Hospital personnel are a group which has an influence on the opinion of the rest of the population about healthcare matters. Any unfavorable attitude of this group would be an obstacle to an increase in organ donation.

ObjectiveTo analyze the attitude of hospital workers toward the donation of one's own organs in Spanish and Latin American hospitals and to determine the factors affecting this attitude.

Materials and methodsEleven hospitals from the “International Collaborative Donor Project” were selected, 3 in Spain, 5 in Mexico, 2 in Cuba and one in Costa Rica. A random sample was stratified by the type of service and job category. Attitude toward donation and transplantation was assessed using a validated survey. The questionnaire was completed anonymously and was self-administered. Statistical analysis: Student's t-test, the χ2 test and logistic regression analysis.

ResultsOf the 2785 workers surveyed, 822 were from Spain, 1595 from Mexico, 202 from Cuba and 166 from Costa Rica and 79% (n=2191) were in favor of deceased organ donation. According to country, 94% (n=189) of Cubans were in favor, compared to 82% (n=1313) of the Mexicans, 73% (n=121) of the Costa Ricans and 69% (n=568) of the Spanish (P<.001).

In the multivariate analysis, the following variables had the most specific weight: (1) originating from Cuba (odds ratio=8.196; P<.001); (2) being a physician (OR=2.544; P<.001); (3) performing a job related to transplantation (OR=1.610; P=.005); (4) having discussed the subject of donation and transplantation within the family (OR=3.690; P<.001); (5) having a partner with a favorable attitude toward donation and transplantation (OR=3.289; P<.001); (6) a respondent's belief that his or her religion is in favor of donation and transplantation (OR=3.021; P=.001); (7) not being concerned about the possible mutilation of the body after donation (OR=2.994; P<.001); (8) the preference for other options apart from burial for treating the body after death (OR=2.770; P<.001); and (9) acceptance of carrying out an autopsy if one were needed (OR=2.808; P<.001).

ConclusionsHospital personnel in Spanish and Latin American healthcare centers had a favorable attitude toward donation, although 21% of respondents were not in favor of donating. This attitude was more favorable among Latin American workers and was very much conditioned by job-related and psychosocial factors.

Los profesionales hospitalarios son un colectivo generador de opinión para el resto de la población en temas sanitarios. La actitud no favorable de dicho grupo es un obstáculo hacia el incremento de las tasas de donación de órganos propios de cadáver.

ObjetivoAnalizar la actitud de los profesionales hospitalarios hacia la donación de los órganos propios en centros sanitarios españoles y latinoamericanos y determinar los factores que condicionan dicha actitud.

Material y métodoDel «Proyecto Colaborativo Internacional Donante» se seleccionaron 11 centros hospitalarios, 3 de España, 5 de México, 2 de Cuba y uno de Costa Rica. Muestra aleatorizada y estratificada por tipo de servicio y categoría laboral. La actitud hacia la donación y el trasplante se valoró mediante una encuesta validada. El cuestionario fue anónimo y autoadministrado. Estadística: tests de la t de Student, de la χ2 y análisis de regresión logística.

ResultadosDe los 2.785 profesionales encuestados, 822 son de España, 1.595 de México, 202 de Cuba y 166 de Costa Rica. El 79% (n=2.191) está a favor de la donación de órganos de cadáver. Por país, están a favor el 94% (n=189) de los cubanos, el 82% (n=1.313) de los mexicanos, el 73% (n=121) de los costarricenses y el 69% (n=568) de los españoles (p<0,001).

En el análisis multivariante, las variables con más peso específico son: 1) país, siendo más favorable en Cuba (odds ratio=8,196; p<0,001); 2) ser médico (OR=2544; p<0,001); 3) realizar una actividad laboral relacionada con el trasplante (OR=1610; p=0,005); 4) haber comentado a nivel familiar el tema de la donación y el trasplante (OR=3,690; p<0,001); 5) la actitud a favor hacia la donación y el trasplante de la pareja (OR=3,289; p<0,001); 6) considerar el encuestado que su religión está a favor de la donación y el trasplante (OR=3,021; p=0,001); 7) no estar preocupado por la posible mutilación del cuerpo tras la donación (OR=2994; p<0,001); 8) la preferencia de otras opciones distintas de la inhumación en el tratamiento del cuerpo tras el éxitus (OR=2,770; p<0,001) y 9) la aceptación de la realización de una autopsia si fuese necesaria (OR=2,808; p<0,001).

ConclusionesLa actitud hacia la donación entre el personal hospitalario de centros sanitarios españoles y latinoamericanos es favorable, aunque un 21% no está a favor de donar. Dicha actitud es más favorable entre los profesionales latinoamericanos, y está muy condicionada por factores laborales y psicosociales.

Current organ donation rates for transplants are insufficient to cover the minimum needs.1 This shortage of organs is currently the leading cause of death among patients on waiting lists for transplant.1 Given that these treatments require mandatory pre-donation, actively promoting it in all health facilities is essential, and this is where the health professionals play a key role. This is another health promotion activity that professionals must adhere to, according to their code of conduct.

The donation process is multifactorial, which is influenced by various aspects. In this sense, health center professionals have a key role in its development. A negative stance of the professional can generate a negative stance within the public.2–4 Some data suggest that the percentage of professionals against or undecided on organ donation is relatively high.2,3 This is important, because the fact of working in a health center makes them an opinion generator group. Therefore, given their job title, their credibility on health issues is high among the public.5,6 Those who show a stance against it, can negatively predispose the public, particularly those people closest to them.2–4

Some of the factors influencing organ donations have been managed by various transplant coordination models and the professionalization of the transplant coordinator. However, family refusal to donate causes a loss of about 20% of potential donors in the Spanish organ donation model, which is the one that has shown greater effectiveness.7 One of the known barriers to organ donation is found among workers in health centers, as there is a percentage of those professionals who are against organ donation, and their stance could adversely affect the families of potential donors.2,3

In the Spanish-speaking world, there is little data on the subject; we could highlight the data from a Spanish transplant hospital published by our own group.3 The study emphasizes that the stance on cadaveric organ donation among transplant hospital staff is similar to that among the public. If this fact is generalized, it would be a major problem, as the need for advocacy activities for donation in these services is a priority, given the importance that the negative stance of this group may have on the stance of the public. A negative attitude of health professionals may influence not only potential donors, but also the attitude of people in their scope of influence.

