Extended thymectomy is superior to conventional thymectomy as it eliminates all tissue containing thymic remains, which could be responsible for the lack of remission after surgery.1,2 Another reason to consider thymectomy in the treatment of this disease is the real possibility that myasthenic symptoms could be related with a thymoma, even when tomography shows a thymus with morphologically normal characteristics.

In this article, we describe how we conduct “butterfly wing” extended thymectomy for the surgical treatment of myasthenia gravis.

The indications for surgical treatment were based on the following criteria3: resistance to pyridostigmine or immunosuppressant treatment, generalised myasthenia with no improvement after 6 months of medical treatment, ocular myasthenia with partial response to pyridostigmine and lack of stable, complete remission for a period of more than 2 years. Prior to surgery, all patients received treatment with Intacglobin® 400mg/kg, which was administered in 5 doses (3 pre- and 2 postoperative). This technique was performed by the same surgeon.

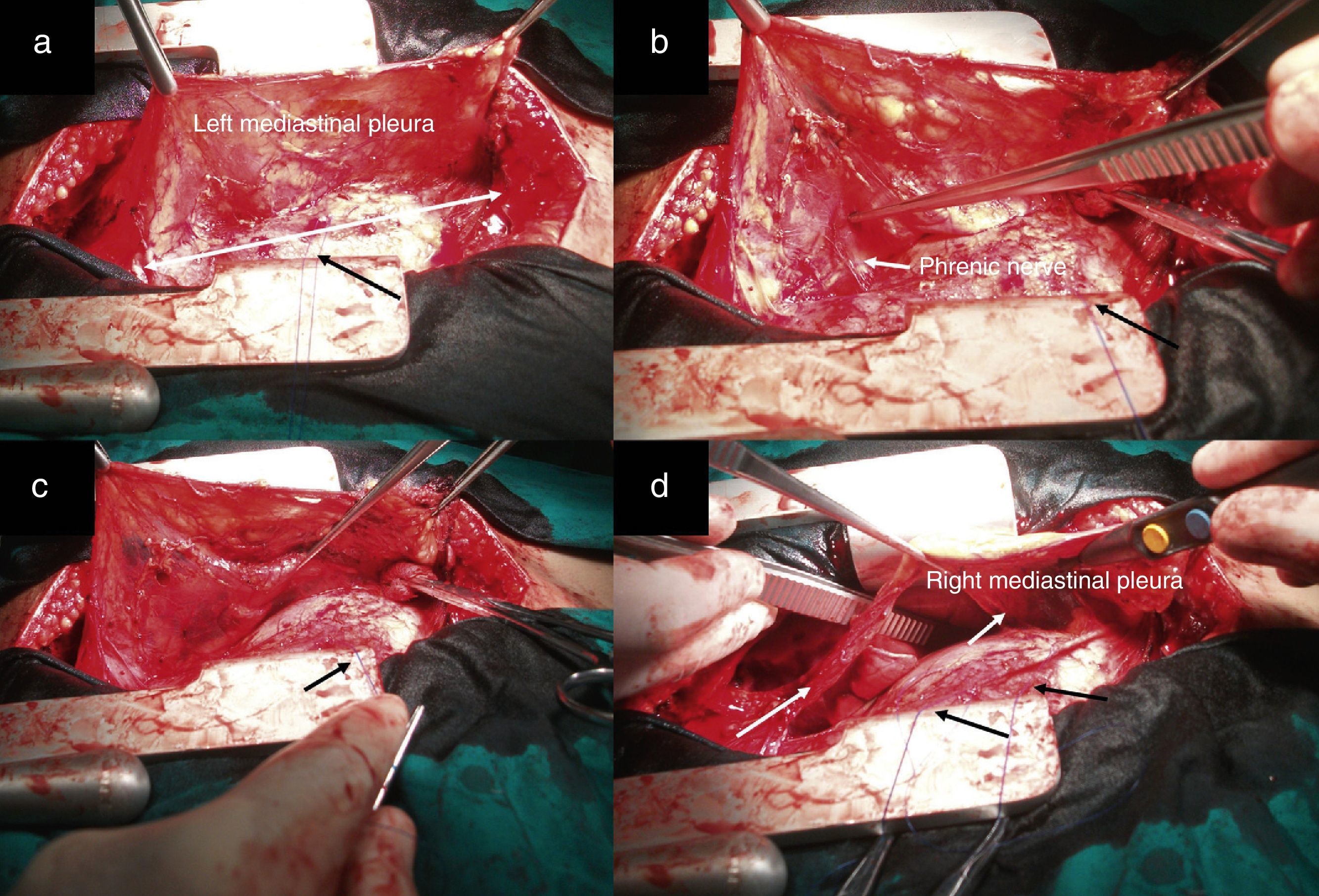

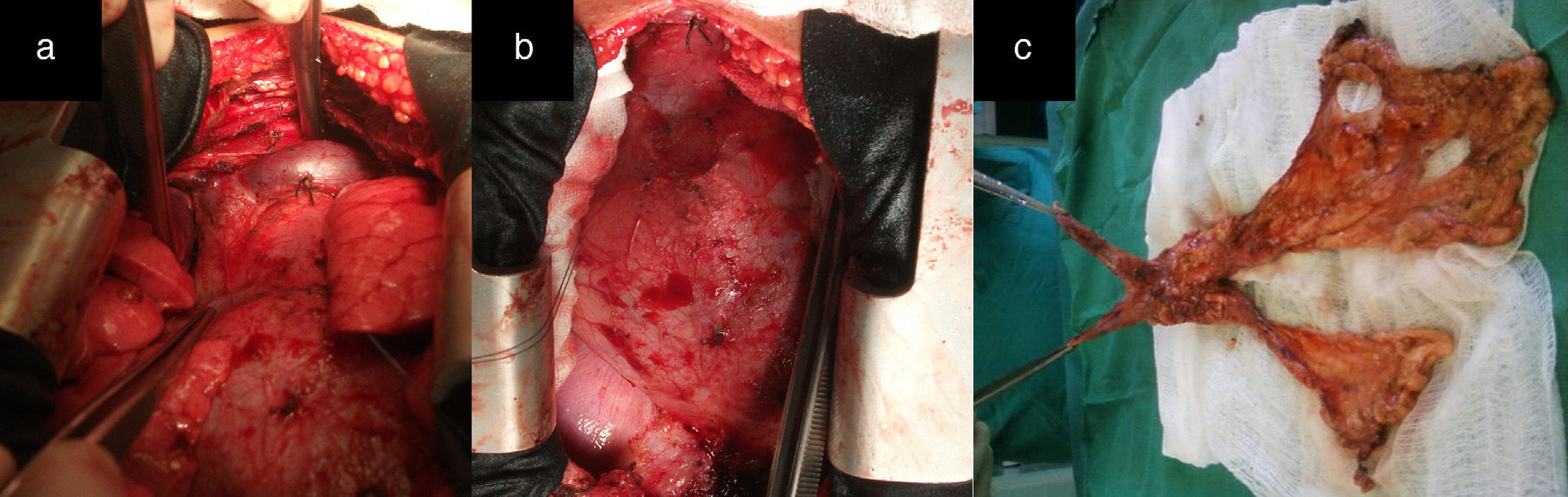

After median sternotomy, both pleurae were opened just under the lower end of the sternum, from the manubrium to the xiphoid process. We then began the dissection of both mediastinal pleurae and adhered fatty tissue. The way in which we carried out this dissection is the first modification of the traditional technique radical en bloc resection. For this, we used as a reference a longitudinal line from the base of the thymus to the diaphragm, as shown by the white arrow in Fig. 1a, where we initiated the dissection and resection of both pleurae. In this manner, we first dissected the left pleura to the phrenic nerve laterally and to the diaphragm underneath (Fig. 1b and c). The black arrows show the second modification of the traditional technique, involving the placement of sutures through the pericardium to then pull on them gently and facilitate the distal approach of the mediastinal pleura and accompanying fat, especially as we approach the phrenic nerve and diaphragm, which are areas with the most difficult access. This provided a better approach as we