Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is an unusual etiology of chronic pancreatitis, involved in approximately 6% of all cases.1 It is a systemic disease that affects the pancreas as well as other organs, such as the bile duct, salivary glands, lymph nodes, kidneys and retroperitoneum.

It was first described in 1961 by Sarles et al.2 Since then, our understanding of this entity has increased immensely, although some controversy still remains regarding the diagnostic and therapeutic criteria, as demonstrated by the 2010 Consensus Conference held in Honolulu.3

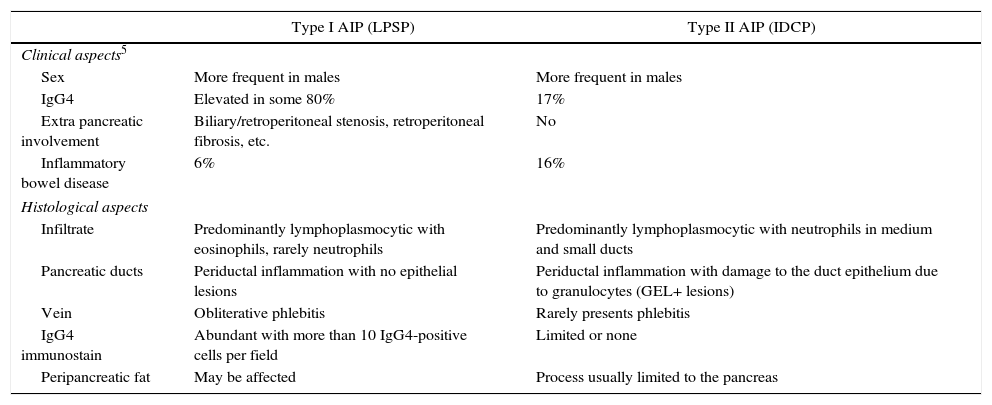

AIP is divided into 2 clinical-pathological forms: type I, or lymphoplasmocytic sclerosing pancreatitis (LPSP); and type II, or idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis (IDCP). The basic histological difference is the presence of infiltration by IgG4 cells over 10 cells/field in type I, which is very low or null in type II. Another important difference is the presence of granulocytic epithelial lesions in type II (GEL). Clinically, both types usually present as obstructive jaundice associated with a mass in the head of the pancreas (Table 1). It is therefore essential to perform a differential diagnosis with adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. According to Johns Hopkins Hospital data, the percentage of patients with AIP defined by the pathology study of a specimen from a resection due to suspected pancreatic adenocarcinoma is 2.4%.4

Histological Clinical Aspects of Type I and II AIP.

| Type I AIP (LPSP) | Type II AIP (IDCP) | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical aspects5 | ||

| Sex | More frequent in males | More frequent in males |

| IgG4 | Elevated in some 80% | 17% |

| Extra pancreatic involvement | Biliary/retroperitoneal stenosis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, etc. | No |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 6% | 16% |

| Histological aspects | ||

| Infiltrate | Predominantly lymphoplasmocytic with eosinophils, rarely neutrophils | Predominantly lymphoplasmocytic with neutrophils in medium and small ducts |

| Pancreatic ducts | Periductal inflammation with no epithelial lesions | Periductal inflammation with damage to the duct epithelium due to granulocytes (GEL+ lesions) |

| Vein | Obliterative phlebitis | Rarely presents phlebitis |

| IgG4 immunostain | Abundant with more than 10 IgG4-positive cells per field | Limited or none |

| Peripancreatic fat | May be affected | Process usually limited to the pancreas |

IDCP: idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis; LPSP: lymphoplasmocytic sclerosing pancreatitis; AIP: autoimmune pancreatitis.

