Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) is the most common bariatric surgery worldwide and has shown to cause de novo or worsen symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Esophageal motility and physiology studies are mandatory in bariatric and foregut centers. The predisposing factors in post-SG patients are disruption of His angle, resection of gastric fold and gastric fundus, increased gastric pressure, resection of the gastric antrum, cutting of the sling fibers and pyloric spasm. There are symptomatic complications due to sleeve morphology as torsion, incisura angularis stenosis, kinking and dilated fundus. In this article, we present recommendations, surgical technique and patient selection flow diagram for SG and avoid de novo or worsening GERD.

La gastrectomía vertical (GV) es la cirugía bariátrica más común realizada en el mundo y asimismo ha demostrado en el transcurso de estos años tener como consecuencia la aparición o empeoramiento de síntomas de reflujo gastroesofágico (RGE). Es imprescindible que en los centros de alta volumen de cirugía de foregut o intestino anterior se realicen estudios de motilidad y fisiología esofágico. En el paciente post GV, los factores condicionantes para desarrollar RGE son la desaparición del ángulo de His, del pliegue gástrico antirreflujo y del fondo gástrico, aumento de la presión intragástrica, resección forzada del antro, sección de las fibras sling y espasmo pilórico. A continuación, están descritas nuestras recomendaciones, técnica quirúrgica y flujograma de selección del paciente ideal para GV y evitar la aparición o empeoramiento de RGE.

Vertical sleeve gastrectomy is the most common bariatric surgery performed in the world, and has also been widely shown to produce symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) or worsen existing reflux.1,2

There are many bariatric surgical techniques. The selection of patients for each technique will depend on their metabolic characteristics, the degree of obesity, metabolic syndrome or weight gain. Often the patient's preference determines the choice of technique (usually “gastric sleeve”).3,4

For this reason, in our centre specialised in anterior digestive tract surgery (foregut) patients are evaluated for symptoms of reflux, regurgitation, heartburn or dysphagia, with a complete endoscopic, radiological and oesophageal motility study that is performed routinely for a more precise selection of patients before surgical treatment and so that the chosen technique has the best success rate and the lowest probability of long-term complications. In this sense, the patient with reflux or with a high probability of developing it is directed towards the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

This article will present the anatomy of the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ), the changes that would explain the appearance of reflux symptoms, the pre- and postoperative comparative studies, together with the visualisation of the changes that occur with respect to the volume and morphology of the sleeve through the volumetry.

Anatomy and physiology of the normal gastro-oesophageal junction and in the gastrectomised patientThe GOJ is the part of the digestive tract that is in a transitional space between the thorax and the abdomen subjected to different pressures and that has an important range of motility produced by swallowing. The antireflux mechanism is multifactorial, which makes the investigation of its pathology and the approach to its treatment complex.5

The GOJ is anatomically composed of the abdominal oesophagus, the angle of His, the gastric fundus, the Sling fibres, and the Clasp fibres.6 All these structures must be in their normal anatomical position to constitute a perfect gastro-oesophageal antireflux mechanism. The support elements of this mobile area would be provided by the phrenoesophageal ligament, the diaphragmatic crura, the pars condensate, the lesser omentum, the fundus phrenic ligament and the short vessels. When one of these structures fails, the crura can dilate, producing a sliding hiatus hernia that will produce gastroesophageal reflux. The abdominal portion of the oesophagus (4 cm) is subjected to a series of abdominal pressures, gastric pressures and GOJ pressures that create an area of high pressure that would constitute the so-called lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS), which would be a sum of forces rather than a specific muscle sphincter.7