The objective of this study is to analyze the attitude of hospital professionals in hospitals in Spain and Latin America (Mexico, Cuba and Costa Rica) toward donation of cadaveric organs, and determine the factors that influence this attitude.

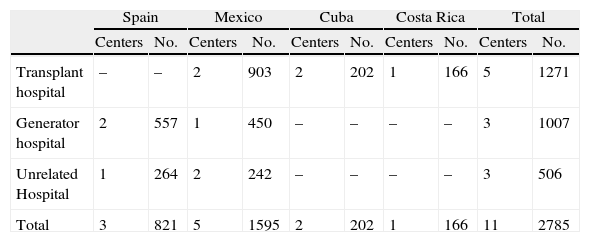

Materials and MethodsStudy PopulationSelection within the “International Collaborative Donor Project” consisted of 11 hospitals, 3 in Spain, 5 in Mexico, 2 in Cuba and one in Costa Rica. The selected centers were randomized for stratified sampling by job category (physicians, nurses, nursing assistants, and non-healthcare staff) and among various hospital departments (Table 1). The study was approved institutionally in all centers prior to inclusion in the project.

Distribution of Centers and Professionals Surveyed by Type of Health Facility and Country.

| Spain | Mexico | Cuba | Costa Rica | Total | ||||||

| Centers | No. | Centers | No. | Centers | No. | Centers | No. | Centers | No. | |

| Transplant hospital | – | – | 2 | 903 | 2 | 202 | 1 | 166 | 5 | 1271 |

| Generator hospital | 2 | 557 | 1 | 450 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 1007 |

| Unrelated Hospital | 1 | 264 | 2 | 242 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 506 |

| Total | 3 | 821 | 5 | 1595 | 2 | 202 | 1 | 166 | 11 | 2785 |

The attitude on organ donation was assessed through a survey on psychosocial aspects toward organ donation and transplant, validated in our setting (“PCID–DTO Ríos”: International Donor Collaborative Project on Organ Donation and Transplant questionnaire developed by Dr. Ríos) (α with 0.92 Cronbach).2,3,8 For the distribution of the questionnaires, each department's medical coordinator was contacted for physician questionnaires; the nurse coordinator for nurses and nursing assistants, and a member of administrative staff for non-healthcare staff; they received explanations on the study and were responsible for the distribution of the survey in selected shifts. The self-administered and anonymous questionnaire takes about 3–5min to complete.

The dependent variable under study is the stance on one's own organ donation after death. We grouped the independent variables studied into 7 categories: (1) demographic variable: country; (2) sociopersonal variables: age, sex and marital status; (3) occupational variables: type of hospital, type of clinical department where he/she works, department type as it relates to organ donation and transplant, occupational category, health staff, occupational status and transplant work-related activity; (4) variables for knowledge and stance on organ donation and transplant: personal experience with organ donation and transplant, believe in the possibility of needing a transplant for oneself in the future, know the concept of brain death; (5) variables for social interaction and prosocial behavior: attitude toward donating organs of a relative, discuss donation and transplant with family, partner's opinion on donation and transplant, and engaging in prosocial type activities; (6) religious variables: respondent's religion and knowing the respondent's religions stance on donation and transplant; (7) variables for attitudes toward the body: concern about mutilation after donation, acceptance of incineration, burial acceptance and acceptance of autopsy if necessary.

StatisticsData were stored in a database and analyzed by SPSS 15.0 statistics software. Descriptive statistics were performed, and for comparison of the different variables, we applied the Student t test and the χ2 test, followed by residue analysis. To determine and evaluate multiple risks, we performed a logistic regression analysis using the variables shown in the bivariate analysis, as having statistically significant association. In all cases, p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsStance on Donation of One's Own Solid OrgansThe questionnaire completion rate was 91% of the selected professionals. Of the 2785 respondents, 822 are from Spain, 1595 from Mexico, 202 from Cuba, and 166 from Costa Rica.

79% (n=2191) of respondents are in favor of cadaveric donation. The most frequent reasons for donating include reciprocity (58%) and solidarity (46%).

Of the 21% (n=594) of those not in favor, 6% (n=167) are against, and 15% (n=427), undecided; the most frequent reasons for not being in favor are assertive negative (just because, no reason) (33%) and fear of apparent death (31%).

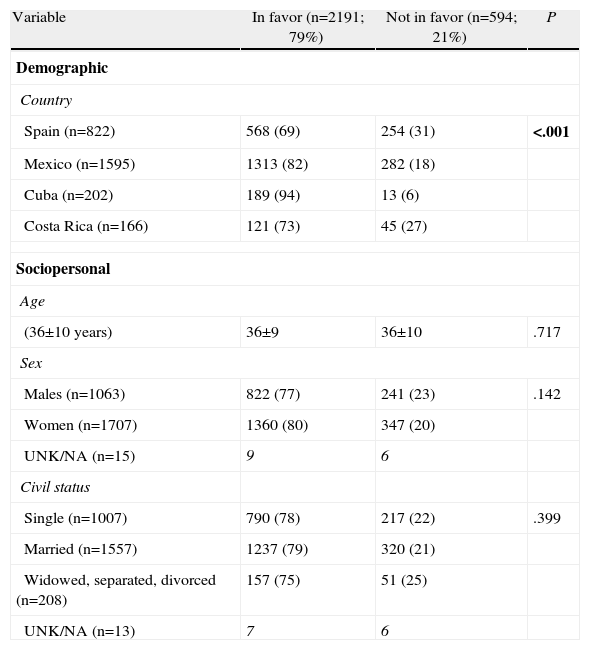

Factors Determining the Attitude on Organ DonationDemographic VariableThere is a more favorable stance among professionals in Latin American centers than among Spaniards (Table 2). Thus, in favor: 94% (n=189) of Cubans, 82% (n=1313) of Mexicans, 73% (n=121) of Costa Ricans and 69% (n=568) of Spaniards (P<.001).

