Indocyanine Green is a fluorescent substance visible in near-infrared light. It is useful for the identification of anatomical structures (biliary tract, ureters, parathyroid, thoracic duct), the tissues vascularization (anastomosis in colorectal, esophageal, gastric, bariatric surgery, for plasties and flaps in abdominal wall surgery, liver resection, in strangulated hernias and in intestinal ischemia), for tumor identification (liver, pancreas, adrenal glands, implants of peritoneal carcinomatosis, retroperitoneal tumors and lymphomas) and sentinel node identification and lymphatic mapping in malignant tumors (stomach, breast, colon, rectum, esophagus and skin cancer). The evidence is very encouraging, although standardization of its use and randomized studies with higher number of patients are required to obtain definitive conclusions on its use in general surgery.

The aim of this literature review is to provide a guide for the use of ICG fluorescence in general surgery procedures.

El verde de indocianina es una tinción fluorescente visible con luz cercana al infrarrojo. Es útil para la identificación de las estructuras anatómicas (tracto biliar, uréteres, paratiroides, conducto torácico), la vascularización de tejidos (en anastomosis en cirugía colorrectal, esofágica, gástrica, bariátrica, para plastias y colgajos en cirugía de pared abdominal, hepática, en hernias estranguladas en la isquemia intestinal), para la identificación de tumores (hígado, páncreas, suprarrenal, implantes en la carcinomatosis peritoneal, tumores retroperitoneales y linfomas) y para la identificación del ganglio centinela y del mapeo linfático de tumores malignos (cáncer de estómago, mama, colon, recto, esófago y piel). Las evidencias son muy alentadoras, aunque se necesita la estandarización de su uso y más estudios prospectivos y aleatorizados con mayor número de pacientes para obtener conclusiones definitivas sobre su uso.

El objetivo de esta revisión de la literatura es proveer una guía para el uso de la fluorescencia con verde de indocianina en procedimientos de cirugía general.

Fluorescence is a form of luminescence that distinguishes substances that can absorb energy in the form of electromagnetic radiation, and then emit some of that energy in the form of the same radiation, but at a different wavelength.1

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a visible fluorescent tricarbocyanine dye with near infra-red (NIR) or laser systems, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1956.2

ICG fluoresces when activated with NIR, with absorption and emission peaks at 805−835 nm, respectively.2,3 The fluorescence is detected using specific cameras that transmit this signal to a monitor, through which the structures in which the dye is found can be identified.3

After intravenous administration, ICG binds rapidly to plasma proteins and is eliminated unchanged by bile, with no enterohepatic recirculation, with a plasma half-life of 3−5 min and hepatic metabolism.2,3 When injected directly into tissue, ICG binds to proteins and reaches the nearest lymph node within minutes, then binds to regional lymph nodes 1−2 h after injection.3

Fluorescence has become widely used in general surgery over recent decades, particularly in minimally invasive surgery, due to the optical system and light sources required for the laparoscopic or robotic approach.3–8

The aim of this literature review is to provide guidance on the use of fluorescence in surgical procedures and to analyse its main applications in general surgery.

Method for using indocyanine greenPreparation of indocyanine greenICG is usually administered diluted with distilled water.3,6,9–12 ICG is diluted with albumin when used to identify the tumour draining sentinel lymph node.9,10 Its use with albumin is due to its ability to stop in that first draining lymph node and be successfully identified.9,10 This drug should not be diluted with saline solutions (saline, Ringer's solution), as this could lead to precipitation of the dye.4

Administration routeDifferent routes can be used to administer ICG, depending on the structures to be visualised.3,7,13–18 The intravenous route is used to identify the vascularisation of tissues intraoperatively, to perform anastomosis or to identify tissues with hypoperfusion or ischaemia, it is also used to identify tumours or different anatomical structures.3,7,13,14 For sentinel node detection or lymphatic mapping during lymphadenectomy in the case of malignant neoplasms,9,10 for example in the case of gastrointestinal tumours, ICG can be administered peritumourally in the submucosal or subserosal layer of the intestinal wall.15,16 ICG can be administered directly into the gallbladder, to identify the biliary tree, or into the ureters.17,18

Contraindications for indocyanine green injection and toxicityCare should be taken in patients with hypersensitivity to sodium iodide, allergic to iodine, with clinical hyperthyroidism, autonomous thyroid adenomas and focal and diffuse autonomous disorders of the thyroid gland, in patients with liver disease and during pregnancy.3,4 The lethal toxic dose observed in rats for intravenous administration is 87 mg/kg body weight and for intraperitoneal administration in mice is 650 mg/kg body weight. 4 No adverse effects or cases of overdose of the drug or abnormal laboratory parameters because of overdose in humans have been reported to date.3,4

Detection systemsVisualisation of the fluorescence emitted by ICG requires a detection system comprising a spectrum-resolving light source, light-collection optics with special filters, and a camera prepared for it, as well as control software and hardware for computing, input, and display. To obtain fluorescence, ICG molecules must be illuminated by NIR or laser light with an infrared filter.19,20

The recent development of a new technology enables intraoperative detection of the fluorescence emitted by ICG in overlay mode.21,22 This display mode is composed of both the standard white light image and the superimposed NIR light.21,22 Compared to the former NIR visualisation technology, where only fluorescent structures were visualised, the overlay images allow surgery to be performed with support directly with fluorescence, without switching to white light by visualising fluorescent and non-fluorescent structures at the same time, like augmented reality.21,22

One of the limitations of this technology is the surgeon's subjective assessment of fluorescence uptake during surgery.23–31 Although several reviews and meta-analyses have been published in the literature, subjective assessment of fluorescence is still considered a bias because of the heterogeneity of fluorescence.25–27 Therefore, to quantify fluorescence, several types of software have recently been proposed for objective assessment of fluorescence and more reliable assessment of tissue perfusion.23–31 These software programmes process the fluorescent signal by generating a fluorescence-time-curve (FTC), yielding a number of different parameters that reflect tissue perfusion.25,28 However, several factors can influence the amount of fluorescence, such as plasma ICG concentration, systemic perfusion factors (including blood pressure, cardiac output and vasoconstriction) and different detection systems. Despite encouraging results in plastic surgery, ophthalmic surgery, and neurosurgery, published studies are very heterogeneous, and there is no current gold standard methodology.25,30,31 Pending technological developments in fluorescence quantification, it appears that fixed ICG dosing per kg of body weight for each patient, stable fixed NIR camera configuration and systemic perfusion factors are essential for homogeneous quantification.25

Identification of anatomical structuresBiliary tractICG fluorescence imaging allows intraoperative real-time virtual cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and avoids situations of potential risk of bile duct injury.13,14,17,32–47

ICG, by concentrating at the hepatic level and being excreted into bile, allows the anatomy of the biliary tree to be drawn. The use of ICG to identify the bile duct has been evaluated in multiple studies that have demonstrated high detection rates of the cystic duct, up to 100%,13,32,33 although these detection rates are lower in cases of acute cholecystitis, due to the inflammatory process.13,14,17,32–47

