The standard treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) and mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CC) is surgical resection, nevertheless, recent studies show adequate survival rates in selected patients with iCCA or HCC-CC undergoing liver transplantation (LT).

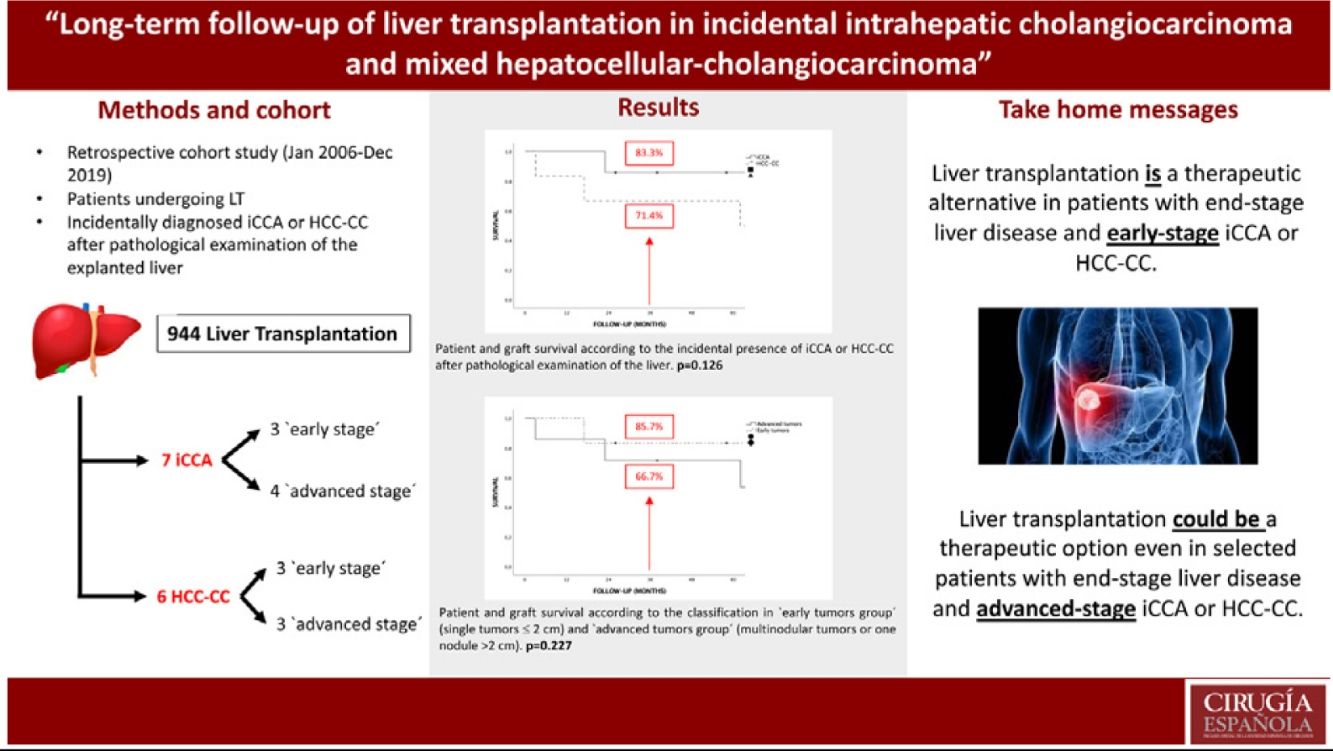

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was design including all patients undergoing LT at our center between January, 2006 and December, 2019 with incidentally diagnosed iCCA or HCC-CC after pathological examination of the explanted liver (n = 13).

