In surgery, the construction of knowledge is shaped in two scenarios: evidence-based medicine, and experiential learning. The former has become an essential pillar in this process. Based on this fact, clinical practice guidelines have been developed. However, their transient nature, constant renewal, and lack of individualization distance them from daily clinical activity. On the other hand, there is the construction of knowledge through vicarious and experiential learning. Its existence is linked to the beginning of medicine, and its importance is irrefutable. However, it is laden with the “truth effect”, surgical dogma and singularism. When integrating the construction of knowledge in these scenarios, critical thinking skills are paramount and necessary to guide the surgeon in the decision-making process within the context of surgical dynamism. This article explores this situation and its impact.

En cirugía la construcción de conocimiento está moldeada en dos escenarios, la medicina basada en la evidencia y el aprendizaje experiencial. La primera se ha constituido como un pilar esencial en este proceso. A partir de esta se han desarrollado las guías de práctica clínica. Sin embargo, su temporalidad, su constante renovación y la falta individualización, las distancian del actuar diario. Por otro lado, está la construcción de conocimiento mediante el aprendizaje vicario y experiencial. Su existencia va ligada al inicio de la medicina, y su importancia es irrefutable. No obstante, va cargado del “efecto verdad”, del dogma quirúrgico y del singularismo. El desarrollo de un sentido crítico frente a la integración de la constricción del conocimiento en estos escenarios, es primordial y necesario para guiar al cirujano en la toma de decisiones en el dinamismo quirúrgico. El presente artículo explora esta situación y su impacto.

“Veritas filia temporis” (La verdad es hija del tiempo) Francis Bacon

Surgical knowledge is based on a complex truth that still has gaps, which must be interpreted in the future surgeon's actions. This is illustrated by the example provided below.

A second-year general surgery resident performs a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, accompanied by the professor. In the context of acute cholecystitis with a difficulty level of 5/5 according to the Parkland classification1 (extreme degree of complexity with a high probability of complications), and after the gallbladder was removed, the professor asked, “Would you place a drain tube?” Before answering, the student recalls past surgeries, as well as data from the literature, and is not sure what to do. Finally, the resident evades the answer and replies, “Whatever you prefer, Doctor.” What was the correct answer? Was there a correct answer?

In medical training, knowledge is constructed in various ways. There is passive learning based on reading and on the individual exercise of analysis and integration of information. This is consolidated in evidence-based medicine (EBM), and in many instances it is supported by clinical practice guidelines (CPG). However, there is frequently a conflict between the evidence and learning that arises in a hospital environment derived from continuous practice.2 Experiential learning as a builder of knowledge is comprised of individual experience, peer or student-teacher tutoring, and observation and discussion among experts and colleagues (vicarious learning). Thus, knowledge is built through active listening and reflective thinking upon the experience of others.3

Today, medical science faces a reproducibility crisis. EBM is affected by time requirements, and CPG have an increasingly shorter half-life.4,5 The surgical learning environment is based on hierarchical training, which implies less questioning of the dogmas and firm opinions of academic superiors.6 Furthermore, surgeons generate a complex emotional relationship with their procedures and complications, and sometimes they reject learning despite the evidence supporting a change in behavior.4 In this way, a matrix of opinions arises about what is to be considered “true”. The objective of this document is to analyze the complexities involved in the construction of knowledge in surgery based on changing theoretical and experiential processes.

Clinical practice guidelines: construction of the truth?CPG are documents that have been developed systematically to help physicians make decisions with the aim to improve the quality of care by promoting interventions with proven and methodologically reliable benefits.7 CPG have emerged from EBM as a response to the variability observed in the treatment of medical problems, especially where there is a need for consensus in the face of a high degree of uncertainty.4

In surgery, CPG have limitations in the construction and application of knowledge. In the surgical environment, there are individual and dynamic conditions that are not based on plural, static theories.2 EBM is not absolute in the face of unpredictable or changing daily actions. It tends to be incomplete when the exceptions to the rule are numerous. This is observed in the low proportion of randomized clinical trials in the surgical field (<5%); thus, constructing a truth in this context requires a different approach.4

Consequently, surgeons have constructed their own experiential truth. Knowledge is acquired from the receptivity to learn from practice.2 The literature is questioned due to methodological flaws in study design and implementation.4 Therefore, the truth imposed by CPG in surgery is insufficient for practical application, and, although they attempt to find common ground and normalize behaviors, CPG ultimately encourage contradiction, and surgeons feel inspired to act based on their own experiential consensus. Whether or not to place a drain, operate on a comorbid patient, change the initial surgical plan, create an anastomosis or ostomy, etc, are daily decisions for surgeons. But, the question is, from what construct of knowledge are these definitions made? Does the literature (and, consequently, the CPG) agree with the experience of the surgeon?