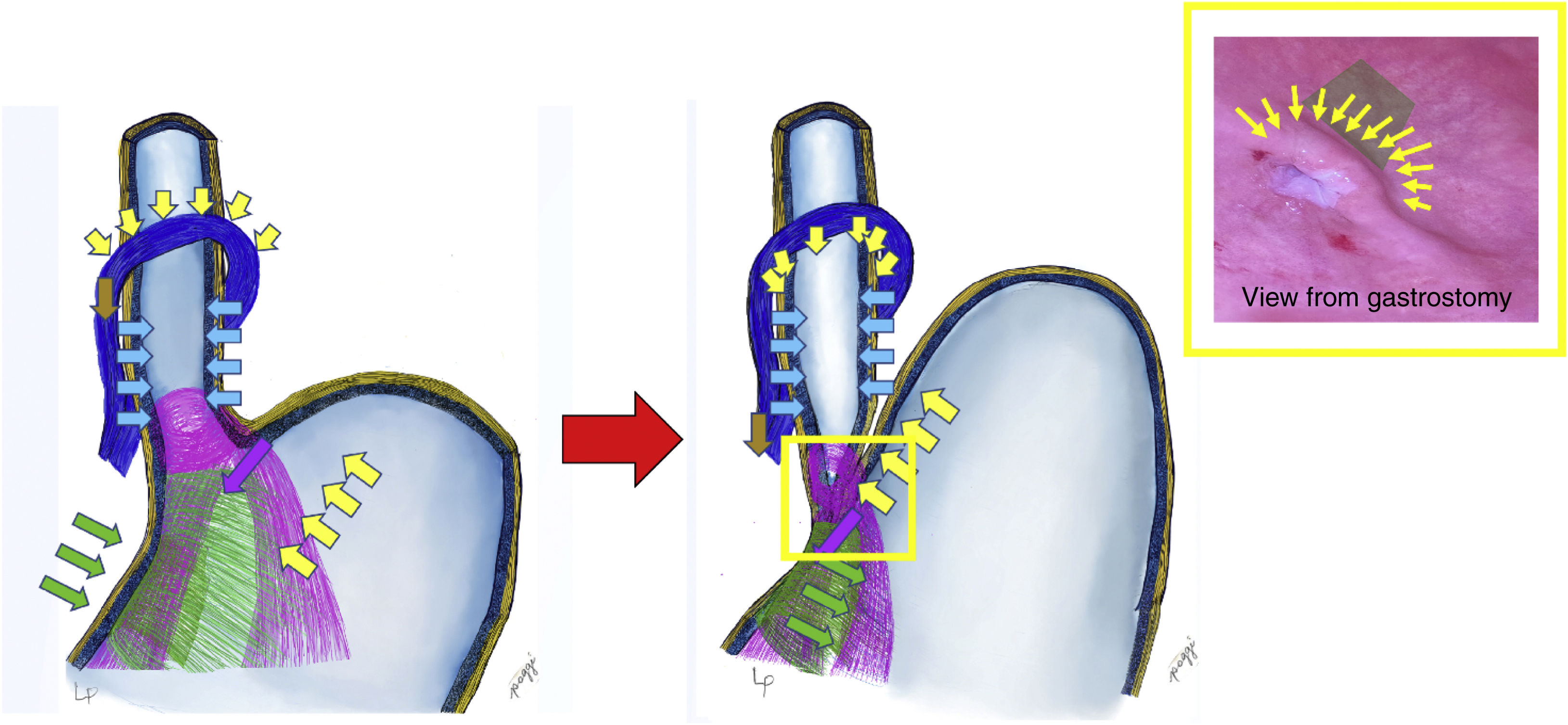

The anatomical, regular and physiological nature of these structures constitutes an anti-reflux valve mechanism, allowing the passage of food from the oesophagus to the stomach and preventing its return8 (Fig. 1). In this mechanism, the Sling fibbers (purple in the illustration) have a highly unique arrangement in the stomach, they go along the anterior wall, rotate around the oesophagus like a loop and go down the posterior slope, fixing on the incisura angularis. They generate the angle of His and act by moving the wall of the oesophagus downward and to the right (purple arrows); This is complemented by Clasp-type fibres (green), which contract by taking the right edge of the oesophagus in the opposite direction, from the right to the left, closing the cardia (green arrows). This closure is complemented by the action of the pressure of the gastric fundus on the oesophagus (complying with Pascal's law [yellow arrows]), which compresses the oesophagus at the level of the oesophagogastric transition, thus completing the antireflux mechanism.9 We repeat that the diaphragmatic crura also participates, it contracts from top to bottom and from front to back, acting as an important part of the antireflux mechanism (according to Zifan, 85%); We also wish to reiterate that any dilation of the crura produces stomach slippage and hiatus hernia, necessarily and obligatorily generating gastroesophageal reflux.

When one swallows, the sequence would be that the oesophagus propels the food bolus towards the stomach, producing the relaxation of the sling and clasp fibres, opening the cardia and allowing the food to enter. The antireflux mechanism springs into action as soon as what is ingested increases intragastric pressure (this happens when the volumes reach the limit, more than 750 ml), preventing the food backing up from the stomach into the oesophagus. It is in this situation where the clasp and sling fibres contract, closing the cardia with the help of the increase in intragastric pressure and the elevation of the gastric fundus, compressing the oesophageal wall and generating a gate valve mechanism (Fig. 1).6

The representation of the gate mechanism seen from inside the stomach is called the flap valve (yellow box in Fig. 1), which is what we try to reproduce in surgery when it has been lost, generating reflux and in this way re-establishing functionality and LOS competence.10 This level is equivalent to the transition zone from the entrance of the oesophagus to the stomach, where the intragastric pressure would act in addition to the other forces mentioned, generating the gate or check valve effect on the portion of the oesophagus that is inside the stomach wall.6 This is what Jobe et al.8 refer to, and what is mentioned by Tom DeMeester as the high pressure zone.

