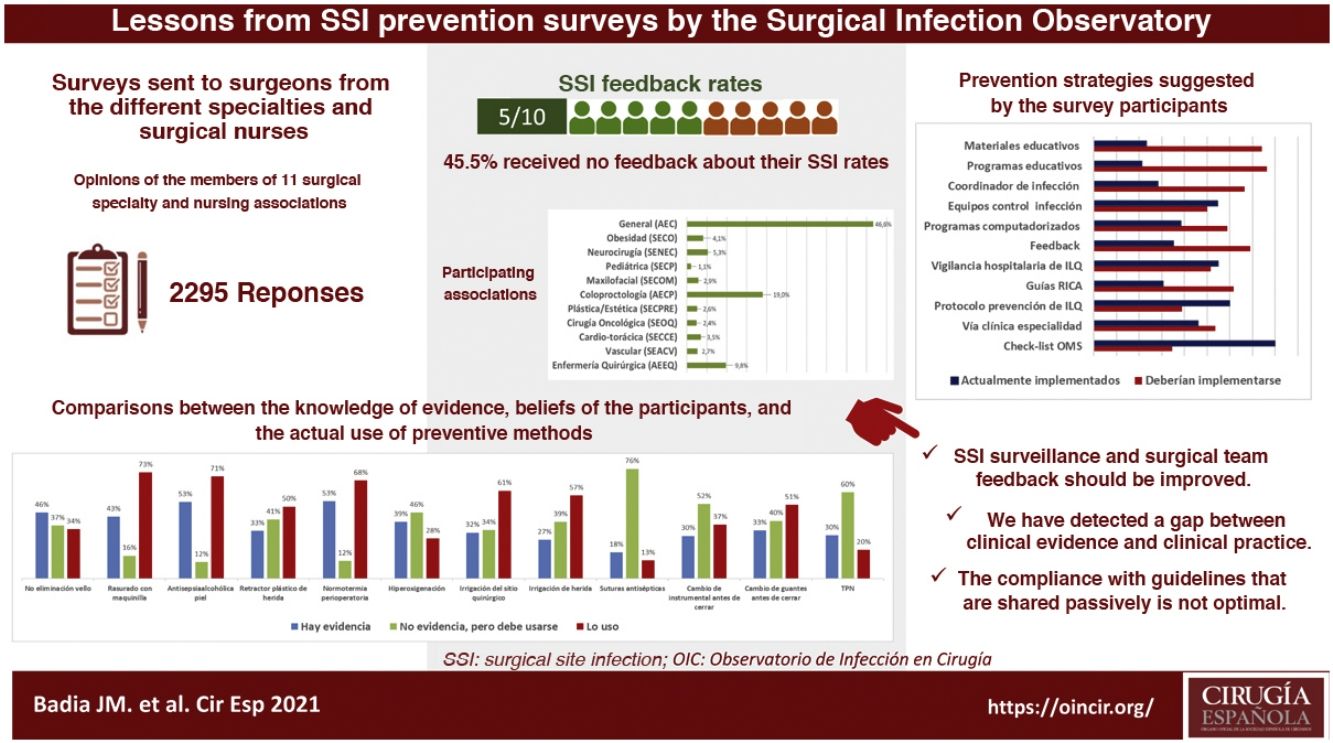

Before planning improvement strategies, it is crucial to know the degree of implementation of preventative measures for postoperative infection. The aggregated results of 3 surveys carried out by the Observatory of Infection in Surgery to members of 11 associations of surgeons and perioperative nurses are presented. The questions were aimed to determine the knowledge of the scientific evidence, personal beliefs and the actual use of the main measures. Of 2295 respondents, 45.1% did not receive feedback on the infection rate of their unit. Insufficient knowledge of some of the main prevention recommendations and some disturbing rates of use were observed. The preferred strategies to improve compliance with preventive guidelines and their degree of implementation were investigated. A gap between scientific evidence and clinical practice in the prevention of infection in different surgical specialties was confirmed.

Antes de planificar estrategias de mejora, es crucial conocer el grado de implementación de las medidas preventivas de infección postoperatoria. Se presentan los resultados agregados de 3 encuestas realizadas por el Observatorio de Infección en Cirugía a miembros de 11 asociaciones de cirujanos y enfermería quirúrgica. Las preguntas fueron dirigidas a determinar el conocimiento de la evidencia científica, las creencias personales y el uso real de las principales medidas. De 2.295 encuestados, el 45,1% no recibe feedback de la tasa de infección de su unidad. Se observó un conocimiento insuficiente de algunas de las principales recomendaciones de prevención y unas tasas de utilización, en ocasiones inquietante. Se indagó sobre las estrategias preferidas para mejorar el cumplimiento de las pautas preventivas y su grado de implementación. Se confirmó la brecha existente entre la evidencia científica y la práctica clínica en la prevención de infección en diferentes especialidades quirúrgicas.

Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most common postoperative complication and has become the most common healthcare-related infection in Spain (27.2%)1 and Europe (19.6%)2. It reaches rates of up to 20% in colorectal surgery3 or 45% after surgery for head and neck cancer4, representing a substantial burden for patients as well as healthcare systems5–7.

The more than 50 perioperative measures proposed to reduce SSI rates are periodically analyzed by national and international health organizations, which prepare clinical practice guidelines based on the level of scientific evidence detected. These guidelines should translate all the scientific knowledge into solid recommendations based on systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and their diffusion among hospitals and surgeons should improve infection rates. Nonetheless, high rates of infection persist, distributed heterogeneously between specialties and hospitals. In addition, the level of knowledge and compliance with SSI prevention protocols seem to vary greatly8, and low compliance with clinical guidelines, bundles of prevention measures and checklists has been reported. Acceptance of and compliance with these guidelines often require substantial cultural and organizational changes, and surgeons have been identified as key factors in noncompliance9.

This project was designed by the Surgical Infection Observatory and consists of 3 surveys aimed at surgeons and surgical nurses from different specialties in order to determine the current level of knowledge and compliance with these recommendations in the surgical services of Spanish hospitals. Although the survey results have been published separately, we have aggregated the data and made comparisons with the recent SSI prevention recommendations of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC) to make general surgeons aware of the main problems detected.

MethodsWe present aggregated data from 3 surveys that had been designed to determine the degree of application of the main prevention measures for postoperative infection proposed by international scientific entities. In total, members from 11 Spanish surgical associations were invited to participate, including the surgical nursing association and surgeons from different specialties. The questions were aimed not only at knowing the real rate of use of these measures, but also at identifying the degree of knowledge of the scientific evidence that supported them and the personal beliefs of the survey participants.