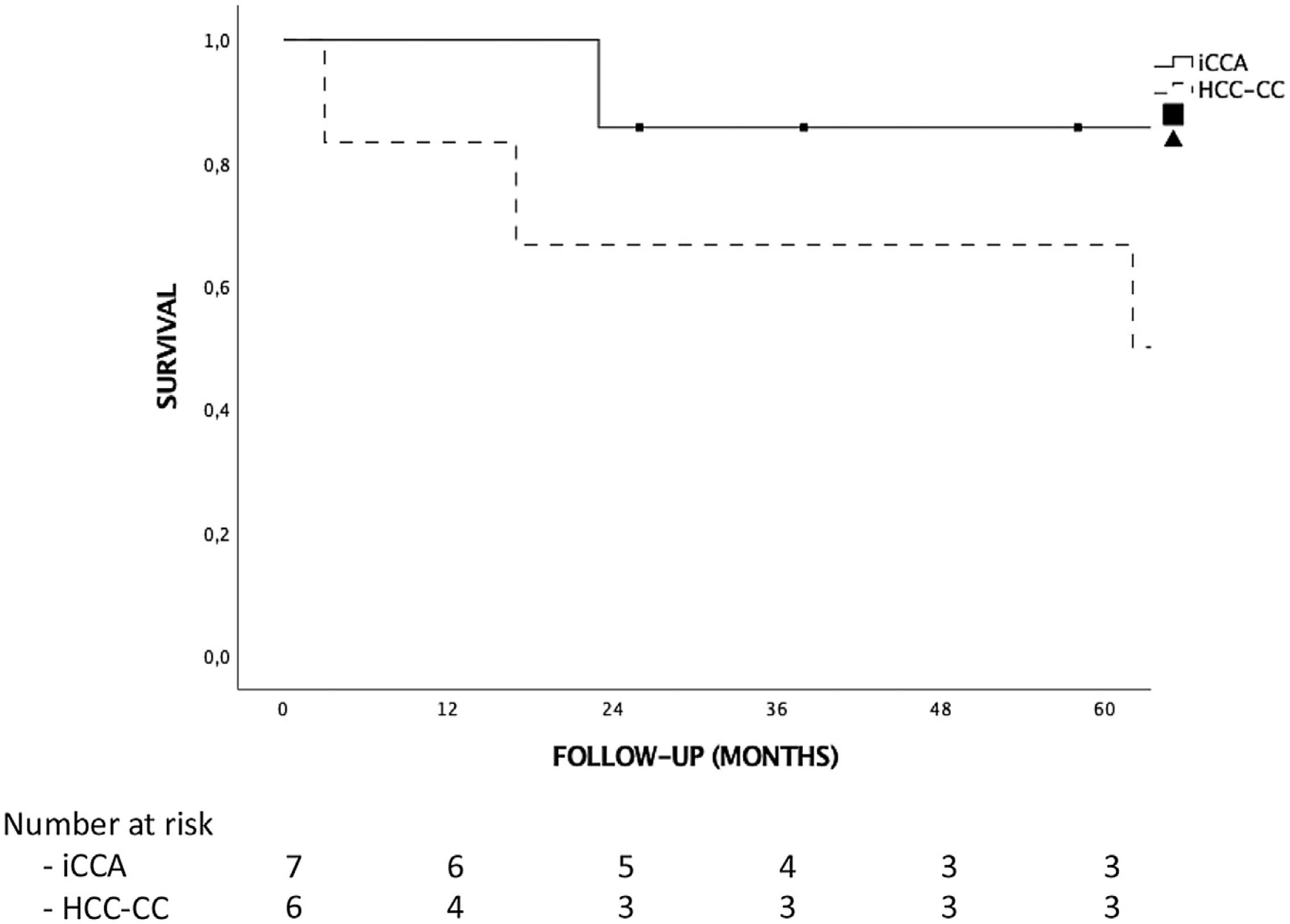

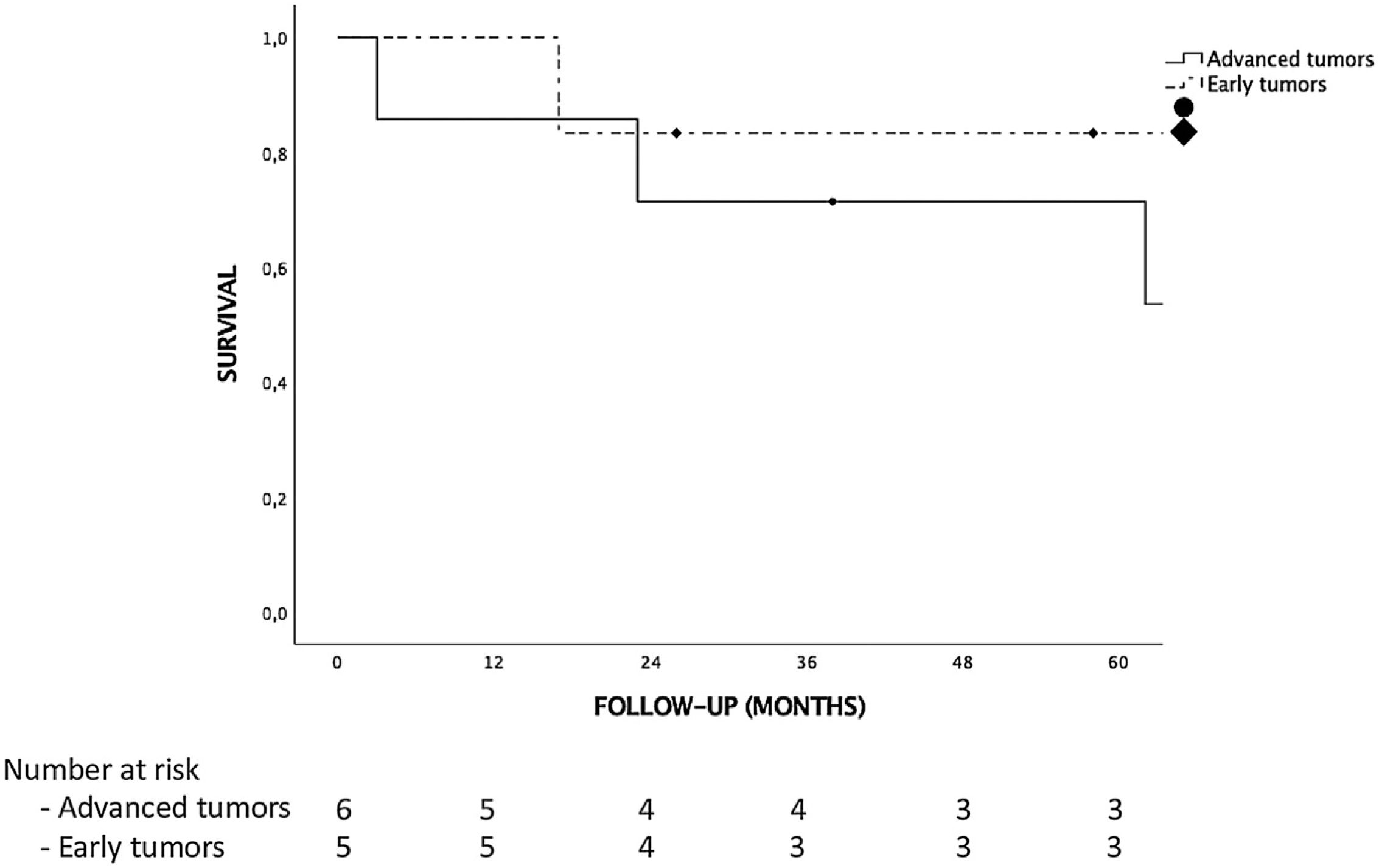

ResultsThere were no iCCA or HCC-CC recurrences during the follow-up, and hence, there were no tumor related deaths. Global and disease-free survival were the same. The 1, 3 and 5-years patient survival were 92.3%, 76.9% and 76.9%, respectively. Survival rates in the “early-stage tumor group” at 1, 3 and 5 years were 100%, 83.3% and 83.3%, respectively, with no significant differences as compared to the “advanced-stage tumors group”. No statistically significant differences in terms of 5-year survival were found when comparing tumor histology (85.7% for iCCA and 66.7% for HCC-CC).

ConclusionsThese results suggest that LT could be an option in patients with chronic liver disease who develop an iCCA or HCC-CC, even in highly selected advanced tumors, but we must be cautious when analyzing these results because of the small sample size of the series and its retrospective nature.

El tratamiento de elección del colangiocarcinoma intrahepático (iCCA) y el hepato-colangiocarcinoma mixto (HCC-CC) es la resección quirúrgica, sin embargo, estudios recientes han demostrado buenos resultados en pacientes seleccionados sometidos a un trasplante hepático (TH).

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de una cohorte formada por todos los pacientes que recibieron un TH en nuestro centro entre Enero 2006 y Diciembre 2019 con hallazgo incidental de un iCCA o un HCC-CC durante el estudio histopatológico después del trasplante (n = 13).

ResultadosDespués de una mediana de seguimiento de 65 meses no hubo ninguna recurrencia tumoral, por lo que la supervivencia global y libre de enfermedad fueron iguales. La supervivencia a 1, 3 y 5 años de la muestra fue del 92.3%, 76.9% y 76.9%, respectivamente. La supervivencia de los pacientes con un ‘early stage’ a 1, 3 y 5 años fue del 100%, 83.3% y 83.3%, respectivamente; sin encontrar