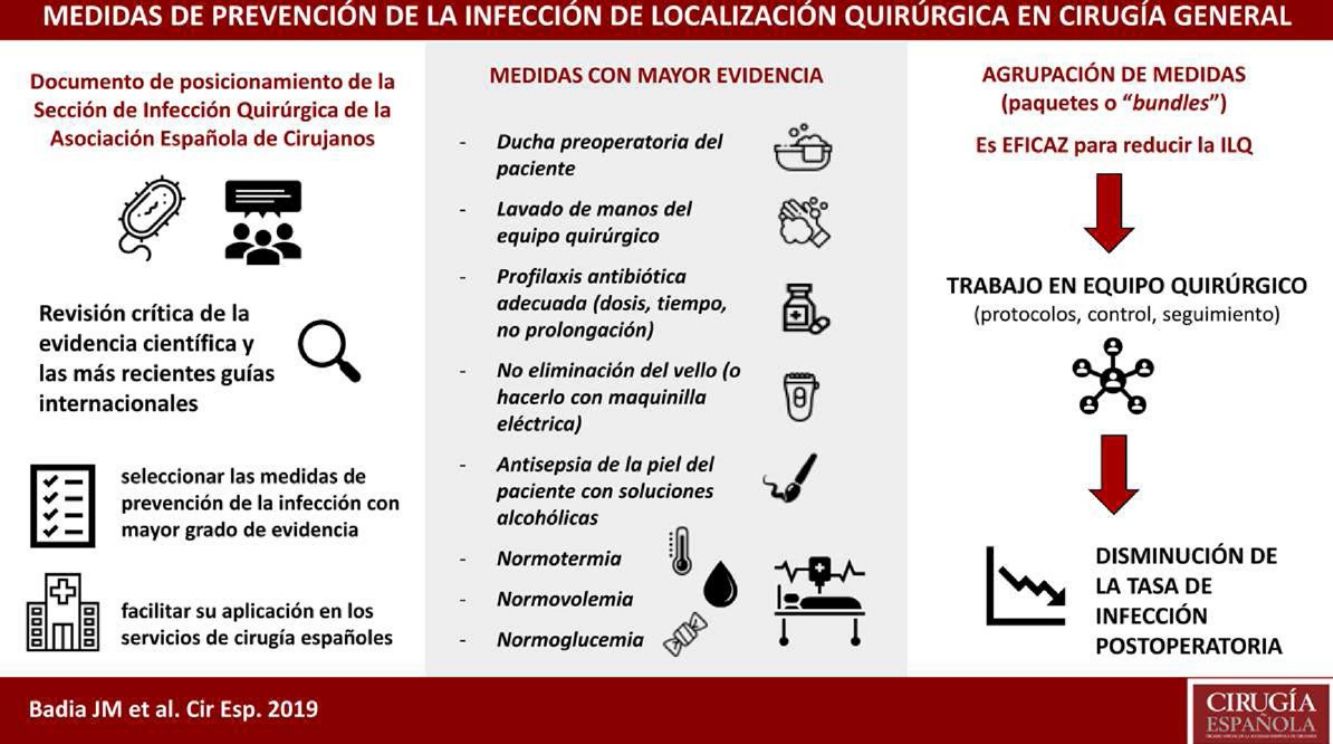

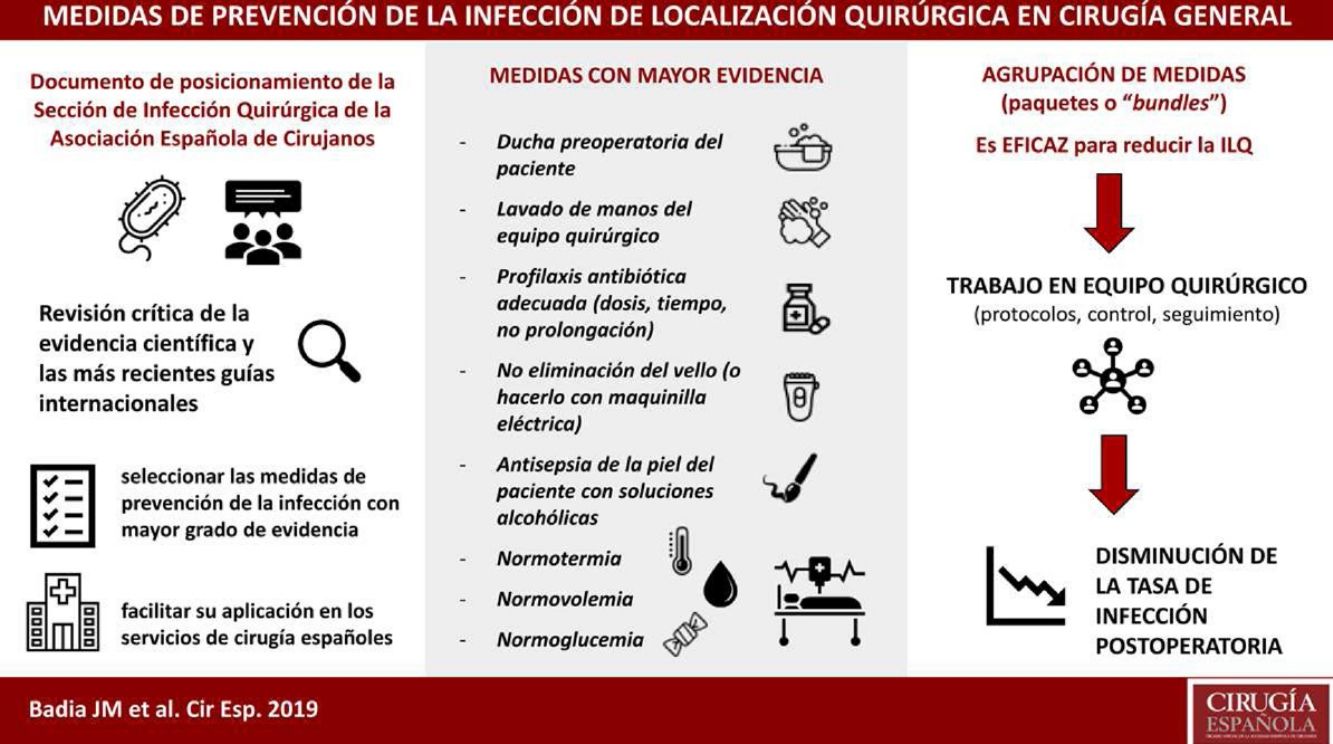

Surgical site infection is associated with prolonged hospital stay and increased morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs, as well as a poorer patient quality of life. Many hospitals have adopted scientifically-validated guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection. Most of these protocols have resulted in improved postoperative results. The Surgical Infection Division of the Spanish Association of Surgery conducted a critical review of the scientific evidence and the most recent international guidelines in order to select measures with the highest degree of evidence to be applied in Spanish surgical services. The best measures are: no removal or clipping of hair from the surgical field, skin decontamination with alcohol solutions, adequate systemic antibiotic prophylaxis (administration within 30–60min before the incision in a single preoperative dose; intraoperative re-dosing when indicated), maintenance of normothermia and perioperative maintenance of glucose levels.