The surveys were created through a web platform (SurveyMonkey), conducted between 2016 and 2019, and distributed via email, society newsletters, and Twitter to members of each of the participating societies. Recipients were instructed not to complete the survey 2 times if they were members of multiple societies. The questionnaire included questions about personal demographics (position, years of experience) and the workplace (type, size, location of hospital). There were 2 main types of questions: some aimed at determining the actual use of the measures in their hospital, and others inquiring about the participant’s personal preferences and level of knowledge about the existing evidence for the different measures.

The questionnaires were designed by a central team with previous experience in preparing surveys and were submitted for evaluation to a panel of experts from the medical societies involved. Direct, unambiguous, simple and impartial questions were developed in an attempt to avoid directed questions. For the most part, these were structured questions that covered all possible alternatives to ensure that each answer was unique. For several questions, general response options (such as ‘other’ or ‘do not know’) were included at the end to ensure effective collection of the potential diversity of responses.

The questions addressed the level of agreement between the survey participants’ beliefs versus the protocols or usual practice of their surgical units. The rate of agreement between the beliefs and the habitual practice of all the respondents was calculated on a scale from 0 to 100. Once the questionnaires were defined, small tests were carried out (10 people, with at least one member of each association) to make sure that the respondents had understood the questions and that the information necessary for the study was being captured. Several internal control questions were included, and the consistency of the answers was checked. Each survey remained open for 3 months, and those invited to participate received several reminder emails or Twitter messages.

The answers have been compared with the recommendations of the most recent clinical practice guidelines: the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO)10 and the Center for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC)11, in addition to those of the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in its 200812 and 201913 updates; the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Surgical Patient Safety of the Spanish National Healthcare System (2010)14; the Canadian Patient Safety Institute Guideline (2014)15; the 2014 update of the SHEA/IDSA Recommendation16, the National Health Service Scotland Guideline (2015)17; the Surgical Site Infection Guidelines of the American College of Surgeons; and the Surgical Infection Society, update from 201618; the recommendations of the Spanish Association of Surgeons from 202019; and the Zero Surgical Infection Project recommendation20. A comparative summary of some of these recommendations is shown in Table 1. The results highlight the most relevant or those that the working group considered important deviations from the clinical guidelines.

Summary of the main presentation measures for postoperative infection according to the most recent national and international clinical practice guidelines.

| Preventive measure | MSPSI, 2010 | CPSI, 2014 | SHEA/IDSA, 2014 | HPS, 2015 | ACS/SSI, 2016 | OMS, 2016 | CDC, 2017 | NICE, 2008, 2019 | AEC, 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vigilance of SSI rates and WHO feedback | Yes (moderate) | ||||||||

| Checklist | Yes (high) | ||||||||

| Adequate intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis | Yes (strong) | Yes (strong) | Yes (high) | Yes (strong) | Yes | Yes (strong) | Yes (strong) | Yes (strong) | Yes (strong) |

| Preoperative bath or shower | YES (strong) | Yes (strong) | Yes (strong) | Yes | Yes (moderate) | Yes (strong) | YES (strong) | YES (strong) | |

| Decolonization S. aureus with mupirocin | In carriers and high-risk surgery (weak) | Yes | In high-risk cardiac surgery (cardiac, OTS) (moderate) | Screening according to risk | Screening according to risk | In carriers and high-risk surgery (cardiac, OTS) (moderate) | Screening according to risk | Conditional in general surgery with stent placement | |

| Decolonization in carriers (strong) | Decolonization in carriers | Decolonization in carrier (strong) | |||||||

| Interruption of immunosuppressant treatment | Do not interrupt (conditional) | Unresolved | Do not interrupt (conditional/weak) | ||||||

| Management of body hair | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) (strong) | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) (moderate) | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) (moderate) | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) (strong) | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) (strong) | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) (strong) | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) (strong) | Do not remove (if necessary: electric razor) (strong) |

| Mechanical colon preparation (MBP) | No (strong) | No (high) | No (moderate) | No (strong) | No (high) | No (strong) | |||

| Oral antibiotic prophylaxis + MBP | Yes (high) | Yes (moderate) | Yes | Yes (conditional) | YES (strong) | ||||

| Product for surgical hand hygiene | First: antiseptic soap + water | Water + antiseptic soap (strong) | Antiseptic soap + water or alcohol gel | Antiseptic soap + water or alcohol gel (strong) | First: antiseptic soap + water | First: antiseptic soap + water | |||

| Then: alcohol gel (strong) | Then: antiseptic soap + water or alcohol gel (strong) | Then: antiseptic soap + water or alcohol gel (strong) | |||||||

| Sterile surgical fields and gowns | Yes (strong) | Yes | Reusable or disposable (conditional) | Reusable or disposable (strong) | Reusable or disposable (conditional) | ||||

| Gloves | Double gloves | Double gloves | Double gloves | Unresolved | Double gloves | Double gloves (conditional)+ | |||

| Preoperative patient skin antisepsis | Chlorhexidine (alternative: povidone) (weak) | Alcohol solution with CH or PI | Alcohol solution with CH or PI (high) | Alcohol solution with CH (strong) | Alcohol solution with CH or PI | Alcohol solution with CH (strong) | Alcohol solution (strong) | Alcohol solution with CH (high) | Alcohol solution (high) with CH (moderate) |

| Antimicrobial sealant after skin antisepsis | No (conditional) | No (weak) | No (strong) | ||||||

| Transparent adhesive plastics in the surgical field | No (strong) | No (high) | Unresolved | No (conditional) | No (weak) | No (strong) | No (strong) | ||

| If required, iodophor-impregnated | |||||||||

| Plastic surgical wound retractors | Yes, plastic 2 rings > 1 (high) | Yes | Yes 1−2 rings (conditional) | Impermeable retractor, preferable double ring (strong) | |||||

| Normothermia | Yes (weak) | Yes | Yes (high) | Yes (strong) | Yes | Yes (conditional) | Yes (strong) | Yes (strong) | Yes (strong) |

