Surgical wound infections after thyroid surgery have a low associated mortality rate.1 Among the microorganisms involved, group A Streptococcus is potentially lethal as it can be accompanied by descending necrotizing mediastinitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS). We present the case of a woman with no risk factors who had undergone thyroidectomy due to benign pathology and developed a lethal infection of the surgical wound due to group A Streptococcus.

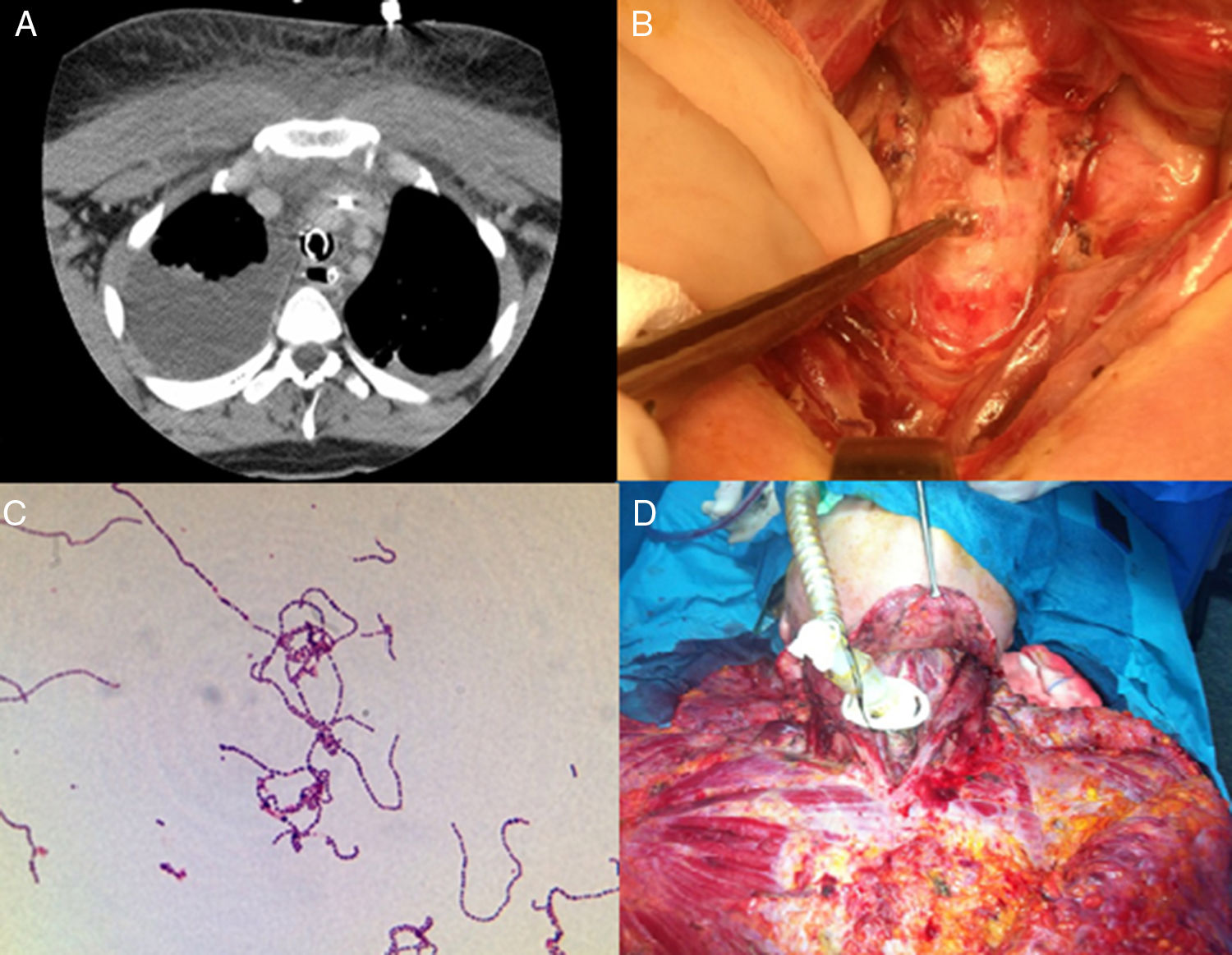

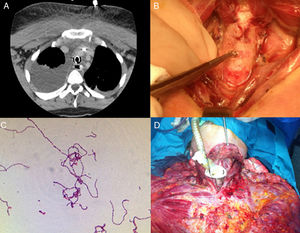

A 37-year-old woman with no relevant medical history consulted for asymptomatic multinodular goiter. Ultrasound revealed a multinodular goiter with a 3-cm right thyroid nodule in the lower pole. The FNA cytology was classified as Bethesda IV. Due to the tumor size and the aspiration sample, total thyroidectomy was performed. After 24h, the patient began with cervical pain and restlessness, later associating drowsiness and respiratory distress. Lab work was normal except for leukopenia 3.6×103/mm3 and O2 saturation of 76%. Given this situation, she was transferred to the intensive care unit. A CT scan (Fig. 1A) demonstrated severe right pleural effusion, bibasilar atelectasis and soft tissue edema in the superior mediastinum; a chest tube was inserted and purulent fluid was drained. With these findings, a revision procedure was performed in the operating room, which revealed tissue hypoperfusion, edema and tracheal perforation (Fig. 1B). Extensive cervical and thoracic surgical debridement was conducted with complete excision of tissue necrosis, decortication and pleural drainage. A tracheostomy was also performed due to the tracheal perforation and a culture was taken of the purulent fluid, compatible with group A Streptococcus (Fig. 1C). Because of the severity of the infection, the patient required support measures with mechanical ventilation, vasoactive substances and intravenous clindamycin. The patient was reviewed in the operating room 2 more times every 6h (Fig. 1D) by a team of thoracic surgeons, otolaryngologists and endocrine surgeons. The patient died 36h after the onset of symptoms. The final pathology study reported multinodular goiter.

(A) Right pleural effusion with bilateral atelectasis with involvement of the soft tissue of the superior mediastinum; (B) presence of tissue hypoperfusion, edema and involvement of the trachea during the first surgical debridement; (C) microbiological diagnosis of group A Streptococcus; (D) intraoperative findings of extensive involvement of the superior and inferior mediastinum during the last surgical debridement.

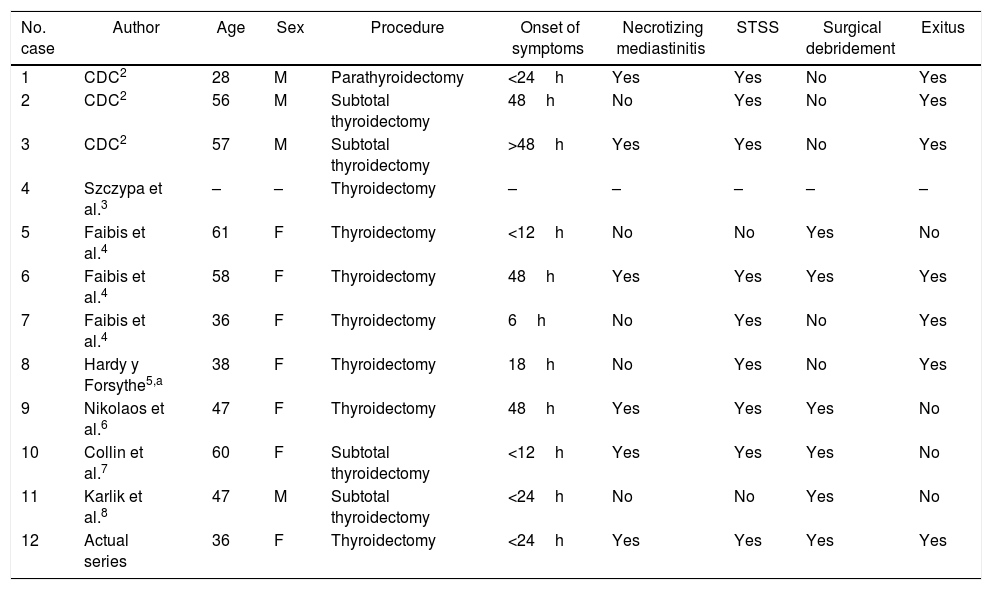

Infection after thyroid surgery is usually subacute, locoregional and self-limiting. In some cases of infection caused by group A Streptococcus (Table 1),2–8 the onset of symptoms may be sudden with nonspecific symptoms associated with a rapid evolution and important systemic involvement.

