Breast lymphoma is a rare disease that represents 0.5% of malignant breast tumors.1 It can be primary when it occurs only in this location (including ipsilateral axillary lymph node chains) in the absence of previous extramammary or secondary disease when it is part of a varied involvement of extranodal lymphoid tissue. The breast is an uncommon site of appearance, observed in only 1.7%–2.2% of cases.1,2 The non-specific clinical and radiological characteristics of the tumor can be confused with a breast carcinoma, delaying correct treatment.3 We present a case of primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) of the breast that led to extensive necrosis of the breast and severe multiple-organ involvement, with descriptions of its special clinical and radiological features and reviewing the available literature on the subject.

A 57-year-old female patient from Peru, who had been diagnosed 2 years ago with T-cell NHL by biopsy of palpable axillary lymphadenopathies associated with inflammation in the right breast, treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP). One year later, she presented with worsening symptoms of breast skin lesions and lymphocytic infiltration. Therefore, 3 more polychemotherapy regimens (gemcitabine-cisplatin-dexamethasone, dexamethasone-cytarabine-cisplatin (DHAP) and hyper-CVAD-methotrexate-ARA-C) were administered, without a good response. The patient decided to seek treatment in Spain, where she was evaluated by the hematology service, observing cutaneous vesicles and yellowish crusts with increased pain and inflammation in the right breast that extended to the arm and abdomen. Initially, prednisone and hydroxyurea were administered, with no improvement, so the patient was hospitalized for further studies.