| Glycemia control | No (high) | Yes, diabetics (<180 mg/dL) | Yes, cardiac/non-cardiac (<180 mg/dL) (high/mod) | Yes, diabetics (<200 mg/dL) (strong) | Yes, diabetics and non-diabetics (<150 mg/dL) | Yes, diabetics and non-diabetics (<150 mg/dL) (conditional) | Yes, diabetics and non-diabetics (<200 mg/dL) (strong) | Yes, diabetics | Yes, diabetics and non-diabetics (non-strict control, <150−200 mg/dl) (strong) |

| Normovolemia | Adequate perfusion (low) | Goal-directed fluid therapy (conditional) | Goal-directed | ||||||

| Optimization of patient homeostasis (conditional) | |||||||||

| Hyperoxygenation (FIO2 0,8) | No (high) | Yes (high) | No (strong) | Yes | Yes (conditional) | Unresolved | No (high) | No | |

| Peritoneal irrigation with antiseptics/ antibiotics | No (weak) | Yes, povidone (moderate) | Antibiotic: Unresolved | No | |||||

| Antiseptics: no (weak) | |||||||||

| Surgical wound irrigation with antiseptics | Yes (pressurized saline or povidone) (high) | Yes, povidone (conditional) | Yes (povidone) (weak) | No | Yes, saline solution or povidone (conditional) | ||||

| Surgical wound irrigation with antibiotics | No (high) | Unresolved | No (conditional) | Unresolved | No | No (conditional) | |||

| Suture material coated in antiseptic | No (moderate) | No | No (moderate) | Yes, clean and clean-contaminated surgery (if available) | Yes (conditional) | Consider its use (weak) | Consider its use | Consider its use in clean and clean-contaminated surgery (conditional) | |

| Change of material for wall closure | Yes | Unresolved | Yes, surgical instruments and auxiliary material in non-clean surgery (conditional) | ||||||

| Glove changes | Yes | Unresolved | Yes, when contamination or perforation is suspected, at the end of a digestive anastomosis and, routinely, in operations lasting more than 2 h, before placing a stent and before closing the incision (conditional) | ||||||

| Postoperative antiseptic dressings on surgical wounds | Unresolved | No (conditional) | Unresolved | Yes, conventional sterile dressing 48 h (conditional) | |||||

| Negative pressure therapy on primary wound closures | Yes, in high risk | Yes, in high risk (conditional) | Yes, in high risk (conditional) |

When available, the degree of recommendation (strong, moderate, weak) or level of evidence (high, moderate, low) is shown.

Blank: measure not included in the guideline.

Unresolved: no recommendation given due to lack of sufficient evidence either for or against.

Modified from Badia JM et al.19. ACS/SIS: American College of Surgeons/Surgical Infection Society (USA); AEC: Asociación Española de Cirujanos; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA); CH: chlorhexidine; OTS: orthopedic and trauma surgery; CPSI: Canadian Patient Safety Institute (Canada); HPS: Health Protection Scotland, National Health Services Scotland (United Kingdom); MSPI: Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad (Spain); NIHCE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK); WHO: World Health Organization; PI: povidone-iodine; SHEA/IDS Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Infectious Diseases Society of America (USA).

The projects were registered under ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT03883399 and NCT04310878. Results have been written in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) and are expressed as percentages of total responses. Data were analyzed using the SPSS program (v.10.0, Chicago, IL, USA). To analyze the relationship between 2 categorical variables, the chi-squared test was used. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