The gastrectomy technique would lead to sectioning of the structures involved in the anti-reflux mechanism. These changes produced by the resection of the stomach and gastric fundus would lead, first of all, to a decrease in the existing pressures on the LOS,11 turning it into an incompetent cardia given that the sling fibres, because they are sectioned, cannot contract efficiently. Likewise, the absence of the gastric fundus causes the angle of His to be lost, also losing the gate mechanism, and the reduction in the volume of the stomach would cause intragastric pressure to increase, producing an opening of the greater cardia, leaving it permanently open or yawning, causing incompetence of the antireflux mechanism and promoting the return of gastric contents towards the oesophagus, including bile reflux (Fig. 2).

Anatomical-functional factors that cause gastro-oesophageal refluxThe anatomical alterations that would cause gastroesophageal reflux are known:

- •

Hiatus hernia.

- •

Disappearance of the abdominal oesophagus.

- •

Disappearance of the gastric fundus.

- •

Hypotension of the high-pressure area or LOS.

- •

Permanent loss or opening of the His angle.

- •

Increase in intra-abdominal pressure.

- •

Increase in intra-gastric pressure.

- •

Inversion of oesophagogastric pressure gradient.

- •

Hyper acidity.

- •

Abnormal increase of the frequency of transitory relaxations.

- •

Lack of resistance of oesophageal mucosa to acid.

- •

Delayed gastric emptying.

- •

Alterations produced as a consequence of gastric surgery:

- o

Resection of gastric fundus.

- o

Stenosis of the gastric notch or body.

- o

Stomach outflow obstructions.

- o

Gastroparesis.

- o

Progressive oesophageal dysmotility.

- o

Oesophageal spasm.

- o

For the analysis of all the factors considered in the previous paragraph, a comprehensive study is required so that the functional state of the GOJ may be understood and the physiological alterations produced by the resection or the modification of the anatomy generated in the various surgical techniques may be interpreted.12,13 Evaluation must be comprehensive, i.e., complete, analysing the oesophagus by fluoroscopy, endoscopy and oesophageal motility (manometry-pHmetry-impedance).

