Injury to the lymphatic system, either by obstruction or by traumatic disruption, gives rise to leakage of lymphatic fluid that can accumulate in the thoracic and abdominal cavities.1 Chylothorax is the most common cause of pleural effusion in neonates, although in adults it represents only 3% of cases of pleural effusion. Chylous ascites is even less common, with an incidence of approximately 1 in every 20,000 cases. The simultaneous accumulation of lymph in the serous cavities is very rare. It is usually associated with non-traumatic etiologies2 and can lead to severe nutritional deficiency as well as immunosuppression that could lead to life-threatening situations for the patient.3

We present the case of a 38-year-old patient with no relevant personal history who started with an episode of progressive dyspnea associated with massive left pleural effusion compatible with chylothorax. Initially, he responded to conservative treatment with pleural drainage, nil pero os, and total parenteral nutrition. The extension study to determine its origin included a thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan that showed an incidental finding of a lesion in segment V of the liver. Liver segmentectomy was performed, and the pathology study reported benign hepatic adenoma. The immediate postoperative period was uneventful. However, 7 days after hospital discharge, the patient was readmitted due to predominantly left bilateral pleural effusion compatible with bilateral chylothorax. Since the discharge through the left drain was > 500 mL/day and taking into account the anatomical variations of the thoracic duct described in the bibliography,4 fluorescence-guided left video-assisted thoracoscopy and ligation of the thoracic duct were performed after administration of indocyanine green as a localization method. After surgery, the discharge of the left hemithorax decreased considerably; however, the right side increased to more than one liter a day, so it was decided to surgically address the right side, this time using lateral thoracotomy: the thoracic duct was located and tied at that level. As a result of this last intervention, the collected discharge from both thoracic drains fell significantly (<100 mL/day). Despite this, on the second postoperative day, the patient developed abdominal distension and pain along with oliguria and impaired renal function. Abdominal ultrasound revealed an abundant amount of free fluid that, after aspiration and drainage, again showed the presence of lymph.

