Adrenal tumors detected in pregnancy are uncommon but potentially very serious because the pathophysiological impact on the mother and fetus can be severe.1 Ganglioneuromas are uncommon neurogenic tumors that are derived from the neural crest and are located primarily in the posterior mediastinum and/or retroperitoneum. In 20%–25% of cases, they occur in the adrenal gland,2,3 although their diagnosis during pregnancy is exceptional.4 However, these tumors that are diagnosed during gestation require different management, as it is necessary to avoid radiological studies that expose the fetus to important radiation, teratogenic medications and surgery, which should be deferred as long as possible. We present a case of adrenal ganglioneuroma diagnosed during gestation, where surgical treatment was deferred.

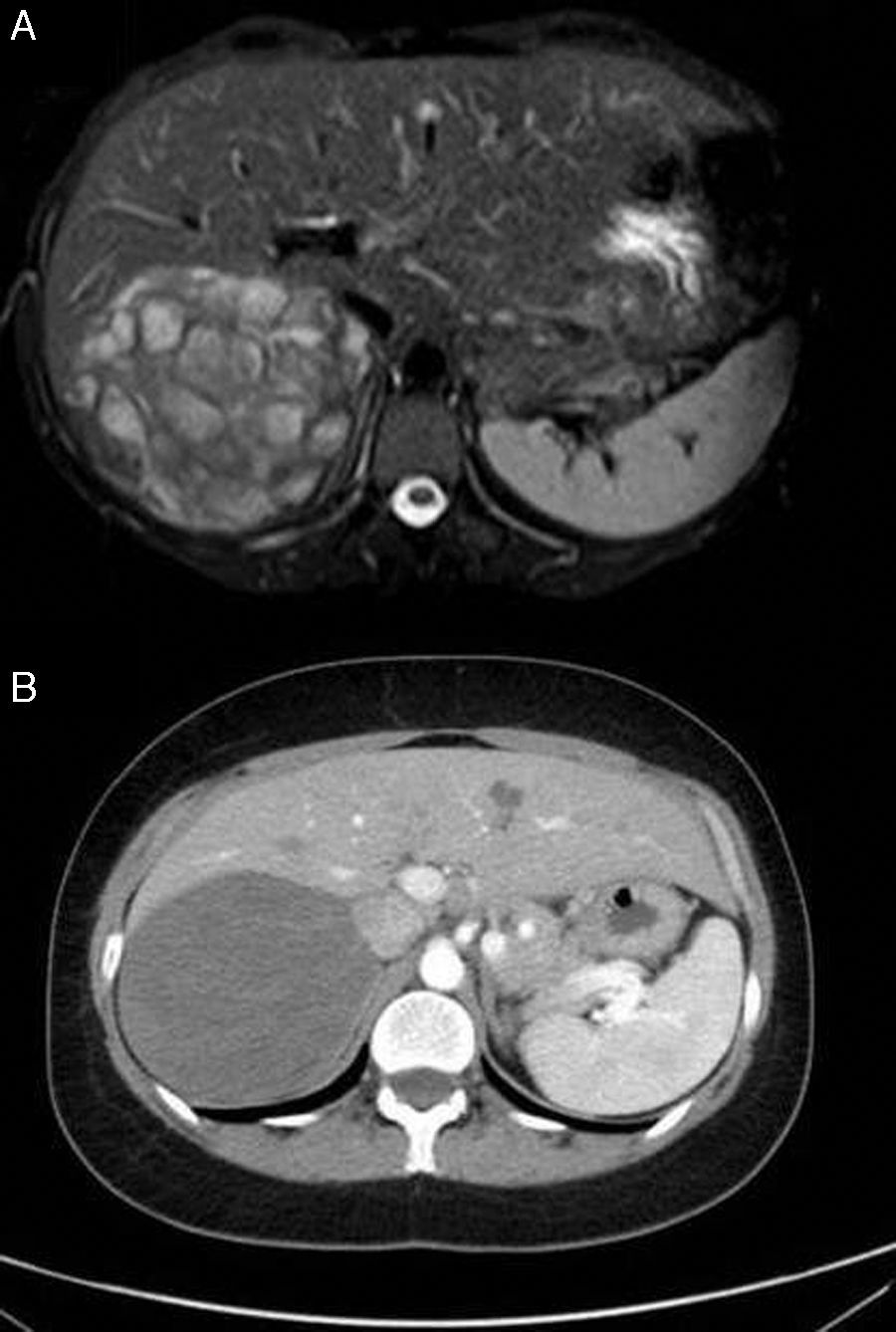

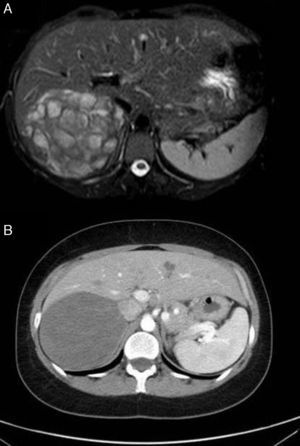

A 38-year-old, 25-week pregnant woman with hepatitis B virus was diagnosed with a right adrenal mass on a prenatal ultrasound. After this finding, a complete adrenal functional study was performed, obtaining an aldosterone level of 466pg/mL (normal: 7–150) and the remaining values were normal (serum cortisol, ACTH, catecholamines and cortisol). Due to the pregnancy, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was not performed to avoid radiation to the fetus. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study revealed a well-defined right adrenal mass measuring 11×7.5cm, and the internal signal was heterogeneous in T2, suggestive of ganglioneuroma (Fig. 1A). As it was non-functioning and MRI showed no signs of malignancy, the patient was periodically monitored. A planned cesarean delivery was indicated, which was conducted without complications for the mother or the child. After delivery, the study was completed with an abdominal CT scan, which confirmed the MRI findings and showed no further growth (Fig. 1B). The repeated hormonal study was normal, with normalized aldosterone levels. With a diagnosis of an undefined adrenal tumor, the mass was removed one month after cesarean section. There were no postoperative complications. The histopathological study defined the tumor as an adrenal ganglioneuroma, and the patient continues to be asymptomatic 7 years after surgery.