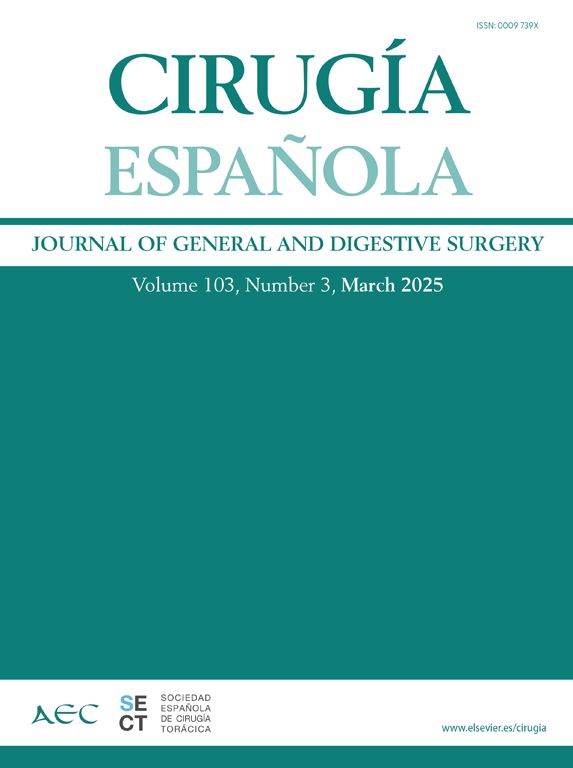

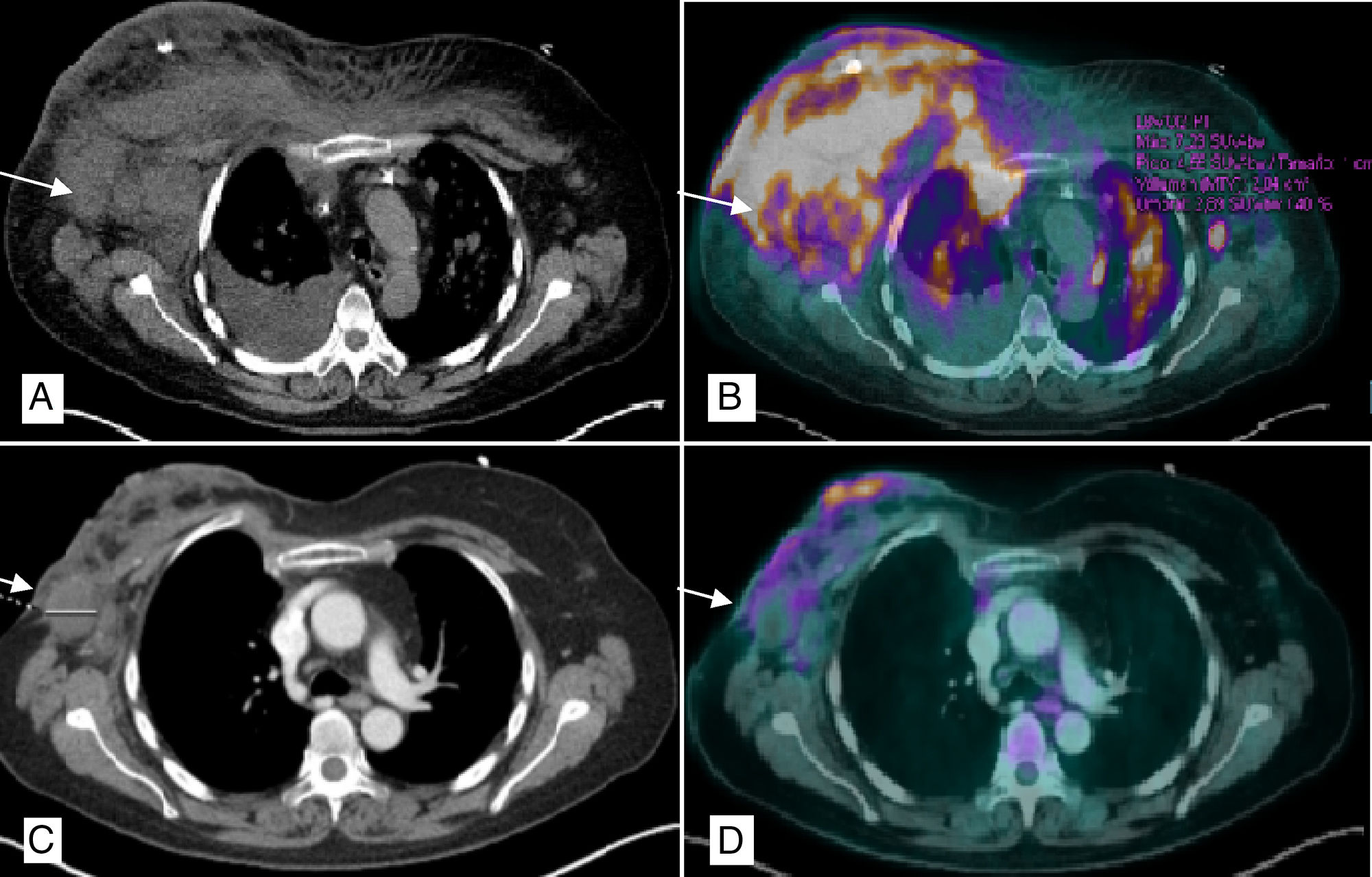

Biopsy of the breast lesions showed evidence of epidermal spongiosis and small cells with irregular nuclei, limited cytoplasm and predominant CD4 positivity compatible with CD30+ T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (HTLV−). PET/CT (Fig. 1A and B) demonstrated evidence of subcutaneous involvement in both breasts, multiple supra- and subdiaphragmatic, splenic and pulmonary lymphadenopathies related to the progressing lymphoproliferative syndrome. We decided to initiate palliative treatment (methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide, etoposide and procarbazine) with an excellent response, so we decided to discharge the patient until hematological recovery. Two months later, treatment was suspended due to febrile neutropenia and the patient came to the emergency department with superinfection of the breast tissue and complete necrosis of the breast (Fig. 2A).