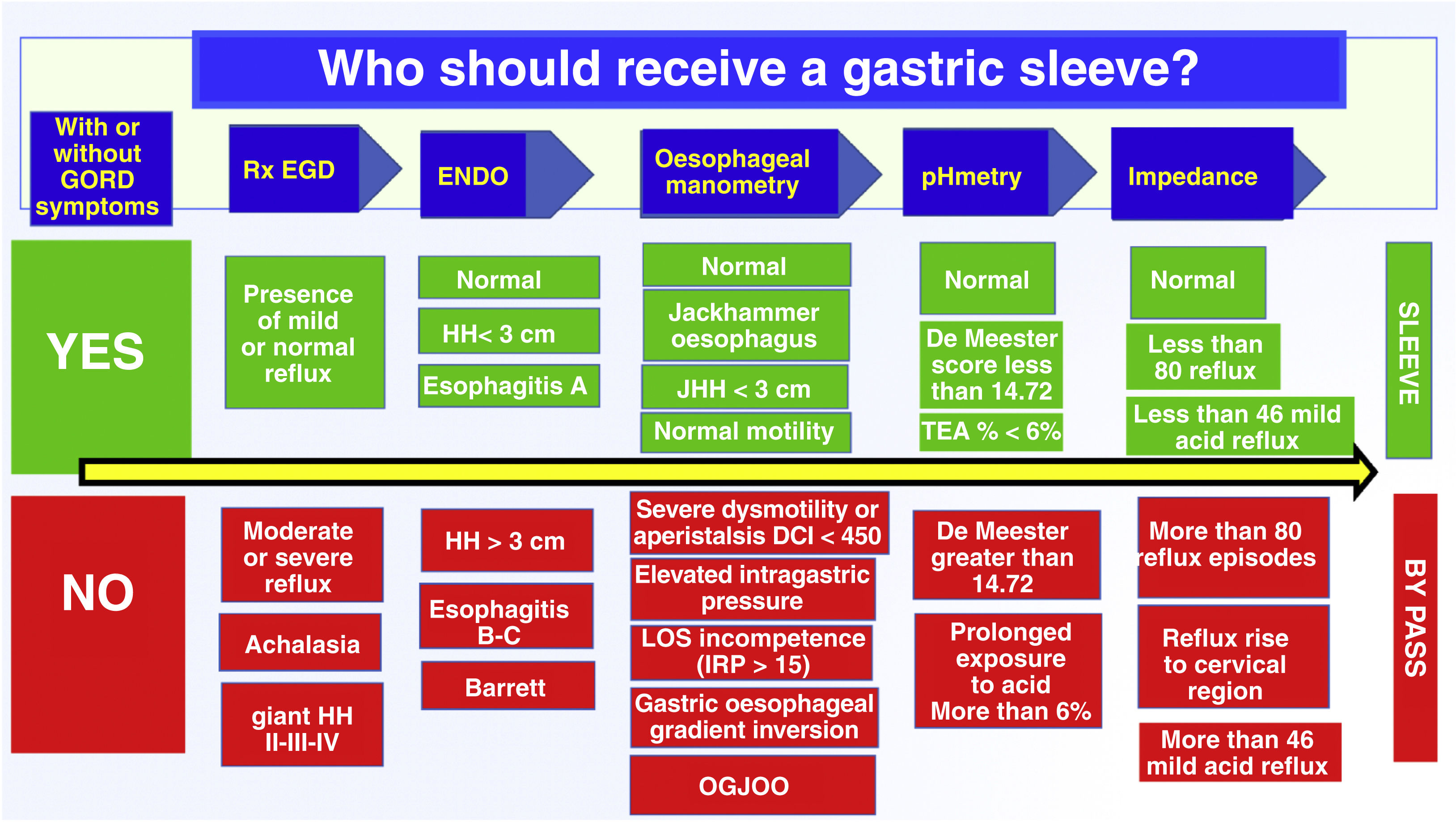

The results of these tests would allow us to objectively be familiar with pathologies that could cause reflux, such as dysmotility, achalasia, Jackhammer oesophagus or the pathology recently described as oesophageal gastric juntion outflow obstruction [OGJOO]) in both pre and postoperative bariatric surgery patients.14

By complete study we refer to the ideal, which includes: high-resolution oesophageal manometry, 24-h oesophageal pH and impedance measurement, oesophageal fluoroscopy, gastric emptying using scintigraphy, and upper endoscopy.15 Other techniques to use in the preoperative period of non-mandatory revisional surgery may be: endoFLIP and volumetrics using 3D reconstruction with tomography to determine the volume, morphology and type of surgery to which the patient with reflux was subjected.16,17

Pre and postoperative comparative resultsThese include pre- and postoperative results of patients undergoing vertical gastrectomy who agreed to undergo a complete study. There were 245 patients who had acceptable weight loss, with a decrease in BMI from 39.15 to 26.34. The results of each study conducted are presented below, together with an interpretation of them.

High resolution oesophageal manometryHigh-resolution manometry is the most important study of oesophageal motility and gives us the most information about the functional state of the swallowing process and oesophageal peristalsis. It allows us to detect and diagnose pathologies that may be a contraindication to performing a certain surgery, such as achalasia or severe reflux. The comparative value of pre- and postoperative manometry will allow us to evaluate the true action, effect or deterioration that surgery produces on the physiology of the oesophagus and the GOJ.

