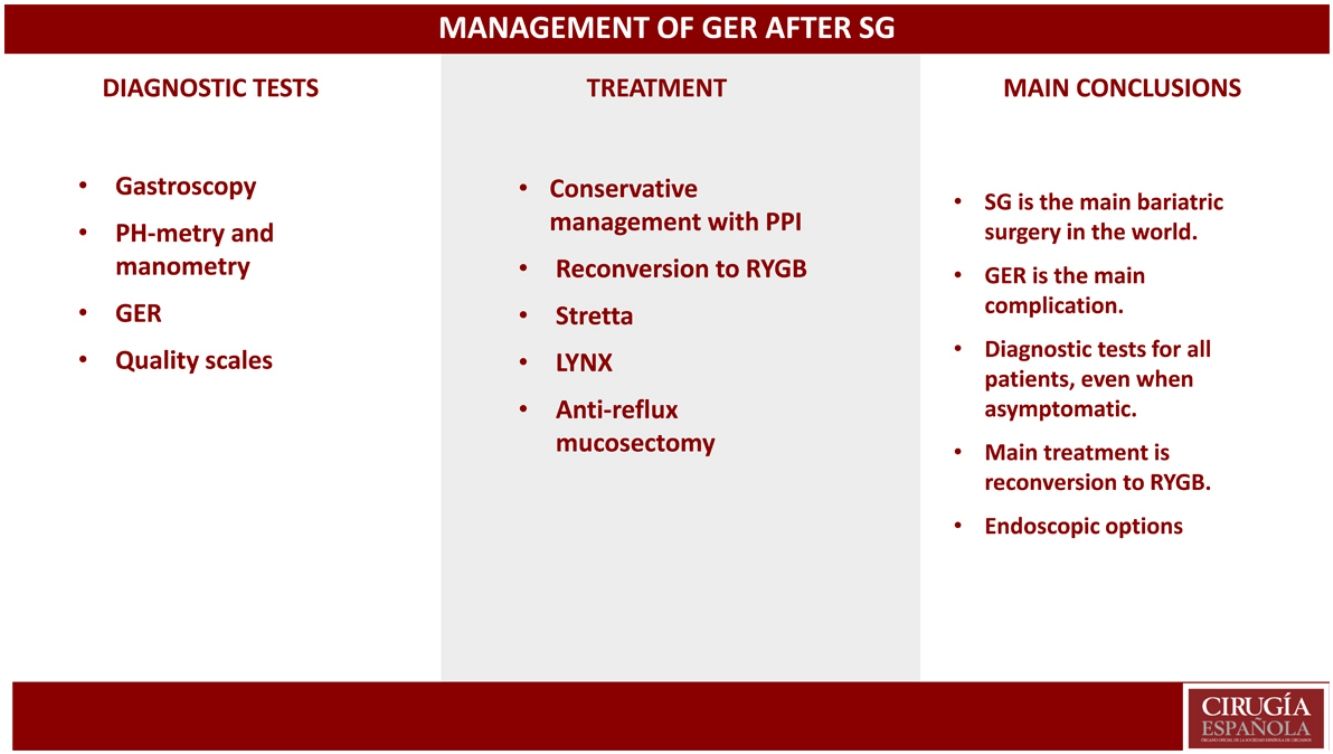

VSG is the most used surgical procedure in the world. Among the main complications linked to this procedure is GERD. It is apparent that endoscopic control protocols should be undertaken in all patients recovering from a VSG procedure. This is particularly key when taking into account the large number of patients suffering from GERD that show no symptoms, a situation that in many cases leads to severe esophagitis or even adenocarcinoma. Once the pertinent diagnostic tests have been carried out, the specialist should seek a conservative medical treatment including PPI. In the event that this treatment should fail, the next step to be considered should be a surgical procedure. In this case, the ideal procedure would be a reconversion to gastric bypass due to its low-risk and its results. There are other alternatives such as the Stretta, Linx or ARMS procedures; however, further research is necessary to prove their reliability.

