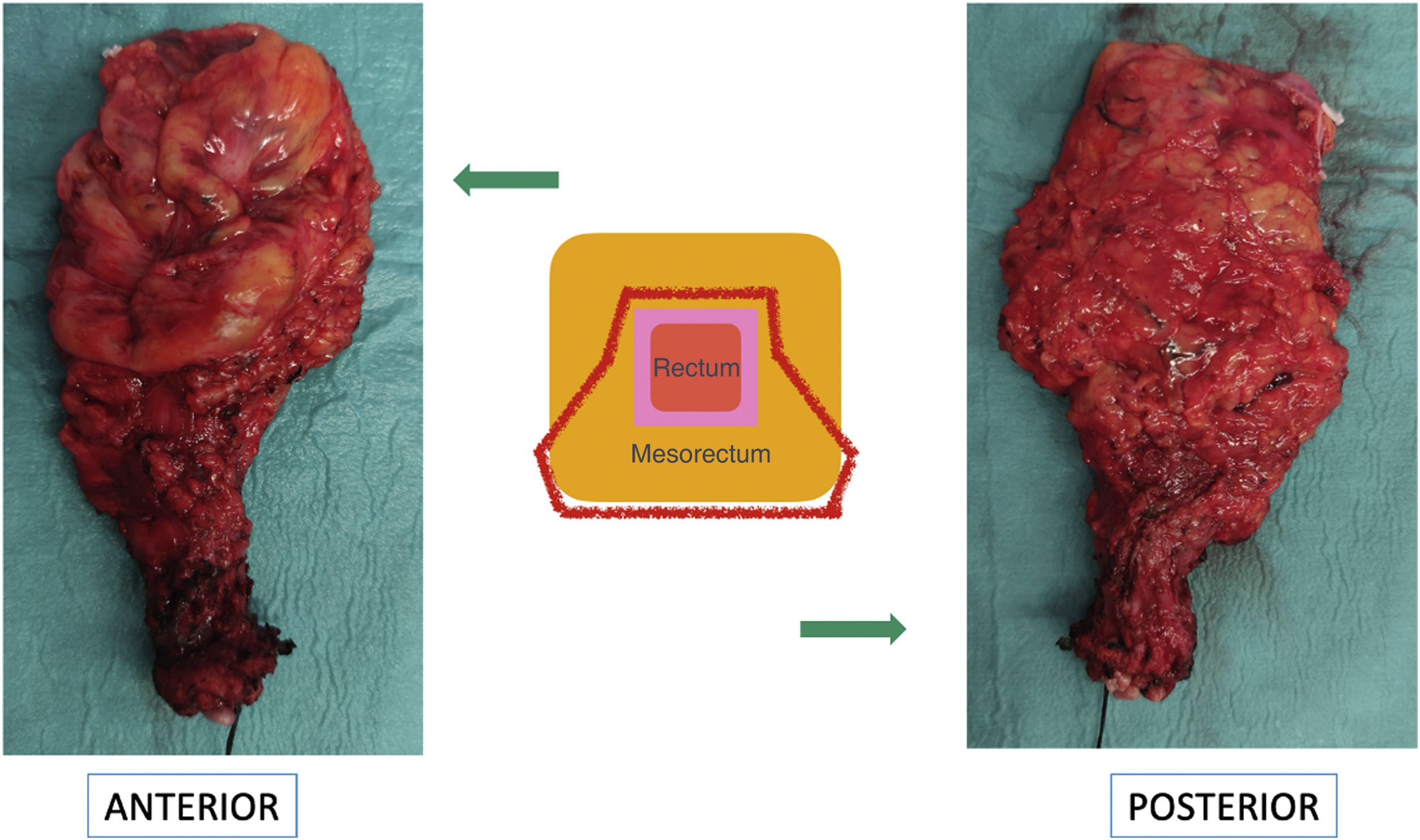

On its posterior side, the surgical piece demonstrates a dissection plane similar to that of TME, while on the anterolateral plane it is similar to that of CRD (Fig. 8). Perineal reconstruction was performed on 3 planes with approximation of the puborectalis muscle, external sphincter muscle and skin.

The patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day with no complications. Over the course of a one-year follow-up, she presented no alterations in sexual or genitourinary function.

DiscussionThree surgical techniques have been described for proctectomy in UC: TME, CRD and Near-TME.1,10

The advantage of TME in ulcerative colitis is that it is a continuation of the surgical planes that colorectal surgeons are already familiar with in rectal cancer surgery. Furthermore, it avoids the pelvic mesorectal remnant, which is associated with malfunction of the ileoanal reservoir due to its proinflammatory activity.6,10 On the downside, TME increases the risk of pelvic autonomic nerve injury.2,5

CRD reduces the risk of nerve injury, but the mesorectal remnant is associated with the aforementioned disadvantages.1 Nevertheless, some authors have linked the persistence of this remnant with a decrease in postoperative complications.11 In addition, CRD increases the risk of intraoperative rectal bleeding and perforation.1,10

Our working group has recently standardized the Near-TME technique,10 both for proctectomy in UC with or without creating an ileoanal reservoir.