La infección de localización quirúrgica se asocia a prolongación de la estancia hospitalaria, aumento de la morbilidad, mortalidad y gasto sanitario. La adherencia a paquetes sistematizados que incluyan medidas de prevención validadas científicamente consigue disminuir la tasa de infección postoperatoria. La Sección de Infección Quirúrgica de la Asociación Española de Cirujanos ha realizado una revisión crítica de la evidencia científica y las más recientes guías internacionales, para seleccionar las medidas con mayor grado de evidencia a fin de facilitar su aplicación en los servicios de cirugía españoles. Cuentan con mayor grado de evidencia: no eliminación del vello del campo quirúrgico o eliminación con maquinilla eléctrica, descontaminación de la piel con soluciones alcohólicas, profilaxis antibiótica sistémica adecuada (inicio 30-60 minutos antes de la incisión, uso preferente en monodosis, administración de dosis intraoperatoria si indicada), mantenimiento de la normotermia y el control de la glucemia perioperatoria.

Surgical site infections (SSI) are the most prevalent infections related to healthcare in Spain (21.6%)1 and in Europe (19.6%)2 and represent an important economic burden for the healthcare system, due to increased consumption of antibiotics and mean hospital stay.3

About 50% of SSI are considered avoidable, so their prevention should be a priority for scientific societies. Guidelines with prevention recommendations are published periodically, but their existence does not guarantee their use.4 The Surgical Infection Division of the Spanish Association of Surgeons has reviewed the scientific evidence to synthesize and assess the measures with the highest degree of evidence in order to facilitate their application in Spanish surgery units.

MethodsA literature review was conducted through PubMed, Tripdatabase, National Guideline Clearinghouse and The Cochrane Library. We also consulted the clinical guidelines or web pages of the World Health Organization (WHO),5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,6 National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE),7,8 Canadian Patient Safety Institute,9 Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA),10 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA),11 American College of Surgeons (ACS),12 National Health Service Scotland,13 Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality14 and Programa de Prevenció d’Infecció Quirúrgica (PREVINQ-CAT) of the Generalitat de Catalunya.15 MeSH terminology was used with keywords: postoperative complications; surgical wound infection; anastomotic leak; prevention and control; and antibiotic prophylaxis. Additional searches were performed using the terms: hair removal; skin antisepsis; decolonization; preoperative nutrition; oral antibiotic prophylaxis; mechanical colon preparation; supplemental oxygen; normothermia; normovolemia; glucose control; antiseptic sutures; wound retractor; wound irrigation; surgical site infection. The inclusion criteria were: clinical practice guidelines, controlled clinical studies, cohort studies, meta-analyses and systematic reviews. The bibliographic search, the review of the selected documents and the decision for inclusion were made by all the authors.

In this document, we have compiled and organized current recommendations for easier accessibility and consultation. In addition, the members of the Division reached a consensus, defining the most important recommendations in order of priority, adapted for actual applicability in our setting.

In the manuscript, the panel of experts issues a recommendation where there is high-quality evidence and a suggestion for moderate/low-quality evidence.

ResultsPreoperative MeasuresPreoperative NutritionMalnutrition alters healing and the response to a postoperative infection. There is confusion between optimization of nutritional status and the use of ‘immunonutrition’, which consists of specific supplements aimed at improving the immune system.

The patient should be adequately nourished before any elective procedure. WHO5 recommends immunonutrition in certain conditions (low-quality evidence). Given the inconsistent results, heterogeneity of the studies, and the high price of these preparations, more independent studies should be conducted before including them in the recommendations for SSI reduction. Immunonutrition may have a role in severely malnourished patients who will undergo major procedures (especially gastrointestinal and cardiac).16–18

Perioperative nutrition is recommended for malnourished patients. Preoperative immunonutrition is suggested in malnourished patients with cancer who are scheduled for major surgery.

Decontamination With Nasal MupirocinMupirocin nasal ointment is a safe, effective and inexpensive measure to eradicate the carrier status of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus).5

The evidence is not unanimous and focuses mainly on cardiac and orthopedic surgery.19–22 There is insufficient/low-quality evidence of nasal decontamination reducing the SSI rate in cardiac surgery.23

Systematic screening and decolonization of S. aureus carriers prior to general surgery is not recommended.

Suspension of Immunomodulatory Therapy Before SurgeryIn transplant patients or those with inflammatory diseases, systemic immunosuppressive therapy is considered a risk factor for SSI.24,25 However, its preoperative discontinuation would also carry risks, such as rejection or exacerbation of the baseline disease.26

Most studies have focused on methotrexate, biological agents (mainly anti-TNF) and corticosteroids. With a low level of evidence, it is recommended to not suspend these treatments.5,6 Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis is also not recommended in patients with immunosuppressive therapy.6

Withdrawal of systemic immunosuppressive therapy prior to major surgery is not recommended.

Preoperative Bath/showerFor disinfection of the skin before a procedure, there is little evidence on the number of baths or showers, the best time for them, or the type of soap and number of applications. The preoperative shower with chlorhexidine soap reduces the bacterial inoculum more than povidone-iodine soap or non-pharmacological soap.27,28 However, this reduction in microflora has not been correlated with a lower incidence of SSI.29–32 It has been suggested that this may be due to the heterogeneous mode of application of the soap (number of applications, length of time, how long before surgery)33 and that patients should be given precise instructions.34 It is necessary to insist on adequately washing the axillae, groin area and skin folds, and, in case of chlorhexidine soaps, wait the indicated time (1–2 min) before rinsing. All guidelines recommend a bath or shower with soap and water or with antiseptic soaps.5–15

It is recommended that patients should take a shower the day of the procedure with chlorhexidine soap or a non-pharmacological soap, and patients should be provided detailed information about the steps to follow.

