The aim of this study is to observe the psychological changes at one-year postop in a group of patients undergoing laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy (GVL) and multidisciplinary follow-up.

MethodsA total of 46 patients with a BMI-35 or higher, who were selected for GVL, completed psychological testing. After GVL surgery, patients received psychological, nutritional, and medical attention during 12 months, and they retook the same tests.

ResultsPsychological tests showed an improvement on almost all scales tested, except perfectionism. The most significant change was in the benchmark for Eating Disorders with an improvement of 89% for bulimia (P<.01), and 55% for body dissatisfaction (P<.01) and ineffectiveness (P<.01). In quality of life there was an improvement of 57% in the change in health status (P<.01).

ConclusionDuring our study, a protocol involving GVL and multidisciplinary follow-ups proved to be an effective intervention for improving bulimic symptoms and quality of living. The results of these psychological changes are similar to Roux-en-Y Gastric bypass but different to vertical banded gastroplasty or adjustable gastric band, according to previous studies. However, long-term studies are necessary to confirm this trend.

El objetivo del estudio es observar la evolución psicológica en un grupo de pacientes intervenidos mediante gastrectomía vertical laparoscópica (GVL) y tras un año de seguimiento multidisciplinar.

MétodosUn total de 46 pacientes con un IMC de 35 o superior completaron las pruebas psicológicas antes de la cirugía, y volvieron a cumplimentar dichas pruebas al año de la GVL (tras un seguimiento médico, nutricional y psicológico).

ResultadosSe observó una mejoría en todas las escalas analizadas, excepto el perfeccionismo. Los cambios más significativos se refieren al área de sintomatología alimentaria, con una mejora del 89% en bulimia (p<0,01), y un 55% en insatisfacción corporal (p<0,01) e ineficacia (p<0,01). Por otra parte, en el área de calidad de vida cabe destacar una mejoría del 57% en el cambio de salud (p<0,01).

ConclusiónLa GVL con un seguimiento multidisciplinar se confirma como una intervención efectiva para mejorar los síntomas bulímicos y la calidad de vida. Estos resultados son similares a los recogidos en diferentes estudios con bypass gástrico, y no tanto a otros con gastroplastia vertical anillada y banda gástrica ajustable. Sin embargo, son necesarios estudios a largo plazo para confirmar esta tendencia.

In this study, we present the preliminary results obtained in a group of patients operated on by vertical laparoscopic gastrectomy (VLG) and multidisciplinary monitoring (medical, nutritional and psychological). Our interest is to show the psychological changes of a group of patients treated with this technique, quantified by the results of a series of psychological tests performed before and one year after the operation. This type of study has already been performed in patients undergoing gastric bypass (GBP),1–15 vertical banded gastroplasty,10 or both surgeries.16,17 Other studies simply address bariatric surgery without specifying the technique used.1,18–27 We only found 2 articles comparing psychological improvement between VLG and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band.28,29

Most of the reasons given by patients at the time of surgery, and listed in preoperative psychological tests, deal with significant reductions in quality of life,1,6,9,16–20,23 body-image dissatisfaction and loss of control over body weight and food intake.2–7,17,20,30

Furthermore, we believe that VLG has important emotional implications regarding nutrition, because it is a very restrictive surgical procedure, associated with a strong decrease in ghrelin.31 Therefore, we decided to evaluate these variables (quality of life and eating symptomatology) in order to verify the suitability of VLG.

Patients and MethodsBefore recommending VLG surgery, patients are studied based on a comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment. We indicate this intervention for patients with a BMI of 35–40 (in special cases, up to 50). We use factors with a greater VLG outcome possibility: sweet-eaters, having a family history of morbid obesity (more than 2 obese members in first and second generation), insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular and musculoskeletal limitations for exercising after surgery. When patients meet 3 or more of these circumstances, they are advised to undergo GBP surgery.

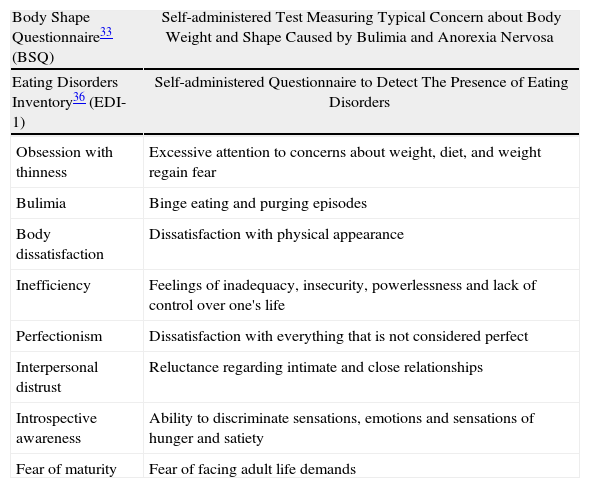

Psychological StudyDays before the surgery and after performing a complete psychological case history, patients complete a series of self-administered tests (either online or on paper): Edinburgh bulimia test32 (BITE); body shape questionnaire33 (BSQ); SF-36 health questionnaire34; quality of life index35 (QLI-SP); and eating disorder inventory36 (EDI-1) (Tables 1 and 2).