Demographic and Socio-personal Variables that Influence Attitudes Toward Cadaveric Organ Donation Among Hospital Personnel in Spain and Latin America.

| Variable | In favor (n=2191; 79%) | Not in favor (n=594; 21%) | P |

| Demographic | |||

| Country | |||

| Spain (n=822) | 568 (69) | 254 (31) | <.001 |

| Mexico (n=1595) | 1313 (82) | 282 (18) | |

| Cuba (n=202) | 189 (94) | 13 (6) | |

| Costa Rica (n=166) | 121 (73) | 45 (27) | |

| Sociopersonal | |||

| Age | |||

| (36±10 years) | 36±9 | 36±10 | .717 |

| Sex | |||

| Males (n=1063) | 822 (77) | 241 (23) | .142 |

| Women (n=1707) | 1360 (80) | 347 (20) | |

| UNK/NA (n=15) | 9 | 6 | |

| Civil status | |||

| Single (n=1007) | 790 (78) | 217 (22) | .399 |

| Married (n=1557) | 1237 (79) | 320 (21) | |

| Widowed, separated, divorced (n=208) | 157 (75) | 51 (25) | |

| UNK/NA (n=13) | 7 | 6 | |

Analyzed sociopersonal factors are not associated with the stance on donating one's own body organs (Table 2).

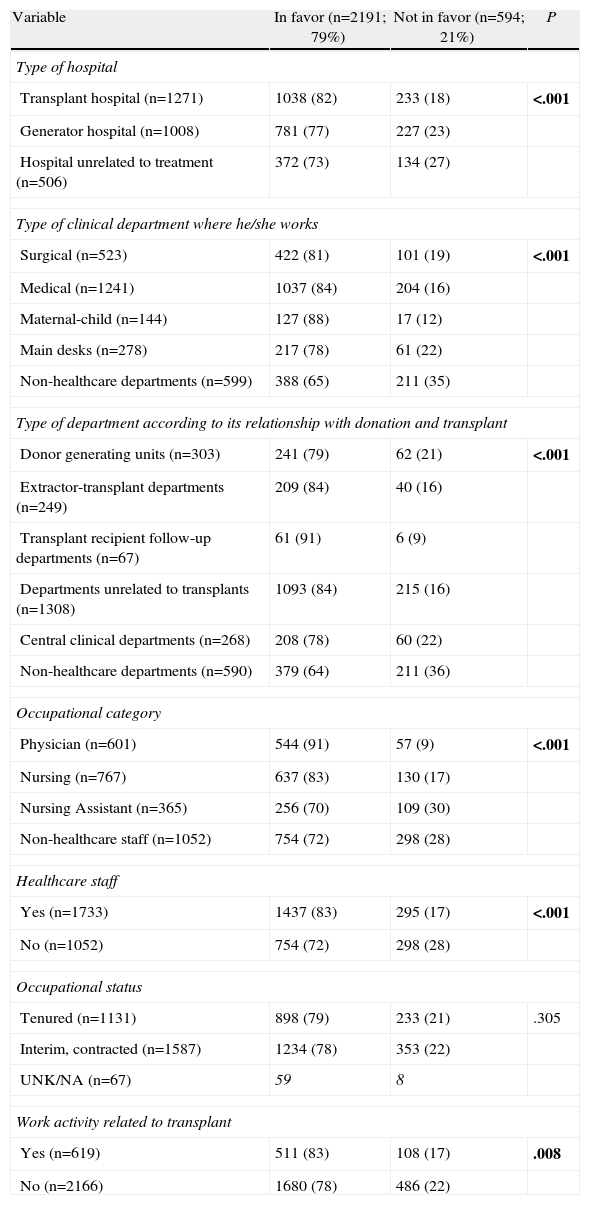

Occupational VariablesMost occupational variables show an association with the attitude on donation (Table 3). Regarding the type of hospital, professionals in transplant-related centers, both transplant surgeons and organ donor generators, have a more favorable stance than those in centers not related to transplant (82% and 77% compared to 73%) (P<.001) (Table 3). With respect to the type of department where they work, the attitude was less favorable among professionals in central departments (78% of respondents in favor) and non-health services (65% in favor) (P<.001). As for the type of service as it relates to the donation and transplant, it stresses that those working in departments that follow transplant patients are most in favor of cadaveric organ donation (91% in favor) (P<.001) (Table 3).

Occupational Variables That Influence Attitudes Toward Cadaveric Donation Among Hospital Personnel in Spain and Latin America.

| Variable | In favor (n=2191; 79%) | Not in favor (n=594; 21%) | P |

| Type of hospital | |||

| Transplant hospital (n=1271) | 1038 (82) | 233 (18) | <.001 |

| Generator hospital (n=1008) | 781 (77) | 227 (23) | |

| Hospital unrelated to treatment (n=506) | 372 (73) | 134 (27) | |

| Type of clinical department where he/she works | |||

| Surgical (n=523) | 422 (81) | 101 (19) | <.001 |

| Medical (n=1241) | 1037 (84) | 204 (16) | |

| Maternal-child (n=144) | 127 (88) | 17 (12) | |

| Main desks (n=278) | 217 (78) | 61 (22) | |

| Non-healthcare departments (n=599) | 388 (65) | 211 (35) | |

| Type of department according to its relationship with donation and transplant | |||