La gastrectomía vertical es la técnica de cirugía bariátrica más realizada en el mundo. Una de sus principales complicaciones es el reflujo gastroesofágico. A la vista de estos resultados queda claro que deben realizarse de forma protocolizada controles endoscópicos en todos los pacientes intervenidos de gastrectomía vertical sobre todo si tenemos en cuenta la gran cantidad de pacientes asintomáticos que presentan dicha patología y que en muchos casos pueden desencadenar esofagitis severas e incluso adenocarcinomas. Una vez realizadas las pruebas diagnósticas adecuadas, debe iniciarse tratamiento médico conservador con IBP y hacer un seguimiento estricto de estos pacientes. En caso de que fracase el tratamiento conservador, debe plantearse un tratamiento quirúrgico. La reconversión a Bypass Gástrico es la cirugía de elección por su seguridad y resultados. Existen otras técnicas endoscópicas como el Stretta o Linx que pueden plantearse como alternativas, aunque todavía hacen falta más estudios que demuestren su efectividad.

As stated in previous chapters, pathological obesity has progressively increased in recent years to reach epidemic rates. This has led to a significant increase in surgeries performed for this pathology. Likewise, obesity is considered an important risk factor for the development of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) symptoms,1 and the solution in many cases has been to perform a bariatric procedure that would resolve the underlying pathology and thereby avoid the development of GER. However, not all bariatric techniques are the same in terms of results, complications, risks, etc. In many cases, bariatric surgery can be considered counterproductive, especially if we consider that not all patients have been studied for GER before undergoing bariatric surgery. Therefore, in many instances we do not know the baseline situation of this pathology, and it is difficult to indicate an adequate bariatric technique.

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is currently the most widely used bariatric technique in the world.2 As a result, over time we have witnessed an increase in the number of patients with complications secondary to this procedure, in most cases associated with GER.

If we closely analyze the technique, this procedure can alter the normal anatomical and physiological antireflux architectures of the esophagus due to reduced gastric compliance, increased intragastric pressure, and anatomical alterations to the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and angle of His.3 These changes increase the reflux of gastric contents into the lower esophagus, significantly increasing esophagitis, the risk of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and even adenocarcinoma.4 According to some authors, these factors that exacerbate GER could be counteracted by accelerating gastric emptying and the weight loss that occurs after surgery, which would explain the improvement in GER 3 years later. However, this exacerbated gastric emptying can be associated with a “fixed” pylorus in 80% of cases and the presence of bile in the stomach in 40%, 10.5 years after surgery.5 Studies with scintigraphy scan show bile reflux rates of 31.8% after LSG, which could be the cause of esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus.6

With the scenario described above, we are faced with a widely extended bariatric technique with evident refluxogenic potential. Likewise, LSG is associated with significant weight regained over time, which is another determining factor for worsened GER.

Diagnostic tests in the follow-up of patients treated with LSGWith all the data described above, it seems clear that strict follow-up of these patients must be planned, since the appearance of GER seems inevitable.

It is necessary to determine which diagnostic tests should be performed in patients treated with LSG in order to be able to anticipate these complications and establish an appropriate treatment. This is especially true when we consider that many patients present postoperative de novo GER that is asymptomatic and will not make us suspect the existence of a pathology. To this we must add, as we mentioned earlier, that many of these patients have no preoperative studies, and we have no information about their baseline situation.

The definitive diagnosis of GER is generally established according to four criteria: symptoms, endoscopic findings, digestive radiology, and esophageal physiology studies, such as high-resolution manometry and esophageal pH-metry.7,8

Quality scalesQuality scales allow us to objectively quantify patient symptoms and make comparisons following the same parameters.

The GerdQ questionnaire, validated by Jonasson et al.9 in 2009 at King’s College in London and later by Pérez-Alonso et al.10 in 2009, has been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of GER and can reduce the use of digestive endoscopy, optimizing the use of resources.

In any case, these scales allow us to make a clinical diagnosis, but they are insufficient when it comes to identifying the severity of esophageal lesions.

GastroscopyThe systematic performance of preoperative endoscopy in patients before bariatric surgery is more than disputed, and the same is true for the postoperative follow-up of these patients.