Bowel PreparationBowel preparation with enemas does not reduce infectious complications or anastomotic dehiscence when used without oral antibiotics,35–41 so it can be omitted in elective colorectal surgery.

The SHEA-IDSA10 and WHO5 guidelines coincide by proposing it only if used in combination with oral antibiotics.

Preparation of the isolated colon is not recommended as a preventive measure for SSI in colorectal surgery.

Oral Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Colorectal SurgeryRandomized studies and meta-analyses have shown that oral antibiotics combined with bowel preparation reduce the risk of superficial, deep and organ/space (O/S) SSI.5,42–47 Until now, none of these studies have analyzed the effect of oral antibiotics in the absence of bowl preparation. A randomized study exclusively in colon surgery48 found no decrease in SSI comparing bowel preparation and oral antibiotic with lack of preparation. However, the study has little statistical power to detect the 4% reduction in SSI obtained by the preparation group.49 In contrast, large population-based studies have found a lower incidence of SSI and other complications.50–55 The risk of colitis due to Clostridium difficile is low.46 The effect of oral antibiotics in the absence of preparation has not been sufficiently defined, due to the lack of controlled studies and the small number of patients with this modality in population studies. The only two guidelines that address this topic recommend them in combination with bowel preparation.5,10 Current evidence does not allow us to recommend one antibiotic regimen over another (including timing and dose). Some of the most widely used are aminoglycosides in combination with anaerobicides (metronidazole or erythromycin). Gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes must be covered, and enteric non-absorbable antibiotics are preferred.

Oral antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended in association with bowel preparation for colorectal surgery.

Appropriate Antibiotic ProphylaxisAntibiotic prophylaxis is essential for the reduction of SSI in the procedures in which it is indicated. Therapeutic tissue concentrations should be achieved at the time of incision and throughout the procedure. In the case of the most widely used beta-lactams, given their volume of distribution and half-life, intravenous administration 30–60 min before the incision is considered optimal.

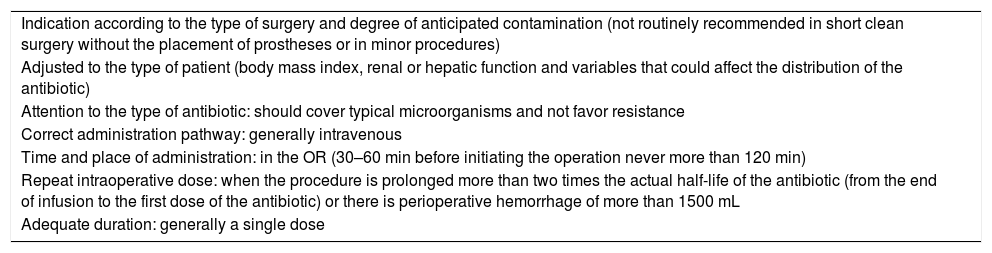

In order to consider antibiotic prophylaxis adequate, certain criteria must be met, including indication, dosage, infusion time and duration, as specified in Table 1.5–15 The WHO surgical safety checklist includes it as an element to check before starting the procedure.

Criteria for Adequate Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery.

| Indication according to the type of surgery and degree of anticipated contamination (not routinely recommended in short clean surgery without the placement of prostheses or in minor procedures) |

| Adjusted to the type of patient (body mass index, renal or hepatic function and variables that could affect the distribution of the antibiotic) |

| Attention to the type of antibiotic: should cover typical microorganisms and not favor resistance |

| Correct administration pathway: generally intravenous |

| Time and place of administration: in the OR (30–60 min before initiating the operation never more than 120 min) |

| Repeat intraoperative dose: when the procedure is prolonged more than two times the actual half-life of the antibiotic (from the end of infusion to the first dose of the antibiotic) or there is perioperative hemorrhage of more than 1500 mL |

| Adequate duration: generally a single dose |

Adequate systemic antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended, generally as a single dose. Re-dosages are recommended to provide optimal therapeutic levels throughout the procedure.

Extension of Antibiotic ProphylaxisExcessive duration is the most frequent error in the use of prophylaxis,56 and it is associated with increased toxicity, costs, and bacterial resistance. Antibiotic administration after wound closure does not decrease the risk of SSI (strong recommendation).5,10,12,57

It is recommended not to prolong antibiotic prophylaxis more than 24 h.

Hair RemovalHair can interfere with exposure of the surgical field, but its removal involves cutaneous microtrauma due to cutting, chemical abrasion or skin reactions depending on the agent used (razor blades, electric shavers or hair removal cream).12 The guidelines5–9,12,58 indicate that it is a questionable measure. The risk of SSI is comparable if the hair is not removed or if it is removed with an electric shaver with a disposable head, but it is higher with razor blades or depilatory creams.5

Routine hair removal from the surgical field is not recommended. If deemed necessary, it should be removed outside the surgical area, shortly before the start of the procedure and using an electric shaver.

Intraoperative MeasuresPreparation/hand WashingBacteria residing on the skin of the surgical team can cause SSI.59,60 The most widely used antiseptics for hand hygiene have been chlorhexidine or povidone soap solutions. Alcohols act quickly and have a broad spectrum, but their antibacterial action is neither persistent nor cumulative and must be combined with other antiseptics, such as chlorhexidine, which has a high residual effect.

In addition to hand-washing, associated measures should include no artificial nails, wearing trimmed nails, cleaning the subungual space, and removing rings and bracelets. If the hands are not visibly dirty, there is no difference between washing with 7.5%–10% povidone or 4% chlorhexidine soap solutions or applying an alcoholic solution.

An initial wash of the day is recommended, using a nail brush and an antiseptic soap solution for 5 min. If the surgeon remains in the surgery unit, successive washes between procedures can also be carried out with antiseptic soap or alcoholic solutions for 2 min (two 60-second washes, allowing to dry completely at the end of the procedure), allowing the product to evaporate.5,61

It is recommended that the first surgical hand hygiene of the day be for 5 min with antiseptic soap solution, including hands, forearms and elbows.

Subsequent surgical preparations can be with antiseptic soap or alcohol solutions, allowing it to evaporate from the skin.