| Donor generating units (n=303) | 241 (79) | 62 (21) | <.001 |

| Extractor-transplant departments (n=249) | 209 (84) | 40 (16) | |

| Transplant recipient follow-up departments (n=67) | 61 (91) | 6 (9) | |

| Departments unrelated to transplants (n=1308) | 1093 (84) | 215 (16) | |

| Central clinical departments (n=268) | 208 (78) | 60 (22) | |

| Non-healthcare departments (n=590) | 379 (64) | 211 (36) | |

| Occupational category | |||

| Physician (n=601) | 544 (91) | 57 (9) | <.001 |

| Nursing (n=767) | 637 (83) | 130 (17) | |

| Nursing Assistant (n=365) | 256 (70) | 109 (30) | |

| Non-healthcare staff (n=1052) | 754 (72) | 298 (28) | |

| Healthcare staff | |||

| Yes (n=1733) | 1437 (83) | 295 (17) | <.001 |

| No (n=1052) | 754 (72) | 298 (28) | |

| Occupational status | |||

| Tenured (n=1131) | 898 (79) | 233 (21) | .305 |

| Interim, contracted (n=1587) | 1234 (78) | 353 (22) | |

| UNK/NA (n=67) | 59 | 8 | |

| Work activity related to transplant | |||

| Yes (n=619) | 511 (83) | 108 (17) | .008 |

| No (n=2166) | 1680 (78) | 486 (22) | |

NA: no answer; UNK: unknown.

Bold: statistical significance.

Italic: missing data.

Regarding occupational status, professionals with medical training are more in favor of cadaveric organ donation than those without such training. Thus, doctors and nurses have a better acceptance of donations than nursing assistants and non-medical personnel (91% and 83% in favor, compared to 70% and 72%, respectively) (P<.001). These differences are maintained if staff is classified for analysis by being healthcare related or otherwise; healthcare workers are more in favor of donation than non-healthcare workers (83% compared to 72%) (P<.001). Working in a department related to organ donation-transplant is also associated with the stance on donation (83% compared to 78%) (P=.008) (Table 3).

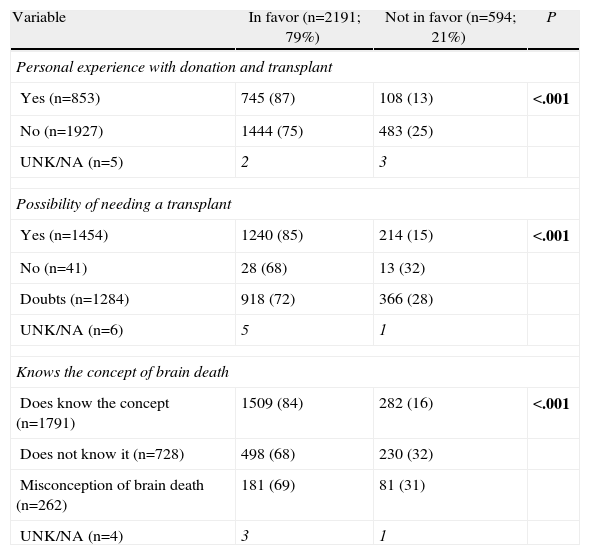

Knowledge Variables and Attitude Toward Organ Donation and TransplantHaving had personal experience with donation and transplant (knowing an organ donor or recipient among friends or family) favors the acceptance of organ donation compared with those who have none (87% compared to 75%) (P<.001) (Table 4). Those who consider the possibility of needing a transplant in the future if needed are more in favor of cadaveric donation than those who do not consider this option (85% compared to 68%) (P<.001). Knowing the brain death concept favors the stance on cadaveric donation, especially when compared to those who have a misconception or are not aware of it (84% compared to 68%) (P<.001) (Table 4).

Knowledge and Attitude Variables on Organ Donation and Transplant That Influence Stance on Cadaveric Donation Among Hospital Staff in Spain and Latin America.

| Variable | In favor (n=2191; 79%) | Not in favor (n=594; 21%) | P |

| Personal experience with donation and transplant | |||

| Yes (n=853) | 745 (87) | 108 (13) | <.001 |

| No (n=1927) | 1444 (75) | 483 (25) | |

| UNK/NA (n=5) | 2 | 3 | |

| Possibility of needing a transplant | |||

| Yes (n=1454) | 1240 (85) | 214 (15) | <.001 |

| No (n=41) | 28 (68) | 13 (32) | |

| Doubts (n=1284) | 918 (72) | 366 (28) | |

| UNK/NA (n=6) | 5 | 1 | |

| Knows the concept of brain death | |||

| Does know the concept (n=1791) | 1509 (84) | 282 (16) | <.001 |

| Does not know it (n=728) | 498 (68) | 230 (32) | |

| Misconception of brain death (n=262) | 181 (69) | 81 (31) | |

| UNK/NA (n=4) | 3 | 1 | |

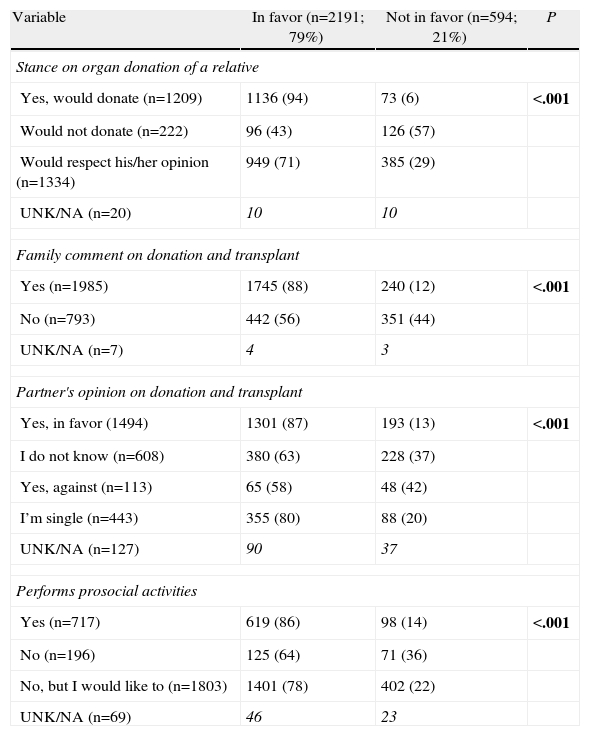

It is noted that people who would agree to organ donation of a relative are more supportive than those who would not donate them (94% compared to 43%) (P<.001) (Table 5). Having discussed the donation and transplant issue with family promotes a positive stance (88% compared to 56%) (P<.001), as well as having a partner with a stance in favor of organ donation and transplant (87% compared to 58%) (P<.001). Regarding prosocial behavior variables, people performing altruistic activities have a more favorable attitude compared with those who do not (86% compared to 64%) (P<.001) (Table 5).