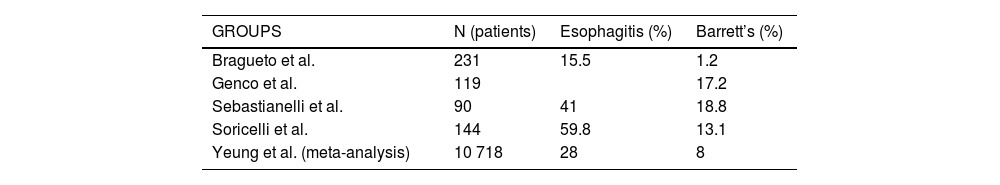

There are several medium- and long-term studies11–15 that report the appearance of BE and esophagitis on gastroscopy (Table 1) with percentages that are not at all negligible. Many of these patients did not present GER symptoms, so these results suggest the need for gastroscopy in all patients, regardless of symptoms.

Because the use of LSG has spread extensively around the world, it is essential to determine how follow-up studies should be conducted and with what frequency, especially in young patients with many years ahead for complications to develop. We do not know whether the progression to BE and adenocarcinoma occurs in the same way in sleeve gastrectomy patients compared to the rest of the population. Likewise unclear is the decision to be made after the diagnosis of BE in a patient with sleeve gastrectomy: follow-up or conversion to gastric bypass?16 What seems clear is that it is essential to perform postoperative gastroscopies in all patients treated with LSG in order to propose an appropriate therapeutic approach afterwards. There are therefore multiple studies that relate LSG to the development of reflux, esophagitis and BE, with a high rate of asymptomatic patients, so it seems important to recommend endoscopic follow-up studies starting 5 years after surgery in all patients, regardless of the presence or absence of GER symptoms.17

PH-metry and manometryIn recent years, several studies have investigated the pathophysiological effects of bariatric surgery on GER in patients after LSG. Raj et al. describe a significant increase from 10.9 ± 11.8–40.2 ± 38.6 points in a population of 30 patients who underwent LSG.18 Using conventional manometry, Braghetto et al. reported that LES pressure after laparoscopic gastric sleeve is reduced due to the division of the “slingfibers” of the esophagogastric junction when stapling close to the angle of His.19 Hampel suggests that the lack of gastric compliance after fundic resection and removal of the angle of His would increase basal gastric pressure after LSG, creating an increase in intraluminal pressure that would exceed the resting pressure of the LES.20 This explains the increase in the percentage of patients presenting inversion of the esophagogastric gradient.

Previous studies support that manometry and PH-metry may play an important role in the diagnosis of GER in patients undergoing LSG and should be considered in the follow-up algorithms for these patients.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)EGD can be used to diagnose complications such as hiatal hernia (HH), stenosis and dilatation of the fundus, so it can be useful for surgical planning. Discrepancies have been observed between diagnostic tests when determining the presence or absence of HH. It seems that endoscopy can overestimate its presence, while EGD is more reliable.21 In any case, this type of barium studies should be considered whenever reoperation for GER is considered in this type of patient.

Treatment of a patient with ger after LSGAs previously stated, strict clinical follow-up should be incorporated into the control strategy of patients who have undergone LSG, since we know that a significant number of patients will develop GER. Basically, the dilemma is this: when and with what frequency should endoscopy, functional tests and barium studies be performed? Currently, there are no sufficiently powerful studies to support follow-up. What seems evident is that follow-up after the 5th year is highly recommended, as Ferrer et al.17 have already proposed.

Once the appropriate diagnostic tests have been carried out that lead us to the diagnosis of pathological GER, we must consider what the best therapeutic option is for the patient, at what point to consider revision surgery, and what type of technique to use.

In any case, it would be logical to propose a phased approach starting with conservative treatment that would enable us to observe the patient’s response from both a clinical and physiological standpoint.

Conservative treatmentConservative therapeutic options include lifestyle changes and medication (proton pump inhibitors [PPI]), which should be the first step. More than 50% of patients who undergo LSG require PPI during the immediate postoperative period. The number of patients requiring PPI may reach 26%, as shown in a large (n >11 000) nationwide retrospective study in France. Some studies suggest an initial dose of 40−80 mg of PPI twice daily for 2 weeks, followed by dose reduction. In patients with good results, the PPI dosage should be reduced as much as possible to limit potential PPI side effects.22

Conversion to gastric bypassConversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) has shown excellent results in terms of resolution of GER symptoms. Therefore, in the event of GER that is refractory to medical treatment after LSG, we should consider conversion to RYGB.23,24 Before making any surgical decision, it is essential to have the cause identified using the appropriate diagnostic tests, since GER in a patient operated on for LSG can have many causes. In most instances, it is simply due to the anatomical alterations of the technique itself, which entail increased pressure on the gastric tube, causing relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter and even the development of HH. In other cases, it is caused by a defect in the primary technique that causes stenosis, rotations, etc. Proper surgical planning is therefore important.