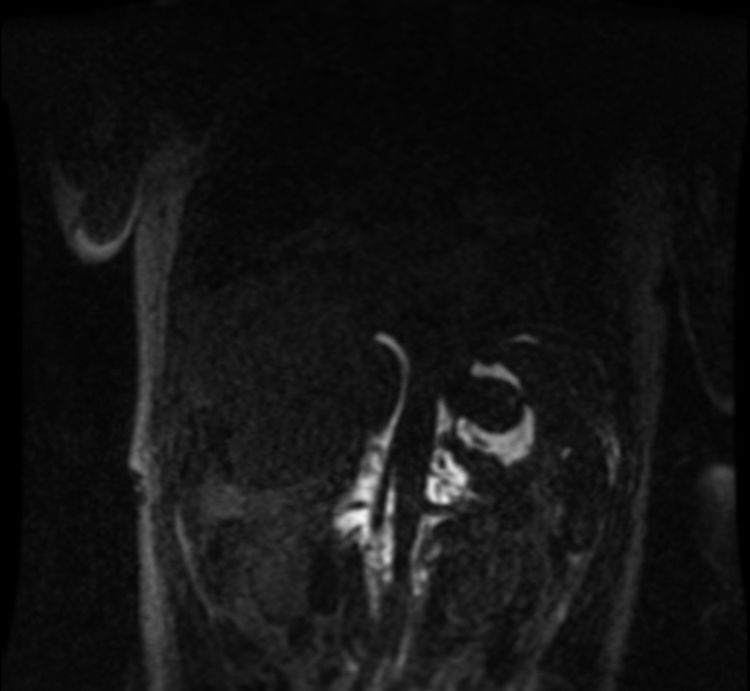

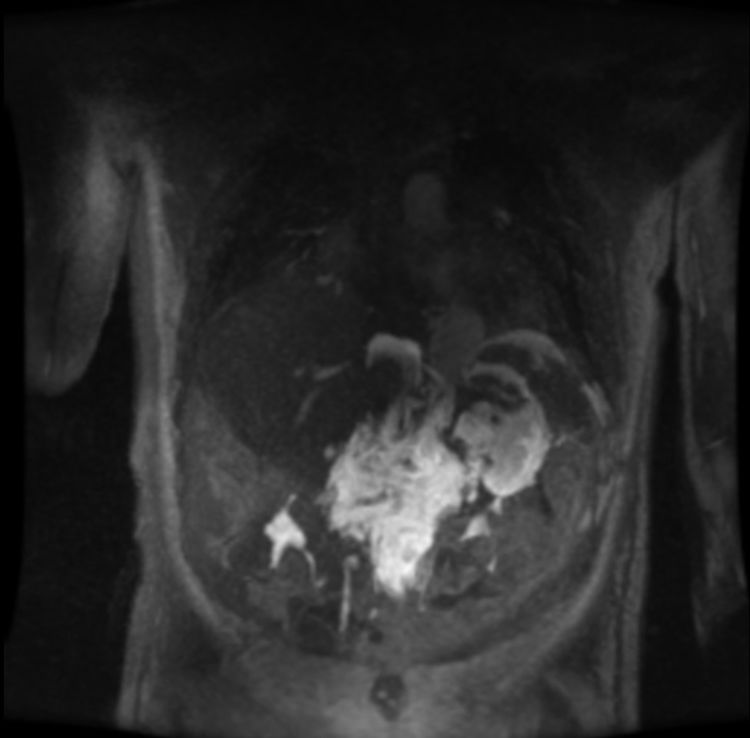

Once all the possible secondary medical etiologies potentially causing this condition had been ruled out, magnetic resonance lymphography was performed, which detected an abdominal mass with a craniocaudal diameter of 11 cm that had not been observed on the initial computed tomography scan. The lesion extended from the celiac vessels up to the renal hila surrounding the abdominal aorta in early phases (Fig. 1), with extravasation of the contrast agent into the abdominal cavity in late phases (Fig. 2).

The clinical-radiological diagnosis of bilateral chylothorax was established, in association with chylous ascites resulting from spontaneous rupture of a retroperitoneal lymphangioma.

Since the therapeutic options from the surgical point of view were limited and based on few clinical cases described in the literature,5 immunosuppressive treatment with sirolimus was initiated. The amount of discharge decreased, but not enough for withdrawal of the drainage tubes or to consider the condition resolved. Therefore, also based on references with low scientific evidence,1,3 we opted for low-dose adjuvant radiotherapy (10 Gy, 1 Gy/day) directed at the retroperitoneal mass. Afterwards, the patient progressed favorably, with progressive withdrawal of the drainage tubes 5 days after the end of radiotherapy treatment. Since discharge, the patient has maintained intermittent immunosuppressive treatment and a diet rich in medium-chain triglycerides, presenting no new episodes.

Lymphatic malformations are rare benign anomalies that result from defective embryonic development of the primary lymphatic structures, which generally present as dilations of the lymphatic vessels, creating multiple cysts that vary in size.4 Retroperitoneal lymphangiomas account for less than 1% of all lymphangiomas; they are usually asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally.6 The presentation as bilateral chylothorax or chylous ascites is extremely rare; there are published case reports of chylothorax7 or chylous ascites8 as an isolated manifestation of mediastinal-retroperitoneal lymphangiomas. However, the simultaneous presentation of both entities in a lymphangioma of retroperitoneal location alone has not been described previously. Magnetic resonance lymphography after intranodal administration (bilateral inguinal lymph nodes) of 50% gadolinium is the most appropriate technique for visualization and mapping of the lymphatic vascular system. In all cases, the therapeutic decision must be individualized and based on the type of malformation, size, location, and associated symptoms. Classically, surgery has been considered the treatment of choice, but resection is often incomplete and associated with high rates of recurrence. For this reason, less invasive therapeutic options have recently been described, such as sclerotherapy, laser treatment, radiotherapy and pharmacological treatment.1,5,9,10

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare, either directly or indirectly, with the content of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez Alvarado I, Gómez Hernández MT, Temprado Moreno V, Herráez García J, Jiménez López M. Quilotórax bilateral y ascitis quilosa como consecuencia de la rotura espontánea de un linfangioma retroperitoneal. Cir Esp. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2019.12.006