Social Interaction and Prosocial Behavior Variables That Influence Attitudes Toward Cadaveric Donation Among Hospital Staff in Spain and Latin America.

| Variable | In favor (n=2191; 79%) | Not in favor (n=594; 21%) | P |

| Stance on organ donation of a relative | |||

| Yes, would donate (n=1209) | 1136 (94) | 73 (6) | <.001 |

| Would not donate (n=222) | 96 (43) | 126 (57) | |

| Would respect his/her opinion (n=1334) | 949 (71) | 385 (29) | |

| UNK/NA (n=20) | 10 | 10 | |

| Family comment on donation and transplant | |||

| Yes (n=1985) | 1745 (88) | 240 (12) | <.001 |

| No (n=793) | 442 (56) | 351 (44) | |

| UNK/NA (n=7) | 4 | 3 | |

| Partner's opinion on donation and transplant | |||

| Yes, in favor (1494) | 1301 (87) | 193 (13) | <.001 |

| I do not know (n=608) | 380 (63) | 228 (37) | |

| Yes, against (n=113) | 65 (58) | 48 (42) | |

| I’m single (n=443) | 355 (80) | 88 (20) | |

| UNK/NA (n=127) | 90 | 37 | |

| Performs prosocial activities | |||

| Yes (n=717) | 619 (86) | 98 (14) | <.001 |

| No (n=196) | 125 (64) | 71 (36) | |

| No, but I would like to (n=1803) | 1401 (78) | 402 (22) | |

| UNK/NA (n=69) | 46 | 23 | |

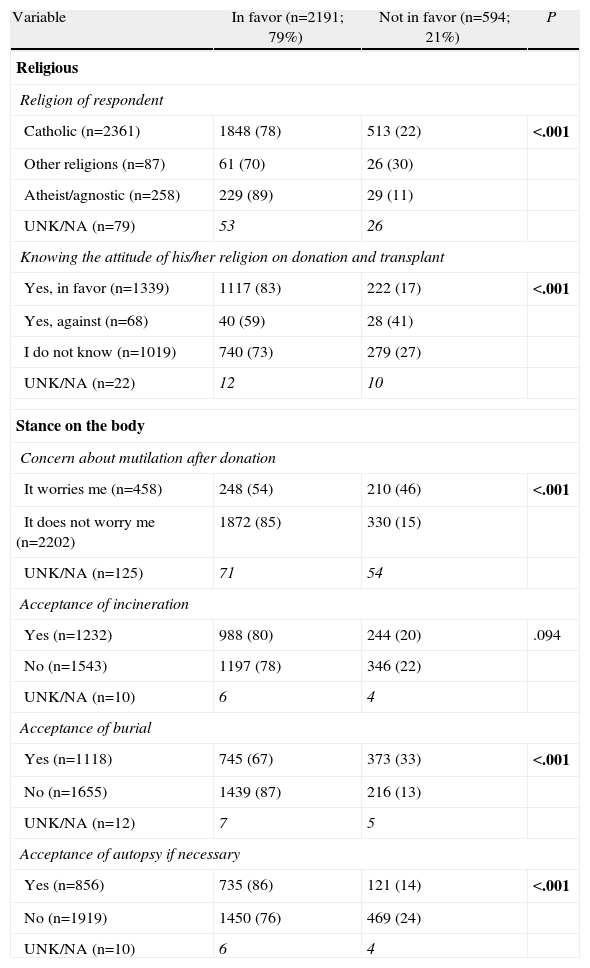

Atheists and agnostics are the respondents who are more in favor of organ donation (89%), followed by Catholics (78%), and finally, those who list other religions (70%) (P<.001) (Table 6). For believers, those believing that their doctrine is in favor of organ donation and transplant are more in favor of donation than those who consider that their religion is against it (83% compared to 59%) (P<.001) (Table 6).

Religious Variables and Variables About the Body That Influence the Stance on Cadaveric Donation Among Hospital Staff in Spain and Latin America.

| Variable | In favor (n=2191; 79%) | Not in favor (n=594; 21%) | P |

| Religious | |||

| Religion of respondent | |||

| Catholic (n=2361) | 1848 (78) | 513 (22) | <.001 |

| Other religions (n=87) | 61 (70) | 26 (30) | |

| Atheist/agnostic (n=258) | 229 (89) | 29 (11) | |

| UNK/NA (n=79) | 53 | 26 | |

| Knowing the attitude of his/her religion on donation and transplant | |||

| Yes, in favor (n=1339) | 1117 (83) | 222 (17) | <.001 |

| Yes, against (n=68) | 40 (59) | 28 (41) | |

| I do not know (n=1019) | 740 (73) | 279 (27) | |

| UNK/NA (n=22) | 12 | 10 | |

| Stance on the body | |||

| Concern about mutilation after donation | |||

| It worries me (n=458) | 248 (54) | 210 (46) | <.001 |

| It does not worry me (n=2202) | 1872 (85) | 330 (15) | |

| UNK/NA (n=125) | 71 | 54 | |

| Acceptance of incineration | |||

| Yes (n=1232) | 988 (80) | 244 (20) | .094 |

| No (n=1543) | 1197 (78) | 346 (22) | |

| UNK/NA (n=10) | 6 | 4 | |

| Acceptance of burial | |||

| Yes (n=1118) | 745 (67) | 373 (33) | <.001 |

| No (n=1655) | 1439 (87) | 216 (13) | |

| UNK/NA (n=12) | 7 | 5 | |

| Acceptance of autopsy if necessary | |||

| Yes (n=856) | 735 (86) | 121 (14) | <.001 |

| No (n=1919) | 1450 (76) | 469 (24) | |

| UNK/NA (n=10) | 6 | 4 | |

Of the professionals surveyed, those who do not care about possible body mutilation after donation are more in favor of organ donation (85% compared to 54%) (P<.001) (Table 6). We also observed a more favorable stance among those who would not accept burial as treatment for the body after death, compared to those that would (87% compared to 67%) (P<.001). Moreover, those who would accept autopsy, if necessary, have a more positive stance on cadaveric donation (86% compared to 76%) (P<.001) (Table 6).