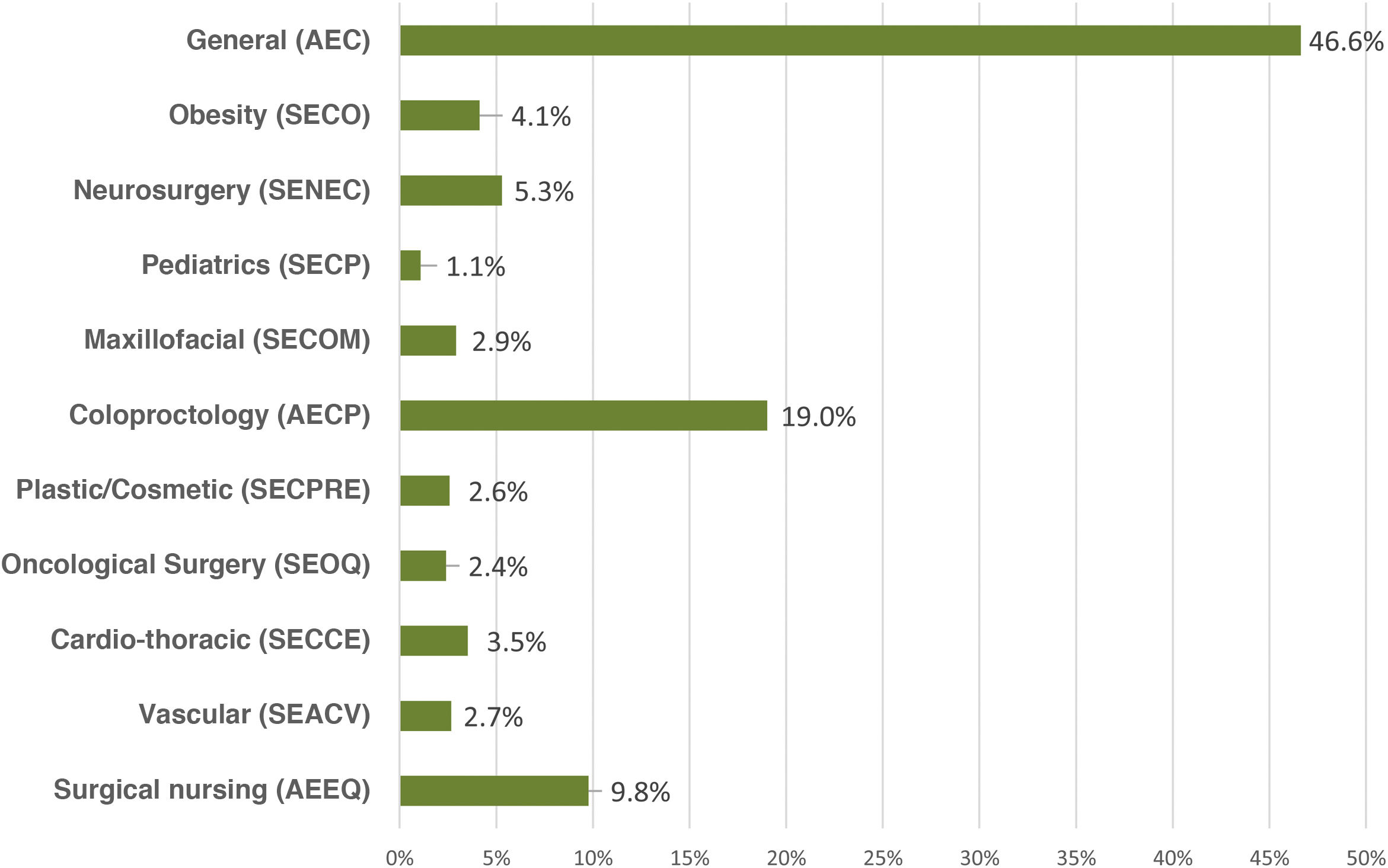

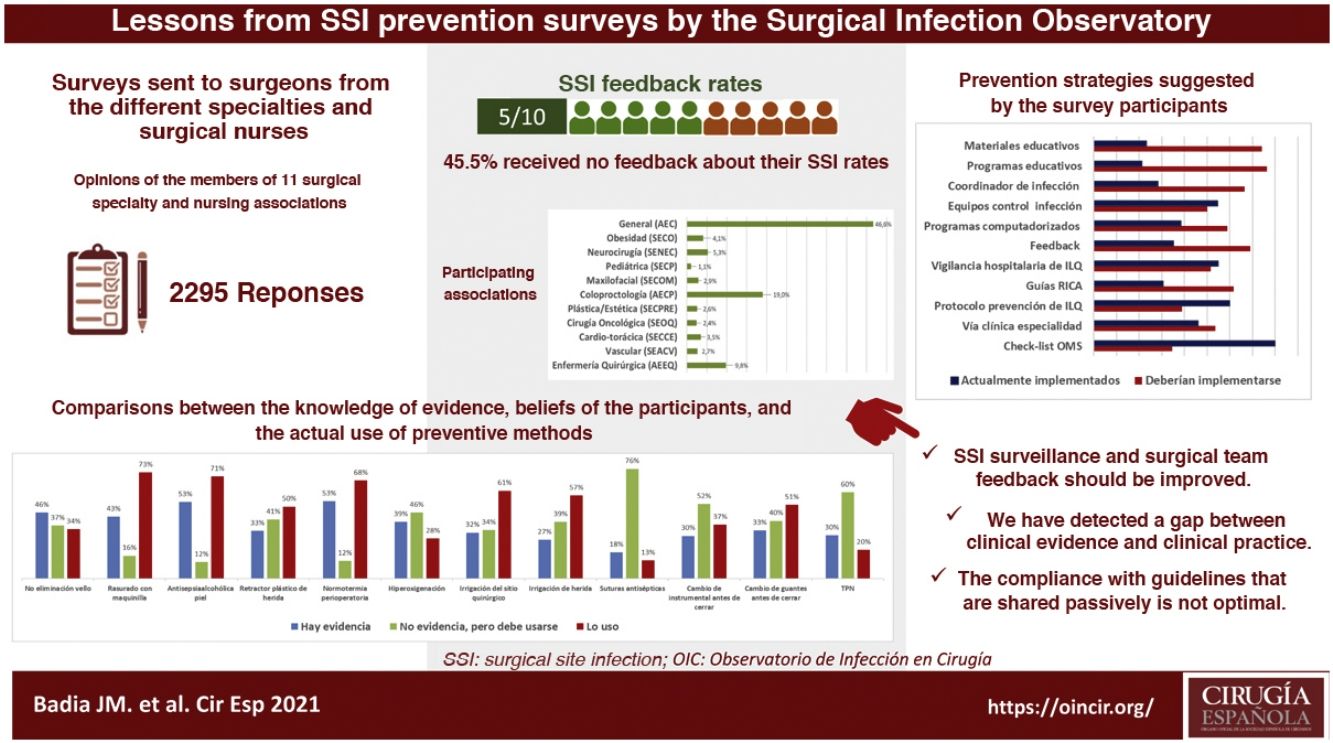

ResultsA total of 2295 nursing and surgical professionals answered the 3 surveys.21–23 Their distribution by scientific society is shown in Fig. 1. Most work in public hospitals (87.6%), half of which are high-volume university hospitals; 61.3% are professionals with more than 10 years of experience.

With variations depending on their specialty, between 25% and 50% of those surveyed do not receive institutional information on their postoperative infection rates, not even in high-volume units and tertiary care hospitals. Significant differences were detected: cardiac surgery (77.5%; chi-squared 18.86; P < .001) and colorectal surgery (68.4%; chi-squared 8.85; P < .001) receive the most information, while ENT surgery receives the least (29.8%; chi-squared 8.78; P < .05).

Most hospitals have operating room safety protocols and surgical patient preparation protocols, although around 15% of those who answered did not know their content.

Survey respondents give little importance to the measures used in their surgery units to avoid SSI (only 46.8% consider them important or very important). In their opinion, national guidelines (90%), international guidelines (87.0%) and hospital protocols (87.5%) are more valuable for the design of prevention measures.