Because of their infrequency, there are few published series of adrenal ganglioneuromas.5–9 Patients are usually young (30–50 years of age), with a slight predominance of females and right-side involvement. The diagnosis is usually made incidentally. In these patients, it is important to determine whether the lesion is functioning and/or malignant in order to assess the possibility of delaying definitive treatment until after childbirth. It should be remembered that most are usually non-functioning, so waiting for the fetus to come to term is therefore possible. However, certain ganglioneuromas secrete catecholamines, aldosterone, cortisol and/or testosterone, which can lead to hypertension, Cushing's syndrome or virilization of the patient. This is particularly serious during pregnancy as it increases the risk for eclampsia. In our case, the fact that there was an increase in plasma aldosterone levels did not mean that it was a functioning tumor, since the increase of maternal progesterone during gestation acts as an antagonist of renal mineralocorticoid receptors, thereby increasing urine sodium levels and thus increasing plasma aldosterone levels.1 Their normalization after childbirth confirms this in our case. If elevated aldosterone levels persist, the patient should be tested for hyperaldosteronism. Finally, we should mention that the majority of these lesions are benign, and few patients have presented malignant degeneration.5–9

The diagnosis of adrenal incidentaloma in pregnancy requires an appropriate approach to its diagnosis and treatment according to functionality, size and radiological characteristics, while contemplating the risks/benefits of surgery. Thus, in tumors that are functioning, malignant or possibly malignant, or that cause important symptoms due to their large size, tumor resection should be considered, which as a rule is conducted in the second trimester. If diagnosed in the third trimester, surgery should be delayed until after childbirth, unless the lesion poses a serious threat to the lives of the mother and the fetus.

If there is a high suspicion that the incidentaloma is a ganglioneuroma due to its radiological characteristics and the benign nature of the lesion, it is reasonable to postpone surgery until after childbirth, as in our case. In this situation, MRI is the basic test used to study an adrenal tumor during gestation.4 In our case, although the tumor was very large, we decided not to perform surgery during gestation because it was non-functioning, there were no radiological findings suggestive of malignancy, and given the state of advanced gestation.

Authorship- 1.

Manuscript concept and design: A. Ríos and L.F. Alemón.

- 2.

Data collection: L.F. Alemón and J. Ruiz.

- 3.

Data analysis and interpretation: A. Ríos, L.F. Alemón, J. Ruiz and J.M. Rodríguez.

- 4.

Composition, review and approval of the final manuscript: A. Ríos, L.F. Alemón, J. Ruiz and J.M. Rodríguez.

Please cite this article as: Ríos A, Alemón LF, Ruiz J, Rodríguez JM. Ganglioneuroma suprarrenal en una mujer gestante. Cir Esp. 2017;95:49–51.