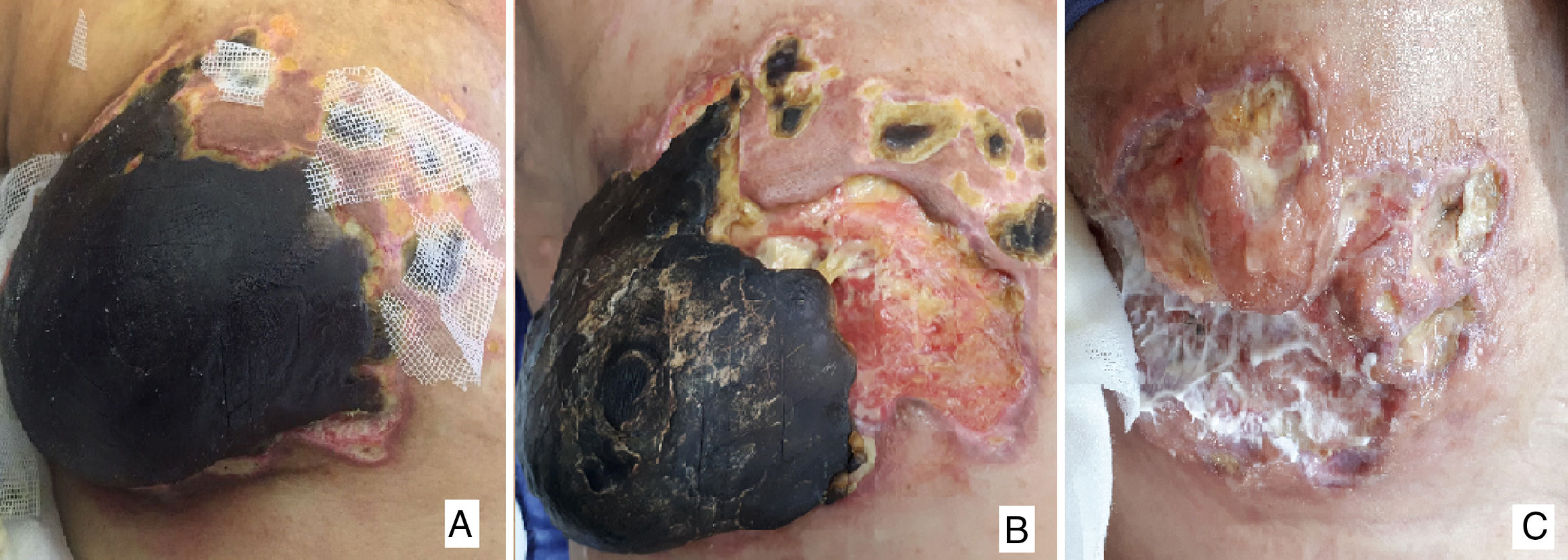

PET/CT chest scan: (A) Multiple bilateral axillary lymphadenopathies, the largest on the right measuring 4cm (arrow), with subcutaneous involvement of both breasts, predominantly right, and ipsilateral pleural effusion; (B) Pathological uptake of 18F-FDG (fludeoxyglucose) in the right breast, left breast, right lower sulcus and bilateral pulmonary parenchyma (millimeter nodules) related with the lymphomatous infiltration; (C) Decrease in the overall size of the right breast with air bubbles in its interior related with necrosis and reduction of axillary lymphadenopathies, the largest right measuring 2.9cm; (D) Morpho-metabolic improvement of the lymph node, pulmonary and subcutaneous cellular tissue involvement, suggestive of a good response to treatment.

(A) Complete right breast necrosis 2 months after the start of palliative treatment; (B) Surgery one month later: delimitation of the necrosis with almost complete detachment of the gland; (C) Fifteen days post-op, good evolution of the surgical wound with granulation tissue and absence of new lesions.