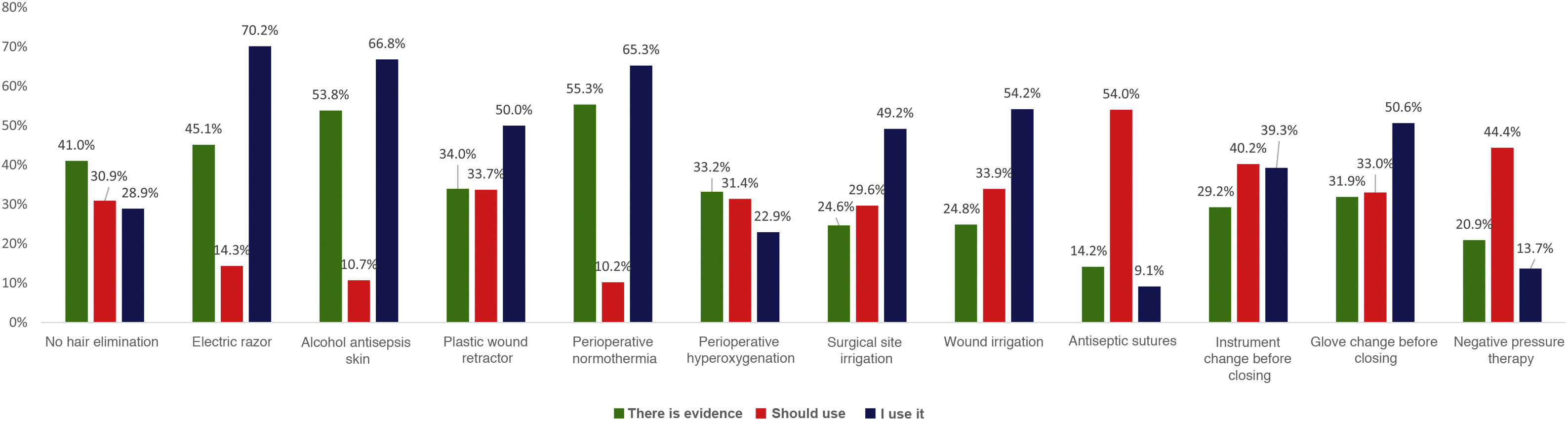

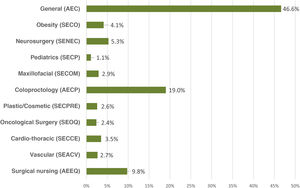

When asked about various recommendations classified as strong in the clinical guidelines, a generally high level of discrepancy was detected between the respondents’ perception of the evidence and the assessment made by the most recent clinical guidelines. For example, the rate of evidence was considered to be only 33% for the use of plastic wound retractors-protectors, 43% for shaving with an electric razor, 46% for not removing skin hair and 53% for antisepsis with alcoholic solutions and maintaining perioperative normothermia. When the levels of application of these recommendations in daily practice are compared with the personal beliefs of the respondents, the results are variable, as shown in Fig. 2. There is a high discrepancy between the value that the respondents give to certain measures (adding the degree of evidence to personal belief) and its clinical use.

The actual level of use of SSI preventive measures is summarized in Table 2. When we compared these rates with the recommendations of the most recent clinical guidelines, potential dysfunctions were detected. It is notable that the overall rate of preoperative nutritional assessment before major surgery is 37% and that 15% of those surveyed indicate preoperative nutritional supplements in previously well-nourished patients. In contrast, 24% state that they do not conduct artificial nutritional interventions in patients with preoperative malnutrition. There were significant differences in the use of preoperative nutritional supplements for well-nourished patients, which were used more by respondents from colorectal surgery societies (44.7%; chi-squared 52.85; P < .001), general surgery (32.4%; chi-squared 62.64; P < .001), surgical oncology (33.3%; chi-squared 10.11; P < .05) and bariatric surgery (29.2%; chi-squared 13.28, P < .001).

Comparison of AEC recommendations to prevent postoperative infection with the results of the utilization of measures by all societies.

| Generic measure | AEC recommendation | Use of the measure (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative nutritional state | Nutritional optimization is recommended according to assessment of the preoperative nutritional state before the procedure | 37 |

| Decolonization of S. aureus with mupirocin | Not recommended in general surgery | 30.3 |

| Conditional in general surgery with stent placement | ||

| Antibiotic prophylaxis and its time of administration | No antibiotic prophylaxis >24 h | 81.2 |

| MBP in elective colorectal surgery | Do not use mechanical colon preparation alone (without oral antibiotic) with the aim to prevent SSI | 96.2 |

| Oral antibiotic prophylaxis in elective colorectal surgery | Oral antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended in association with MBP in elective colorectal surgery. | 32.6 |

| Preoperative shower | It is recommended that the patient take a shower the same day of surgery with chlorhexidine soap or non-pharmacological soap | 94.5 |

| 55.9 | ||

| 37.8 | ||

| Management of body hair | It is recommended not to routinely remove body hair from the surgical field. | 10.2 |

| When necessary, it should be removed outside the surgical unit, never with a blade but instead with an electric razor | 29.9 | |

| 15.8 | ||

| 79.2 | ||

| Surgical hand hygiene | First hygiene of the day with soapy solution | 88.4 |

| Later with antiseptic soap or alcohol solution (allowing it to evaporate) | 36.3 | |

| Antiseptics for the preparation of the surgical field | Alcohol-based antiseptic | 65.4 |

| Preferably chlorhexidine 2% alcohol solution | 57.5 | |

| Adhesive transparent plastics int he surgical field | The use of transparent adhesive plastics is recommended. | 35.7 |

| Impermeable retractors/protectors of the surgical wound in laparotomy | Impermeable retractor, preferably double ring in any laparotomy | 32.2 |

| Normoglycemia | Non-strict perioperative glycemia control is recommended in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. | 59.0 |

| Objective: levels <150−200 mg/dL | ||

| Normothermia | Perioperative measures are recommended to maintain core temperature ≥36 °C in all surgical procedures >30 min. | 88. 4 |

| Hyperoxygenation | Perioperative hyperoxygenation is not recommended with FiO2 80%. | 25.7 |

| Use of double gloves | Double gloves are recommended to protect the surgical team. | 18.9 |

| Suture material coated with antiseptic | Its use is recommended if available, especially in clean and clean-contaminated surgery. | 17.1 |

| Irrigation of the abdominal surgical wound prior to closure | Lavage is recommended with saline solution as a means of «arrastre» and elimination of detritus. | 89.0 |

| Irrigation of the surgical wound with topical antibiotics, antiseptic solutions or saline solutions, versus no irrigation | Povidone iodine aqueous solution could be beneficial, particularly in clean and clean-contaminated wound. | 3.8 |

| Irrigation with antibiotic solutions is not recommended. | 1.5 | |

| Change of sterile instruments for wall closure | Change of surgical instruments and auxiliary material is recommended (suction tips, electric scalpel, sleeves of surgical lamps) before wound closure in clean-contaminated, contaminated and dirty surgery. | 41.3 |

| Glove change every 2 h or when changing from contaminated to clean fields | Glove changes is recommended when contamination or perforation is suspected, after a digestive anastomosis, and routinely in surgeries > 2 h, before stent placement, and before closure of the incision. | 91.4 |

| Negative pressure therapy over wounds with primary closure | Negative pressure therapy is recommended over closed wounds in patients at high risk for infection. | 37.8 |

SSI: surgical site infection; MBP: mechanical bowel preparation.

Systematic screening and decolonization of S. aureus is not recommended prior to general surgery, but it is recommended in other specialties like cardiac or orthopedic surgery. The surveys detected a rate of treatment for eradication in 30.3% of the patients in whom this bacterium is detected during screening.