The strong fluorescence of the liver may prevent or hinder identification of the biliary tree, suggesting it should be injected 12−24 h before surgery.13,14,17,32–47 It is true that with the new imaging systems, with advanced visualisation systems, it is possible to work with infrared light without changing to a black/white system, facilitating identification of the biliary tract without excessive disturbance from the strong fluorescence of the liver.13,14,17,32–47 However, intravesicular injection has also been proposed to avoid this problem,13,14,17,32–47 although the disadvantage with this system is that a stone in the cystic duct can block its diffusion and if the ICG is spilled, its intraoperative use can be difficult.13,14,17,32–47

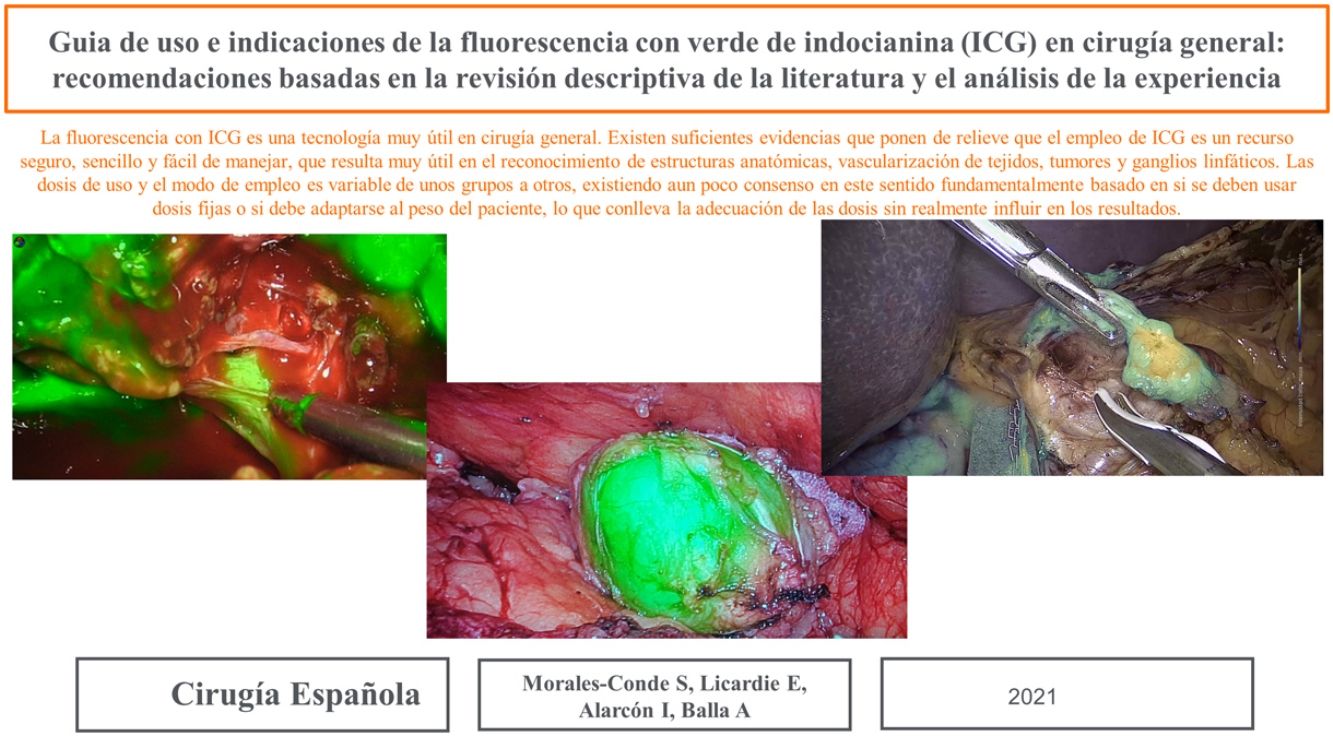

The dose and administration of ICG for fluorescence identification of the bile duct is discussed in Table 1. Our method is to inject it intravenously at the time of anaesthetic induction (20−30 min prior to surgery) at a pre-set dose of 15 mg of ICG diluted in 3 cm3 of distilled water (Fig. 1).

Dose and administration route of indocyanine green (ICG) to assess anatomical structures.

| Authors | N. of patients | Solution | Dose | Administration route | Time of administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biliary tract | |||||

| Boni et al.13 | 52 | Saline solution | .4 mg/kg | Intravenous | 14 ± 9 min before surgery |

| Graves et al.17 | 11 | Sterile water | .025 mg/ml (1 ml) | Intravesicular | During surgery |

| Dip et al.33 | 45 | n.s. | .05 mg/kg | Intravenous | 60 min before surgery |

| Schols et al.34 | 30 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | At anaesthetic induction |

| Buchs et al.36 | 23 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | 30−45 min before surgery |

| Quaresima et al.37 | 44 | Sterile water | .1 ± .1 mg/Kg | Intravenous | 10.7 ± 8.2 h before surgery |

| Lehrskov et al.39 | 60 | n.s. | .05 mg/kg | Intravenous | At anaesthetic induction |

| Hiwatashi et al.40 | 65 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | 2 h before surgery |

| Daskalaki et al.41 | 184 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | 45 min before surgery |

| Dip et al.42 | 321 | n.s. | .05 mg/kg | Intravenous | 45 min before surgery |

| Broderick et al.43 | 400 | Sterile water | 7.5 mg in total | Intravenous | 45 min before surgery |

| Bleszynski et al.44 | 108 | n.s. | 4 mg in total | Intravenous | At anaesthetic induction |

| Liu et al.46 | 46 | n.s. | .125 mg/ml (10 ml) | Intravesicular | During surgery |

| Gené Škrabec et al.47 | 20 | Sterile water | .25 mg/ml (Sterile water 1 ml + 9 ml Bile | Intravesicular | During surgery |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | Dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | At anaesthetic induction (20−30 min before surgery) |

| Ureters | |||||

| Siddighi et al.18 | >10 | Sterile water | 25 mg in 10 ml per side | Ureteral catheter | Before surgery under general anaesthetic |

| Mandovra et al.50 | 30 | Sterile water | 5 mg in 2 ml per side | Ureteral catheter | Before surgery under general anaesthetic |

| Ryu et al.51 | 7 | n.s. | n.s. | Ureteral catheter | Before surgery under general anaesthetic |

| White et al.52 | 16 | n.s. | 2.5 mg/ml per 5 ml per side | Ureteral catheter | Before surgery under general anaesthetic |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice53 | – | Sterile water | Filling of catheter with a dilution of 25 mg/5 cm3 | Ureteral catheter | Before surgery when under general anaesthetic |

| Parathyroid glands | |||||

| Van den Bos et al.55 | 30 | Sterile water | 2.5 mg/ml (3 ml) | Intravenous | 1. Before removal of hemithyroid2. After removal of hemithyroid |