Antisepsis of the SkinAntisepsis in the surgical field reduces the incidence of SSI.5,10 Chlorhexidine solutions seem more effective than povidone-iodine solutions in clean or clean-contaminated surgery.5,62–64 Alcohol solutions, which add two antiseptics, are more effective than aqueous ones.5,6 A 2% chlorhexidine alcohol solution has a greater effect than 1% povidone iodine (low or moderate-quality evidence).65–68

Alcohol-based preparations cannot be used on mucous membranes, nerve tissue, damaged skin or in newborns, where aqueous solutions of chlorhexidine or povidone are recommended. There is a risk of ignition when alcohol solutions are used in combination with the electric scalpel,69 so it is necessary to minimize the amount that is applied, avoid spillage on the surgical drapes, and allow to air-dry a minimum of three min before placing the surgical drape. Due to the possibility of contamination of antiseptic containers, single-dose bottles are recommended. Drug-grade antiseptics are more reliable than biocides. Sterile single-dose applicators can increase the safety of using alcoholic solutions.

On undamaged skin, it is recommended to disinfect the skin with an alcohol solution of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate with 70% alcohol or 5% povidone-iodine in 70% alcohol, using an adequate quantity and extension.

On mucosa or skin with open wounds, a water-based antiseptic with 2% chlorhexidine or 10% povidone iodine is recommended.

It is recommended that all antiseptics should be allowed to act on the skin for at least 3 min and then air dry completely before placing the surgical drape.

When alcohol solutions are used, strict safety measures are recommended to avoid the risk of fire and burns.

Surgical Gowns/surgical DrapesSterile drapes and gowns minimize contamination, but they lose their function if they get wet. The WHO suggests that non-reusable and reusable drapes and gowns are equivalent (conditional recommendation, moderate-very low quality of evidence).5 The cost, protection and comfort factors are reasonably similar, but disposable materials present sustainability problems (waste of natural resources and water, carbon footprint and solid waste).70

There is little evidence about the clothing of surgical staff. The Joint Commission and ACS support the following: the use of disposable surgical caps and covering the mouth, nose, and head hair during all invasive procedures; surgical masks are not to be untied and hanging; a surgical cap that covers the hair, with removal or coverage of head and neck jewelry; leaving the surgical area in a different outfit than the one used in it; and never going out in the same clothing outside the hospital perimeter.

The use of masks and caps to cover the hair are recommended, as well as sterile surgical drapes and surgical clothing.

It is not recommended to wear the surgical clothing outside the surgery unit.

Adhesive Plastic Protectors on the Surgical FieldAdhesive clear plastics placed over the surgical field71 increase SSI and are not currently recommended.72 There are adhesive plastics impregnated with antimicrobial substances, usually iodophors, which also do not provide a clear benefit.73–76 However, the NICE recommendations indicate that iodophors plastics can be used if necessary to affix the drapes.7

It is not recommended to use adhesive plastic protectors on the surgical field.

Use of Skin SealantsSealants are chemical substances that form a protective film on the skin with the intention of acting as a barrier and blocking the passage of bacteria to the wound. The evidence in their favor is low quality and shows no benefit.5 Sealants are not routinely used in our setting. With the available evidence, their use would not be justified in a public health system due to a cost-benefit issue.

It is not recommended to use skin sealants on the surgical field.

Protection of Surgical Wound MarginsThe application of waterproof physical barriers at the edges of the wound significantly reduces the rate of SSI.77,78 In laparotomy, single-ring plastic devices do not offer significant protection, while double-ring devices seem to significantly decrease the risk of infection.5,79–81

The use of plastic protectors is recommended to protect the margins of the surgical wound, preferably double-ring.

NormoglycemiaPerioperative hyperglycemia is associated with increased SSI. For its prevention, non-strict glycemic control must be established, both in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. During the intraoperative phase and in the immediate postoperative period, the objective is to treat hyperglycemia with rapid insulin to maintain levels around 150–200 mg/dL (8.3–11.1 mmoL/L). Strict control, with values <150 mg/dL, can be detrimental due to the high percentage of hypoglycemia.5–7,15

Non-strict control of perioperative blood glucose is recommended in major surgery in diabetic and non-diabetic patients, with the aim of reaching levels below 150–200 mg/dL (8.3–11.1 mmoL/L).

NormovolemiaThe current recommendation is based on goal-directed fluid therapy to avoid systemic and local hemodynamic deficit in the surgical space.5 A correlation has been observed between the time of intraoperative hypotension and the rate of SSI,82 as well as with compromised vascularization and oxygenation of intestinal anastomoses.83,84

It is recommended to avoid perioperative hypotension and excess volume, which produces tissue edema and a significant expansion of extracellular volume. These situations can interfere both in the correct healing of anastomoses and sutures and in the correct bioavailability of prophylactic antibiotics.

NormothermiaPerioperative hypothermia is associated with a higher SSI rate and more blood loss. There is no consensus on the best method for temperature measurement (core temperature using the esophageal probe may be the most reliable) or on the method for heating (pressurized hot air, fluid heating systems, thermal mats) in patients with complex surgical fields.5–15

It is recommended to keep the patient's core temperature above 36°C during the entire perioperative period in all procedures >30 min.

OxygenationPerioperative hyperoxygenation, with an increase in the inspired oxygen fraction (FiO2) of 80% in patients undergoing general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation, has been proposed as a measure to improve the healing of gastrointestinal anastomoses and the local perioperative inflammatory response, while decreasing SSI.5 High perioperative oxygen concentrations do not appear to be harmful, but clinical results are conflicting.85,86 The initial WHO recommendations were controversial and have generated new meta-analyses that have reconsidered the recommendation.87

Hyperoxia is not recommended during the perioperative period.

Ventilation Systems With Laminar Flow in the Operating RoomThe existence of germs in sufficient concentration in the operating room environment can lead to the appearance of SSI. Some studies show a reduction in the concentration of germs in the operating room with laminar flow systems,88 although with an uncertain impact on the rate of SSI.89 The literature offers contradictory results.90–92 Laminar flow ventilation systems do not provide a sufficient clinical benefits to justify the expense of their installation.5

The installation of laminar flow ventilation systems in general surgery operating rooms is not recommended.

Use of Double Surgical GloveThe use of gloves protects healthcare personnel from body fluids and reduces the transmission of microorganisms from the hands of staff.93 The use of double gloves decreases the perforation rate of the inner glove,94 but there is no direct evidence that glove defects increase the risk of SSI.95

Despite this, the ACS, SHEA and IDSA guidelines recommend the routine use of double gloves.10,12 The WHO does not find sufficient evidence to evaluate its effectiveness or the criteria for changing gloves during the operation or the types of gloves.5 NICE recommends the use of double gloves if there is a high risk of perforation and a risk for personnel.7,8

The use of double gloves is suggested to increase protection against contamination both from patients to the surgical team and from the surgical team to patients.

