Bull gore injuries (cornadas) are the most frequent injuries caused by bulls during bull-related events. Blunt trauma caused by being struck by the bull's horns and/or head (known as varetazos) usually causes less serious injuries. We present the case of a patient who received blunt trauma from a bull horn, that caused diaphragm rupture and right hepatic avulsion requiring right hepatectomy, vena cava repair and diaphragm suture.

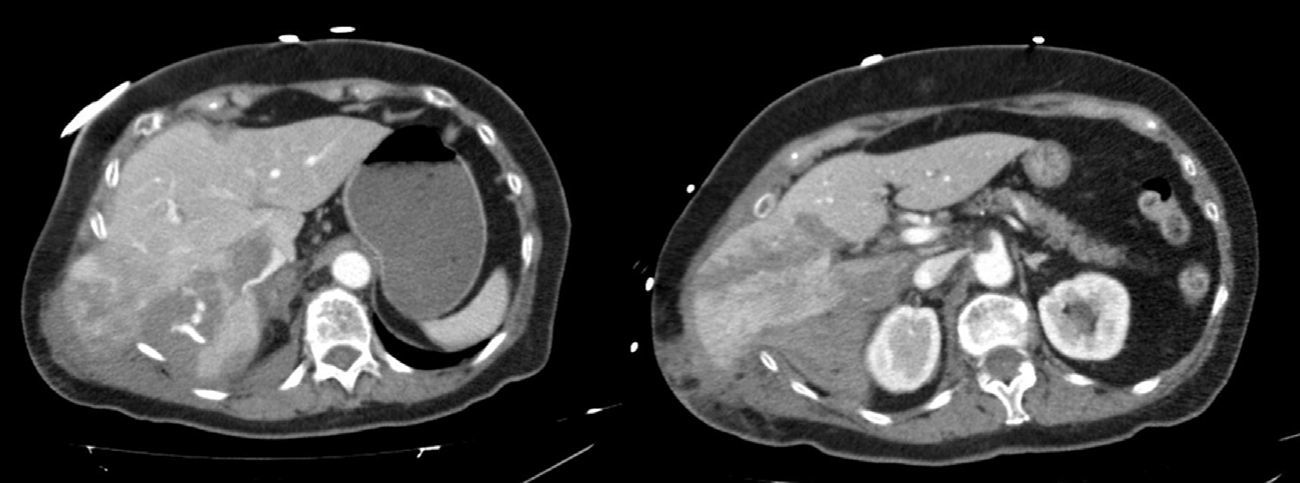

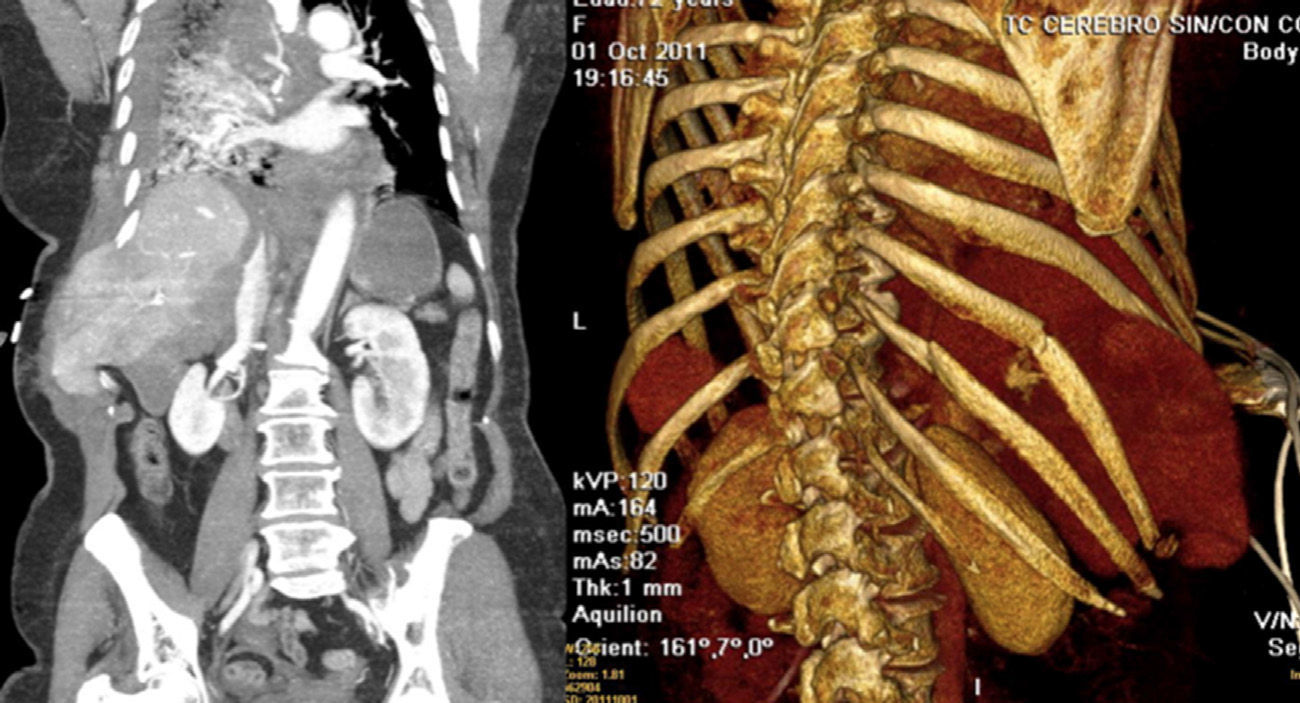

Case ReportThe patient is a 72-year-old woman who was brought to our Emergency Department after blunt thoracoabdominal trauma that occurred during a bull running event. The bull had struck the patient on the right flank with its head and horns. The patient was pale, hypotensive (80/50mmHg) and hypothermic (35.8°C). Glasgow Coma Scale was 15; initial hemoglobin was 8.1g/dl. Examination detected a large hematoma that was painful to the touch in the right hemithorax and guarding in the right hypochondrium. After initial resuscitation measures, a CT scan revealed 4 right rib fractures (7th to 10th), liver trauma with active bleeding (AAST grade V) and liver herniation in the right thorax (Figs. 1 and 2). Given these radiological findings and the unstable clinical situation of the patient, we decided on emergency surgery.