| Razavi et al.56 | 43 | n.s. | 5 mg | Intravenous | At the end of the surgery |

| Rudin et al.57 | 86 | n.s. | 3 ml | Intravenous | During surgery |

| Papavramidis et al.61 | 60 | n.s. | 5 mg (1 ml) | Intravenous | 1. After removal of the thyroid |

| Alesina et al.62 | 5 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | 1. After mobilisation of the thyroid gland under autofluorescence without ICG2. With administration of ICG |

| Lerchenberger et al.63 | 50 | Sterile water | 5 mg (1 ml) | Intravenous | 1. After mobilisation of the thyroid gland under autofluorescence without ICG2. With administration of ICG |

| Thoracic duct | |||||

| Vecchiato et al.64 | 20 | Saline solution | .5 mg/kg | PercutaneouslyBilaterally in the superficial inguinal nodes | Before thoracoscopy in total oesophagectomy, and then laparoscopy in Ivor Lewis oesophagectomy |

| Chakedis et al.65 | 6 | Saline solution | 2.5 mg/ml (1−2 ml) | Subcutaneously on the dorsum of the left foot | 15 min before level IV neck dissection |

n.s., not specified.

Ureter damage has been described during colorectal surgery, with an incidence of .15% to .66%.48 Different methods have been used to identify the ureters, such as prophylactic ureteric stents.49 However, this type of device is not without risks, including ureteric damage, haematuria, urinary tract infections, and impossibility of passing a stenosis.49

To identify the ureters, ICG is injected by inserting of the tip of a catheter into the ureteral orifice by cystoscopy in the same surgical act under general anaesthesia before starting the procedure, which can reduce iatrogenic complications by not forcing entry, and enable them to be filled with ICG even if there is a partial stenosis, as the liquid can pass it, and thus they can be identified.18,50–53 This method is used because ICG is eliminated via the hepatic route, and therefore does not reach the ureter as it is administered intravenously (Table 1).2,3,18

Our method consists of a catheter placed by the urology department at the entry of the ureters to the bladder and filling them with a dose of 25 mg in 5 cm3 of distilled water, closing the catheter during surgery and the urine around the catheter can drain into the bladder (Table 1).53

Parathyroid glandsICG fluorescence can be useful to identify the parathyroid glands during thyroid surgery.54–58 It has been observed recently that autofluorescence (AF) of the parathyroid glands, without the need to administer ICG, can be very useful for identification using near-infrared devices at approximately 2–3 cm.59,60 It has been reported that AF can be up to 96%–98% effective in identifying the parathyroid.59,60 However, most authors state it is most useful for verifying the identification and vascularisation of the glands once the surgeon has already located them, and therefore AF can be useful as an intraoperative anatomical confirmation tool and for assessing and predicting postoperative hypocalcaemia (Table 1).59,63

Thoracic ductICG fluorescence can be used to identify the thoracic duct (TD).64,65 Injury to the TD can occur during oesophagectomy, neck dissection or lung surgery and the development of chylothorax is feared as a surgical complication.64,65 Subcutaneous injection of ICG near lymph node stations may help detect the TD intraoperatively to avoid iatrogenic injury (Table 2).64,65

Dose and administration route of indocyanine green (ICG) for tissue perfusion assessment.

| Authors | N. of patients | Solution | ICG dose | Administration route | Time of administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal surgery | |||||

| Boni et al.3 | 107 | Soluble water | .2 mg/kg | Intravenous | After section of the mesentery, before anastomosis |

| Gröne et al.71 | 18 | n.s. | 15 mg in total | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Jafari et al.72 | 139 | n.s. | From 3.75 to 7.5 mg | Intravenous | After mobilisation of the colon and anastomosis |

| Kin et al.73 | 173 | n.s. | 3 ml | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| De Nardi et al.74 | 118 | Sterile water | .3 mg/kg | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section and after anastomosis |

| Kawada et al.75 | 68 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Kim et al.76 | 123 | n.s. | 10 mg in total | Intravenous | After mobilisation of the colon |

| Hasegawa et al.77 | 141 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Ishii et al.78 | 223 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Watanabe et al.79 | 211 | n.s. | .25 mg/kg | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Morales-Conde et al.80 | 192 | Sterile water | 15 mg in total | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Wada et al.81 | 112 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Chang et al.82 | 110 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Tsang et al.83 | 62 | n.s. | 10 mg | Intravenous | . |

| Impellizzeri et al.84 | 98 | S | 12.5 mg in 5 ml | Intravenous | After mobilisation of the colon and ligation of the vessels before colon section |

| Alekseev et al.85 | 187 | n.s. | .2 mg/kg | Intravenous | Before proximal colon section |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | Left/right colon: before proximal colon sectionRight colon/splenic angle: before section of the colon and ileum |

| Oesophageal surgery | |||||

| Kitagawa et al.86 | 46 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before construction of gastric tube and after transposition in the chest |

| Sarkaria et al.87 | 42 | Aqueous solution | 10 in total | Intravenous | Before construction of gastric tube |

| Karampinis et al.88 | 35 | n.s. | 7.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Kumagai et al.89 | 70 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Rino et al.90 | 33 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Yukaya et al.91 | 27 | n.s. | .1 mg/kg | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Zehetner et al.92 | 150 | n.s. | 2.5 in total | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Shimada et al.93 | 40 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Koyanagi et al.94 | 40 | n.s. | From 1.25 to 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Noma et al.95 | 71 | n.s. | 12.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Luo et al.96 | 86 | Sterile water | .5 mg/kg | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube and before transposition in the chest |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | After creation of the gastric tube before final endostapler firing |

| Gastric surgery | |||||

| Huh et al.98 | 30 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After anastomosis |

| Kim et al.99 | 20 | n.s. | 7.5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before anastomosis |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | Before anastomosis |

| Bariatric surgery | |||||

| Ortega et al.100 | 86 | n.s. | 3 ml | Intravenous | After vertical gastrectomy |

| Di Furia et al.101 | 43 | n.s. | 5 ml | Intravenous | After vertical gastrectomy |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | Single dose of 25 mg in 5 cm3 | Intravenous | Vertical gastrectomy: after performing gastric by-pass: after creating the anastomosis |

| Assessment in strangulated hernia | |||||

| Gianchandani Moorjani et al.102 | 3 | n.s. | 10 mg in 2 ml | Intravenous | n.s. |

| Daskalopoulou et al.103 | 1 | n.s. | 3 ml | Intravenous | After hernia reduction in the abdomen |

| Ryu et al.104,105 | 2 | n.s. | 10 mg in 2 ml | Intravenous | After hernia reduction in the abdomen |

| Ryu et al.106 | 1 | n.s. | 10 mg in 2 ml | Intravenous | After hernia reduction in the abdomen |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | Once the strangulated contents have been reduced and the hernia has been repaired |

| Assessment in intestinal ischaemia | |||||

| Karampinis et al.107 | 52 | n.s. | 7.5 mg in total | Intravenous | During exploration of the abdominal cavity |