Sutures With AntisepticAntiseptic-coated sutures reduce in vitro bacterial colonization. There is controversy over their usefulness in vivo, and meta-analyses have provided conflicting results.96–98 In general, the studies have a high possibility of bias, are low in quality and have potential conflicts of interest. The most recent meta-analysis show has shown a reduction in the incidence of SSI with sutures impregnated with triclosan.99 However, the benefit was only evident with polyglactin 910 sutures and not polydioxanone sutures. The effect seems to be independent of the type of surgery performed and the level of contamination, although in high-quality studies the effect is only maintained in clean surgery.

NICE, CDC and WHO suggest considering their use in all types of procedures.5,6,8 The WHO considers it necessary to carry out more studies, analyze other types of antiseptics and consider variables such as availability and costs, depending on the field in which these sutures are being used.

The use of sutures impregnated with antiseptic is suggested in clean and clean-contaminated surgery.

Irrigation of the Surgical WoundThe irrigation of the wound at the end of the procedure aims to reduce the bacterial load, detritus and foreign bodies. Various studies have analyzed irrigation with saline, antiseptic and antibiotic solutions with inconclusive results. Meta-analyses show great heterogeneity and low quality of studies. Their conclusions are contradictory, especially in antibiotic and antiseptic solutions, which imply possible toxicity and a potential increase in bacterial resistance to the drugs used.

In a meta-analysis,100 irrigation with any solution was superior to the absence of washing. Subgroup analyses showed significance in colorectal surgery, as well as a greater effect of antibiotic solutions versus povidone. Another meta-analysis101 showed that irrigation with pressurized saline reduces SSI and that the aqueous povidone-iodine solution could be beneficial, particularly in clean and clean-contaminated surgery (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence). Antibiotic irrigation would not prevent SSI (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence). In 2019, new meta-analyses did not recommend irrigation with povidone-iodine,102 but they found that irrigation with beta-lactam antibiotics could be effective.103 However, due to the quality of the studies, the efficacy of antibiotic washing cannot be confirmed our ruled out.

Irrigation of the surgical wound could have a beneficial effect on SSI by removing debris, clots and potentially decreasing the bacterial inoculum after contaminated surgery. However, due to the great heterogeneity of the trials, no specific regimen can be recommended at this time.

Wound irrigation is suggested at the end of the procedure with a moderate amount of a pressurized solution to remove detritus and foreign bodies.

Change of Surgical MaterialSurgical instruments can become contaminated during surgery (by contact with the skin microbiota or bacteria from the digestive tract). There have been no controlled studies about changing the surgical material before the closure of the abdominal wall.5 However, it seems obvious that the material should be changed when moving from a dirty or contaminated area to a clean area.104 The average biological load in contaminated procedures is 5 times higher than in clean-contaminated procedures.105–110

It is suggested to change the surgical instruments and the auxiliary material (aspiration tips, electric scalpel, surgical lamp cover) before the closure of the wounds in clean-contaminated, contaminated and dirty surgery.

Glove ChangesThere is little evidence about the changes of gloves and gowns at the end of a procedure, and the most recent comes from the analysis of bundles that include them in their list of measures.111,112 It is advisable to change gloves when contamination or perforation is suspected and when a contaminated surgical stage is over, such as an anastomosis.

Glove changes are suggested when contamination or perforation is suspected, at the end of a gastrointestinal anastomosis and, as a routine, in operations of more than 2 hours, before placing a prosthesis and before closing the incision.

Postoperative MeasuresProtective Dressings for Surgical WoundsThe surgical wound should be protected with a sterile dressing for 24–48 h. Staff should wash their hands before and after any contact with the surgical wound or dressing change, and glue should not be used on the wounds after surgery.5,7,8,15 There is not enough evidence to advise one type of active dressing over others. Unnecessary manipulation of wounds should be avoided in the postoperative period.

It is recommended to apply a dressing with sterile gauze for 48 h on surgical wounds.

Negative Pressure TherapyNegative pressure wound therapy applies a sealed system connected to a vacuum pump on a primary wound closure. In abdominal and cardiac surgery, a reduction of SSI is achieved with the application of these systems compared to conventional dressings. The WHO recommends their use in surgeries with a high risk of infection (great tissue damage, ischemia, dead spaces, hematoma or great intraoperative contamination).5 The Surgical Infection Society (SIS) limits its recommendation to open abdominal surgery or vascular surgery in the groin.12 Given the current high cost of this measure, it should be limited to high-risk SSI surgery, and whenever available.

Negative pressure therapy on the closed wound is suggested only in surgery with a high risk of infection.