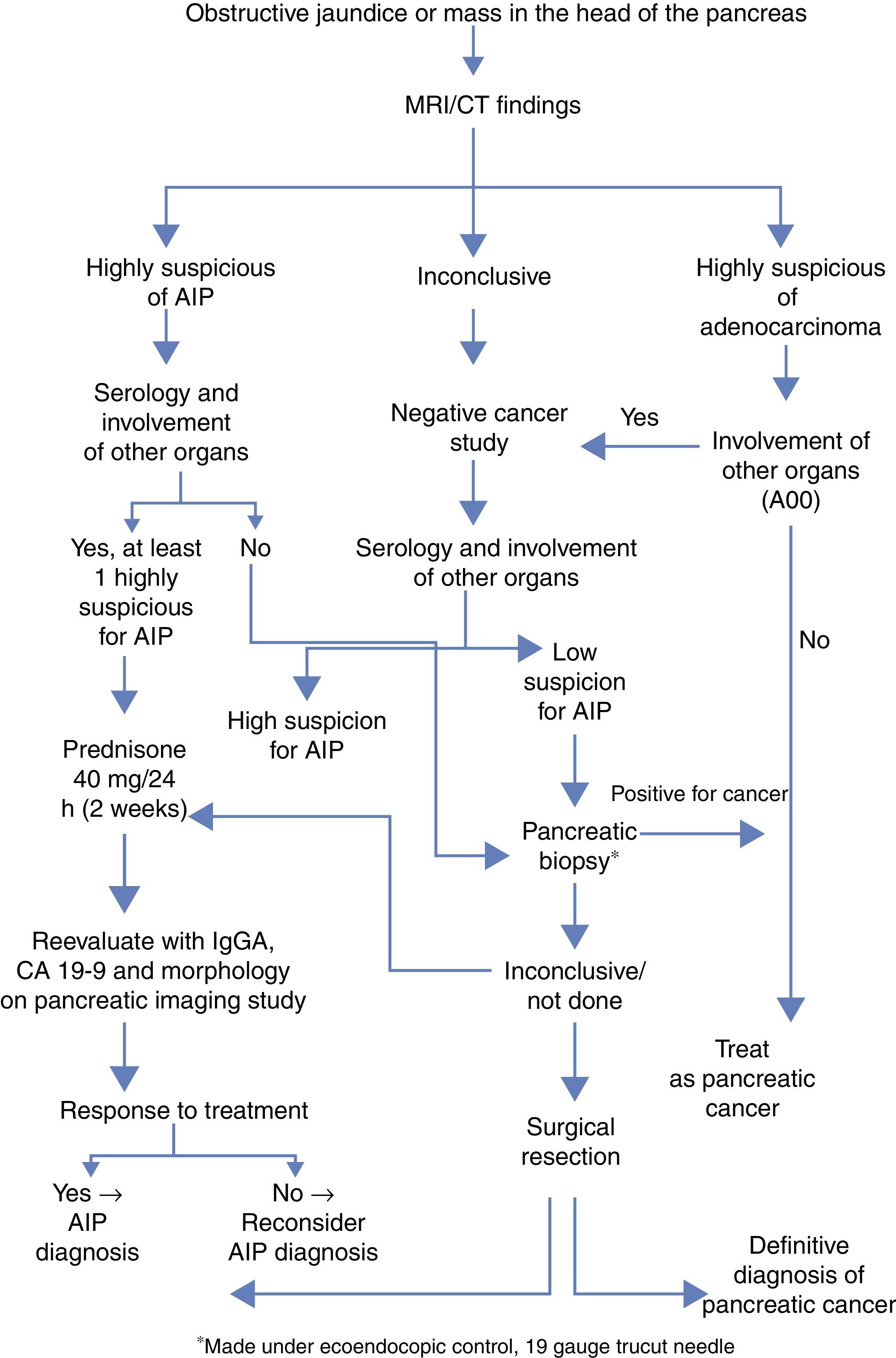

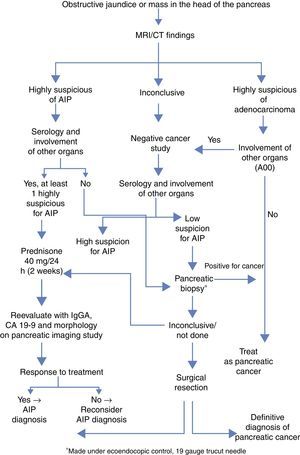

AIP is a disease that responds to treatment with corticosteroids, and accurate diagnosis is crucial to avoid unnecessary major surgeries. The diagnosis is based on five factors: histology, imaging, serology, involvement of other organs and response to corticoid treatment (HISORt criteria).6 Based on these criteria, the Mayo Clinic has proposed an algorithm to optimize the therapeutic diagnostic management of these patients (Fig. 1).