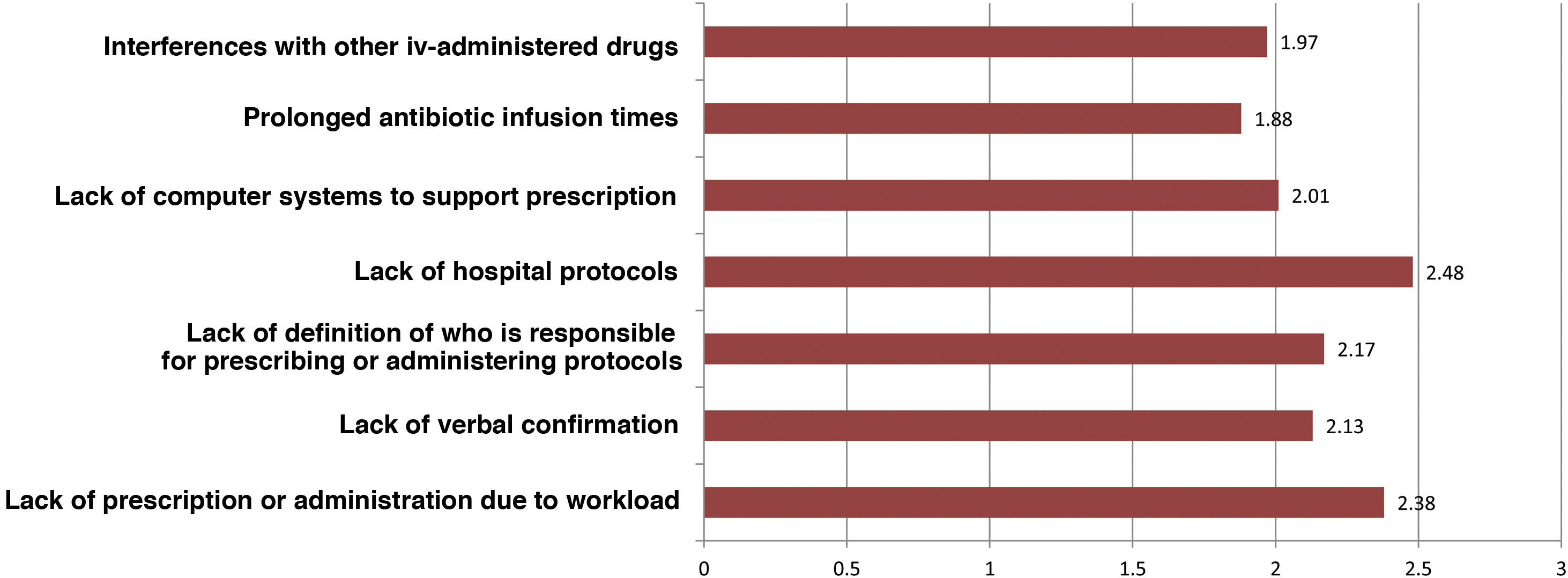

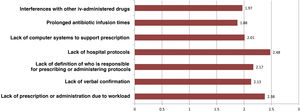

Regarding intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis, 11% of participants affirm that it is always carried out in the hospitalization ward, especially in maxillofacial surgery. Fig. 3 shows the main causes of incorrect adherence to the prophylaxis protocol, which also presents significant differences between specialties. Almost 19% of those surveyed extend the use of prophylaxis for more than 24 h, but this is focused almost exclusively on ENT (42.5%), cardiac (41.2%) or pediatric (11.8%) surgery. The highest rate of preoperative single-dose use for prophylaxis is observed in general surgery (76.4%) and is similar to oncologic (75.6%), bariatric (73%) and colorectal surgery (69.7%).

Preoperative hair removal is performed at the patient’s home in 5.1% of cases, in the hospital the day before surgery in 19.3%, and in the surgical area in 21.1%.

For the antisepsis of the patient’s skin, a notably high rate (80.4%) of use of multi-use bottles (250–500 mL) was found. The antiseptic is mainly applied with gauze and tweezers (91.2%) and with single-dose sterile applicators in 8.8%. A single application of antiseptic is used in 57.9%, while 42.1% made 2 or more applications. As for drying of the antiseptic, 36.3% do so manually with gauze or paper compresses, only 57.3% let it air dry, and 6.4% apply the surgical cover without waiting for it to dry. 28% of those surveyed have heard of an ignition incident in their hospital related to the use of alcohol-based antiseptics in the operating room.

The laparotomy margins are not protected in 9.9% of cases; they are covered with materials permeable to liquids (and bacteria) in 31.2%, and with impermeable devices in 55.2%. Meanwhile, 52.1% of those surveyed do not know whether hyperoxygenation with FiO2 of 0.8 is used in the perioperative period, and 55.7% systematically place drains in elective surgery.

Before concluding the procedure, the majority of the cavities and surgical wounds (85.9% and 89%, respectively) are irrigated, which is done with saline solution in 90% of cases. When asked about antiseptic sutures, only 17.1% of those surveyed use it always or occasionally, probably because 19% are unaware of its existence, 31% believe that there is not enough evidence, and 46.5% do not have this material.