The study by Parmar et al. retrospectively reviewed 22 LSG that required conversion to RYGB. These authors observed improved GER in 100% of the patients, and 80% were able to discontinue PPI treatment.24 Abdemur et al. described complete resolution of GER after conversion from LSG to RYGB in 77% of patients and improved symptoms in 23%.25 Some studies have described a resolution of GER in 75% of patients one year after surgery. The risk of surgical complications is only slightly higher than in primary surgery, which leads us to be able to indicate it more generously.23,26–28

Regarding the associated HH repair during RYGB surgery, this has classically varied depending on its size and the surgeon performing the procedure. The study by Curell et al. is a retrospective analysis of 700 patients treated by LSG, 35 of whom present GER. During the conversion surgery, there were several patients who presented HH that were not repaired, since they were considered small in size, and conversion to RYGB was considered sufficent.29 Two of these patients required a third surgery to treat persistent HH, so examination and repair of the hiatus seem to be a key point in conversion surgery.29

Patients who undergo reconversion to RYGB after LSG usually regain weight. It seems that this is partly due to the fact that they tend to eat more after their symptoms improve,29 so this is an aspect to consider when establishing the malabsorptive component. This datum is important because these patients do not usually have a very high BMI when we operate, so we tend to perform less hypoabsorptive surgery, but we must consider future surgical outcomes.

Other techniquesApart from the surgical techniques themselves, other minimally invasive alternatives can be established for the treatment of GER in patients undergoing LSG. For many of these patients, this procedure was chosen due to age or comorbidities, yet on many occasions non-surgical techniques should be recommended.

Endoscopic methods for the treatment of GER include plication, lower esophageal sphincter augmentation with inert biopolymers, and thermal ablation. Several studies describe endoscopic reinforcement of the gastroesophageal junction in heterogeneous populations with GER symptoms, showing promising initial results.30,31