moved away from the midline. We then proceeded in the same manner with the right mediastinal pleura (Fig. 1d, see white arrows). Afterwards, both pleurae were dissected underneath from the diaphragm, laterally 1cm above the phrenic nerve, turning to resect the largest possible quantity of fat, especially at the aortopulmonary window. The thymic vessels coming from the internal thoracic artery were ligated, and both dissected pleurae were placed outside the surgical field for the approach of the thymic veins. We then proceeded to mobilise the thymus, separating it from the brachiocephalic venous trunk and ligating the venous branches that drained into it. The fat occupying this region and the extrapericardial aortocaval space was also resected. We completed the dissection of the thymus and replaced all the resected tissue (over the pericardium), dissected the horns of the thymus and the accompanying fat from above the thyroid (respecting the parathyroid), the carotid arteries laterally and the trachea posteriorly. The branches coming from the inferior thyroid artery were ligated, concluding the complete resection of the thymus and all the fat that could include thymic remains and occupied the region between the thyroid above, the diaphragm below and both phrenic nerves laterally (Fig. 2a and b). Fig. 2c demonstrates the butterfly wing shape of the thymus and both mediastinal pleura with the accompanying fat when they were totally resected with this surgical technique.

Image showing the dissection of both mediastinal pleurae with the accompanying fat in two sections (right and left). The black arrows of all the figures represent the anchoring points in the pericardium. (a) The white line represents a longitudinal line from the base of the thymus to the diaphragm, which was taken as a reference to initiate dissection; (b and c) image showing the utilisation of the pericardial retractors for the dissection of the mediastinal pleura in the diaphragm region. The white arrow indicates the left phrenic nerve and (d) the white arrows indicate the dissected right mediastinal pleura.