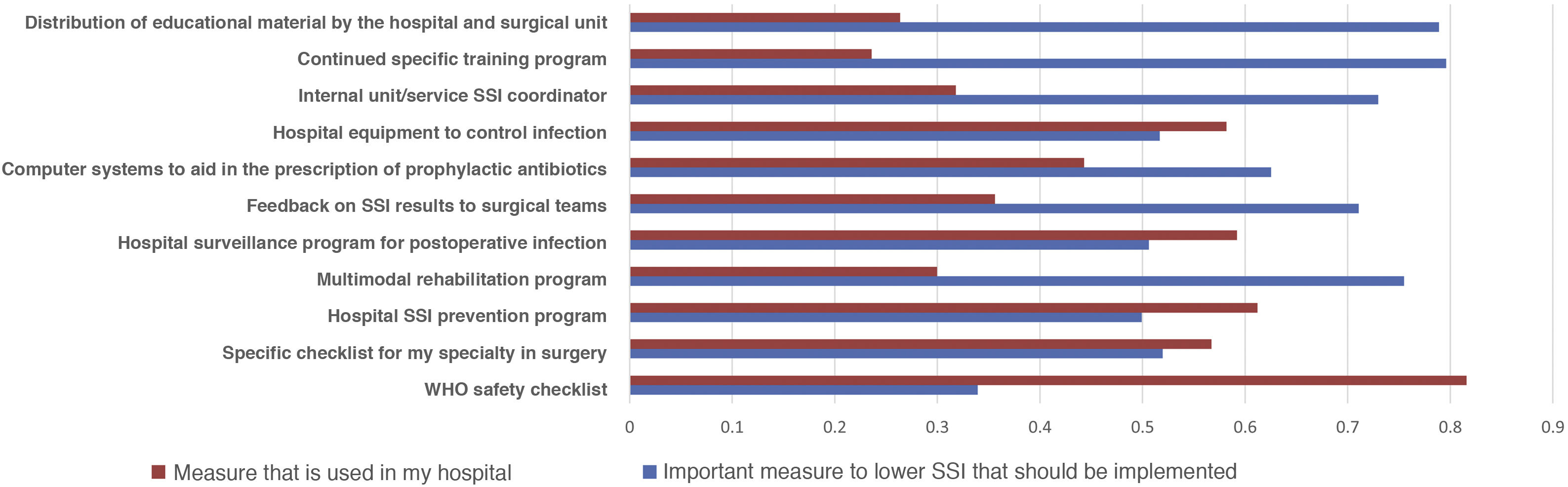

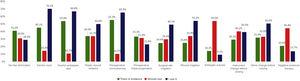

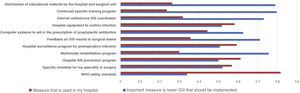

Most of the respondents believe that there is a large discrepancy between the recommendations of the published guidelines and actual clinical practice, which translates into an overall divergence between evidence and practice close to 70%. When asked about potential methods to bring clinical practice closer to the evidence, suggestions included the implementation of educational programs (76.3%), providing information of results to surgical teams (69.1%), naming an SSI coordinator in surgical units (66.5%), encouraging recovery protocols in surgery (RICA or ERAS) (61.7%), computerized prescription aids in hospital digital systems (58.9%), protocols or specialty-specific clinical pathways (53.5%) and centralized infection surveillance and follow-up (51.6%), but they stated that few of these strategies exist in their institutions (Fig. 4).

DiscussionDespite the publication of relevant documents for the prevention of SSI during the last decade, such as the WHO,10 NICE12 or CDC11 guidelines, SSI rates have not decreased substantially or homogeneously among surgical specialties2. It is known that compliance with clinical practice guidelines that are shared passively is not optimal, and it seems that there is a constant discrepancy between the recommendations they contain and daily practice24,25.

The Surgical Infection Observatory (https://oincir.org/) was created in 2018 by the Surgical Infection Division of the AEC with the collaboration of 17 scientific societies, from both medical and surgical fields, that have an interest in postoperative infection. The objective of this present study was to determine the local level of implementation of the measures recommended in the most recent international guidelines and the level of knowledge of surgical professionals about the related scientific evidence. Likewise, we investigated personal beliefs about the use of these recommendations and suggestions for improving infection prevention in hospitals. All this was considered a first step towards the preparation of new bundles of prevention measures, adapted to the reality of Spanish hospitals and actively shared.

The overall level of knowledge of respondents about the scientific evidence related to postoperative infection can be classified as having ‘room for improvement’. Furthermore, when the actual application of the main recommendations is compared with those proposed by current national14,20 and international guidelines or with those published by the AEC in 202019, situations and factors of particular concern have been detected, which should serve as a guideline to address future projects of the Observatory.

For example, there is a high rate of routine hair removal from the surgical field (90%), which is sometimes still done with a blade (16%), at the patient’s home or within the surgical area. The lowest rate of SSI is achieved by not removing the hair26, so it is almost unanimously recommended not to shave it or, if necessary, selectively remove it by shaving with an electric razor with a disposable head as close as possible to the start of surgery and outside the surgical area.

Leaving aside the controversy about the products that should be used for preoperative nutrition and the role of so-called ‘immunonutrition’, it is surprising that only 37% of those surveyed state that nutritional status is evaluated before major surgery. In contrast, in 15% of cases, oral nutritional supplements are provided in patients considered well nourished, surely due to the influence of some prehabilitation programs that include them.

The discrepancy between clinical practice and beliefs about mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) and oral prophylaxis before colorectal surgery is discussed in depth in a previous article. In summary, there is a general feeling among the respondents that oral antibiotic prophylaxis reduces SSI risk, either alone (55.5%) or in combination with MBP (80.4%), but it is only prescribed by 32.6% of surgeons, mostly in combination with MBP (27.6%), with no differences detected between surgeons belonging to high- or low-volume units, or who work in hospitals with or without colorectal units22.

Among other results that draw attention are those related to skin antisepsis. There is a low use of alcoholic gel solutions for the antisepsis of the patient’s healthy skin (65.4%), despite abundant evidence in its favour27,28. Alcohol-based solutions have more immediate activity and, especially when combined with chlorhexidine, more residual activity, which is why they are currently supported by most guidelines. Also, alcoholic solutions cannot be used in certain locations (mucous membranes, ears, eyes, mouth, neural tissue, open wounds, non-intact skin) and their concentration must be limited to avoid burns. It is important to emphasize that the reintroduction of alcohol in operating rooms can represent a safety problem due to the risk of ignition29. More than one-quarter of those surveyed are aware of a safety problem related to alcohol in their operating rooms. Regardless of the antiseptic used, it is imperative to allow antiseptic solutions to air dry in order to maximize their effectiveness and prevent a fire hazard15. In addition, the bad habit of blotting antiseptic with gauze or absorbent paper towels may accidentally violate asepsis if areas not treated with antiseptic are inadvertently touched. Our survey shows an alarming rate of mechanical drying (36.3%) before applying the surgical cover, which limits the time necessary for the antiseptic to act (3 min). Also, 6.4% of surgeons apply surgical drapes without waiting for them to dry, which represents a real risk of ignition when alcoholic solutions are used, especially combined with plastic covers. The present survey shows that the use of alcohol is associated with a significant increase in spontaneous drying. Alcohol, with its accelerated evaporation, probably facilitates compliance with drying time protocols, avoids gauze drying, and allows for the minimum required antimicrobial action time. Single-use applicators could also encourage more standardized practice and the use of less antiseptic for skin preparation.

A high use of adhesive plastic surgical drapes has been found. These devices are designed to reduce contamination of the wound with microorganisms from the patient’s skin, (35.7%), but there is no evidence that they reduce SSI. There is even some evidence that they increase it30, their use is discouraged by most current guidelines. When considered necessary, some authors recommend using iodophor-impregnated plastic adhesive drapes.