Empirical evidence has shown that proper implementation of CPG improves patient outcomes. However, it has also explicitly demonstrated that decisions based solely on evidence are insufficient. These consider an “average patient”, and recommendations are not individualized. There are even inconsistencies in the final CPG recommendations based on the same literature.2,7 Therefore, the interpretation of the quality of the evidence becomes mandatory and determines the confidence in the effect and the adequate support to make decisions.7 It increases their ability to be part of accurate knowledge, which implies a balance between risks, commitment of values, resources, feasibility of application, accessibility and equity. The level of evidence reached, the validation, and the revalidation resulting from confronting the new knowledge make CPG useful tools for making surgical decisions. The inclusion of multidisciplinary groups helps reduce cognitive bias and subjective individual shaping resulting from a personal perspective.4 Therefore, EBM and CPG must be associated with specific training about how they should be understood, interpreted, implemented and reproduced, while also addressing their limitations and the future challenges they pose.2,7

The truth effect and experiential learningLearning in surgery is part of a collective construction of knowledge. Medical uncertainty emerges when theoretical knowledge is applied to clinical practice in the context of physiological and psychological aspects of patient care.2 Is knowledge safe when based on oral tradition yet not verified with the scientific method? The “truth effect” must be analyzed in order to answer this question. It is unknown how the brain decides whether information received is reliable or not, or how the falsities are differentiated from the truth. People are predisposed to judge repetitive statements as true due to more fluid processing of reiterated information versus new knowledge. It is perceived as more familiar and, therefore, more trustworthy.8 Each person analyzes the facts based on coherent references in their memory and, if established connections are found, then the ideas are easier to process and to consider true.9,10 However, judging what is actually true or not becomes a bigger challenge. For example, how many times have we repeated phrases learned from teachers, without verifying their authenticity?4 This is especially important in a field where experiential learning and oral tradition have so much power. To a certain extent, surgeons are at the mercy of the surgical dogma of their instructors.6

For instance, the literature has shown that the use of drain tubes in complicated laparoscopic appendectomies does not reduce the formation of collections in the postoperative period, although it does prolong hospital stay.11 However, a resident who repeatedly sees and hears why drain placement is better may solidly accept this idea, even though EBM may prove otherwise. The critical development of surgical judgment becomes important in the construction of knowledge and in the search for that “truth”: neither literature nor experiential learning are absolute.

To understand surgical judgment within the truth effect, one must consider that emotions affect the integration of knowledge.12 Fluidity implies that there is little effort to process a stimulus8,10; if a surgeon creates an emotional attachment to a postoperative complication (such as the benefits or disadvantages associated with drain tube placement), the decision-making process may be affected. This becomes a risk factor if the student or resident does not corroborate what is transmitted by their teachers with the empirical evidence. Thus, statements like, “I always place a drain tube and it has worked for me”, become an absolute.

Training surgeons on the way in which experience-based knowledge is constructed may make them more critical of this process and thereby reduce the impact of the truth effect.10 Robust, quality argumentation with critically analyzed evidence leads to high-quality clinical reasoning.10 By generating an idea based on vicarious learning and a related question learned from CPG, or vice-versa, it is easier to build a bridge between evidence-based medicine and experience-based medicine. This provides for a balanced construction of knowledge.10

Finally, we should note the role of post-truth, which is the questioning of and skepticism about dogmatic truth, which separates the understanding of the issues into “what things are” and “what we believe about them”.12 Its presence in medicine—including the surgical field—arises from the overabundance of information and the interests of the different participants in the healthcare process. It entails critical questioning that sets the rigidity of CPG against the laxity of experiential learning. It is challenging to dose post-truth in a structured manner, as it should be addressed during medical training, continue during future professional practice, and also be regulated in favor of good clinical practice.