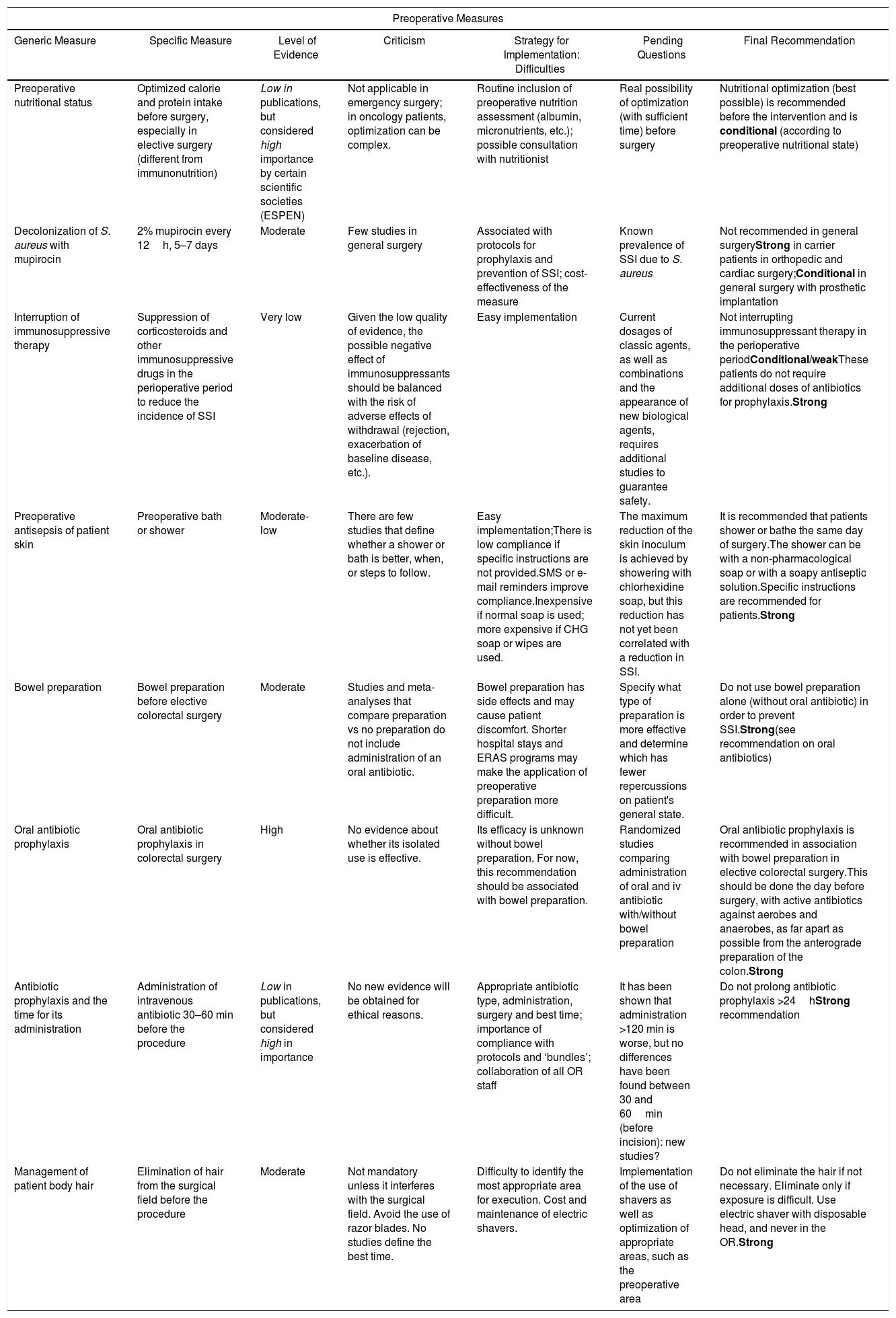

Preoperative SSI prevention measures are summarized in Table 2, and intra- and postoperative measures in Table 3. The complete list of measures and recommendations is shown in Appendix B.

Preoperative Measures.

| Preoperative Measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Measure | Specific Measure | Level of Evidence | Criticism | Strategy for Implementation: Difficulties | Pending Questions | Final Recommendation |

| Preoperative nutritional status | Optimized calorie and protein intake before surgery, especially in elective surgery (different from immunonutrition) | Low in publications, but considered high importance by certain scientific societies (ESPEN) | Not applicable in emergency surgery; in oncology patients, optimization can be complex. | Routine inclusion of preoperative nutrition assessment (albumin, micronutrients, etc.); possible consultation with nutritionist | Real possibility of optimization (with sufficient time) before surgery | Nutritional optimization (best possible) is recommended before the intervention and is conditional (according to preoperative nutritional state) |

| Decolonization of S. aureus with mupirocin | 2% mupirocin every 12h, 5–7 days | Moderate | Few studies in general surgery | Associated with protocols for prophylaxis and prevention of SSI; cost-effectiveness of the measure | Known prevalence of SSI due to S. aureus | Not recommended in general surgeryStrong in carrier patients in orthopedic and cardiac surgery;Conditional in general surgery with prosthetic implantation |

| Interruption of immunosuppressive therapy | Suppression of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive drugs in the perioperative period to reduce the incidence of SSI | Very low | Given the low quality of evidence, the possible negative effect of immunosuppressants should be balanced with the risk of adverse effects of withdrawal (rejection, exacerbation of baseline disease, etc.). | Easy implementation | Current dosages of classic agents, as well as combinations and the appearance of new biological agents, requires additional studies to guarantee safety. | Not interrupting immunosuppressant therapy in the perioperative periodConditional/weakThese patients do not require additional doses of antibiotics for prophylaxis.Strong |

| Preoperative antisepsis of patient skin | Preoperative bath or shower | Moderate-low | There are few studies that define whether a shower or bath is better, when, or steps to follow. | Easy implementation;There is low compliance if specific instructions are not provided.SMS or e-mail reminders improve compliance.Inexpensive if normal soap is used; more expensive if CHG soap or wipes are used. | The maximum reduction of the skin inoculum is achieved by showering with chlorhexidine soap, but this reduction has not yet been correlated with a reduction in SSI. | It is recommended that patients shower or bathe the same day of surgery.The shower can be with a non-pharmacological soap or with a soapy antiseptic solution.Specific instructions are recommended for patients.Strong |

| Bowel preparation | Bowel preparation before elective colorectal surgery | Moderate | Studies and meta-analyses that compare preparation vs no preparation do not include administration of an oral antibiotic. | Bowel preparation has side effects and may cause patient discomfort. Shorter hospital stays and ERAS programs may make the application of preoperative preparation more difficult. | Specify what type of preparation is more effective and determine which has fewer repercussions on patient's general state. | Do not use bowel preparation alone (without oral antibiotic) in order to prevent SSI.Strong(see recommendation on oral antibiotics) |

| Oral antibiotic prophylaxis | Oral antibiotic prophylaxis in colorectal surgery | High | No evidence about whether its isolated use is effective. | Its efficacy is unknown without bowel preparation. For now, this recommendation should be associated with bowel preparation. | Randomized studies comparing administration of oral and iv antibiotic with/without bowel preparation | Oral antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended in association with bowel preparation in elective colorectal surgery.This should be done the day before surgery, with active antibiotics against aerobes and anaerobes, as far apart as possible from the anterograde preparation of the colon.Strong |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis and the time for its administration | Administration of intravenous antibiotic 30–60 min before the procedure | Low in publications, but considered high in importance | No new evidence will be obtained for ethical reasons. | Appropriate antibiotic type, administration, surgery and best time; importance of compliance with protocols and ‘bundles’; collaboration of all OR staff | It has been shown that administration >120 min is worse, but no differences have been found between 30 and 60min (before incision): new studies? | Do not prolong antibiotic prophylaxis >24hStrong recommendation |

| Management of patient body hair | Elimination of hair from the surgical field before the procedure | Moderate | Not mandatory unless it interferes with the surgical field. Avoid the use of razor blades. No studies define the best time. | Difficulty to identify the most appropriate area for execution. Cost and maintenance of electric shavers. | Implementation of the use of shavers as well as optimization of appropriate areas, such as the preoperative area | Do not eliminate the hair if not necessary. Eliminate only if exposure is difficult. Use electric shaver with disposable head, and never in the OR.Strong |