| Alexander et al.108 | 1 | n.s. | .25 mg in total | Intravenous | During exploration of the abdominal cavity |

| Abdominal wall reconstruction | |||||

| Cho et al.110 | 10 | n.s. | n.s. | Intravenous | After creation of the flap |

| Shao et al.111 | 88 | n.s. | 10 mg in total | Intravenous | After creation of the flap |

| Colavita et al.112 | 15 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before the incision and before skin closure |

| Wormer et al.113 | 46 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | Before the incision and before skin closure |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | Before skin closure |

| Flap assessment for reconstruction in breast surgery | |||||

| Hembd et al.115 | 506 | Saline solution | 7.5 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | 10 to 15 min after vascular anastomosis of the flap |

| Alstrup et al.116 | 77 | Saline solution | 7.5 mg in total | Intravenous | During the operation and after transposition of the flap to the recipient site |

| Chirappapha et al.117 | 29 | n.s. | .25 mg/kg | Intravenous | After completely obtaining the pedicled flap |

| Anker et al.118 | 42 | n.s. | .3 mg/kg | Intravenous | After completion of removal of the flap before section of the pedicle |

| Assessment of the limits of anatomical liver resection | |||||

| Kobayashi et al.120 | 13 | n.s. | 2.5 mg | Intravenous | After ligation of the portal vein |

| 92 | 5 mg indigo carmine | .25 mg | Intraportal | After clamping the right or left hepatic artery | |

| Marino et al.121 | 25 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After clamping the portal Branch of the liver area where the tumour to be removed is located |

| Saline solution | 2.5 mg in total | Intraportal | After clamping the portal artery and vein | ||

| Urade et al.122 | 3 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | After closure of the hepatic pedicle |

| Nishino et al.123 | 10 | n.s. | – | Intravenous | After closure of the hepatic pedicle |

| Xu et al.124 | 27 | Sterile water | 1 ml de .025 mg/ml | Intravenous | After closure of the hepatic pedicle |

| 9 | Sterile water | 5−10 ml de .025 mg/ml | Intraportal | After occlusion of the portal vein or Glisson’s pedicle of the area to be resected | |

| Aoki et al.125 | 14 | n.s. | 1 ml de .025 mg/ml | Intraportal | Percutaneously before the start of surgery |

| Ito et al.126 | 3 | Indigo carmine: 5 ml perflubutane bubbles: .3 ml | .25 mg | Intraportal | Percutaneously before the start of surgery |

n.s., not specified.

Assessment of tissue vascularisation for anastomosis has been demonstrated in different areas of general surgery66 such as colorectal,3,67–85 oesophageal,86–97 gastric,98,99 and bariatric surgery.100,101 It use has also extended to establish the need for bowel resection in strangulated hernias102–106 or to assess the extent of resection in intestinal ischaemia processes in emergency surgery,107–109 to assess tissue viability in hernia surgery and abdominal wall reconstruction,110–113 to assess tissue perfusion in flaps in breast reconstruction,114–118 and for anatomical liver resection.119–126

The dose and form of administration for each of the uses listed below are shown in Table 2.

Tissue perfusion for creating anastomosesThe best time to assess vascularisation in order to create an anastomosis is when the dye first arrives when performing ICG fluorescence angiography (ICG-FA), since ICG is a small molecule, which can diffuse through the submucosal capillary flow over time outside the limits of the ischaemic zones initially delimited by it.127 This phenomenon can lead to a qualitative overestimation of the perfused area when this estimation is based solely on the presence of a fluorescent signal, which can result in confusion and the creation of an anastomosis in poorly perfused tissue.127

The most obvious advantage of the ICG-FA technique is the real-time visualisation of blood perfusion to the tissues.127 However, there are still problems to be solved, such as not allowing evaluation of venous return, which if impaired can also influence the viability of an anastomosis or the development of a subsequent stenosis, or wash-out of the tissues to re-evaluate an anastomotic site.90

Once the vessels and tissues have been dyed, marked enhancement lasts about 5 min, until the liver secretes ICG into intact bile, and it has been established that the wash-out time of the anastomotic site is about 15–20 min to be able to reinject and reassess.2,3

It should be noted that most of the papers mentioned on the use of ICG-FA do not include an objective quantitative assessment of fluorescence angiography.66,80,81 A standardised method to objectively and quantitatively assess anastomotic perfusion could result in further changes in strategy in these patients, but such a widely accepted instrument is not yet available.23,24,80,81,91 Furthermore, quantification would add further value to its re-injection to re-assess perfusion of a specific tissue.23–31

Table 2 shows the doses and administration routes to assess perfusion assessment by different authors. Our group uses a fixed dose of 3 cm3 of distilled water with 15 mg of intravenous ICG in all cases except in bariatric patients and patients with a body mass index greater than 40 kg/m2, where we use a dose of 5 cm3 with 15 mg of ICG. This infusion is performed before section of the colon or ileum in colorectal surgery, before creating the anastomosis in gastric surgery (to assess the duodenal stump and the area where the anastomosis is to be performed), before the last endostapler load while creating the gastric tube in oesophageal surgery (to avoid confusion in interpretation influenced by gastric submucosal vascularisation) and after performing the vertical gastrectomy and anastomosis in gastric by-pass in bariatric surgery to assess the final status of the procedure.

Tissue perfusion to assess viability in emergency surgerya) Strangulated herniaOnly a few cases have been described in the literature on the use of ICG-AF in inguinal and umbilical hernias.102–106 However, the results seem promising, mainly in avoiding unnecessary intestinal resections102–106 (Table 2).

b) Intestinal ischaemiaThe clinical application of ICG-AF during emergency surgery for intestinal ischaemia is being studied.107–109 Karampinis et al. describe a change of surgical strategy in 11.5% of cases107; however, in an experimental study, Seeliger et al. report a discrepancy between mucosal and serosal assessment,109 and further studies are needed to investigate this application (Table 2).

However, it is important to note that in the above-mentioned emergency cases, ICG-AF only assesses arterial ischaemia and not venous ischaemia.90,102–109

Abdominal wall reconstructionICG fluorescence imaging also appears to be useful in reducing complication rates in hernia and abdominal wall reconstruction.110–113

The literature reports the use of ICG-AF in cases of complex abdominal wall reconstruction treated with anterior component separation, showing reduced rates of postoperative skin necrosis and surgical wound infection (Table 2).110–113

Assessment of the flap for reconstruction in breast surgeryFlap necrosis after breast reconstruction is one of the most feared postoperative complications for both the patient and the surgeon, and hypoperfusion is the main cause of flap failure.114–118 ICG-AF allows assessment of flap perfusion and the creation of a more accurate flap, which reduces postoperative complication rates, postoperative imaging studies, follow-up visits, biopsies, and revision reintervention.114–118

Assessing the limits of anatomical liver resectionICG-AF is also useful in identifying hepatic margins for anatomical liver resection in liver tumour and shows promising results.119–126