The rate of protection of laparotomy margins seems insufficient, as does the use of double-ring plastic retractors (32.2%), which would be recommended according to the results of several meta-analyses31,32. Excessive prolongation of antibiotic prophylaxis has also been detected, as some specialists extend prophylaxis for more than 24 h, especially in cardiac, cosmetic, and head and neck surgery.

We believe that other measures with little or no scientific evidence that are dictated by surgical ‘common sense’ and supported by their inclusion in some successful prevention bundles33 could be more widely used. Examples of these would be the use of double gloves (used by only 19%) and intraoperative changing of gloves, surgical and auxiliary material after a digestive anastomosis or before closing a laparotomy. Irrigation of the surgical wound with pressurized saline is a measure still under evaluation that is not recommended by most clinical guidelines, although new evidence in favour of its use is periodically published34. This would support its efficacy in removing debris, clots and bacteria from the subcutaneous space and its almost universal use in all types of surgery in our setting (89%).

A controversial measure that is under review, perioperative hyperoxia, is rarely used (25.7%), although more than half of the survey respondents state that they do not know whether their anesthesiologists use it. This would indicate a lack of teamwork and internal communication in our operating rooms, which is a factor not analyzed in the surveys.

However, we feel that the most worrying finding of the study is the low level of information on SSI rates in Spanish hospitals, which is more worrying, if possible, in tertiary hospitals and specialized units with high surgery volumes. The first step to improve SSI rates in a country is the establishment of surveillance programs for nosocomial infection, accompanied by information for surgical teams35.

The comparison of the most relevant measures to bridge the gap between the evidence of practice and the reality of its implementation is striking (Fig. 4). It shows that the proposals considered most important by the respondents are precisely the least implemented in their hospitals. Among them, once again, is information on SSI rates for surgical teams.

Some similar surveys have been published, but most have been carried out in specific geographic areas (city hospitals25 or regional hospitals24,36) or in specific surgical procedures (such as arthroplasty37, coronary artery bypass38 or caesarean sections39). Some surveys have been addressed to operating room nurses40 and others to members of specific surgical societies, such as pediatric surgery41. To date, the Surgical Infection Observatory surveys have obtained the greatest number of responses and provide the opinion of surgeons from various specialties and surgical nursing nationwide and go deeper into specialties with a high risk of postoperative infection, such as colorectal surgery.

The project has several limitations. First, it is difficult to accurately calculate the response rate to the surveys, given the uncertain number of members from different medical associations that received the invitation. However, the absolute number of respondents is very high and seems sufficiently representative in each of the surgical specialties. In addition, there seems to be a balanced representation of different types of hospitals (size, teaching, public/private), which indicates that the results can be generalized to the reality of surgical practice in our country. Second, the study may also be limited by a self-assessment bias, as self-assessments have been shown to overestimate one’s own results42.

In short, it seems that the indication of a preoperative shower, staff hand hygiene, use of impermeable surgical drapes and perioperative normothermia are the measures with which Spanish nurses and surgeons are closest to current practice guidelines. Other measures, such as irrigation of surgical cavities and washing of wounds with saline solution, are frequently used, probably due to empirical habits and so-called ‘surgical tradition’. In contrast, some measures that are highly recommended by the main guidelines are not sufficiently implemented. These include: not removing hair routinely in patient preparation protocols, but instead according to the patient’s circumstances and the type of surgical procedure; do not shave the hair with a metal blade; use alcohol-based solutions for skin antisepsis; respect the air-drying time of the antiseptic solution; standardize an intraoperative glove change protocol; and, generalize the use of wound margin protectors that are impermeable to liquids and bacteria.

It is essential to determine the degree of knowledge of professionals about the scientific evidence and the level of implementation of SSI prevention measures. Our results indicate that a gap persists in translating the best evidence into actual surgical practice for SSI prevention, and even in academic settings. The Surgical Infection Observatory has proposed unifying all these findings, analyzing the negative attitudes of professionals and the causes of non-compliance with the measures, and aims to be a forum to share solutions, increase compliance with prevention recommendations and improve education in surgical infection. The design of bundles or packages of preventive measures, which should be shared through active methodologies should reduce SSI rates homogeneously among specialties and hospitals. These implementation policies should receive the support of scientific societies and official healthcare institutions and focus not only on surgical professionals but also on the context in which they work.

FundingThe surveys have received funding from the Surgical Infections Observatory (Observatorio de Infección en Cirugía) from a Technology and Healthcare Foundation (Fundación Tecnología y Salud) grant.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare regarding this publication.

Bader Al-Raies Bolaño, Servicio de Cirugía Vascular, Hospital de Manises (Valencia); Elena Bravo-Brañas, Servicio de Cirugía Plástica, Estética y Reconstructiva, Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid); Ramón Calderón Nájera, Servicio de Cirugía Plástica, Estética y Reconstructiva, Hospital Ruber Internacional (Madrid); Manuel Chamorro Pons, Servicio de Cirugía Oral y Maxilofacial, Hospital Ruber Juan Bravo (Madrid); Cecilia Diez, Àrea Quirúrgica, Hospital Universitari Sant Pau (Barcelona); Xosé M. Meijome, Gerencia de Asistencia Sanitaria del Bierzo (León); José López Menéndez, Servicio de Cirugía Cardíaca, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Madrid); Julia Ocaña Guaita, Servicio de Cirugía Vascular, Hospital Ramón y Cajal (Madrid); Gloria Ortega Pérez, Servicio de Cirugía Oncológica, MD Anderson Cancer Center (Madrid); Rosa Paredes Esteban, Unidad de Cirugía Pediátrica, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía (Córdoba); Antonio L. Picardo, Unidad de Cirugía Endocrina, Metabólica y Bariátrica, HM Montepríncipe (Boadilla del Monte, Madrid); Cristina Sánchez Viguera, Servicio de Neurocirugía, Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga (Málaga); Ramón Vilallonga, Unidad de Cirugía Endocrina, Metabólica y Bariátrica, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebrón (Barcelona).

Members of the del Surgical Infection Observatory workgroup are listed in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Badia JM, Amillo Zaragüeta M, Rubio-Pérez I, Espin-Basany E, González Sánchez C, Balibrea JM, et al. ¿Qué hemos aprendido de las encuestas de la AEC, AECP y del Observatorio de Infección en Cirugía? Cumplimiento de las medidas de prevención de infección postoperatoria y comparación con las recomendaciones de la AEC. Cir Esp. 2022;100:392–403.