| Body Shape Questionnaire33 (BSQ) | Self-administered Test Measuring Typical Concern about Body Weight and Shape Caused by Bulimia and Anorexia Nervosa |

| Eating Disorders Inventory36 (EDI-1) | Self-administered Questionnaire to Detect The Presence of Eating Disorders |

| Obsession with thinness | Excessive attention to concerns about weight, diet, and weight regain fear |

| Bulimia | Binge eating and purging episodes |

| Body dissatisfaction | Dissatisfaction with physical appearance |

| Inefficiency | Feelings of inadequacy, insecurity, powerlessness and lack of control over one's life |

| Perfectionism | Dissatisfaction with everything that is not considered perfect |

| Interpersonal distrust | Reluctance regarding intimate and close relationships |

| Introspective awareness | Ability to discriminate sensations, emotions and sensations of hunger and satiety |

| Fear of maturity | Fear of facing adult life demands |

| Health Questionnaire34 (SF-36) | Test That Explores 8 Aspects of Health Status |

| Physical function | Degree of limitation to perform physical activity |

| Physical role | Extent to which physical health interferes with work and other daily activities |

| Pain | Pain intensity and its effect on normal work, both inside and outside the home |

| Health | Personal health assessment, including current health, expectations of future health and disease resistance |

| Vitality | Sense of energy and vitality to face fatigue and exhaustion |

| Social function | Limitations in normal social functioning due to physical and emotional problems |

| Mental Health | General mental health, including scales of depression, anxiety, behavior control and general wellness |

| Emotional role | Extent to which emotional problems interfere with work and daily activities |

| Quality of life index35 (QLI-SP) | Brief instrument measuring quality of life in terms of satisfaction |

After surgery, patients undergo individualized, dietary, nutritional and psychological monthly (for the first 6 months) and bimonthly medical monitoring with cognitive behavioral intervention. At 12 months, a psychometric reassessment (same test protocol) is performed.

Surgical TechniqueVLG is always performed by the same surgery and anesthesia team. We perform the gastrectomy using a 32 FR probe, from 4cm of the pylorus to the angle of Hiss using an ENDO GIA echelon flex and applying the “dog ear” technical variant. We perform a reinforcement Lembert invaginant suture along the entire staple line. Patients are treated with an enhanced postoperative recovery program: sitting after 2h, walking after 3h, liquid food after 5h and accompanied by breathing exercises. Hospital stay is for 48h.

Statistical AnalysisStatistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 11 package. Data are shown as mean±standard deviation (SD). For comparisons of the psychological test results before and one year after surgery, we used the related samples Wilcoxon signed test. The differences in weight and BMI were compared using the unpaired Student's test. P-values below .05 were considered significant.

ResultsThe study included all patients who underwent VLG and completed the psychological pre- and postoperative tests (at one year). We studied a total of 46 patients, of whom 36 were women and 10 were men. Mean age was 37 years. Initial mean BMI was 43±5, and at 12 months it was 29±3 (P<.001). All surgeries were performed laparoscopically with no conversions or re-surgery, or readmission within 30 days. No leaks were observed. There were 2 cases of postoperative hemorrhage, successfully treated conservatively. Mean hospital stay was 2.1 days. There was no mortality.

The preliminary tests yielded very high scores in body concern (BSQ test: 110.50, where a mean for all women is normally 81.5); also high scores in the EDI-1 test, and the variable in body dissatisfaction (17.11, exceeded 16, which is the cutoff limit). There was also a significant effect on three of the scales of the SF-36: vitality, health and health change, with scores of 49.35, 53.37 and 38.59 respectively (on a scale of 0–100).

Regarding the completed questionnaires 12 months later, an improvement is observed in all the analyzed scales, except perfectionism.

Examining the 12-month results in detail, we observed the most remarkable change in the variables that refer to eating disorders (assessed by EDI-1), with statistically significant improvement (P<.01) in bulimia, body dissatisfaction, ineffectiveness, obsession with thinness and introspective awareness (Tables 3 and 4). In the same food area, but with a different test (BSQ), we also found a significant improvement (P<.01) in body concern (Table 5).

BSQ.

| Body concern | |

| Preoperative | 110.50 |

| After 12 months | 73.26 |

| Improvement | 37.24 |

| % | 33.70 |

| P | <.01** |

Quality of life was assessed by the SF-36 test, yielding clearly significant improvement (P<.01) in all the variables (emphasizing health, physical functioning, and vitality), except 3 variables with lower significance (P<.05): social functioning, body pain and emotional role (Tables 6–8).