diferencias estadísticamente significativas al compararla con la de los pacientes con un ‘advanced stage’. Aunque la supervivencia de los pacientes con iCCA fue mayor que la de los pacientes con HCC-CC (85.7% vs. 66.7% a 5 años, respectivamente), las diferencias no fueron estadísticamente significativas.

ConclusionesEl TH podría ser una opción de tratamiento en pacientes con enfermedad hepática terminal que desarrollan un iCCA o un HCC-CC, incluso en estadios avanzados seleccionados, pero estos resultados deben ser analizado con precaución dada la naturaleza retrospectiva del estudio y el escaso tamaño muestral.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) is the most common primary tumor of the liver after hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The incidence of iCCA has increased in western countries during the recent years, with a higher number of cases in cirrhotic livers.1–5 Currently, the only curative treatment for iCCA is surgical resection but, the outcomes after liver resection are poor with high recurrence rates and low 5-year survival ranging between 25%–40%.6

Mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CC) is a less frequent liver tumor but it is still the most frequent mixed tumor of the liver. Its incidence varies between 1%–14% according to different studies and an improvement in pathology analysis techniques has led to an increase in its diagnosis.7–9 In 1949, the Allen-Lisa classification10 divided mixed liver tumors in three types. Afterwards, in 1985 Goodman et al.11 simplified this classification into two tumor types: type I, both HCC and iCCA in different nodules within the same liver; and type II, intermediate differentiation between HCC and iCCA in the same nodule corresponding to a mixed HCC-CC. The available studies show a poor outcome for these tumors, as compared with iCCA, with a 3-year survival only 10%–40% after liver resection.