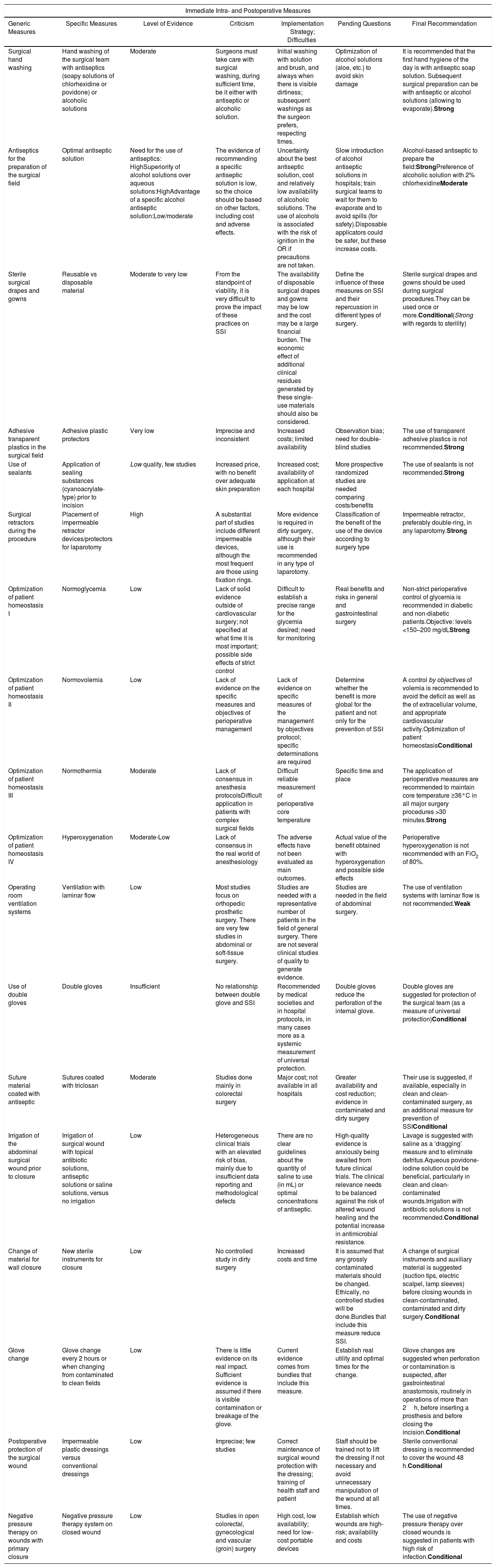

Immediate Intra- and Postoperative Measures.

| Immediate Intra- and Postoperative Measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Measures | Specific Measures | Level of Evidence | Criticism | Implementation Strategy; Difficulties | Pending Questions | Final Recommendation |

| Surgical hand washing | Hand washing of the surgical team with antiseptics (soapy solutions of chlorhexidine or povidone) or alcoholic solutions | Moderate | Surgeons must take care with surgical washing, during sufficient time, be it either with antiseptic or alcoholic solution. | Initial washing with solution and brush, and always when there is visible dirtiness; subsequent washings as the surgeon prefers, respecting times. | Optimization of alcohol solutions (aloe, etc.) to avoid skin damage | It is recommended that the first hand hygiene of the day is with antiseptic soap solution. Subsequent surgical preparation can be with antiseptic or alcohol solutions (allowing to evaporate).Strong |

| Antiseptics for the preparation of the surgical field | Optimal antiseptic solution | Need for the use of antiseptics: HighSuperiority of alcohol solutions over aqueous solutions:HighAdvantage of a specific alcohol antiseptic solution:Low/moderate | The evidence of recommending a specific antiseptic solution is low, so the choice should be based on other factors, including cost and adverse effects. | Uncertainty about the best antiseptic solution, cost and relatively low availability of alcoholic solutions. The use of alcohols is associated with the risk of ignition in the OR if precautions are not taken. | Slow introduction of alcohol antiseptic solutions in hospitals; train surgical teams to wait for them to evaporate and to avoid spills (for safety).Disposable applicators could be safer, but these increase costs. | Alcohol-based antiseptic to prepare the field:StrongPreference of alcoholic solution with 2% chlorhexidineModerate |

| Sterile surgical drapes and gowns | Reusable vs disposable material | Moderate to very low | From the standpoint of viability, it is very difficult to prove the impact of these practices on SSI | The availability of disposable surgical drapes and gowns may be low and the cost may be a large financial burden. The economic effect of additional clinical residues generated by these single-use materials should also be considered. | Define the influence of these measures on SSI and their repercussion in different types of surgery. | Sterile surgical drapes and gowns should be used during surgical procedures.They can be used once or more.Conditional(Strong with regards to sterility) |

| Adhesive transparent plastics in the surgical field | Adhesive plastic protectors | Very low | Imprecise and inconsistent | Increased costs; limited availability | Observation bias; need for double-blind studies | The use of transparent adhesive plastics is not recommended.Strong |

| Use of sealants | Application of sealing substances (cyanoacrylate-type) prior to incision | Low quality, few studies | Increased price, with no benefit over adequate skin preparation | Increased cost; availability of application at each hospital | More prospective randomized studies are needed comparing costs/benefits | The use of sealants is not recommended.Strong |

| Surgical retractors during the procedure | Placement of impermeable retractor devices/protectors for laparotomy | High | A substantial part of studies include different impermeable devices, although the most frequent are those using fixation rings. | More evidence is required in dirty surgery, although their use is recommended in any type of laparotomy. | Classification of the benefit of the use of the device according to surgery type | Impermeable retractor, preferably double-ring, in any laparotomy.Strong |

| Optimization of patient homeostasis I | Normoglycemia | Low | Lack of solid evidence outside of cardiovascular surgery; not specified at what time it is most important; possible side effects of strict control | Difficult to establish a precise range for the glycemia desired; need for monitoring | Real benefits and risks in general and gastrointestinal surgery | Non-strict perioperative control of glycemia is recommended in diabetic and non-diabetic patients.Objective: levels <150–200 mg/dLStrong |

| Optimization of patient homeostasis II | Normovolemia | Low | Lack of evidence on the specific measures and objectives of perioperative management | Lack of evidence on specific measures of the management by objectives protocol; specific determinations are required | Determine whether the benefit is more global for the patient and not only for the prevention of SSI | A control by objectives of volemia is recommended to avoid the deficit as well as the of extracellular volume, and appropriate cardiovascular activity.Optimization of patient homeostasisConditional |