The patient was admitted and, after hematological recovery, the regimen was reinitiated, with radiological improvement (Fig. 1C and D) and delimitation of the necrosis, at which time it was decided to perform hygienic mastectomy to improve local control of symptoms. During surgery, almost complete detachment of the gland was observed, with a stony consistency due to the necrosis and purulent material inside (Fig. 2B). A simple mastectomy was conducted with partial pectoralis major and minor excision in areas that had been more affected by necrosis, while also eliminating several lesions in the sternal region. Immediate reconstruction was ruled out due to the infectious process and the difficult systemic control of the disease.

In the hospital ward, the patient continues with local treatment and good evolution (Fig. 2C). The definitive pathology study reported extensive necrotic breast parenchyma with calcifications, where no viable tumor could be identified. Currently, 2 months after surgery, the previous palliative treatment has been restarted with no new complications, and locally the wounds have healed adequately by second intention, although there is evidence of new malignant lesions in the thoracic dorsal region, so the prognosis is still unfavorable.

Breast lymphoma is a rare entity that occurs in women between 60 and 65 years of age, with bilateral involvement in only 11% of cases.4 Clinically, different presentations are observed, from a solid nodule to a diffuse thickening, either with or without lymphadenopathies; it most frequently (60% of cases) begins as a painful mass that is difficult to distinguish from a carcinoma, which can sometimes be ulcerated or present as Paget's disease of the nipple.5 The radiological diagnosis is not very specific, and ultrasound images mimic those of a carcinoma. Only on mammography could the absence of microcalcifications be a sign to distinguish it from other tumors. In addition, magnetic resonance imaging shows a single uptake focus or multiple hyperintense uptake foci in sequences with contrast, which would also not be specific for this type of tumors.6

The definitive diagnosis is obtained by core-needle biopsy or in the context of a conservative surgical resection, observing the presence of lymphoid-predominant neoplastic cells that varies according to the histologic type, the most frequent being diffuse large-cell NHL (60%–75%).5,7 The type of peripheral T-cell NHL in our case is a less common type of tumor that is associated with human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV), especially in Eastern and Caribbean countries. The overexpression of CD30 is even rarer, being a factor for better prognosis compared to individuals who do not present it.7,8 With greater aggressiveness and an average survival of 4 years, in these cases early diagnosis is fundamental for the choice of adequate treatment.9

Depending on the stage of the disease, we can opt for an excisional biopsy, associated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy (low-grade initial stages) or systemic treatment with polychemotherapy (advanced high-grade stages), leaving surgery limited to cases that require local control of symptoms.5,10 Mastectomy does not offer any benefits compared to conservative surgery, while the axilla stage is prognostic and fundamental for the choice of radiotherapy or subsequent chemotherapy.5,10,11 When presented as a complicated mass, as in our case, mastectomy would be indicated to reduce pain, infection and tumor burden, offering a deferred reconstruction technique when systemic control of the disease is established, preferably with the use of autologous tissue.10,12

The CHOP regimen, either with or without rituximab, is the most widely used polychemotherapy offering the best results. Later, it is associated with radiotherapy, and both factors decrease local relapse rates.1,11 Regarding the prognosis, there are known factors that determine the risk of recurrence. High-risk patients are those over the age of 60, with a worse baseline general state, who have disease in 2 or more extranodal sites and present advanced-stage disease at the onset.3

Although the special characteristics of these tumors are well known, their location in the breast is uncommon. The refractoriness to treatment, histological type and serious sequelae observed in the breast of our patient make this case special and not previously reported in the literature. Although treatment in breast lymphoma is similar to treatment for other locations, there are still controversies about the role of surgery and larger series will determine whether its use is necessary or should be left only for exceptional cases.

Please cite this article as: Tejera Hernández AA, Gómez Ramírez J, Rivas Fidalgo S, Sánchez de Molina Ramperez ML, Díaz Miguel M. Necrosis mamaria en paciente con linfoma no Hodgkin primario de células T. Cir Esp. 2018;96:387–390.