Although the incidence of iCCA and HCC-CC are globally low, they can be found occasionally on the final pathological examination of the explanted liver after LT. In most cases, the incidental diagnosis of iCCA and HCC-CC is made in patients undergoing LT for HCC over a cirrhotic liver. Over the years, iCCA has been an accepted contraindication for LT in most transplants centers because of its dismal prognosis with 5-year survival rates below 50% after LT.12–18 Nevertheless, recent studies show adequate survival rates in selected patients with iCCA or HCC-CC undergoing LT, similar to those patients with HCC.19,20

There is currently no consensus about indication of LT in patients with HCC-CC because of the low number of reported cases, but the last studies suggest that LT could be a reasonable treatment option for highly selected patients with iCCA in early stages.

The aim of this study is to analyze the outcomes of LT in patients with incidental pathological diagnosis of iCCA or HCC-CC at our center.

MethodsStudy designA retrospective cohort study was designed, including all patients undergoing LT at our center between January, 2006, and December, 2019 with incidental diagnosis of iCCA or HCC-CC after pathological examination of the liver. The indication for LT in all patients was end-stage liver disease or suspected HCC. Patients without known nodules before LT were not excluded for the analysis as it could enlarge the series and provide more information about oncological outcomes. All patients with HCC were within Milan criteria21 at the moment of LT. Follow-up was completed December 2021. During the analysis the sample was divided into two groups based on explant pathology, as the “iCCA group” (patients with iCCA or with HCC-CC Goodman type I) and the “HCC-CC group” (patients with HCC-CC Goodman type II) as previously reported.19 Furthermore, each group was divided into subgroups by stage, which were identified as an “early tumor group” (defined as a single tumor ≤ 2 cm) and an “advanced tumor group” (defined as multinodular tumors or one nodule >2 cm), according to the classification proposed by Sapisochin et al.20

HCC screeningScreening for HCC was carried out in cirrhotic patients every 6 months. When a nodule ≥1 cm was found on a multiphasic contrast-enhanced CT, a multiphasic contrast-enhanced MRI was performed. According to the HCC practice guidelines, the diagnosis was established in nodules ≥ 1 cm with hypervascularity in the arterial phase and washout on either portal venous and/or delayed phases. A CT or MRI was repeated in cases that did not meet the imaging criteria, and a biopsy was ordered only when a diagnosis was not achieved after a repeat imaging modality.22

Ablative therapiesAblative therapies were evaluated for all patients with HCC during their time on the waitlist to avoid tumoral progression in cases of suspected HCC, and either radiofrequency ablation (RFA), percutaneous ethanol injection, microwave ablation, trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) or radio-embolization were considered, according to the number, size and location of the tumors. Patients were removed from the waitlist if they showed tumoral progression beyond Milan criteria despite best locoregional treatment.

Recipient characteristicsAll recipients were evaluated in the out-patient clinic and inclusion on the transplant waitlist was made according to the department’s criteria and protocol, which is in line with Spain’s National Transplant Organization (ONT). The following patient variables were collected: age, sex, cause of cirrhosis, Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, type of liver donor, laboratory parameters including AFP levels, pre- and post- LT HCC diagnosis and locoregional treatments prior to LT. Pre-LT Ca 19-9 levels were not available since the pathological diagnosis was not suspected. All patients with HCC received 18 points once on the waiting list and 1 extra point every month until transplantation.

LT techniqueIn all patients hepatectomy was carried out with a vena cava-sparing technique (piggy-back). Portal anastomosis and portal reperfusion was performed firstly, followed by arterial anastomosis and arterial reperfusion. Biliary reconstruction was made without T-tube in most cases, with T-tube in cases of choledochal size disparity and with hepaticojejunostomy in cases of biliary disease. Lymphadenectomy was not performed in any case. All patients were provided with Tacrolimus, Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) and steroids as usual in our patients during the last years. After the first post-LT month, a “minimizing tacrolimus” strategy was used switching from MMF to Everolimus when possible. This strategy is used in all recipients with tumoral indications or patients who develop post-LT renal dysfunction. MMF or Everolimus monotherapy is performed on long-term follow-up in recipients who undergo LT for HCC or other tumors and in patients with severe adverse tacrolimus effects but stable liver function.

Post-LT surveillanceDuring the follow-up, a CT-scan was performed every 3 months until 6 months, every 6 months until 3th year an annually until 5th year. AFP and Ca 19-9 were analyzed too. The variables analyzed were iCCA or HCC-CC recurrence, time of tumor recurrence, mortality and cause of death. Post-LT complications were also recorded. The follow-up was censored at time of death or end of the study. In the event of death, the graft was considered a non-functioning graft.

Histopathologic examinationThe histological characteristics analyzed were the number and size of the lesions, the grade of differentiation according to the Edmondson-Steiner23 grade (well, moderate or poor differentiation), presence of vascular or neural invasion, satellitosis, lymph node involvement and tumor stage according to TNM system.24 We also analyzed compliance of Milan criteria21 and up to seven criteria25 in cases with HCC diagnosis in pathological examination.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range. Absolute frequencies (n) and relative frequencies (%) described categorical variables. Chi-square, t-student or U Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Analysis of survival and disease-free survival were performed with the Kaplan Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics, version 25 (SPSS, INC., Chicago, IL).