Several intraoperative strategies have been described to define margins for correct liver resection.119–126 The negative staining technique, after intravenous administration of ICG, after temporary clamping of the portal branch draining the tumour or the parenchyma of the liver region to be removed, identifies the margins of the unstained segment for it to be resected along the demarcation line. The positive staining technique consists of injecting ICG directly into one (single-staining) or more (multiple-staining) portal branches, with the portal artery and veins clamped to avoid washing out the dye. Thus, the liver parenchyma to be removed is fluorescently stained.119–126 In the counterstaining technique, ICG is injected into the portal branch of the liver parenchyma to be preserved.119–126 Another strategy for anatomical liver resection is termed the paradoxical negative staining technique: when the draining hepatic vein is occluded by the tumour, portal flow regurgitation occurs.119–126 In this situation, the regurgitated portal territory shows up as a fluorescence defect even when the portal vein is punctured and ICG is injected (Table 2).119–126

Tumour identificationPrimary liver tumours and liver metastasesICG fluorescence allows the identification of liver lesions.128–136 Healthy liver tissue eliminates ICG within 2h, while peritumoural tissue may retain it due to compression of the bile ducts by the tumour itself, marking a halo that allows identification of the lesion and marking of the resection limits, a circumstance observed in liver metastases.128,129,135 Hepatocellular carcinoma is identified because ICG is retained within the lesion allowing the lesion to be identified (Table 3).128,129

Identification of tumours.

| Authors | N. of patients | Solution | Dose | Administration route | Administration time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary liver tumours and liver metastases | |||||

| Peloso et al.128 | 25 | n.s. | .5 mg/kg | Intravenous | 24 h before surgery |

| Abo et al.130 | 117 | Distilled water | .5 mg/kg | Intravenous | 24 h before surgery |

| Terasawa et al.131 | 41 | n.s. | .5 mg/kg | Intravenous | 3 days before surgery |

| Ishizawa et al.132 | 26 | n.s. | .5 mg/kg | Intravenous | A median of 3 days before surgery |

| Inoue et al.133 | 24 | n.s. | 2.5 mg/2.5 mg | Intravenous/intraportal | After hilum ligation/after ligation of hepatic artery |

| Morita et al.134 | 58 | n.s. | .5 mg/kg | Intravenous | A mean of 14.7 before surgery |

| Lieto et al.135 | 9 | n.s. | .5 mg/kg | Intravenous | 24 h before surgery |

| Yao et al.136 | 18 | n.s. | 2.5 mg/2.5 mg | Intravenous/intraportal | For right hepatectomy: after ligation of right vessels |

| Pancreatic tumours | |||||

| Rho et al.138 | 37 | n.s. | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | During dissection of the uncinate process |

| Hutteman et al.139 | 8 | n.s. | From 5 to 10 mg | Intravenous | After exposure of the neoplasm |

| Newton et al.140 | 20 | n.s. | From 2.5 to 5 mg | Intravenous | 24 h before surgery |

| Paiella et al.141 | 10 | Saline solution | 25 mg in total (5 boluses of 5 mg) | Intravenous | During surgery |

| Shirata et al.142 | 23 | n.s. | 2.5 mg in total | Intravenous | During surgery |

| Adrenal tumours | |||||

| Colvin et al.143 | 40 | n.s. | From 3.8 to 20mg | Intravenous | After exposure of the retroperitoneal space |

| Arora et al.144 | 55 | Distilled water | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | During surgery |

| Sound et al.145 | 10 | Distilled water | From 7.5 to 18.8mg | Intravenous | After exposure of the retroperitoneal space |

| Lerchenberger et al.146 | 3 | n.s. | 5 mg for each adrenal gland | Intravenous | After exposure of the retroperitoneal space |

| Tuncel et al.147 | 8 | Distilled water | 5 mg in total | Intravenous | After exposure of the retroperitoneal space |

| Peritoneal implants | |||||

| Veys et al.150 | 20 | n.s. | .25 mg/kg | Intravenous | After visualising the abdominal cavity |

| Liberale et al.151 | 14 | n.s. | .25 mg/kg | Intravenous | After visualising the abdominal cavity |

| Barabino et al.152 | 10 | Sterile 5% glucose solution | .25 mg/kg | Intravenous | After visualising the abdominal cavity |

| Filippello et al.153 | 10 | n.s. | .25 mg/kg | Intravenous | 24 h before surgery |

| Lieto et al.154 | 4 | n.s. | .25 mg/kg | Intravenous | After visualising the abdominal cavity |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice155 | – | Distilled water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | After visualising the abdominal cavity |

| Retroperitoneal tumours | |||||

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Distilled water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | At anaesthetic induction (20−30 min before surgery) |

| Tissue perfusion for assessment of tissue infiltration – intestinal lymphoma | |||||

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice156 | – | Sterile water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | Once the potential area of lymphoma involvement has been identified |

| Diagnosis of lymphoma and other diseases by biopsy of adenopathies | |||||

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Distilled water | Single dose of 15 mg in 3 cm3 | Intravenous | At anaesthetic induction (20−30 min before surgery) |

n.s., not specified.

The use of ICG fluorescence imaging to identify pancreatic tumours, although not routinely used, appears to be promising.137–142 It has been used to verify complete removal of the mesopancreas in laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomies,137–139 and because complete removal of the retroperitoneal margin is an important prognostic factor, it may be of significant value (Table 3).137

Adrenal tumoursThe adrenal glands (AG) and their anatomical boundaries can be difficult to identify.143–147 The adrenal glands, and the different types of tumours located in them, can be identified based on the difference in perfusion between the adrenal glands and the surrounding tissues.143–147 Adrenocortical tumours are easily recognised by increased fluorescence, however, phaeochromocytomas are hypofluorescent.143–147 This technology may be useful in assessing the blood supply to the remaining adrenal tissue (Table 3).146,147

Peritoneal carcinomatosisPreoperative detection of peritoneal metastases is difficult with current imaging techniques.148–155 Appropriate diagnosis and staging are important in the choice of the best therapeutic option.148–154 It seems that the clinical application of ICG fluorescence in peritoneal carcinomatosis should be reserved for patients with a carcinomatosis index of less than 8, as the value of fluorescence is limited in patients with a preoperative diagnosis of extensive peritoneal metastatic spread.152,153

In patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer, staging and completeness of cytoreductive surgery are important prognostic factors.152 Fluorescence-guided imaging may be a tool to facilitate intraoperative assessment of undetected tumour margins and implants beyond the current methods of palpation and visual inspection.148–155

Most reported studies, after clinical exploration of the abdominal cavity, administered 0.25 mg/kg ICG intravenously to detect fluorescent lesions, thus guiding their excision.148–152,154,155 Only Filippello et al. evaluated peritoneal lesions ex vivo after excision (Table 3).153