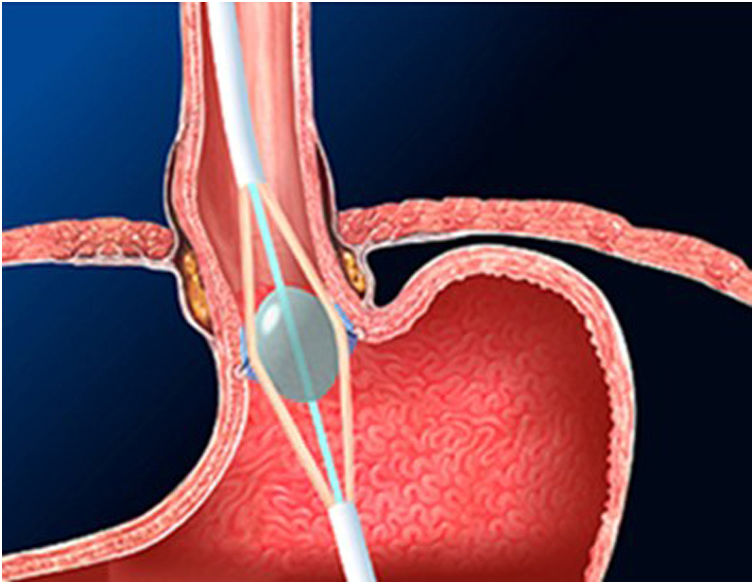

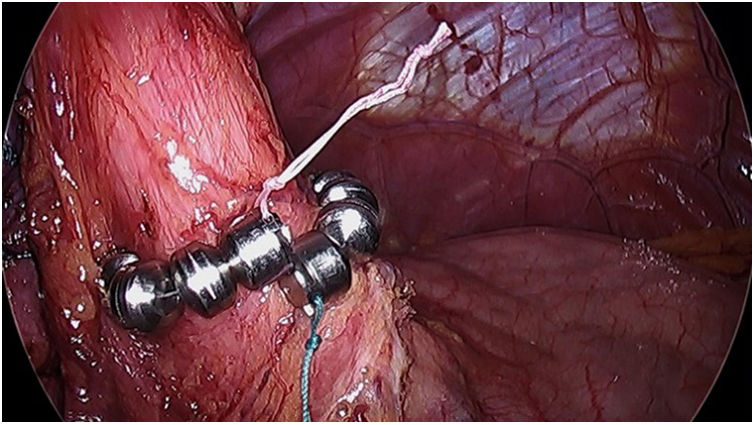

The Stretta technique (Figs. 1–3) is another endoscopic technique that is widely used in the US with good long-term efficacy. It involves performing radiofrequency in the muscle layer of the lower part of the LES through the endoscope. Thus, it is possible to reduce esophageal sensitivity to acid and decrease the distensibility of the gastroesophageal junction, resulting in symptomatic relief.

This technique would be indicated in patients with GER demonstrated in diagnostic tests, who do not present esophageal motility disorders or dysphagia and in the absence of a hiatal hernia greater than 3 cm. It would only be V pH and allowing the PPI dose to be reduced after SG. However, long-term studies in bariatric patients are necessary.32–34

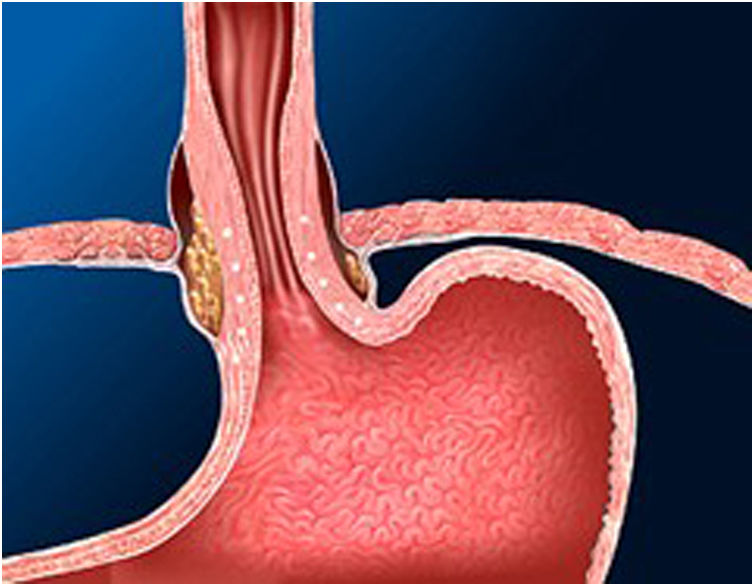

The magnetic sphincter (LINX) (Fig. 4) consists of a flexible ring with magnets that is placed around the LES, helping to keep it closed and preventing GER. In 2019, Hawasli et al. published a study of 13 patients who had said device implanted. One patient was excluded (loss to follow-up), and another required removal of the device due to dysphagia. In total, 5 patients experienced complete resolution of symptoms, while 6 patients experienced GER recurrence after 7 months without PPI.35

The indications are similar to those described for the Stretta technique. However, its placement is not recommended in patients with a BMI > 35. Although no specific studies have been conducted, a retrospective analysis of 70 patients observed that good results could not be demonstrated after said BMI.36

This technique is safe and can be considered an alternative to conversion to RYGB. However, a randomized prospective study is needed to guarantee the results and show long-term effectiveness.