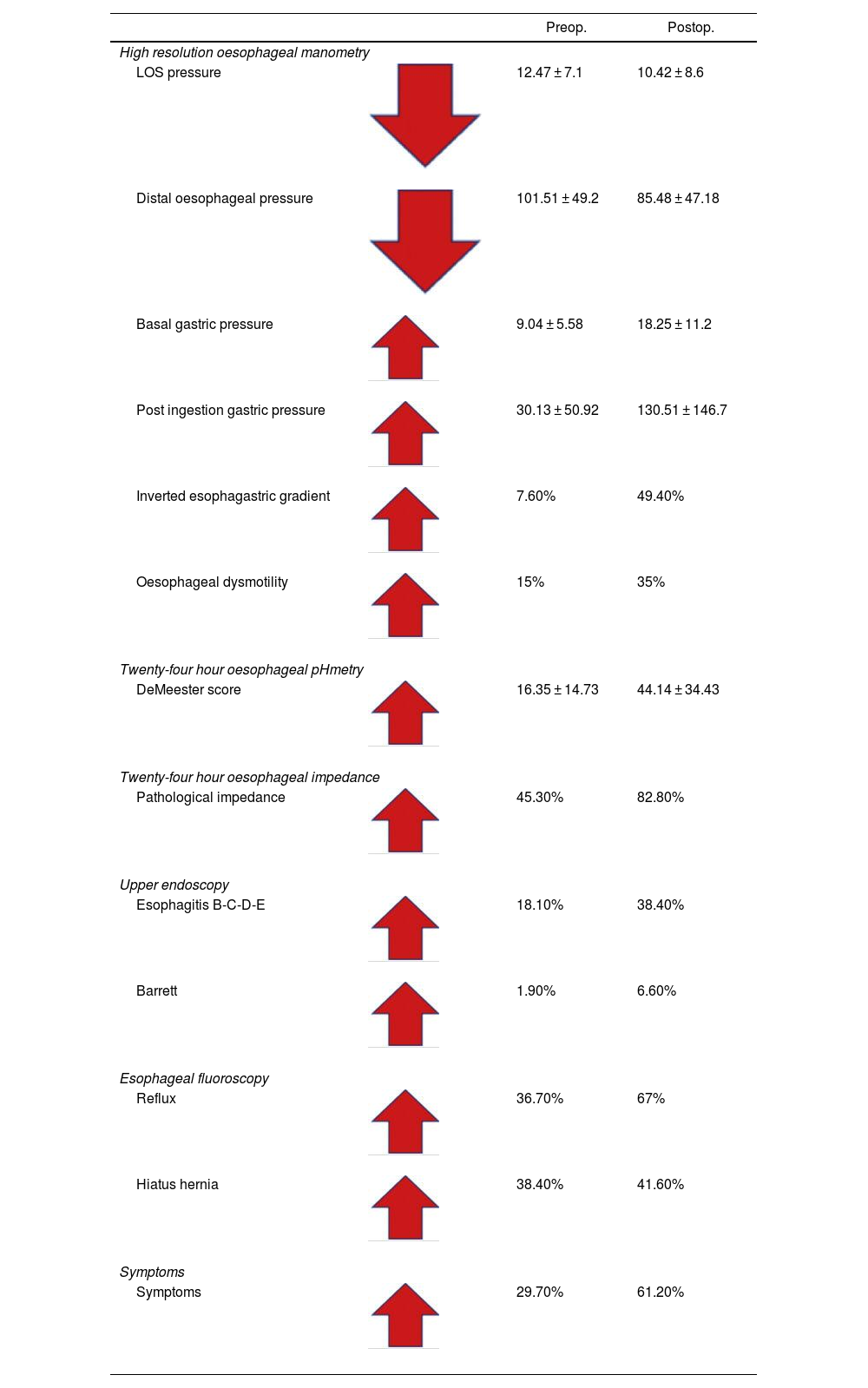

Results of pre and postoperative manometryThe most important findings are the changes that occur after vertical sleeve gastrectomy surgery in oesophageal manometry18 (Table 1).

Paired pre- and postoperative values of the complete study of fluoroscopy, endoscopy and oesophageal motility in vertical gastrectomy patients.

| Preop. | Postop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High resolution oesophageal manometry | |||

| LOS pressure | 12.47 ± 7.1 | 10.42 ± 8.6 | |

| Distal oesophageal pressure | 101.51 ± 49.2 | 85.48 ± 47.18 | |

| Basal gastric pressure | 9.04 ± 5.58 | 18.25 ± 11.2 | |

| Post ingestion gastric pressure | 30.13 ± 50.92 | 130.51 ± 146.7 | |

| Inverted esophagastric gradient | 7.60% | 49.40% | |

| Oesophageal dysmotility | 15% | 35% | |

| Twenty-four hour oesophageal pHmetry | |||

| DeMeester score | 16.35 ± 14.73 | 44.14 ± 34.43 | |

| Twenty-four hour oesophageal impedance | |||

| Pathological impedance | 45.30% | 82.80% | |

| Upper endoscopy | |||

| Esophagitis B-C-D-E | 18.10% | 38.40% | |

| Barrett | 1.90% | 6.60% | |

| Esophageal fluoroscopy | |||

| Reflux | 36.70% | 67% | |

| Hiatus hernia | 38.40% | 41.60% | |

| Symptoms | |||

| Symptoms | 29.70% | 61.20% | |

The preoperative LOS pressure is normal, with an average result of 12.47 ± 7.1 mmHg, compared to that of the postoperative, with an average result of 10.42 ± 8.6 mmHg (low evident LOS pressure), which can reach values below 6 mmHg, tending to be hypotensive and showing incompetence, especially in the presence of a hiatus hernia18 (Table 1).