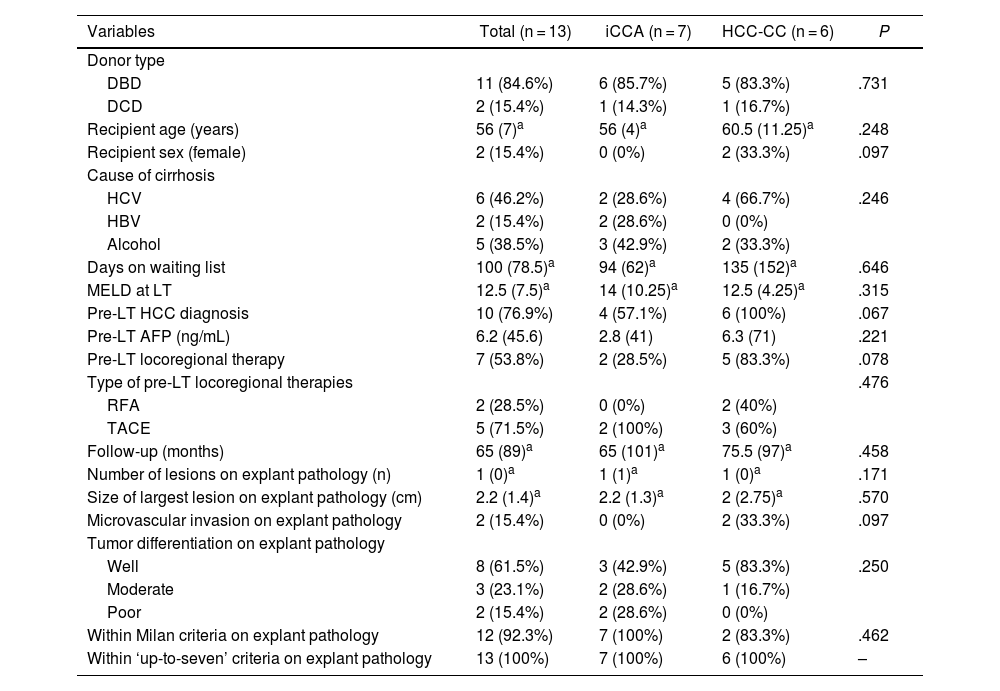

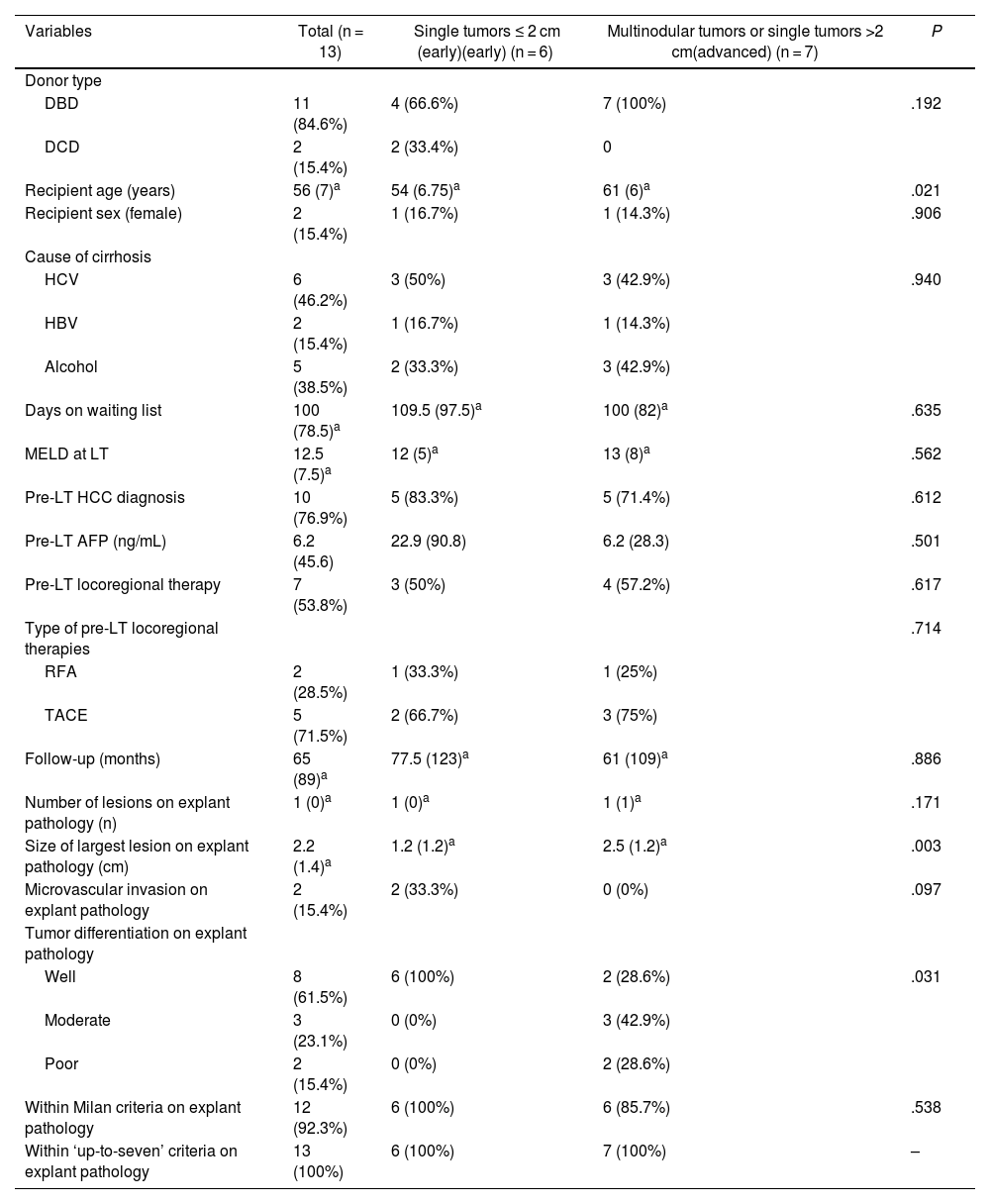

ResultsPatient characteristicsDuring the study period 944 LT were performed. Between them 13 (1,37%) patients with incidental diagnosis of iCCA or HCC-CC in the explanted liver were identified. Of them, 7 patients had diagnosis of iCCA (5 HCC-CC Goodman type I and 2 iCCA) (54%) and 6 HCC-CC (46%). LT was performed in 11 cases (84.6%) with donation after brain death (DBD) and in 2 cases (15.4%) with donation after cardiac death (DCD). The distribution regarding gender was 11 men (84.6%) and 2 women (15.4%) with a median age of 56 years. The most frequent cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis C virus (HCV) in 46.2% of patients followed by alcohol in 38.5% and hepatitis B virus (HBV) in 15.3%. No cases of primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary biliary cirrhosis were found. The median MELD score at the time of LT was 12. Median time on waiting list was 100 days. No significant differences were found in patient characteristics after comparing the “iCCA group” and “HCC-CC group” (Table 1), but recipients were significantly older in the “advanced tumors group” (61 years vs. 54 years; P = .021) (Table 2).

Patient demographics and tumor pathological characteristics, for the iCCA vs HCC-CC groups.

| Variables | Total (n = 13) | iCCA (n = 7) | HCC-CC (n = 6) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type | ||||

| DBD | 11 (84.6%) | 6 (85.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | .731 |

| DCD | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Recipient age (years) | 56 (7)a | 56 (4)a | 60.5 (11.25)a | .248 |

| Recipient sex (female) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) | .097 |

| Cause of cirrhosis | ||||

| HCV | 6 (46.2%) | 2 (28.6%) | 4 (66.7%) | .246 |