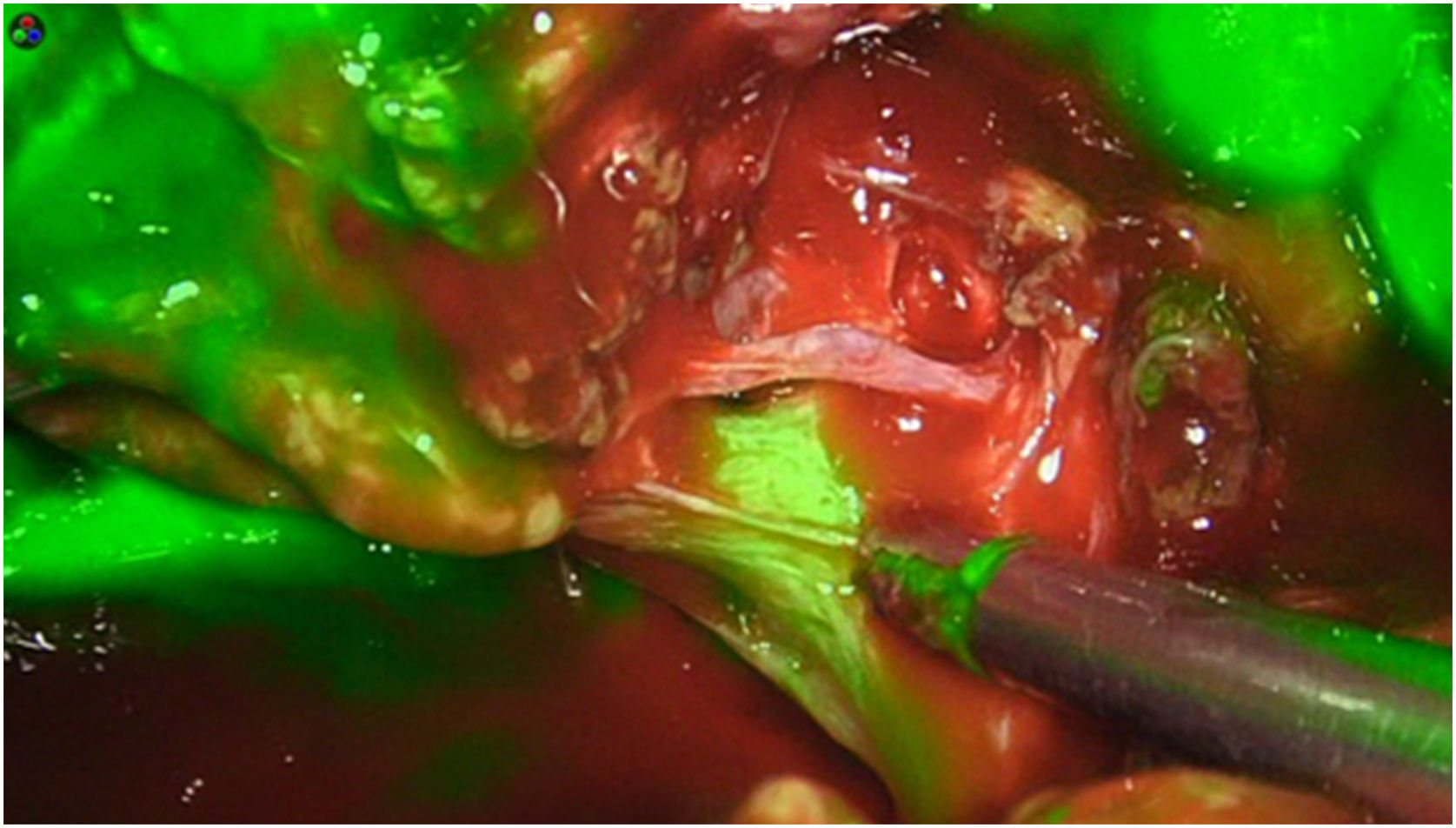

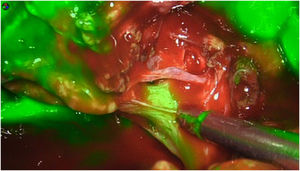

Retroperitoneal tumoursOur group has recently started using this technology to identify tumours at this level. We recently used it to remove a schwannoma located at the retroperitoneal level, and to assess its resection limits during dissection (Fig. 2). For this we gave an injection 30 min before surgery (in anaesthetic induction) as the tumour, being hypervascularised, would retain the ICG so it could be identified and correctly excised (Table 3).

Tissue perfusion to assess tissue infiltration - intestinal lymphomaFernández Veiga et al. presented their experience in a case of intestinal lymphoma.156 After administration of 15 mg of ICG intravenously before surgery, fluorescence allowed visualisation of a segment of small intestine and its lymph nodes, which were biopsied, revealing follicular lymphoma (Table 3).156

Diagnosis of lymphoma and other diseases by biopsy of difficult-to-access lymphadenopathiesLymphomas often need to be diagnosed by biopsy of lymphadenopathies located in places that are difficult to access, such as the retroperitoneum, neck, or mediastinum. These adenopathies present significant hypervascularisation, which has helped us to locate them due to the uptake of ICG when they have been injected beforehand during anaesthetic induction. Our group has had success in cases with adenopathies in the neck, thigh, and retroperitoneum.

We have used this same approach to detect suspected pathological lymphadenopathies in the retroperitoneum due to recurrence of germinal tumours, also with very satisfactory results (Table 3).

Use of indocyanine green in lymphadenectomy – sentinel lymph node and lymphatic mappingSentinel lymph nodeUsing ICG to identify the sentinel lymph node in oncological surgery is undergoing significant development with the idea of performing conservative surgery and avoiding extensive unnecessary lymphadenectomies, and is well developed in gastric,157–159 and breast cancer surgery.160–163

