Spontaneous dissection of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is a rare disease, with an incidence of 0.06%.1 The SMA is the most common location of isolated dissection and is the second peripheral artery in frequency after the internal carotid artery. The first case was described by Bauersfeld in 1947,2 and the review of the literature has identified only 168 cases sin then.3 It is more frequent in males (4:1) in the fifth decade of life.4 When there is suspicion of abdominal vascular compromise, CT scan is recommended as the initial diagnostic technique, while arteriography is used in patients with worsening symptoms. Anticoagulant treatment is currently the basis of conservative therapy for SMA dissection and is associated with increasingly better results.

We present the case of a 58-year-old male patient with a history of HTN, active smoking and dyslipidemia, who reported very intense abdominal pain over the previous 4h (EVA 10/10). The patient was hemodynamically stable and showed no signs of peritoneal irritation. Lab workup demonstrated leukocytosis and elevated PCR, with no metabolic acidosis.

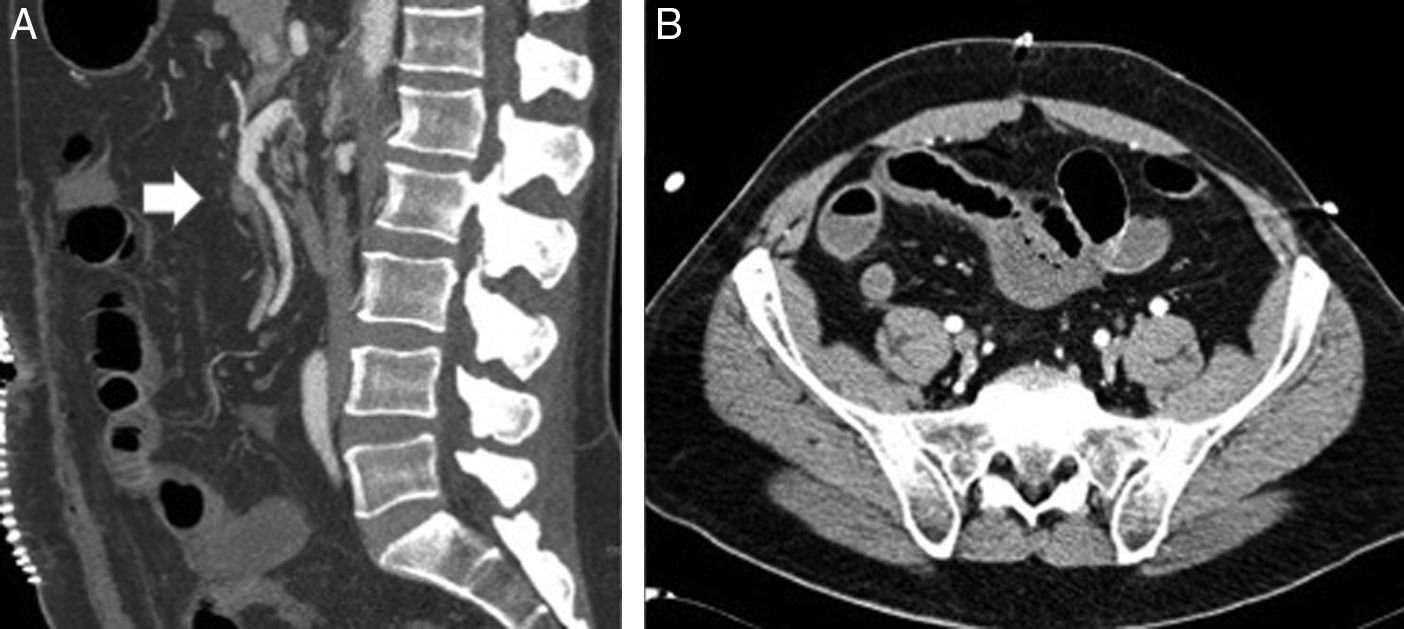

Abdominal CT scan showed a filling defect in the proximal segment of the SMA, suggestive of a thrombus that lead to stenosis of approximately 60%. There was also a linear defect inside the lumen of the vessel that extended to a jejunal branch, which may have corresponded with a flap associated with the dissection. Adequate distal filling was observed with no signs of intestinal ischemia.

