Gastric carcinoid tumors (GCT) are benign neuroendocrine cell tumors of the glands of the body and fundus of the stomach. Some 70% of these tumors are located in the digestive tube (more in the small intestine and appendix). The probability of lymph node invasion depends on tumor size: 2% in tumors smaller than 1cm, between 10% and 15% in those measuring 1–2cm, and 60%–70% in tumors larger than 2cm.1–4 The most frequent locations are the body and fundus of the stomach; when there is associated pernicious anemia, 50% are multifocal. Treatment depends on size, possibility of lymph node involvement and whether there are multiple foci. In our case, in a patient who was a candidate for bariatric surgery, preoperative gastroscopy revealed a gastric wall lesion, whose final pathology was GCT. Gastroscopy before bariatric surgery can significantly reduce the number of potentially malignant gastric lesions, which may inadvertently remain in the gastric remnant in cases of bypass surgeries without gastric resection, such as gastric bypass.3

The patient is a 28-year-old woman who had been referred to the Obesity Unit due to progressive weight gain after her first pregnancy and failed attempts to lose weight with low-calorie diets and physical activity (weight 110.5, height 152cm, BMI 47). She reported having extrinsic asthma. She provided a gastroscopy report from a study done in another hospital 1 year before, which described a 3mm polypoid lesion in the prepyloric antrum (biopsy: compatible with chronic antral gastritis with intestinal metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori+). After being assessed by the Obesity Unit, she was considered as candidate for bariatric surgery, and preoperative studies were initiated in accordance with the hospital protocol. H. pylori was eradicated.