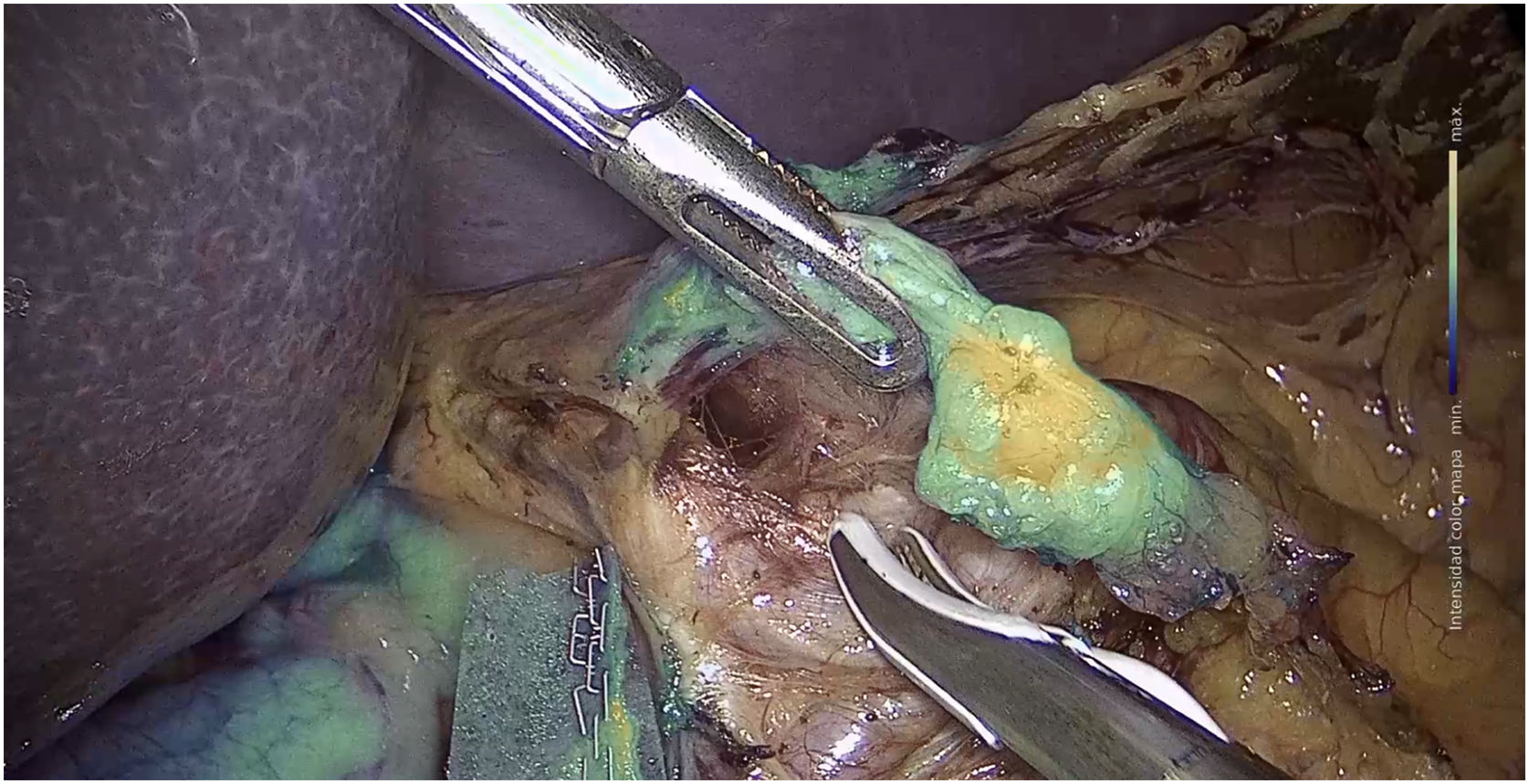

a) Stomach surgeryThe published studies on sentinel node identification by ICG fluorescence in gastric cancer, report identification rates of between 90% and 100% (Fig. 3).157–159 The SEntinel Node ORIented Tailored Approach (SENORITA) trial compares standard laparoscopic gastrectomy with laparoscopic sentinel node navigation surgery and endoscopic or segmental resection in T1N0M0.159 Using this technique, stomach-preserving surgery was performed in 81.4% of patients (Table 4).159

Sentinel lymph node and lymphatic mapping.

| Authors | N. of patients | Solution | Dose | Administration route | Administration time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach surgery – sentinel lymph node | |||||

| Bok et al.158 | 13 | n.s. | .5 ml (2.5 mg) | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoral quadrants during endoscopy | At the start of the intervention |

| An et al.159 | 245 | Technetium-99m-radiolabelled human serum albumin | 2.5 mg/ml | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoral quadrants during endoscopy | At the start of the intervention |

| Breast surgery – sentinel lymph node | |||||

| Wishart et al.160 | 100 | n.s. | 2 ml (.5%) | 1 ml intradermally1 ml subcutaneously at the edge of the areola | At the start of the intervention |

| Mieog et al.161 | 24 | Sterile water and human serum albumin | 1.6 ml(from 50 to 1000 μM) | A peritumoural or periareolar puncture | At the start of the intervention |

| Jung et al.162 | 24 | Distilled water and human serum albumin | .3 ml (.6 mg) | A peritumoural or periareolar puncture | At the start of the intervention |

| Takemoto et al.163 | 24 | Distilled water | 2 ml (10 mg) | A subareolar puncture | At the start of the intervention |

| Colorectal surgery – lymphatic mapping | |||||

| Currie et al.166 | 30 | n.s. | 5 mg/ml | In the submucosa at the 4 peritumoral quadrants during colonoscopy | At the start of the intervention |

| Handgraaf et al.167 | 5 | Nanocolloid | .4ml | In the submucosa at the 4 peritumoral quadrants during colonoscopy | At the start of the intervention |

| Nishigori et al.168 | 21 | n.s. | .2−.3 ml (2.5 mg/ml) | In the submucosa in 2 or 3 peritumoural punctures during colonoscopy | From 1 to 3 days before the intervention |

| Kazanowski et al.169 | 5 | Sterile water | 2−5 ml | In the submucosa around the tumour during colonoscopy | During surgery |

| Noura et al.170 | 25 | n.s. | 5 mg/ml | In the submucosa to the 4 peritumoural quadrants | At the start of the intervention |

| Zhou et al.16 | 12 | n.s. | .1 mg/ml | In the submucosa to the 4 peritumoural quadrants | At the start of the intervention |

| Watanabe et al.171 | 31 | Sterile water | 2.5 mg/ml | Punctures in the subserosa to the 4 peritumoural quadrants | At the start of the intervention |

| Chand et al.172 | 10 | n.s. | 1 ml (from .5 to 1.6 mg/ml) | Punctures in the subserosa to the 4 peritumoural quadrants | After vascular ligation and mobilisation of the colon |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice. Colon: | – | Sterile water | Two wheals at a concentration of 3 cm3 with 15 mg ICG | Punctures in the subserosa to the 2 peritumoural quadrants | At the start of the intervention |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice. Recto medio/alto: | – | Sterile water | Two wheals at a concentration of 3 cm3 with 15 mg ICG | Punctures in the subserosa to the 2 peritumoural quadrants | 12−24 h before the intervention |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice. Recto bajo: | – | Sterile water | Two wheals at a concentration of 3 cm3 with 15 mg ICG | Punctures in the subserosa to the 2 peritumoural quadrants | At the start of the intervention |

| Oesophageal surgery – lymphatic mapping | |||||

| Schlottmann et al.11 | 9 | Sterile water | .5cm3 (1.25 mg/ml) | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy | Before the laparoscopic part |

| Hachey et al.174 | 10 | Sterile water or serum albumin | 2.5 mg/ml | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy | At the start of the intervention |

| Yuasa et al.175 | 20 | n.s. | .5 ml | Two peritumoural punctures in the submucosa | After thoracotomy |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | 1.25 mg/ml | In the submucosa in the 4 quadrants, 5 cm3 peritumoural during endoscopy | 12−24 h before the intervention |

| Stomach surgery – lymphatic mapping | |||||

| Ohdaira et al.176 | 6 | n.s. | 1 ml (33 μg/ml) | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy | The day before the intervention |

| Miyashiro et al.177 | 10 | n.s. | .25−1.25 mg/.5 ml | 4−8 peritumoural punctures during endoscopy | At the start of the intervention |