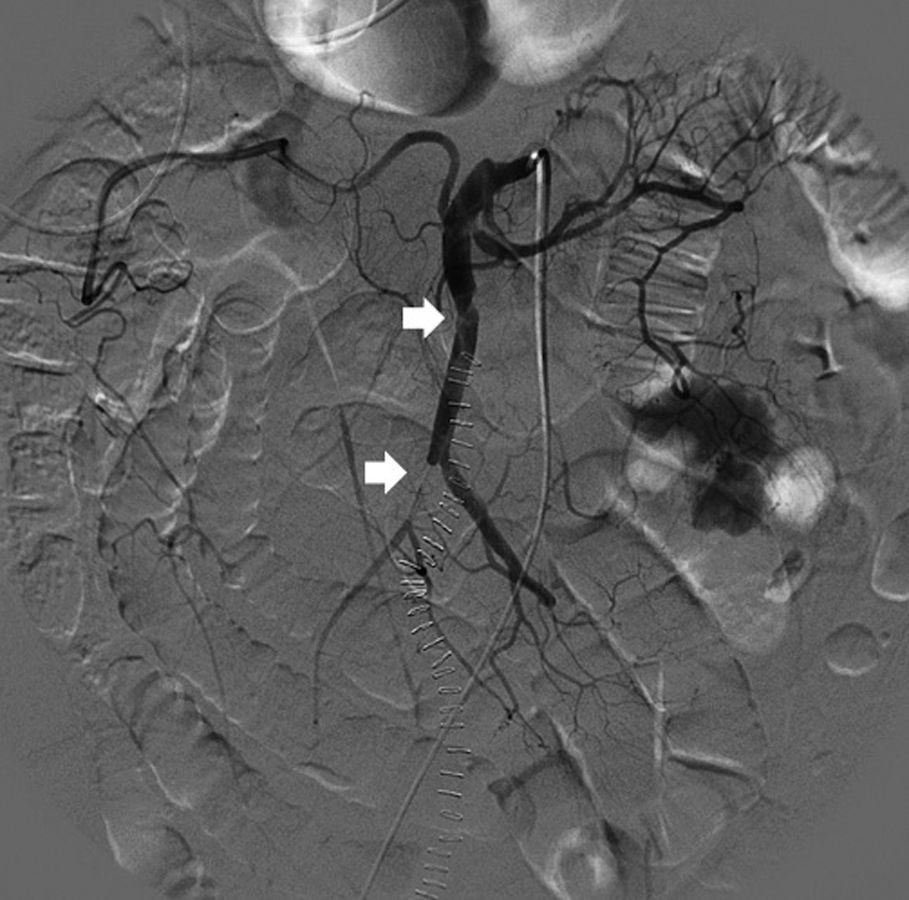

Initially, we opted for a conservative approach with anticoagulant therapy (heparin). The progression of the patient's condition became torpid, with more pain and guarding in the right hemiabdomen. The leukocytosis continued, associated with neutrophilia and mild metabolic acidosis. Given the worsening symptoms, we decided to perform CT angiography, which showed evidence of a small repletion defect at the origin of the ileocolic artery, with distal opacification related with a partially occlusive thrombus. The ileal loops located in the iliac fossa and right flank presented intestinal suffering (Fig. 1). Given the hemodynamic stability, we decided to perform a radiological approach using arteriography of the SMA, where a dissection flap was observed within the first few centimeters, causing obstruction of all the ileal branches, with no evidence of stenosis at the origin (Fig. 2).

Endovascular treatment was not considered indicated by the interventional radiology department because of the risk for aggravating the vascular obstruction.

Urgent laparotomy confirmed ischemia of the jejunum, ileum, ascending and transverse colon. Damage control surgery was performed, entailing the resection of 150cm of small intestine and extended right hemicolectomy with no anastomosis or stoma. Revision surgery 48h later involved ileocolic anastomosis in a second phase. The patient's condition progressed satisfactorily, and anticoagulation was maintained for 6 months.

The pathogenesis of spontaneous SMA dissection is uncertain, although some risk factors have been identified, such as cystic medial degeneration, fibromuscular dysplasia, connective tissue diseases, arteriosclerosis, hypertension, abdominal aortic aneurysm and trauma, although it generally occurs in previously healthy patients.5

The mean distance from the SMA ostium to the beginning of the dissection is from 1.5 to 3cm because it is a transition zone between the fixed retropancreatic proximal part of the artery and the relatively mobile more distal part that pivots with the movements of the bowel. It is at this point that an intimal flap is normally formed, which allows blood to enter the interior of the medial layer, causing a longitudinal dissection along the laminar plane of the vessel.6

The most frequent clinical presentation is acute abdominal pain due to intestinal ischemia, intraperitoneal hemorrhage due to rupture of the SMA, or the inflammatory response caused by the dissection itself, stimulating the surrounding visceral nerve plexus.

Modern imaging techniques, such as CT angiography and multidetector CT, provide visualization of the dissected artery and three-dimensional reconstructions, so they are the studies of choice in cases with clinical suspicion. Arteriography would only be indicated in patients with worsening symptoms.7,8

Anticoagulant therapy has now become the mainstay of the conservative therapy of SMA dissection as it is associated with increasingly better results. The control of HTN can reduce hemodynamic turbulences and slow down the progression of the false lumen.9

The majority of patients with incidental findings of isolated SMA dissection can be initially managed conservatively if there are no clinical or radiological signs indicating arterial rupture (such as hypovolemic shock or hemoperitoneum) or intestinal ischemia, maintaining long-term anticoagulation to prevent true thrombosis of the lumen and embolic events.

Patients who present with symptoms of hypovolemic shock or peritonitis should be treated surgically, and there are several surgical options: 1) bowel resection; 2) simple arteriotomy with thrombectomy or endarterectomy; 3) resection of the affected arterial segment with interposition of a graft; 4) re-implantation of the SMA in the aorta; and 5) bypass to the gastroepiploic artery.

The use of minimally invasive techniques, such as endovascular management with the use of percutaneous stent placement, has become increasingly common, with good clinical results. This technique, whenever technically possible, is postulated as a safe and feasible therapeutic alternative to restore blood flow to the small intestine. It is especially indicated in symptomatic patients with high perioperative risk and no signs of intestinal ischemia or hemoperitoneum, and patients should always be closely followed up.10

Please cite this article as: Abascal Amo A, Rodríguez Sánchez A, García Sanz Í, Gimeno Calvo FA, Martín Álvarez JL. Disección espontánea de arteria mesentérica superior. Cir Esp. 2018;96:54–56