During surgery, we observed: a large hemoperitoneum, right diaphragm rupture, herniation of the liver into the thorax, retroperitoneal hematoma, complete avulsion of segments VI and VII and partial avulsion of V and VIII, a large laceration affecting segments V and IVb, and several tears on the anterior side of the vena cava caused by rupture of the veins draining segments 6 and 7. We performed right atypical hepatectomy, suture of the multiple orifices present in the inferior vena cava, hepatorrhaphy of the liver laceration, suture of the diaphragm and placement of a right thoracic drain. Probably due to the transfusion of 6 blood and 2 plasma units, we were not able to achieve perfect hemostasis and we decided to use temporary packing.

In the beginning, the patient remained hemodynamically unstable, with mixed shock (hypovolemic and distributive) with good response to blood volume expansion and amines. Seventy-two hours later, when the patient was stable and coagulopathy was resolved, the perihepatic packing was withdrawn without complications.

Afterwards, the patient's progress was very torpid and complicated with right basal pneumonia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. We used tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation disconnections, which were poorly tolerated. The patient presented tracheobronchitis due to Stenotrophomona maltophilia, which impeded respiratory improvement. Dynamic radioscopy of the diaphragm confirmed right diaphragmatic paralysis. Ventilatory mechanics improved progressively, with decannulation after 40 days. The patient was moved to the hospital ward after 45 days and discharged from the hospital after 50 days.

The medical literature about bull-related injuries is very limited.1 In Spain, these trauma injuries are classified as either varetazo (caused when the subject is struck with by the bull's head/horns) or cornada (gore injury caused by the horns). The lesions are usually complex for several reasons: several injury mechanisms may interact; several wound paths may be found due to the circular movements of the animal while goring; there may be a large amount of tissue damage and/or foreign bodies lodged in the wounds; and, wound contamination is always a factor.1,2 The depth of gore wounds (cornadas) depends on the penetrating force of the horn into the patient as well as the weight and speed of the animal.1,2 Injuries caused by horn/head impact (varetazos) convert kinetic energy into potential energy and may involve injuries that are not initially diagnosed.1

Bull-related trauma usually affects young males (97%).2 The most frequent location for gore injuries are the lower extremities (60%), followed by the perineal region.1,2 The abdomen is only affected in 10% of these situations.2 In a series of 387 bull-related injuries, only 3 patients required laparotomy for liver injuries, requiring 2 liver sutures and one packing with later hepatectomy.2 Therefore, serious liver injuries caused by bulls are extremely rare, and even more so in 70-year-old women like our patient.

The main therapeutic goal in blunt abdominal trauma involving the liver should be hemorrhage control.3 Injuries to the posterior side of the liver, retrohepatic vena cava (as in our patient), and avulsion of the suprahepatic veins or branches of the caudate lobe are injuries that are difficult to treat and have a high mortality rate.3

When associated with extensive parenchymal injuries and uncontrolled bleeding, major liver trauma may rapidly develop a lethal triad of acidosis, hypothermia and coagulopathy.4 In these cases, the use of packing has been established as the technique of choice.4 The most frequent complications of packing are rebleeding or the reduced flow of the inferior vena cava.3,4 The number of major hepatectomies due to liver trauma has dropped drastically. Currently, the indications are very restricted and early packing is the best choice if the injuries to the retrohepatic vena cava are not very extensive.3,4 We decided to perform hepatectomy for 3 reasons: it provided better access to the multiple lesions of the vena cava, we were able to eliminate the large quantity of devitalized tissue and, in addition, the extensive diaphragm injury did not allow us to use packing early on.

Traumatic diaphragm rupture is an unusual complication that occurs in 7%–15% of patients with severe thoracoabdominal trauma.5 The causal mechanism in blunt trauma is a high-energy impact that produces acceleration–deceleration forces.5 Traumatic diaphragm rupture caused by bull-related trauma is extremely rare. Herniation of abdominal organs to the thoracic cavity occurs in 20% of right-side diaphragm rupture, as happened in our patient. Diagnosis is difficult and requires a high index of suspicion. CT presents a diagnostic specificity close to 100%.5 Patients with traumatic diaphragm rupture usually present other associated injuries.5 Repair of the diaphragm is done by suture with non-absorbable material as well as the placement of a thoracic tube. In very large defects, it may be necessary to use mesh.5 Few patients present post-suture functional paralysis, which may occasionally require the insertion of a pacemaker. Our patient developed temporary diaphragm paralysis that did not require a pacemaker.

Please cite this article as: Ramia JM, de la Plaza R, Benito C, Quiñones JE, García-Parreño J. Traumatismo hepático grave y rotura diafragmática en encierro taurino. Cir Esp. 2015;93:350–352.