| Lee et al.178 | 20 | n.s. | 1 ml | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy | At the start of the intervention |

| Shoji et al.179 | 20 | n.s. | .5 ml | To the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy | After section of the large omentum |

| Tajima et al.180 | 3125 | n.s. | .5 ml | - In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy- Punctures in the subserosa to the 4 peritumoural quadrants | - From 1 to 3 days before the intervention- At the start of the intervention |

| Kusano et al.181 | 22 | n.s. | .5 ml | Punctures in the subserosa to the 4 peritumoural quadrants | At the start of the intervention |

| Tummers et al.182 | 26 | Nanocolloid and saline solution | 1.6 ml (.05 mg) | Punctures in the subserosa to the 4 peritumoural quadrants | At the start of the intervention |

| Liu et al.183 | 61 | n.s. | .3125 mg/.5 mlper quadrant | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy | The day before the intervention |

| Chen et al.184 | 129 | Sterile water | .3125 mg/.5 mlper quadrant | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy | 20−30 h before the intervention |

| Baiocchi et al.185 | 13 | n.s. | 2.5 mg/ml by endoscopy (1−3 ml).25 mg/ml through the surgery (1−3 ml) | In the submucosa in the 4 peritumoural quadrants during endoscopy or subserosa during surgery | The day before the intervention or at the start of the intervention |

| Morales-Conde et al. in routine clinical practice | – | Sterile water | 1.25 mg/ml | In the submucosa in all 4 quadrants, .5 cm3 peritumoural by endoscopy | 12−24 h before the intervention |

| Melanoma surgery – lymphatic mapping | |||||

| Göppner et al.186 | 24 | Sterile water | .25 mg/ml | Subcutaneous punctures around the tumour | At the start of the intervention |

n.s., not specified.

ICG fluorescence imaging has demonstrated high sensitivity for sentinel node detection in breast cancer.160–163 A study in 100 clinically node-negative patients compared different techniques for sentinel lymph node detection.160 Sensitivity was 100% with ICG, the combination of ICG and methylene blue had a sensitivity of 95%, and was 72.2% with the combination of ICG and radioisotope.160 In this study, the dose administered just before surgery was 2 ml at .5% ICG (1 ml intradermally and 1 ml subcutaneously), and its effect was observed at 5−10 min.160 Combination therapy including ICG could be a feasible and safe method for sentinel node identification in these patients (Table 4).162,163

Lymphatic mappinga) Colorectal surgeryICG in the intraoperative detection of lymph nodes in colorectal cancer can be used for lymphatic mapping during lymphadenectomy (Table 4).16,164–172 This aspect is especially important if these nodes are not present in the usual dissection area, this information would change the surgical strategy.159,168

In colon surgery, peritumoural injection is performed intraoperatively by laparoscopy at subserosal level, but the objective is not achieved in all cases, either because the contents are spilled or because there is not enough time for it to diffuse adequately, and more reliable injection methods need to be established.16,166–172 Our group, in order to encourage lymphatic drainage once the ICG injection has been given (Fig. 4), begins dissection in the right colon via the cranial route, to preserve lymphatic drainage and allow time for ICG diffusion, observing its usefulness in complete excision of the mesocolon. In the splenic angle, the use of ICG can show the drainage of the tumour towards the territory of the inferior mesenteric artery or the middle colic artery.

Likewise, in rectal surgery, it can be injected just before starting the procedure by means of a rigid rectoscope or flexible rectoscopy 12−24 h before surgery, the best way of doing so needs to be defined. In rectal surgery, it could be of added value in assessing the need to remove the lateral lymph node chains.

b) Oesophageal surgeryOesophageal cancer spreads multidirectionally via submucosal lymphatics to regional lymphatic stations, lymphatic metastases are a major prognostic factor,11,173–175 and extensive lymphadenectomy is required to improve prognosis.11,173–175 ICG fluorescence imaging is being studied for lymphatic mapping for guided lymphadenectomy.11,173–175 Early studies have shown an increase in the number of lymphadenopathies when ICG is performed for lymphatic mapping.11,173–175 However, more studies are needed before introducing this procedure into daily conventional clinical practice, although it appears to be useful considering the current limitations (Table 4).11,173–175

c) Stomach surgeryMost studies only discuss ICG fluorescence-guided imaging for lymphatic mapping descriptively, as it does not really change the initially planned surgical strategy.176–185 However, all studies conclude that ICG fluorescence imaging provides high sensitivity and guided imaging for sentinel node identification and lymphatic mapping (Table 4).176–185

Baiocchi et al. showed that all lymph nodes that were metastatic had ICG uptake, with no metastatic lymph nodes without ICG uptake.185 Furthermore, this study showed that in some patients it was necessary to extend the lymphadenectomy outside the standard territory due to nodes with ICG uptake, noting that there was a positive lymph node in one case.185

These findings should of course be confirmed with further studies and in cases of neoadjuvant or advanced tumours.

d) Melanoma surgeryThe dose of ICG routinely used for lymphatic mapping for melanoma is 2 ml, at a concentration of 0.25 mg/ml.186 A few minutes after injection, the dose is increased until a maximum of 2 ml is reinjected, with a maximum total injected dose of 3.5 mg of ICG (or 5 ml) per patient.186 A node detection rate of 80% was achieved with pre-operative administration of 2 ml of ICG (2.5 mg/ml) (Table 4).186

ConclusionsICG fluorescence imaging is a very useful technology in general surgery. There is sufficient evidence to show that ICG is a safe, simple, and easy to manage resource, very useful in identifying anatomical structures, tissue vascularisation, tumours, and lymph nodes. The dosage and method of use varies from one group to another, and there remains little consensus in this regard, which is essentially based on whether fixed doses should be used or whether they should go by the patient's weight, which leads to dose adjustment without really influencing the results. Dilution with albumin seems to be indicated only for use in the sentinel node, whereas the conventional approach is to dilute with distilled water.

More prospective and randomised studies with large patient samples are needed to draw definitive conclusions on the use and method of use of fluorescence in general surgery, although the evidence gathered thus far is very encouraging.

Authors’ contributionsSalvador Morales-Conde: study designs, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of results, drafting the manuscript, critical revision, and approval of the definitive version of the manuscript.

Eugenio Licardie: study designs, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of results, drafting the manuscript, critical revision, and approval of the definitive version of the manuscript.

Isaias Alarcón: study designs, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of results, drafting the manuscript, critical revision, and approval of the definitive version of the manuscript.

Andrea Balla: study designs, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of results, drafting the manuscript, critical revision, and approval of the definitive version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestsSalvador Morales-Conde, Eugenio Licardie, Isaias Alarcón and Andrea Balla have no conflicts of interest or funding to declare.

Please cite this article as: Morales-Conde S, Licardie E, Alarcón I, Balla A. Guía de uso e indicaciones de la fluorescencia con verde de indocianina (ICG) en cirugía general: recomendaciones basadas en la revisión descriptiva de la literatura y el análisis de la experiencia. Cir Esp. 2022;100:534–554.