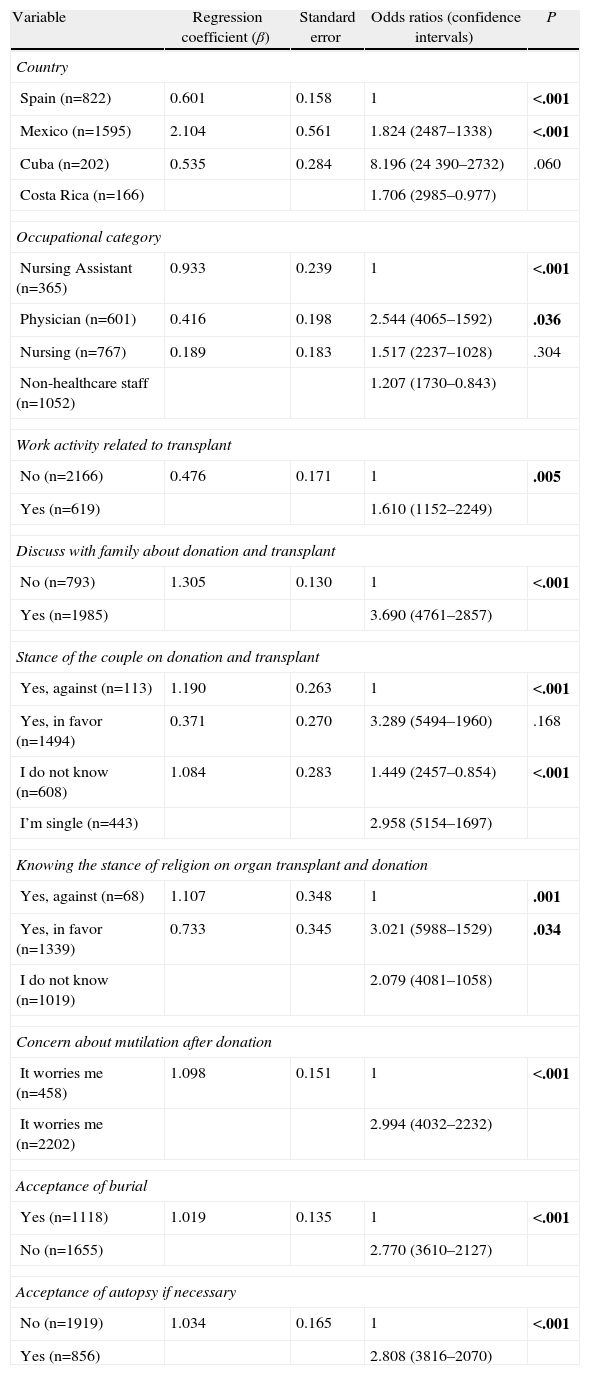

Multivariate AnalysisIn multivariate analysis, the variables with the most specific weight in the attitude toward cadaveric organ donation are (Table 7): (1) the most favorable country was Cuba (odds ratio=8.196; P<.001); (2) being a physician (odds ratio=2.544; P<.001); (3) performing work related to transplant (odds ratio=1.610; P=.005); (4) having discussed transplant and donation issues with a relative (odds ratio=3.690; P<.001); (5) the partner's favorable stance on donation and transplant (odds ratio=3.289; P<.001) or not having a partner (odds ratio=2.958; P<.001); (6) respondent considering their religion is in favor (odds ratio=3.021; P=.009) or not knowing its position (odds ratio=2.079; P=.034); (7) not worrying about body mutilation after donation (odds ratio=2.994; P<.001); (8) preferring options other than burial as a body treatment after death (odds ratio=2.770; P<.001) and (9) accepting an autopsy if necessary (odds ratio=2.808; P<.001).

Variables That Influence the Stance on Cadaveric Donation Among Spanish and Latin American Hospital Staff, Multivariate Study.

| Variable | Regression coefficient (β) | Standard error | Odds ratios (confidence intervals) | P |