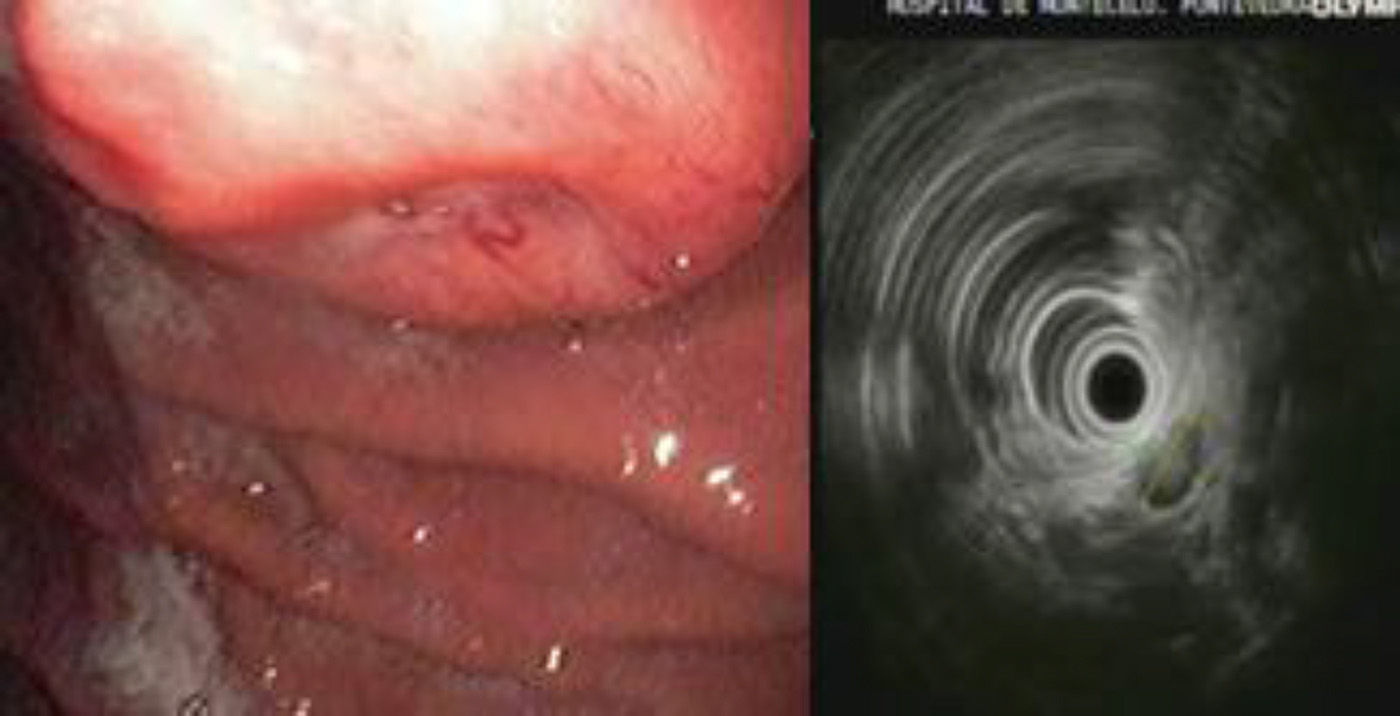

The study of the gastric mass was completed with another gastroscopy, which detected a raised, umbilicated lesion measuring 2cm on the posterior side of the body of the stomach. Biopsy was non-specific. Endoscopic ultrasound showed a subepithelial mass on the posterior side of where the body and fundus meet, with central ulceration and slight depression. In the area of the lesion, a hypoechoic image was observed with central hyperechogenicity; it was round, measured 14mm×10mm, and appeared to depend on the longitudinal portion of the fourth layer or muscularis propria (Fig. 1).

The remaining preoperative studies showed no notable alterations.

The case was discussed with the Digestive Department, and the most probable diagnosis of the lesion was thought to be a 1.4cm GIST tumor. Its location would enable a vertical gastrectomy to be done with resection of the lesion in the gastrectomy specimen as it seemed to be located on the posterior side toward the greater curvature of the stomach at the junction of the body and fundus.

The findings from the gastroscopy and endoscopic ultrasound were explained to the patient. Bariatric surgery was proposed, including resection of the gastric mass. The most likely surgical options would be either vertical sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass with gastric resection, and we explained to the patient that the final technique would depend on the intraoperative findings.

The surgical intervention was begun with exploratory laparoscopy, exposing the posterior gastric side with aperture of the gastrocolic ligament. We found lymphadenopathies that were stone-hard in appearance in the region of the left gastric blood vessels (Fig. 2). Lymphadenopathies were sent for intraoperative pathology diagnosis, and intraoperative gastroscopy was carried out. By means of a combine vision provided by the gastroscope and laparoscope, the lesion was identified in the lesser curvature of the stomach 4cm from the cardias (this differed from the preoperative gastroscopies). The pathology diagnosis of the lymphadenopathies was metastatic carcinoid tumor, so we assumed that the gastric lesion was the primary carcinoid tumor. Given the suspected diagnosis of GCT with lymph node infiltration near the cardias, we decided to perform total laparoscopic gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction with a 100cm intestinal loop. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the 4th day post-op.

The definitive pathology study reported a well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasm (carcinoid tumor) that infiltrated the muscularis mucosae and submucosal areas. In the gastric antrum, there were changes compatible with chronic gastritis and areas of intestinal metaplasia. Chronic lymphadenitis was evident in 15 lymph nodes of the lesser curvature as well as 12 in the region of the hepatic pedicle, and 1 lymph node presented metastatic infiltration of a carcinoid tumor (1/27).

After 24 months of follow-up, the patient weighed 74kg, with a BMI of 32kg/m2. She presented a good general condition and had negative radiological and analytical tests (with chromogranin A) for tumor recurrence.

This case demonstrated the importance of an adequate study with preoperative gastroscopy prior to bariatric surgery, especially if a bypass technique is going to be used without gastric resection, such as gastric bypass (which would have been our technique of choice with a BMI above 45 and no risk factors). With this type of surgery, there is the risk that a premalignant lesion may inadvertently remain in the excluded gastric remnant, which would have been difficult to access after the procedure. The diagnosis of premalignant lesions, such as metaplasia, polyps, atrophic gastritis, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, carcinoid tumor, etc., may allow for some lesions to be treated endoscopically or may lead to a change in the surgical technique in cases in which gastric resection should be used.

Please cite this article as: Ballinas Miranda JR, Estevez Fernandez S, Mariño Padin E, Carrera Dacosta E, Sanchez Santos R. Tumor carcinoide en obesidad mórbida. Cambio del planteamiento quirúrgico previo dependiendo de los hallazgos intraoperatorios. Cir Esp. 2015;93:348–350.