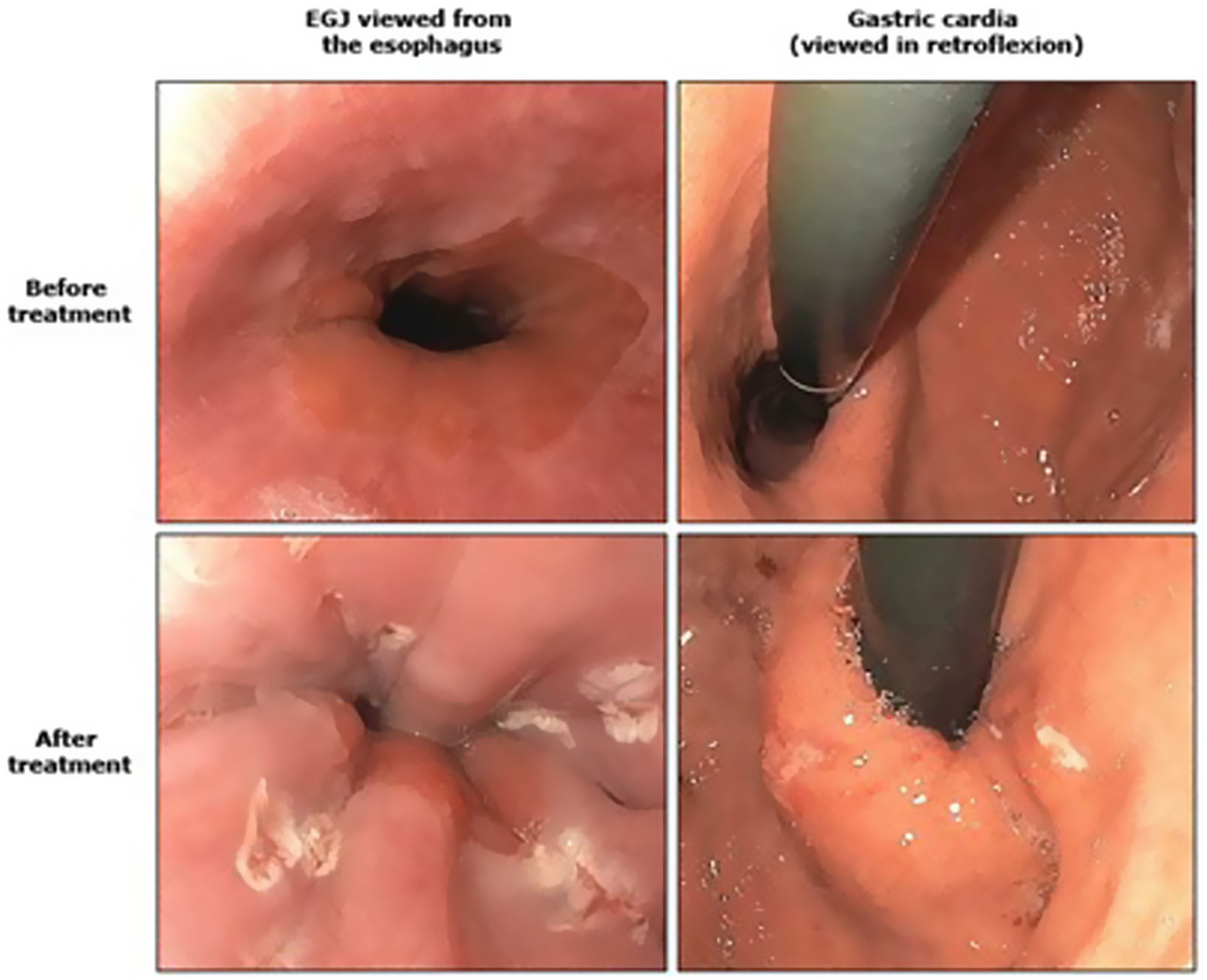

Antireflux mucosectomy (ARM) consists of submucosal dissection of the GEJ in the cardias, after which the scarring that occurs in the mucosal defect causes said area to contract and the esophageal lumen to narrow. The results described in the literature document an improvement in symptoms in 50%–70% of patients, but there are few studies with only small series of patients.37

ConclusionsLSG is the most widely used bariatric technique in the world. Numerous studies have shown the large percentage of patients who present either de novo GER or worsened reflux symptoms after performing this technique. In addition, it has been revealed that the findings found in the diagnostic tests do not always correlate with the symptoms. Although recent publications34 have shown a clear trend towards performing systematic postoperative endoscopies in all patients regardless of the symptoms, there is still no clear consensus regarding when or with what frequency they should be performed.

Many patients with GER will respond to PPI treatment. However, some of these patients will require some type of intervention. Revision surgery is an effective and safe procedure after LSG failure, and RYGB is the technique of choice in the presence of GER or esophagitis.

Other non-surgical techniques can be considered alternatives, including radiofrequency, LINX or antireflux mucosectomy, although more long-term studies are needed to validate the effectiveness of these procedures.