Distal oesophageal pressure had a preoperative value of 101.51 ± 49.2 mmHg and a postoperative value of 85.48 ± 47.1 mmHg, also showing a deterioration in oesophageal body pressure.18

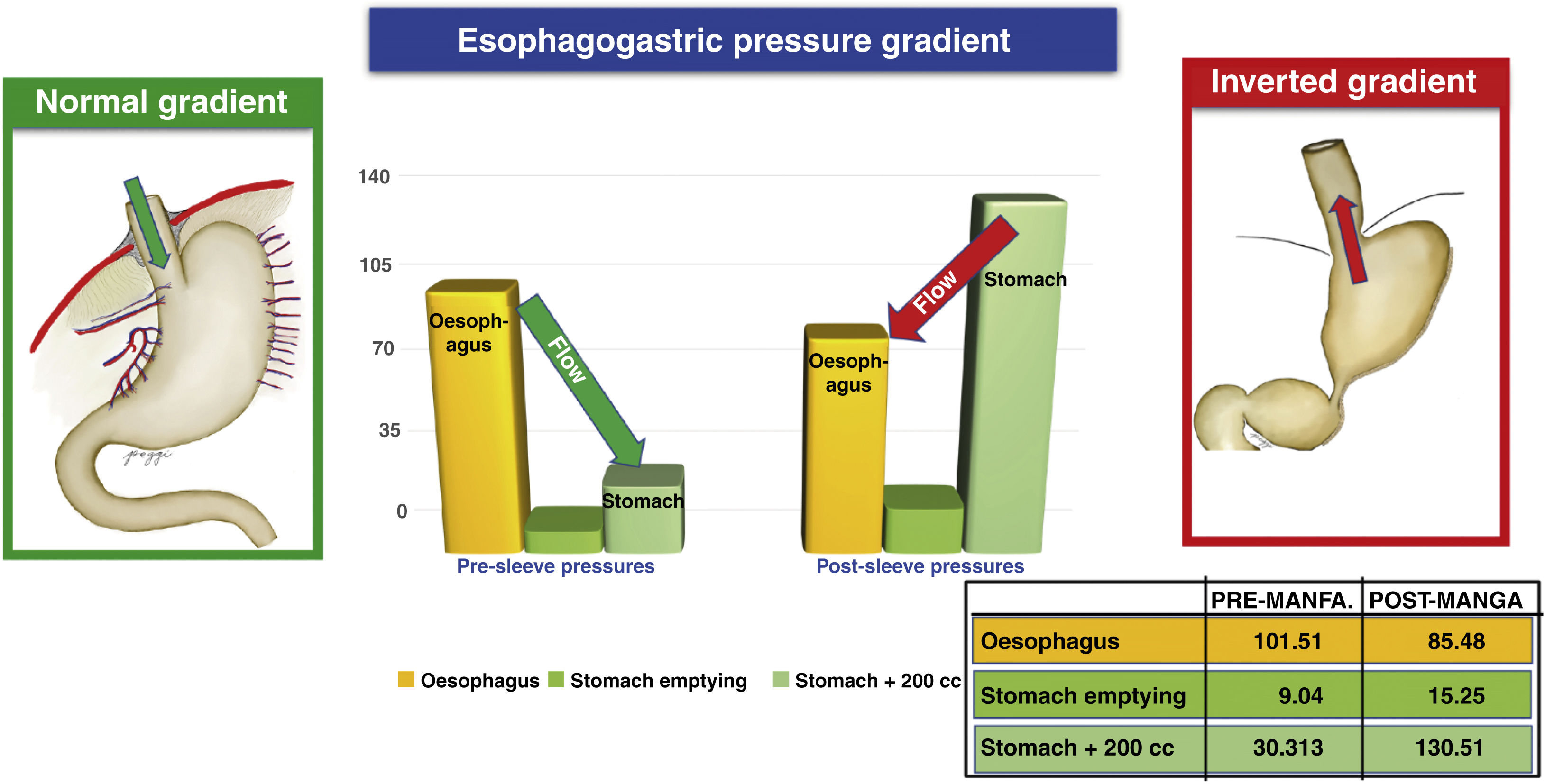

Intragastric pressure was evaluated in two ways: the first was by measuring the basal pressure with an empty stomach in the pre- and postoperative period, finding average values of 9.04 ± 5.58 mmHg in the preoperative period and 18.28 ± 11.2 mmHg in the postoperative period (probably related to the decrease in gastric volume). The second way in which we evaluated this parameter was to measure the intragastric pressure after ingesting a glass of water, finding that this post-ingestion pressure of liquid was 30.13 ± 50.9 mmHg preoperatively and 130.51 ± 146.7 mmHg in the postoperative period, which translates into an increase from 18 to 130, approximately 7 times its baseline value, as a consequence of the reduction in gastric volumen.18

The normal oesophagogastric gradient occurs when the pressure of the oesophagus is greater than that of the stomach, translating into a flow in the direction of the oesophagus to the stomach. The inverted oesophagogastric gradient occurs when the pressure of the oesophagus is lower than that of the stomach, resulting in an inverted flow from the stomach towards the oesophagus (gastro-oesophageal reflux). Our results show this, with the inverted gradient occurring in 7.6% of patients preoperatively and increases to 49.4% of patients postoperatively. This phenomenon of gradient inversion constitutes another major factor for the production of reflux18 (Fig. 3).