| HBV | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Alcohol | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (42.9%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| Days on waiting list | 100 (78.5)a | 94 (62)a | 135 (152)a | .646 |

| MELD at LT | 12.5 (7.5)a | 14 (10.25)a | 12.5 (4.25)a | .315 |

| Pre-LT HCC diagnosis | 10 (76.9%) | 4 (57.1%) | 6 (100%) | .067 |

| Pre-LT AFP (ng/mL) | 6.2 (45.6) | 2.8 (41) | 6.3 (71) | .221 |

| Pre-LT locoregional therapy | 7 (53.8%) | 2 (28.5%) | 5 (83.3%) | .078 |

| Type of pre-LT locoregional therapies | .476 | |||

| RFA | 2 (28.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40%) | |

| TACE | 5 (71.5%) | 2 (100%) | 3 (60%) | |

| Follow-up (months) | 65 (89)a | 65 (101)a | 75.5 (97)a | .458 |

| Number of lesions on explant pathology (n) | 1 (0)a | 1 (1)a | 1 (0)a | .171 |

| Size of largest lesion on explant pathology (cm) | 2.2 (1.4)a | 2.2 (1.3)a | 2 (2.75)a | .570 |

| Microvascular invasion on explant pathology | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) | .097 |

| Tumor differentiation on explant pathology | ||||

| Well | 8 (61.5%) | 3 (42.9%) | 5 (83.3%) | .250 |

| Moderate | 3 (23.1%) | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Poor | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Within Milan criteria on explant pathology | 12 (92.3%) | 7 (100%) | 2 (83.3%) | .462 |

| Within ‘up-to-seven’ criteria on explant pathology | 13 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 6 (100%) | – |

iCCA, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; HCC-CC, mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; LT, liver transplantation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; Cm, centimeters; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Patient demographics and tumor pathological characteristics, comparing Early vs Advanced groups.