Integrating evidence-based medicine and experienceSurgical decision making is no trifling matter. In surgery, the instinctive ability to know when to operate or when not to operate becomes enhanced. An example of this is intraoperative decision-making with changing surgical plans, in variable anatomical exposures, or in a dynamic environment (patient, clinical scenario, interactions, etc.). Neither knowledge nor judgment are easy to teach or assess, as they arise from experiential learning based on periods of observation and immersive participation in tasks and rituals in conjunction with what is learned through EBM.4 In this situation, the scientific method and technological tools like artificial intelligence offer theoretical and practical support.

The scientific method is the process by which beliefs are evaluated and tested.13 For it to be optimized, technological and artificial intelligence (AI) prediction algorithms have emerged.14 In surgery, the routine use of AI has been regularized unconsciously.12 This has been received by educators with enthusiasm and skepticism. However, there is still resistance to its use.14,15

AI provides tools that facilitate the balance between evidence-based medicine and experience-based medicine. Computer learning and vision are responsible for processing and analyzing digital images in order to predict decision making and make more reliable predictions. An example is the development of models to predict surgical risk and decision-making in skin cancer and analysis of colonoscopies.16,17 Thus, significant progress has been favored in the medical-surgical field.14

New technologies, such as robotic surgery, tele-surgery, instruments and programs under development, offer an attractive alternative and, in turn, require caution in terms of their role in the construction of knowledge. Knowledge can be seen like a factory production line, with new ideas entering on a conveyor belt and passing through a series of filters. Some ideas will fall off the conveyor, while others will be rejected due to imperfections or even due to design flaws. At the end, the final products are “boxes of knowledge”, which will then undergo testing by humans (experience) and by machines (EBM, AI) before being marketed. Constant evaluation along the production, distribution or consumption lines results in modifications to improve the final product: surgical knowledge.

The question is then raised: is it possible to put into practice all the ideas that come along on the conveyor belt? Their potential scope creates a sense of hope for the future; such is the case of robotic surgery. However, innovations with limited evidence should be limited to very low-risk interventions, controlled by studies to complement other knowledge, and always with the approval and understanding of the patient. New technologies must go a long way before their implementation and recognition as a new surgical paradigm.