QLI-SP.

| Quality of life | |

| Pre-surgery | 64.07 |

| 12 months | 80.73 |

| Improvement | 16.67 |

| % | 20.65 |

| P | <.01** |

Given the above results, we can conclude that a substantial decrease in BMI along with a virtual disappearance of eating disorder symptoms result in many of the patients experiencing major psychological changes with a great improvement in quality of life and self-perception of health. We infer that this is so because patients, in their daily lives, stop experiencing food compulsion, obsession with weight, body dissatisfaction, etc. And the physical limitations they were experiencing (low mobility, pain, difficulty falling into deep sleep, fatigue, low vitality, choking, etc.) virtually disappear. That is, psychologically, obsessions with their bodies, with food, diet, and physical fitness disappear; they are more agile and light. To this, we have to add increased self-esteem, perception of less external criticism by relatives, acquaintances and strangers. Thus, the changes experienced by patients at the time of the surgery affect most of these areas (quality of life, social relationships, eating disorders, self-esteem, and so on, to encompass most of the variables). The remarkable thing is that this study confirms the insight we have been getting over the years with patients undergoing VLG.

This fact might indicate to us the suitability of VLG with multidisciplinary follow-up as an effective protocol for treating morbidly obese patients who want to improve their quality of life, and their physical and mental health.

Comparing the preliminary results of our study, we observed that they concur with other parameters of quality of life,24,25 obsession with thinness,11 and partly with bingeing11,24,25 (since the average of the sample does not experience a high score, but a significant amount of its subjects do).

With respect to quality of life improvement, our results also agree with previous published studies on GBP, VGB, AGBL and VLG after 12 months.10,16–19,28,29 In our study, a marked improvement at the individual level (vitality, pain, physical function) is observed, yet less at the social level, as it appears in the Kozlowska Dziurowicz study at 6 months.16 This great improvement in quality of life is crucial, since this aspect is regarded as the true measure of the effectiveness of surgery.23

Moreover, the data gathered indicate a significant improvement in the psychological status of our patients, 12 months after the surgery. The strong decrease of bulimic symptoms is significant, with very positive development of other psychological aspects related to eating disorders.

These results agree with those obtained in GBP studies and their changes after 2 years2,4,7,9,19,25,26 and with AGB after 6 months,37 in which compulsive behaviors decreased dramatically. Additionally, no difference in weight loss among binge and non-binge eaters was found.

In contrast, in an 18 month study with VGB,30 increased presence of compulsive food symptoms was observed.

Therefore, from this data, we can infer that in the short to medium term (up to 2 years), both VLG and GBP tend to greatly improve preoperative bulimic symptoms, but not VGB or AGB.

However, after 2 years of bariatric surgery, and once the weight maintenance period is confronted, studies suggest that food compulsion increases in GBP.4,6,8,9,17 In the same line, there are some studies suggesting that the type of binge eating is a significant predictor of weight regain and persistent morbid obesity.4,13–16,27

It is likely that patients undergoing VLG have behavior more similar to GBP than to VGB or AGB.29 We hypothesize that this may be due, among other things, to fundus resection or defunctioning, with the consequent drop in ghrelin. Interestingly, our patients who underwent VLG surgery experience parallels between gastric capacity and emotional desire to eat (when the patient has a full stomach, he/she does not want to eat more), while with techniques such as AGB or VGB, fullness of the neo-stomach does not guarantee the disappearance of the desire to continue eating.

In our experience, this side effect occurs after some months in the vast majority of patients who underwent AGB, so that when they have filled their smaller stomach, they are not able, but do wish, to continue eating. Thus, patients end up acquiring messy habits, snacking as soon as they feel their stomach is empty, or taking high-calorie soft foods and liquids.

Contrary to the above, we found a paper showing no significant differences between VLG and AGB, with regard to quality of life and food wellness one year after surgery.28 We believe that this discrepancy may be due to the fact that we are actually measuring different types of variables.

We highlight the critical importance of a multidisciplinary team to help patients adapt to the major changes following surgery for obesity.17 And it is precisely through this multidisciplinary process that we achieve and promote a healthy lifestyle in the diversity of the patient's life aspects.14

It seems relevant to conduct further studies showing that the results of emotional and quality of life improvements obtained with VLG are similar to those obtained with GBP, and better than those obtained with VGB and AGB.

Finally, it seems important to note the 2 main limitations of our study: first, the sample size, and second, the short-term follow-up. Thus, studies are needed with a larger sample and for a longer term (5–10 years), since we have observed some patients failing to maintain their weight over time. Furthermore, we can gain from the detailed analysis more precise information about the effectiveness of our technique and the variables that may influence therapeutic failure, in order to improve the procedure's protocols.

VLG achieves very good results in terms of improving quality of life parameters and bulimic habits, although we consider essential the postoperative work of a multidisciplinary team that focused on achieving a good emotional relationship with food, enhancing control over it, and improving one's lifestyle.

Conflict of InterestWe, the authors, state that we are not receiving or have received any external funding for our research. Furthermore, there is no potential conflict of interest referring to this paper.

The authors thank the Obésitas Clinic team, their patients and the Cirugía Española editorial team for the opportunity to publish this paper.

Please cite this article as: Melero Y, Ferrer JV, Sanahuja Á, Amador L, Hernando D. Evolución psicológica de los pacientes afectos de obesidad mórbida intervenidos mediante una gastrectomía tubular. Cir Esp. 2014;92(6):404–409.