| Country | ||||

| Spain (n=822) | 0.601 | 0.158 | 1 | <.001 |

| Mexico (n=1595) | 2.104 | 0.561 | 1.824 (2487–1338) | <.001 |

| Cuba (n=202) | 0.535 | 0.284 | 8.196 (24390–2732) | .060 |

| Costa Rica (n=166) | 1.706 (2985–0.977) | |||

| Occupational category | ||||

| Nursing Assistant (n=365) | 0.933 | 0.239 | 1 | <.001 |

| Physician (n=601) | 0.416 | 0.198 | 2.544 (4065–1592) | .036 |

| Nursing (n=767) | 0.189 | 0.183 | 1.517 (2237–1028) | .304 |

| Non-healthcare staff (n=1052) | 1.207 (1730–0.843) | |||

| Work activity related to transplant | ||||

| No (n=2166) | 0.476 | 0.171 | 1 | .005 |

| Yes (n=619) | 1.610 (1152–2249) | |||

| Discuss with family about donation and transplant | ||||

| No (n=793) | 1.305 | 0.130 | 1 | <.001 |

| Yes (n=1985) | 3.690 (4761–2857) | |||

| Stance of the couple on donation and transplant | ||||

| Yes, against (n=113) | 1.190 | 0.263 | 1 | <.001 |

| Yes, in favor (n=1494) | 0.371 | 0.270 | 3.289 (5494–1960) | .168 |

| I do not know (n=608) | 1.084 | 0.283 | 1.449 (2457–0.854) | <.001 |

| I’m single (n=443) | 2.958 (5154–1697) | |||

| Knowing the stance of religion on organ transplant and donation | ||||

| Yes, against (n=68) | 1.107 | 0.348 | 1 | .001 |

| Yes, in favor (n=1339) | 0.733 | 0.345 | 3.021 (5988–1529) | .034 |

| I do not know (n=1019) | 2.079 (4081–1058) | |||

| Concern about mutilation after donation | ||||

| It worries me (n=458) | 1.098 | 0.151 | 1 | <.001 |

| It worries me (n=2202) | 2.994 (4032–2232) | |||

| Acceptance of burial | ||||

| Yes (n=1118) | 1.019 | 0.135 | 1 | <.001 |

| No (n=1655) | 2.770 (3610–2127) | |||

| Acceptance of autopsy if necessary | ||||

| No (n=1919) | 1.034 | 0.165 | 1 | <.001 |

| Yes (n=856) | 2.808 (3816–2070) | |||

Solid organ transplant has become the most effective therapy and the one contributing the best quality of life to a certain group of patients with terminal dysfunction of an organ.9–12 However, developing transplant programs is hampered mainly by the shortage of available organs. This lack of organs for transplants is being fought from 2 fronts: procurement of organs from living donors13,14 and increasing the organ donation rates from deceased donors.1 Knowing the attitudes on organ donation helps to determine the factors influencing them and to develop properly designed and cost-effective campaigns. However, it is well-known that in addition to population factors of the psychosocial aspect,8,15,16 one of the barriers hindering the collection of more organs for transplant appears to be located within the healthcare structure, since a significant percentage of professionals working in a hospital can be against organ donation2,3,13,14,17 which, at a given time, can act as a barrier to donation.

Theoretically, it is known that almost all departments of a hospital end up over time having a more or less direct contact with different transplant patients, regardless of their normal activity. This more or less continuous contact with donors and recipients suggests a special awareness of the issue. However, data obtained by our group a decade ago in a Spanish transplant center showed that the rate of staff in favor of donation was only slightly higher than that described for our general population (69% compared to 64%).3,15 This information is quite surprising if, in Spain, the goal is to lower family refusal to donate by 15%–25%.1 Although these were the data from a single center, and required confirmation by studies such as this one, there were small studies conducted in another Spanish hospital which, despite their methodological limitations, pointed in the same direction.18,19 This is one of the reasons that encouraged us to conduct this study: being able to draw more general conclusions.

This study shows an entirely similar professional attitude among Spanish centers, where only 69% of professionals are in favor of organ donation. The effectiveness of the Spanish transplant coordination model overcomes this widespread limitation in Spanish centers.1 In European countries, the situation has been described as much more favorable.4,20–24 However, a more detailed analysis shows that most have a very low questionnaire completion rate, which can produce a positive bias in the sample selection, since those more in favor tend to respond more often than those against or undecided. Thus, in the Molzahn study,21 where 92% of nursing respondents are in favor, or in the Sque et al. British study,22 where 78% are in favor, completion rate is slightly above 50% for both. All these facts lead us to believe that the situation described is quite generally spread across various European countries and hospitals. For the reason discussed above, we believe that a study with a degree of completion lower than 75%–80% has no real value, because it allows many interpretations. Hence the reason that the “International Donor Collaborative Project” group does not publish studies with a low completion rate, unless there is a clear rationale as it occurred in the Spanish public study of attitudes toward live organ donation, where the low completion rate in rural areas was due to the fear of that type of donation.25 In this case, had we used those surveys, we would have had a result opposite to the real situation, i.e., the stance was very positive, when in fact it was the opposite.25

In Latin America, there is little information on the situation, given the scarcity of studies on the subject and the heterogeneity of countries. This study includes 3 countries in that geographic area, and shows great variability in the attitudes toward organ donation among professionals from one country to another. It is noteworthy that the stance is significantly more positive among professionals from Latin American countries than professionals in Spanish centers. However, these favorable attitudes are not endorsed by a proportional number of transplants performed per million inhabitants annually. This disparity between theoretical settings and reality could arise from opinions being issued without thought, without being immersed in day-to-day circumstances; therefore, poorly based on real situations, thinking more about what “would be desirable” than about what “actually is”. This same phenomenon occurs at the level of the general public, where despite there being samples showing good acceptance of donation, at the moment of truth, the data is not endorsed, with a lingering high percentage of family refusals.26 Possibly, another factor that could contribute to this phenomenon lies in the organizational model for organ procurement.1 In Latin America, although efforts are being made in many countries, including Mexico, the figure of the hospital transplant coordinator is far from being a reality, and his/her professional recognition even more so.1 This situation has stalled the launch of body donation programs despite the apparent willingness of professionals. If this enthusiastic stance among Latin American professionals is real, it could result, in the future, in a significant increase in donation rates, if the proper structural, political and economic conditions are in place. It is precisely the organizational model that has allowed Spain to achieve high rates of cadaveric donation, despite not so favorable attitudes.

It also should be noted that in Spain, donation rates are high, and this frequent contact could increase the fear of the real possibility of facing the decision to donate the organs of a family member or one's own organ donation. Conversely, in countries with lower donation rates, giving an opinion or having a stance is more theoretical.

Different psychosocial factors that influence the stance on organ donation and transplant have been described.8,15 For health professionals, there is sufficient consistency with those described for the public,2,3,15,16 while there is a group of factors that are particularly important among hospital staff. Furthermore, sociopersonal variables are not as crucial as they are for the public.8,15,16 Thus, as can be seen in Table 1, no relationship is shown for age, sex or marital status.