| Variables | Total (n = 13) | Single tumors ≤ 2 cm (early)(early) (n = 6) | Multinodular tumors or single tumors >2 cm(advanced) (n = 7) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type | ||||

| DBD | 11 (84.6%) | 4 (66.6%) | 7 (100%) | .192 |

| DCD | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (33.4%) | 0 | |

| Recipient age (years) | 56 (7)a | 54 (6.75)a | 61 (6)a | .021 |

| Recipient sex (female) | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | .906 |

| Cause of cirrhosis | ||||

| HCV | 6 (46.2%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (42.9%) | .940 |

| HBV | 2 (15.4%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (14.3%) | |

| Alcohol | 5 (38.5%) | 2 (33.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | |

| Days on waiting list | 100 (78.5)a | 109.5 (97.5)a | 100 (82)a | .635 |

| MELD at LT | 12.5 (7.5)a | 12 (5)a | 13 (8)a | .562 |

| Pre-LT HCC diagnosis | 10 (76.9%) | 5 (83.3%) | 5 (71.4%) | .612 |

| Pre-LT AFP (ng/mL) | 6.2 (45.6) | 22.9 (90.8) | 6.2 (28.3) | .501 |

| Pre-LT locoregional therapy | 7 (53.8%) | 3 (50%) | 4 (57.2%) | .617 |

| Type of pre-LT locoregional therapies | .714 | |||

| RFA | 2 (28.5%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (25%) | |

| TACE | 5 (71.5%) | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (75%) | |

| Follow-up (months) | 65 (89)a | 77.5 (123)a | 61 (109)a | .886 |

| Number of lesions on explant pathology (n) | 1 (0)a | 1 (0)a | 1 (1)a | .171 |

| Size of largest lesion on explant pathology (cm) | 2.2 (1.4)a | 1.2 (1.2)a | 2.5 (1.2)a | .003 |

| Microvascular invasion on explant pathology | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | .097 |

| Tumor differentiation on explant pathology | ||||

| Well | 8 (61.5%) | 6 (100%) | 2 (28.6%) | .031 |

| Moderate | 3 (23.1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (42.9%) | |

| Poor | 2 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.6%) | |

| Within Milan criteria on explant pathology | 12 (92.3%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (85.7%) | .538 |

| Within ‘up-to-seven’ criteria on explant pathology | 13 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 7 (100%) | – |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; LT, liver transplantation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; Cm, centimeters; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

In 10 patients (76.9%), HCC was diagnosed previous to LT. Out of those patients, 7 (70%) were treated with locoregional therapies while they were waiting for LT. Five cases (71.4%) were treated with trans-arterial chemoembolization and 2 (28.6%) with radiofrequency ablation. In one case, surgical HCC resection was carried out prior to LT. Although pre-LT HCC diagnosis was more frequent in the “HCC-CC group”, as compared to the “iCCA group” (100% vs. 57.1%), differences were not statistically significant (Table 1), and no differences were found between “early tumors group” and “advanced tumors group” regarding pre-LT diagnosis of HCC. Seven patients with suspected HCC were treated with locoregional therapies prior to LT. Five patients were treated with TACE and 2 patients with RFA. In 4 cases we found partial radiological response and in 3 cases no response, but we only identified pathological response in 1 case with a 30% of tumoral necrosis in an HCC-CC. This case was a patient with an early HCC-CC who is alive 102 months after LT.

Histopathologic examinationPathological analysis showed incidental iCCA in 7 patients (53.8%) and HCC-CC in other 6 patients (46.2%). Six patients (46.2%) had a single nodule ≤ 2 cm and 7 patients (53.8%) had multinodular tumor or a single nodule >2 cm. Between these 7 patients, 2 had multinodular tumor consisting of 1 patient with a 1.6 cm iCCA and a 2.2 cm HCC-CC and another patient with 2 iCCA of 2.5 and 0.9 cm, respectively. Patients with a nodule >2 cm had nodules of 5 cm, 3.5 cm, 2.7 cm, 2.5 cm and 2.2 cm in each case. Only in 2 cases (15.4%) microvascular invasion was observed. Macrovascular invasion, peri-neural invasion, satellitosis or lymph node involvement were not found. Two of the tumors (15.4%) presented poor differentiation, 3 (23.1%) moderate differentiation and 8 (61.5%) were well differentiated, with a higher prevalence of well differentiated tumors in the “early tumors” group (100% vs. 28.6%, P = .031). The size of largest lesion was larger in the “advanced tumors group” as expected (2.5 cm vs. 1.2 cm; P = .003) (Table 2).