This description and protocol have come about for 2 reasons. The first is due to the recommendation by clinical guidelines to perform a posterior dissection similar to TME, but anterolateral similar to CRD, without clearly indicating how to carry this out. The second is the lack of consensus and the different methods described: perimuscular, intramesorectal, trans-mesorectal or mesorectal-sparing proctectomy. This also hinders training in the technique and its implementation, while impairing the evaluation of results.

In Near-TME, it is possible for the specimens to be classified by the pathologist, and prospective studies may thus be carried out with correct methodology.2 If TME has been performed, the surgical piece will show a correct mesorectal plane, both posterior and anterolateral.10 If CRD has been performed, the entire circumference of the rectal muscle plane will be observed.2 Lastly, if Near-TME is performed, the posterolateral mesorectal plane and anterolateral perirectal plane will be observed.2 Therefore, it would not be indicated in patients with a diagnosis of associated cancer.

Until now, the Near-TME technique had been described in men but not in women.2 The landmarks used in men include: the superior rectal artery and the presacral space for posterior dissection; the ureterohypogastric fascia for posterolateral dissection; the lateral ligament of the rectus for lateral dissection; and Denonvilliers’ fascia for anterior dissection.2 The technique also needed to be defined in females due to the dissimilar landmarks that must be used and the different consequences arising from possible pelvic nerve injuries.8

The anatomical reference points that vary in the Female Near-TME technique are found in the anterolateral dissection, which is completely different from the male procedure.6

Likewise, one of the dissimilar structures is the uterosacral ligament, which is the result of embryological tissue reinforcing the endopelvic fascia.4

The main difference, however, lies in the presence of Denonvillier’s fascia in males, resulting from the embryological adhesion of the 2 mesothelial layers of the peritoneal sac.4 In females, this adhesion also occurs, but the resulting fascia adheres to the posterior vaginal wall, becoming part of it in adulthood.4 The portion of this adhesion that lies between the pouch of Douglas and the posterior vaginal wall is the beginning of the rectovaginal septum. Therefore, the anterior dissection of the Female Near-TME begins with the division of the pouch of Douglas, continues with the beginning of the rectovaginal septum, and ends with the anterior mesorectum up to the rectal muscle wall.4

There are identical critical areas of potential nerve injury in both males and females:6 the superior hypogastric plexus and hypogastric nerves during dissection of the posterior mesorectum; pelvic splanchnic nerves during posterolateral dissection at S3-S4; and the inferior hypogastric plexus during lateral dissection.2,5,8

In women, the pelvic plexus and its branches are located lateral to the cervix and the lateral vaginal fornix, in the paracervix.6,12 At the intersection of the ureter and the uterine artery, we encounter a nerve trunk that rapidly divides into 2 branches: the vaginal nerve, which innervates the uterus and vagina; and the superior rectal nerve, which innervates the upper part of the anterior surface of the rectum.13 The posterior vaginal branch passes in the direction of the posterior vaginal wall, whose branches cross the rectovaginal septum and are distributed to the anterior rectal wall.13

Possible alterations of the genitourinary and sexual function as the result of injury to the different female nerve regions are described below.

Injury to the sacral splanchnic nerves can result in detrusor denervation and decreased bladder sensation, resulting in urinary retention and overflow incontinence.8 Dissection of the retrorectal space can cause damage to the superior hypogastric plexus and/or hypogastric nerves, causing reduced bladder capacity and urge incontinence.6,8

Anterolateral dissection is the area most vulnerable to possible autonomic nerve damage,6 which can damage the inferior hypogastric plexus and efferent pathways, leading to urinary incontinence, voiding dysfunction and bladder irritation.8

Female patients present much less pronounced sexual manifestations of autonomic nerve damage, which is more difficult to define.1 These lesions can cause vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, irritative leucorrhea, malodorous discharge and changes in genital sensitivity.8,14

Possible sexual and urinary dysfunction should be assessed with questionnaires that have been validated for this purpose. In the present study, this was done during an interview at a follow-up appointment.

ConclusionThe Near-TME technique in proctectomy for UC decreases the possibility of pelvic nerve injury and reduces the pelvic mesorectal remnant.2,3,8 The anatomical landmarks vary between men and women, especially in the anterolateral hemicircumference.2 The procedure should be conducted by surgeons with experience in inflammatory bowel disease surgery who have extensive knowledge of surgical anatomy.1,14

Conflict of interestThe authors confirm the absence of conflict of interest and the absence of any funding for this case.