A group of determinants of the attitude toward organ donation corresponds to occupational factors.2,3 In this sense, the occupational category is crucial. Thus, medical staff is in favor of organ donation in over 90% of professionals surveyed. Contrarily, among nursing assistants and non-healthcare staff, only 70%–72% of respondents favor donation, which are rates superimposable to those described for the public in the Hispanic world.15 This is important because promoting organ donation and transplant is everyone's responsibility, and not just the medical staff's. Thus, if a person working in a hospital has an unfavorable attitude, he/she will create a fear of that therapeutic procedure among people who listen to him/her.2,3 This reflects our failure in part, as it implies that we are able to conduct public, school campaigns,27 etc., but otherwise, we have not been concerned about our staff being well informed and understanding what we do.

Occupational categories are closely tied to knowledge or acceptance of the brain death concept.3 Most doctors know or accept the concept; however, this knowledge decreases for people in other job categories. Therefore, understanding the concept of brain death does not appear in the multivariate analysis, because the occupational category absorbs its specific weight. We had already described this fact previously,3 but it does not seem logical, when working at a hospital, to fail to know or accept brain death as the death of a person. Moreover, this fact is reflected in the most common reason given for not being in favor of donation, which is the fear of “apparent” death. Thus, we indicate the need for further information not only about organ donation and transplant, but also about brain death, especially among non-medical groups.5,28 Some authors have already emphasized that the creation of information protocols about brain death diagnosis increases the process safety and reduces uncertainty.29–31 A negative opinion among this group communicated to the people around them is a barrier that is difficult to overcome with external campaigns. Hospital staff awareness is a fundamental aspect in the process of organ donation and transplant, and they should know that when a patient enters brain death, that patient's life prospects end, but possibilities of hope for other patients and families awaiting transplant begin.

Another important aspect of occupational variables is the workplace. Thus, the type of hospital has a direct influence on the attitude, so that hospitals performing activities related to donation and transplant (transplant hospitals and donor generator hospital) have professionals with a more favorable stance. And within these, the most favorable stance among organ donation-transplant processing units is present in transplant patient monitoring units.28,31–33 Professionals working in departments monitoring post-transplant patients are eyewitnesses to the ongoing transplant benefits on the quality of life of transplant recipients. By contrast, greater contact with the moment of death, organ removal and immediate surgical complications of transplant and generating units may result in a less favorable attitude toward donation.28,31–36

It also should be noted that in this process of stance on organ donation, factors of reciprocity clearly exert influence (“Do unto others as you would have them do to you”) and solidarity (circumstantial commitment to other people's goals).2,3,15 In this sense, these reasons are stated frequently to endorse favorable attitudes toward organ donation, and are usually correlated with the personal experience of the respondent with the donation-transplant process (having met a transplant donor and recipient), and having considered the possibility of needing a transplant for oneself. These factors have been described at the public level,8,15 and are also confirmed among healthcare center professionals.2,3

In addition to occupational factors, there are 2 main groups of factors that influence the stance on donation. First one is the influence of social and family interaction variables. In this sense, raising the issue with the family and partner highly influences the attitude toward donation. As indicated, it is essential to promote family dialog at the public level on donation and transplant issues,15 as it tends to have a positive effect.

Second factor is the influence of attitudes toward manipulating the body after death. Health professionals are no less sensitive than the general public to the feelings that arise from handling a body, and they show great difficulty to accept manipulations of the body, even for such well accepted purposes as transplants.2,3,8,15 Thus, it is very striking that up to 69% of respondents would not accept an autopsy if necessary. Theoretically, the fact of working in a health center, where contact with the process of death is commonplace, as well as the manipulation of the body, would seem to imply that it would not be such a determining factor on the stance on donation. However, it is a highly important factor, especially among non-medical personnel. Cultural and anthropological factors are closely linked to this situation and deeply rooted in the Hispanic population, and possibly will take time to change.

Finally, it is noted that for the Hispanic context and population, religious factors remain important,15 and influence the stance on the donation. Thus, only 9% of respondents consider themselves agnostics/atheists, and Catholics are the largest group among those who are religious. Campaigns promoting donation through the Catholic Church must be taken into account when considering the promotion of donation.

In conclusion, the attitude toward donation of one's own cadaveric organs among hospital staff of Spanish and Latin American medical centers is favorable, although 21% of respondents are against donation. The stance is more favorable among Latin American professionals than among Spaniards, showing discordance in the attitude of different professionals and actual donation rates in each country. Psychosocial factors that influence these attitudes are similar to those described for the Spanish-speaking public, while occupational factors, especially the job category, reflects increasing importance.

Contribution to the Authors’ StudyPlanning and design: Ríos A.

Key data acquisition: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Ayala-García MA, Sebastián MJ, García JA, Abdo-Cuza A, Alán J, Martínez-Alarcón L, Ramírez EJ, Muñoz G, Suárez-López J, Castellanos R, Ramírez R, González B, Martínez MA, Palacios G.

Data analysis and interpretation: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Ayala-García MA, Sebastián MJ, Abdo-Cuza A, Alán J, Ramírez P, Parrilla P.

Design and drafting of the paper: Ríos A.

Critical revision of the paper to improve intellectual content: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Ayala-García MA, Sebastián MJ, Abdo-Cuza A, Alán J.

Statistical analysis: Ríos A, López-Navas A.

Fundraising for the project: Ríos A.

Supervision: Ríos A, López-Navas A.

Final approval of the version to be published: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Ayala-García MA, Sebastián MJ, Abdo-Cuza A, Alán J, Martínez-Alarcón L, Ramírez EJ, Muñoz G, Suárez-López J, Castellanos R, Ramírez R, González B, Martínez MA, Ramírez P, Parrilla P.

Authors declare having no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Ayala-García MA, Sebastián MJ, Abdo-Cuza A, Alán J, et al. Estudio multicéntrico hispano-latinoamericano de actitud hacia la donación de órganos entre profesionales de centros sanitarios hospitalarios. Cir Esp. 2014;92(6):393–403.