Characteristics of the Cases of Surgical Site Infection by Group A Streptococcus After Thyroid Surgery Reported in the Literature.

| No. case | Author | Age | Sex | Procedure | Onset of symptoms | Necrotizing mediastinitis | STSS | Surgical debridement | Exitus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CDC2 | 28 | M | Parathyroidectomy | <24h | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 2 | CDC2 | 56 | M | Subtotal thyroidectomy | 48h | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 3 | CDC2 | 57 | M | Subtotal thyroidectomy | >48h | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 4 | Szczypa et al.3 | – | – | Thyroidectomy | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5 | Faibis et al.4 | 61 | F | Thyroidectomy | <12h | No | No | Yes | No |

| 6 | Faibis et al.4 | 58 | F | Thyroidectomy | 48h | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Faibis et al.4 | 36 | F | Thyroidectomy | 6h | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 8 | Hardy y Forsythe5,a | 38 | F | Thyroidectomy | 18h | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 9 | Nikolaos et al.6 | 47 | F | Thyroidectomy | 48h | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 10 | Collin et al.7 | 60 | F | Subtotal thyroidectomy | <12h | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 11 | Karlik et al.8 | 47 | M | Subtotal thyroidectomy | <24h | No | No | Yes | No |

| 12 | Actual series | 36 | F | Thyroidectomy | <24h | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

F: female; STSS: streptococcal toxic shock syndrome; M: male.

Group A Streptococcus frequently colonizes the skin, pharynx, vagina and anus, and the asymptomatic colonization rate in adults varies from 2 to 8%.9 It commonly affects young and healthy patients where the source of infection is often unknown. Surgical incisions, foreign bodies, non-penetrating trauma and the use of NSAIDs are the most frequently associated factors. In the most severe cases with associated necrotizing fasciitis, the most common comorbidity is diabetes mellitus, while fulminant cases are rare in young patients with no risk factors such as the one presented here. Thyroid infections due to Streptococcus may present as a superficial infection, but they occasionally progress aggressively, associating extensive soft tissue necrosis, which, due to its location, affects the retropharyngeal, pretracheal and retroesophageal regions, triggering descending necrotizing mediastinitis. In this fulminant form of the disease, STSS may appear, where the patient is in a critical condition with associated fever, hypotension, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, metabolic acidosis, skin eruption, severe myalgia, renal failure, elevation of liver enzymes or bilirubin and neurological changes.10

For the definitive diagnosis, it is important to carry out a microbiological study before administering antibiotics. Laboratory results are usually nonspecific and imaging tests can help especially in doubtful cases, but these should never delay surgery in cases with high clinical suspicion.

Early therapy is the key to treatment. This involves proper management of fluid therapy, antibiotic treatment, renal and respiratory support and surgical treatment. Any invasive infection by group A Streptococcus should be treated with high doses of penicillin and clindamycin. Even so, the optimal approach is not clearly defined. Some groups recommend cervical drainage only if there is no involvement below the carina on the CT scan, associating cervical thoracostomy with a drain tube. Meanwhile, other authors, similar to us, recommend being very aggressive and performing open thoracotomy.7 Intravenous immunoglobulin is not used in a standardized manner because the timing of administration is critical and only offers short-term protection.

Few cases have been described in the literature with group A Streptococcus infection after thyroid surgery. Upon analyzing these (Table 1), we have observed that all deaths were associated with STSS and that in all but one surgical debridement was not performed. On the other hand, all patients who survived this condition also had extensive debridement.

Therefore, although descending necrotizing mediastinitis with STSS due to group A Streptococcus after thyroid surgery is a rare condition, it has a high associated mortality rate. Therefore, in the presence of a high level of suspicion, early diagnosis is essential, followed by aggressive surgical treatment and the application of support measures.

Please cite this article as: López-López V, Ríos Zambudio A, Rodríguez González JM, Segura Rodriguez J, Parrilla P. Infección letal por Streptococcus del grupo A en cirugía tiroidea: la importancia de un diagnóstico precoz. Cir Esp. 2018;96:385–387.