Due to the nature of the type of surgery, an increase in baseline and post-ingestion gastric intraluminal pressure is common (due to the decrease in stomach volume).18 This increase in pressure is one of the mechanisms responsible for the pathophysiology of post-sleeve reflux, because it alters the pressure gradient between the stomach, the LOS and the oesophageal body, generating a return or regurgitation of gastric contents towards the oesophagus. The inversion of the gradient, according to Poggi et al.,19 ranges pre- and postoperatively from 6% to 48%, respectively.

Dysmotility is present in 15% preoperatively, and in the postoperative period it increases to 35%, demonstrating that there is deterioration in motility that will condition the reflux, because after evaluating all our patients we believe that dysmotility never improves, it always worsens with vertical gastrectomy.18

After analysing all the reflux conditioning factors evaluated by manometry, our reflux results by manometry would be 60.3%, with de novo reflux being 34.6%18 (Table 1).

According to our results, possible predictors of worsening reflux and de novo reflux would be LOS hypotension, elevated preoperative baseline gastric pressure, inverted oesophagogastric gradient, and dysmotility. Currently, digestive neuromotility study groups grade oesophageal peristalsis with analysis of distal contractile interval (DCI) and elevated integral relaxation pressure (IRP), which is related to LOS competence in pathologies such as achalasia and OGJOO.18

Preoperative findings and possible diagnosesThere are functional states of the oesophagus that we must take into account among candidates for bariatric surgery. These patients could be in a potential transitional state of generating reflux in the postoperative period, and these are precisely the cases detected using the Chicago IV classification.20,21

Cases that should be detected in order not to perform a gastric sleeve:

- •

Ineffective oesophageal motility (oesophageal dysmotility). Contraindication of gastric sleeve.

- •

Gastro-oesophageal junction outflow obstruction (OGJOO).

- •

Asymptomatic in some cases, which may be related to hiatus hernia, early developing achalasia or a functional problem. Gastric sleeve is not recommended.

- •

Jackhammer hypercontractile oesophagus (relative contraindication for gastric sleeve). Related to substernal pain. You are at risk of fistula.

- •

Distal oesophageal spasm. Related to gastro-oesophageal reflux. Relative contraindication of gastric sleeve.

- •

Achalasia. Absolute contraindication of gastric sleeve.

- •

Hiatus hernia that must be corrected and, at the same time, is one of the most frequent complications of the gastric sleeve that causes GOR disease due to the sleeve slipping into the thorax.

The pHmetry study is performed together with the oesophageal impedance study with the same catheter that allows us to measure the exposure of the acid of the distal oesophagus to a pH < 4 using pH sensors that are in the middle and at the tip of the catheter. The distal sensor is in the stomach and the proximal sensor is 5 cm above the upper edge of the LOS previously determined by manometry. pHmetry is measured through the DeMeester score (normal value: 14.72) and the percentage of time of exposure to acid (normal value: <4%) of the distal oesophagus.22

The 24 h oesophageal impedance is measured together with the pHmetry catheter through 6 pairs of sensors installed from 3 cm to 17 cm proximal to the upper border of the LOS. This study allows recording the number of reflux episodes (normal value: <80), the type of reflux, whether it is alkaline or acid, and the level of reflux rise to the cervical region.

Pre- and postoperative 24-h pH-impedance results of vertical gastrectomy (Table 1)The DeMeester score in the patients in the pre- and postoperative period was 16.35 ± 14.73 and 44.14 ± 34.43, respectively, that is, in the postoperative period these values tripled, expressing a pathological condition due to acid reflux. With this method, it is possible to diagnose pathological reflux in 82.81% in the postoperative period, with de novo reflux being 51.56%.

The preoperative acid exposure time was normal, with a value of 3%, and in the postoperative period it was pathological in 16% of the patients, showing, once again, an evident gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Oesophageal impedance showed that 82.8% of patients had postoperative reflux and 42.2% had de novo reflux.

These results demonstrate that, through the complete study with manometry, pHmetry and oesophageal impedance tests, with manometry we have enough evidence to consider that it is the only way to make an accurate and irrefutable diagnosis.

Importance of oesophageal endoscopy and fluoroscopy in the bariatric patientOesophageal fluoroscopyOesophageal fluoroscopy is not given its due value or importance in the literature. In our service, based on our results, our opinion differs. We usually have the same surgeon perform oesophageal fluoroscopy, thus obtaining the maximum information on oesophageal motility and function. In preoperative studies, visualising the hiatus hernia and reflux leads us to suspect motility problems. Likewise, in the postoperative period it allows us to evaluate the results of the surgery and rule out problems of strictures, leaks and reflux.