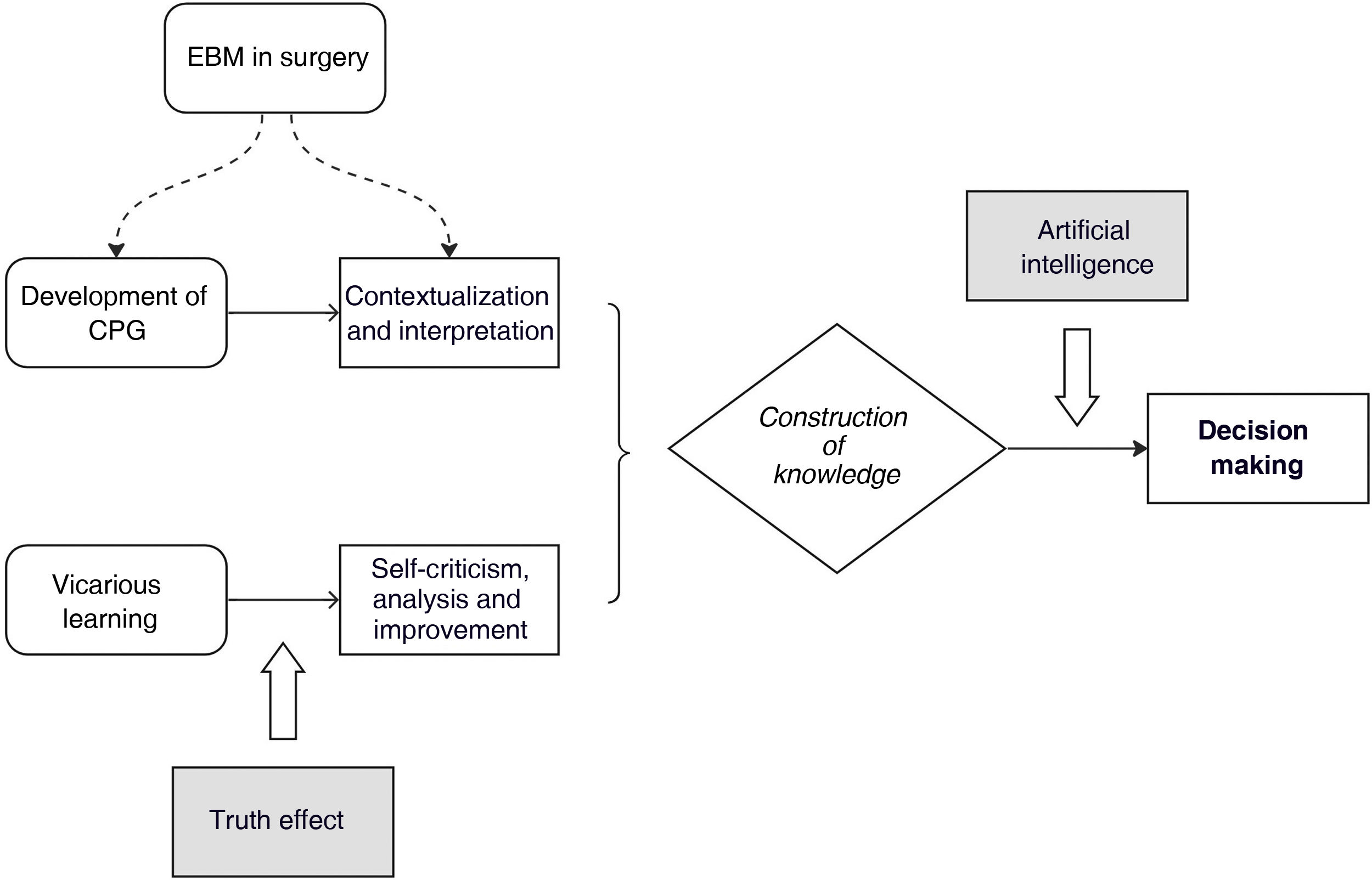

How does all this apply to the initial case? The ultimate goal is not to determine whether or not the resident should place a drain tube. Only time will tell, because the current truth (if there is one) is changing, temporary and relative, both literally and experientially. There is no absolute truth or a single “right” answer. What this text intends is to give its reader tools to think critically in order to promote balanced decision-making between EBM and experience-based medicine. Strategically implementing technological advances to improve (not impede) experiential learning results in an appropriate approach to construct knowledge.15 It is necessary to recognize the resources available to transcend the industry-wide recommendations of CPG as well as the singularity of personal experience. This theoretical approach is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Final thoughtsWhat would be the impact of software designed to warn us about an unsafe cholecystectomy, or about the appropriateness of drain tube positioning, to guide surgeons in making intraoperative decisions? It would be possible to bring EBM concepts to a digital format in which the current literature interacts in real time during a surgical procedure. In this manner, an integrating strategy is generated between observation and action for real-time decision making. This could lead to safer and more intelligent procedures. Raising awareness about the process would achieve a balance between EBM and vicarious learning as part of ever-changing surgical training.

The construction of surgical knowledge is shaped by an empirical process, with temporary truths directed by EBM and CPG, which must be constantly questioned. EBM in surgery lacks strength as the only learning base. The truth effect exposes the limitations of experiential learning as the only source of knowledge. A race towards the future is proposed with the use of digital technologies that support the recognition of human variability in order to generate awareness, without replacing or dismissing experiential or emotional learning.

There is no one true explanatory theory, nor is there just one sensible hypothesis. The construction of the truth is a process of constant self-criticism used to regulate a matrix of opinions.13 With the use of artificial intelligence, the theoretical basis is accessible during experiential learning. This allows for surgeons to be trained in limits, since surgical knowledge exists at the interface between biological anatomy and technology, while also allowing for constant renewal of the lines between medical practice and evidence, and between art and science.2

Conflict of interestsNone.

Please cite this article as: Quintana Montejo N, Vega Peña NV, Domínguez Torres LC. La construcción del conocimiento en cirugía: un proceso artesanal. Cir Esp. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2023.02.021