(a and b) Image showing how the entire region from the thyroid above, the diaphragm below, and both phrenic nerves laterally are free of fatty tissue that could contain thymic remains. (c) The butterfly wing-shaped surgical specimen of the thymus and both mediastinal pleurae with accompanying fatty tissue after complete resection with this surgical technique.

Twenty-two patients were operated on with juvenile myasthenia gravis and a histological diagnosis of thymic hyperplasia. With a mean follow-up of 60.95 months (minimum 13 and maximum 145 months), 16 patients are treatment-free and 5 require less medication to control their myasthenic symptoms. No myasthenic crises occurred in the postoperative period. There were no deaths. One patient presented left pleural effusion that was evacuated by needle aspiration.

Extended radical thymectomy done in 2 blocs with the modifications that we have described in this article does not significantly differ from traditional en bloc extended thymectomy.1–5 It does, however, facilitate first of all the dissection of both mediastinal pleurae with the accompanying fat, especially in the regions near the diaphragm and in the aortopulmonary window, which are areas that are more difficult to access. Second, it provides a safer approach and dissection of the regions close to the phrenic nerves. Another advantage of this technique is that it facilitates the approach of the thymus while following the premise that the first step for the manipulation of the thymus should be only what is necessary for the dissection and ligature of the thymic veins, which thus avoids the dissemination of thymic humoral factors that could lead to a myasthenic crisis in the postoperative period.3 In spite of reports demonstrating the effectiveness of video-assisted extended thymectomy, there is still no consensus about which is the best approach for radical thymectomy.2,6–9 In conclusion, we want to emphasise that this two-part technique, starting from the midline region of the pericardium towards the diaphragm and laterally under the phrenic nerve, instead of in one single bloc, is equally effective for the surgical treatment of myasthenia gravis.

Please cite this article as: Vázquez-Roque FJ, Hernández-Oliver MO, Castillo-Vitlloch A, Rivero-Valerón D. Timectomía transesternal ampliada en forma de alas de mariposa. Cir Esp. 2016;94:186–188.