Simplified diagnostic algorithm by the Mayo Clinic to differentiate between adenocarcinoma of the pancreas vs AIP.4

Radiological characteristics can be a determining factor in the differential diagnosis. The complementary tests that best guide the definitive diagnosis are computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The characteristic findings of CT are diffuse sausage-like pancreatic thickening with peripheral hypoattenuation, as well as loss of lobe and involution of the tail. The criteria established by Sugumar et al.7 in the pancreatogram after ERCP are: elongated stenosis of the main duct (more than one-third of its length), absence of pre-stenotic dilatation (less than 5mm), multiple stenoses and branches from the main segmental stenosis.

Serum elevation of IgG4 (immunoglobulin G4) above normal levels (140mg/dL) is another of the basic diagnostic criteria. The Mayo Clinic group gives this criterion a sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value of 76%, 93% and 36%, respectively.8

Treatment with corticosteroids should only be initiated after adenocarcinoma has been ruled out. The recommended dose is 40mg of prednisone every 24 hours. After 2 weeks, the response to treatment should be evaluated with IgG4, Ca 19-9 and imaging tests. A dose of 5mg per week is maintained in cases with response, whereas in patients with no response (defined by the lack of radiological improvement), it is necessary to reconsider the diagnosis and even resort to surgery.

Below, we present our experience with this disease applying the algorithm proposed by the Mayo Clinic, with the exception that we do not have ultrasound-guided biopsy available, which we substituted with fine-needle aspiration (FNA).

Case 1A 46-year-old male was admitted due to jaundice associated with a mass in the head of the pancreas. Clinically, there was an increase in the number of daily stools with signs of steatorrhea. Lab work detected the following findings: total bilirubin 10.4mg/dL, GGT 673IU/L (gamma glutamyl transferase) and ALP 638IU/L (alkaline phosphatase), IgG 1410mg/dL (normal levels: 700–1600mg/dL) and Ca 19-9 38. CT scan demonstrated dilatation of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tract with a mass at the head of the pancreas. ERCP and endoscopic ultrasound identified a 35mm lesion causing stenosis of the main pancreatic duct. FNA showed glandular atypia of undetermined significance. As pancreatic adenocarcinoma was suspected, we performed pancreaticoduodenectomy. The definitive pathological diagnosis was compatible with autoimmune type I (lymphoplasmocytic sclerosing) pancreatitis.

Case 2The patient is a 57-year-old woman with a history of ulcerative colitis who presented with choluria, acholia and belt-like radiating abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed conjunctival jaundice. The biochemical profile showed: total bilirubin 9.1mg/dL, GGT 897IU/L, ALP 347IU/L. Tumor marker levels (CEA, Ca 19-9) and IgG4 were normal. CT scan and endoscopic ultrasound revealed a lesion in the head of the pancreas and uncinate process suggestive of adenocarcinoma versus neuroendocrine tumor, given the contrast uptake characteristics. FNA was not diagnostic, so the tumor committee decided on a surgical procedure. Pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed, enlarging the resection to total pancreatectomy since the intraoperative biopsy of the resection margin presented possible neuroendocrine tumor involvement. The definitive pathology diagnosis was type II EPI (idiopathic duct-centric).

Please cite this article as: Enjuto Martínez DT, Herrera Merino N, Pérez González M, Llorente Lázaro R, Castro Carbajo P. Pancreatitis autoinmune: diagnóstico diferencial con adenocarcinoma de páncreas. Cir Esp. 2017;95:480–482.