| Optimization of patient homeostasis III | Normothermia | Moderate | Lack of consensus in anesthesia protocolsDifficult application in patients with complex surgical fields | Difficult reliable measurement of perioperative core temperature | Specific time and place | The application of perioperative measures are recommended to maintain core temperature ≥36°C in all major surgery procedures >30 minutes.Strong |

| Optimization of patient homeostasis IV | Hyperoxygenation | Moderate-Low | Lack of consensus in the real world of anesthesiology | The adverse effects have not been evaluated as main outcomes. | Actual value of the benefit obtained with hyperoxygenation and possible side effects | Perioperative hyperoxygenation is not recommended with an FiO2 of 80%. |

| Operating room ventilation systems | Ventilation with laminar flow | Low | Most studies focus on orthopedic prosthetic surgery. There are very few studies in abdominal or soft-tissue surgery. | Studies are needed with a representative number of patients in the field of general surgery. There are not several clinical studies of quality to generate evidence. | Studies are needed in the field of abdominal surgery. | The use of ventilation systems with laminar flow is not recommended.Weak |

| Use of double gloves | Double gloves | Insufficient | No relationship between double glove and SSI | Recommended by medical societies and in hospital protocols, in many cases more as a systemic measurement of universal protection. | Double gloves reduce the perforation of the internal glove. | Double gloves are suggested for protection of the surgical team (as a measure of universal protection)Conditional |

| Suture material coated with antiseptic | Sutures coated with triclosan | Moderate | Studies done mainly in colorectal surgery | Major cost; not available in all hospitals | Greater availability and cost reduction; evidence in contaminated and dirty surgery | Their use is suggested, if available, especially in clean and clean-contaminated surgery, as an additional measure for prevention of SSIConditional |

| Irrigation of the abdominal surgical wound prior to closure | Irrigation of surgical wound with topical antibiotic solutions, antiseptic solutions or saline solutions, versus no irrigation | Low | Heterogeneous clinical trials with an elevated risk of bias, mainly due to insufficient data reporting and methodological defects | There are no clear guidelines about the quantity of saline to use (in mL) or optimal concentrations of antiseptic. | High-quality evidence is anxiously being awaited from future clinical trials. The clinical relevance needs to be balanced against the risk of altered wound healing and the potential increase in antimicrobial resistance. | Lavage is suggested with saline as a ‘dragging’ measure and to eliminate detritus.Aqueous povidone-iodine solution could be beneficial, particularly in clean and clean-contaminated wounds.Irrigation with antibiotic solutions is not recommended.Conditional |

| Change of material for wall closure | New sterile instruments for closure | Low | No controlled study in dirty surgery | Increased costs and time | It is assumed that any grossly contaminated materials should be changed. Ethically, no controlled studies will be done.Bundles that include this measure reduce SSI. | A change of surgical instruments and auxiliary material is suggested (suction tips, electric scalpel, lamp sleeves) before closing wounds in clean-contaminated, contaminated and dirty surgery.Conditional |

| Glove change | Glove change every 2 hours or when changing from contaminated to clean fields | Low | There is little evidence on its real impact. Sufficient evidence is assumed if there is visible contamination or breakage of the glove. | Current evidence comes from bundles that include this measure. | Establish real utility and optimal times for the change. | Glove changes are suggested when perforation or contamination is suspected, after gastrointestinal anastomosis, routinely in operations of more than 2h, before inserting a prosthesis and before closing the incision.Conditional |

| Postoperative protection of the surgical wound | Impermeable plastic dressings versus conventional dressings | Low | Imprecise; few studies | Correct maintenance of surgical wound protection with the dressing; training of health staff and patient | Staff should be trained not to lift the dressing if not necessary and avoid unnecessary manipulation of the wound at all times. | Sterile conventional dressing is recommended to cover the wound 48 h.Conditional |

| Negative pressure therapy on wounds with primary closure | Negative pressure therapy system on closed wound | Low | Studies in open colorectal, gynecological and vascular (groin) surgery | High cost, low availability; need for low-cost portable devices | Establish which wounds are high-risk; availability and costs | The use of negative pressure therapy over closed wounds is suggested in patients with high risk of infection.Conditional |

Various measures have been proposed to reduce the incidence of SSI. Many have been evaluated in controlled studies, in some cases with opposing results, while others are the result of clinical observation or routine surgical practice and it would be difficult to subject them to structured scientific analysis. Periodically, scientific societies and national or international entities issue clinical practice guidelines based on the analysis of available scientific evidence. Although all are based on the same original evidence, they often fail to reach similar conclusions, probably due to a combination of reasons: not all prophylactic measures have been sufficiently evaluated; there is variability in the inclusion and exclusion of clinical studies in systematic reviews; and, finally, different evaluation systems and quality-of-evidence grades are used. Furthermore, expert groups introduce their own bias into the final evaluation. The result is a disparate follow-up of prophylactic measures and guideline recommendations.4

A group of core measures with a high level of evidence was identified; these are recommended by most guidelines and should be applied in all surgical procedures. These include preoperative patient showering, washing of hands by the surgical team, antibiotic prophylaxis, no body hair removal (or doing it with an electric razor), antisepsis of the patient's skin with alcohol solutions and maintenance of normothermia, normovolemia and normoglycemia. Furthermore, there is another group of auxiliary measures with a lower level of evidence that can be suggested according to the type of surgery, the local incidence of SSI and the available resources. These include protecting the margins of the laparotomy with a plastic double-ring device, sutures impregnated with antiseptic, changing gloves and surgical material before concluding a contaminated procedure, or negative pressure therapy on the closed wound in higher-risk surgery.

The selection and grouping of these measures into systematized packages or bundles has demonstrated their efficacy in various types of surgery.113,114 Protocolization and control of the follow-up with checklists have led to improvements in the surgical process and a decrease in the SSI rates.115

The reduction of postoperative infection is the paradigm of teamwork. The surgical team, made up of surgical nurses, anesthetists and surgeons, must work in coordination with the ultimate objective of improving patient care by following the best scientific evidence available and forgetting actions that do not add value or are supported by doubtful evidence. However, in the fight to reduce surgical infection, there are still factors for which we have few data that can be systematized, so a meticulous surgical technique and adequate criteria for selecting the most appropriate prophylactic measures continue to be essential.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Badia JM, Rubio Pérez I, Manuel A, Membrilla E, Ruiz-Tovar J, Muñoz-Casares C, et al. Medidas de prevención de la infección de localización quirúrgica en cirugía general. Documento de posicionamiento de la Sección de Infección Quirúrgica de la Asociación Española de Cirujanos. Cir Esp. 2020;98:187–203.