Upper endoscopyWe consider it mandatory to perform preoperative endoscopy to detect oesophageal pathology, Barrett's, oesophagitis, achalasia, oesophageal diverticula and gastric pathology such as benign GIST-type tumours or incipient malignant tumours that force us to reconsider surgery. Postoperative endoscopy follow-up is to detect signs of reflux related to moderate or severe erosive oesophagitis, Barrett's, and dysplasias.23 There is a suggestion that preoperative endoscopy may not be necessary in the case of bariatric surgery24,25; However, endoscopic follow-up is also recommended to detect slippage, Barrett's or reflux. There are studies of post-sleeve Barrett, as reported by Genco et al.26 and Iannelli et al.,27 with results of 17.4% and 18.8% of post-sleeve Barrett, respectively. Our results were 6.6% per year of patients with Barrett's oesophagus, and for our service Barrett's oesophagus is a formal contraindication. These cases can progress to severe dysplasia and cancer, and in our service we have had 2 patients with GOJ cancer.

3D-TC volumetricsIn the follow-up protocol we observed that a useful tool is tomography volumetry with 3D reconstruction. Through this procedure we can obtain results on the volume of the sleeve, its morphology, its technical defects and its sliding to the tórax.16,28 Below we describe the problems that would cause reflux, detectable by 3D-CT volumetry:

- a)

Slippage occurred in 72.4% of our operated cases, regardless of whether or not correction of the hiatus hernia was performed (Fig. 4A, where the line of staples goes above the diaphragm).16

Fig. 4.Illustration and 3D reconstruction of complications related to the appearance of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in sleeve gastrectomy. A) Intrathoracic slip. B) Dilation of the gastric fundus and oesophagus. C) Torsion. D) Stenosis/narrowing of the incisura angularis. In all cases slipping of the sleeve is seen.

(0.42MB). - b)

Dilation of the gastric fundus occurred in 22.4% of our patients generally due to dilation from a stenosis of the body or due to an unresected gastric fundus. Global sleeve dilation occurred in 64.7% of operated cases, which indicates a long-term growth or increase in sleeve volume over time and is related to regaining weight (Fig. 4B–D).16

- c)

Oesophageal dilation occurred in 27.6% of those operated on in our group, which is explained by forced feeding and increased gastric pressure. When trying to overcome the elevated gastric pressure the oesophagus became dilated during the attempt to pass the food into the stomach. This leads to gastro-oesophageal reflux with severe oesophageal dysmotility and progressive deterioration of oesophageal peristalsis. Severe oesophageal dysmotility never improves, it always worsens (in Fig. 4B–D the oesophagus is seen dilated in 3D).11,16

- d)

Spiral or corkscrew torsion occurred in 8.6% of our cases, because the gastric tube rotates on its own axis and adopts a spiral shape like a corkscrew. This is due to irregular and asymmetrical stapling. Clinically it is expressed as digestive intolerance with frequent vomiting and generally massive weight loss (Fig. 4C). All patients with this complication will develop severe intractable reflux, and usually undergo sleeve revision to bypass surgery.16

- e)

Stenosis of the incisura angularis occurred in 44% and stenosis of the body occurred in 7.8% of our research group. This alteration occurs when the stapler sticks too much at the level of the incisura angularis or when there was an asymmetric resection of the stomach (Fig. 4B–D).16

- f)

Kinking's presentation occurred in 75.9%. A severe acute angle is formed between the antrum and the gastric body at the level of the incisura, creating partial obstruction when it breaks on itself and prevents the passage of content from the proximal to the distal stomach, generating vomiting and reflux.16

Vertical gastrectomy produces anatomical alterations in the GOJ that generates alterations in the entire antireflux valve mechanism. This technique promotes the appearance of reflux and the deterioration of all the anti-reflux functions of the GOJ.

Taking into consideration all the above research, we wished to create a flowchart to help us choose which bariatric surgical technique to use in obese patients, mainly deciding between gastric sleeve and bypass. This entire analysis is based on our results of manometry, pHmetry, impedance, oesophageal fluoroscopy and upper endoscopy, with the main interest of identifying patients who have a low probability of developing reflux versus those who have a very high probability of presenting reflux postoperatively; We believe that it is a good way to prevent the patient from having revision surgery for intractable reflux in the future (Fig. 5).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Poggi Machuca L, Romani Pozo D, Guerrero Martinez H, Rojas Reyes R, Dávila Luna A, Cruz Condori D, et al. Posibles aspectos técnicos implicados en la aparición de RGE tras gastrectomía vertical. Consideraciones para la técnica quirúrgica. Cir Esp. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2023.02.005