Tumor recurrence and survivalNo patient received adjuvant therapy after LT. Median follow-up after LT was 65 months. There were no differences in follow-up between the iCCA or HCC-CC group or early vs advanced tumor groups. There were no iCCA or HCC-CC recurrences during follow-up, hence, there were no tumor related deaths in our sample, and global and disease-free survival were the same. Only 3 (23%) patients had post-LT complications, 2 hemoperitoneum requiring reoperation and 1 patient Klebsiella pneumoniae who developed multiorgan failure and finally died. There were no liver re-transplantations, so patient and graft survival were the same too. The 1, 3 and 5-year survival for the complete sample were 92.3%, 76.9% and 76.9%, respectively. Five patients (38.5%) died during follow-up. Causes of death were cardiovascular in 3 patients, infection in 1 patient and lung cancer in 1 patient. Although survival analysis showed differences between the “iCCA group” and the “HCC-CC group” at 1, 3 and 5-year, they were not statistically significant and there were not tumor related deaths. Survival at 1, 3 and 5-year were 100%, 85.7% and 85.7% in the “iCAA group” compared to 83.3%, 66.7% and 66.7% in the “HCC-CC group” (Fig. 1). In the same way, there were also no statistically significant differences comparing the early vs advanced groups, with 1, 3 and 5-years survival of 100%, 83.3% and 83.3%, and 85.7%, 71.4% and 71.4%, respectively (Fig. 2).

The aim of the present work was to analyze the outcomes of LT in patients with incidental finding of iCCA or HCC-CC after pathological examination in a single-center series. Thirteen patients met this criterion, which represent 0.6% of all the LT performed at our hospital. This incidence is lower than that described in previous studies.19,20,26 In our sample, 2 patients (15.4%) were diagnosed with iCCA, 5 patients (38.5%) with HCC-CC Goodman type I and other 6 (46.1%) with HCC-CC Goodman type II. The median patient follow-up after LT was 65 months, which makes our paper the single-center study with the longest follow-up in recent publications.19,20,26

During the analysis patients were divided into two groups according to tumor size and number of lesions, in a manner according to that described by Sapisochin et al.19,20 in his previous two multicentric studies. In our series, 6 patients (46.2%) had single tumors ≤ 2 cm (‘early tumors’) with no disease recurrence during follow-up. This group showed a 5-years survival of 83.3%, which is higher than that obtained in previous studies.15,19,20,26 On the other hand, the advanced tumor group included 7 patients (53.8%) with larger tumors and poorer differentiation compared with the early tumor group. Nevertheless, there were no tumor recurrences during follow-up, and 5-years survival was not significant different as compared to the early tumor group.

These results suggest, as previous studies,19,20 that LT could be an option for highly selected patients with early stages of iCCA and HCC-CC. The results of this study, however, may suggest that in highly selected advanced tumors, LT could also be an alternative, considering the absence of tumoral recurrence and near equivalent survival to early-stage tumors. The criteria to determine which of these patients could benefit from LT are not known yet. Several multicenter international studies have suggested that tumor size correlates with recurrence and survival after LT, as in an international retrospective analysis20 where 5-years survival for tumors ≤ 2 cm was 65% compared with 45% in tumors > 2 cm. Nevertheless, a retrospective analysis to identify risk factors of iCCA recurrence after LT suggested that aggressive tumoral behaviour and absence of neoadjuvant therapy were stronger multivariate predictors of tumoral recurrence than tumor size.27 In other prospective study, where patients with locally advanced iCCA (tumor diameter ≥5 cm) were treated with neoadjuvant therapy and LT, 5-year survival was 83.3% with a recurrence rate of 50%, suggesting that chemo-response would serve as a better surrogate marker of tumor behaviour than size.28 In our study, no evidence of tumor recurrence in the advanced tumor group was found during follow-up and thus no tumor-related deaths. In this group, two patients had tumors between 2–2.5 cm, three between 2.5–3 cm, and two had masses larger than 3 cm, with no disease recurrence in any case. In our series, no differences between pre-LT locoregional therapies were found, and only in one case pathological response in an HCC-CC with a 30% of necrosis was identified, but the use of locoregional therapies as neoadjuvant treatments could play a role in the management of these patients as was seen in previous studies, allowing the evaluation of the tumoral behaviour according to the response. Future advances in genetic profiling might increase knowledge of these tumors and identify patients with targetable mutations and favorable biological behaviour for transplant, and those with high risk of recurrence in which transplant may not be an option.

The outcomes of our study are in accordance with those found in previous studies and reinforce the feasibility of LT for selected patients with iCCA or HCC-CC even in the advanced tumors. Nevertheless, these results should be carefully analyzed because of the small sample size of our series and its retrospective nature. Moreover, multivariate analysis to identify predictive factors of recurrence was not possible due to the absence of tumoral recurrence in our sample. A multicenter prospective clinical trial is needed to confirm these results, establish adequate selection criteria, and establish prioritization policy for patients with iCCA or HCC-CC awaiting LT (probably similar as we do with patients with HCC). This clinical trial (NCT02878473) is currently in progress and initial outcomes are expected in 2026.29 Until further investigation and waiting for confirmation of previous results, LT should be carefully indicated in iCCA and HCC-CC.

DisclosuresThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sources of fundingThe authors declare no funding.

Ethical approvalThe approval of the Ethics Committee of the “Doce de Octubre” university hospital was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data availability statementThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.