Catamenial pneumothorax (CP) is pneumothorax that occurs 3 days before or after menstruation.1 It is the most frequent manifestation of intrathoracic endometriosis, as described by Maurer in 1958.2 There are several theories about its etiopathogenesis and treatments, which have provided varying results. We present four cases of CP.

Patient 1 is 31 years old and presented with chest pain, dyspnea and a right hemothorax. She had a history of previous episodes of pneumothorax: episode 1 was treated with drainage; episode 2 was treated with the resection of apical bullae and abrasive pleurodesis by video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS); and in the third episode a chest drain was used. The presentation always coincided with menstruation and the patient also reported fertility problems. Surgery was proposed, and anaxillary thoracotomy was performed with decortication of the upper parietal pleura and abrasion pleurodesis. After surgery, the patient received hormone therapy. During a 5-year follow-up, she has had no recurrence of the pneumothorax and has carried a pregnancy to full term.

Patient 2 is 35 years old with a history of 3 episodes of right pneumothorax. She experienced menstrual pain and dyspnea as well as infertility due to endometriosis. VATS surgery included resection of right apical bullas and abrasion pleurodesis. One month later, she presented right recurrence. Axillary thoracotomy and parietal pleural decortication were performed, demonstrating pleural endometrial tissue. After surgery and hormone treatment, the patient did not present another pneumothorax and was able to carry a pregnancy to term. Three years after surgery, she presented partial left pneumothorax treated with chest drainage and suction. Five months later, she has presented no recurrences.

Patient 3 is a 40-year-old woman who was hospitalized with right pneumothorax that had been demonstrated radiologically on 2 occasions, along with dysmenorrhea, dyspnea and occasional chest pain during the menstrual period. Right apical bullae were resected with partial parietal decortication by VATS, which demonstrated pleural endometriosis. One month later, she presented basal lamina pneumothorax, which was treated without drainage and has presented no recurrence in 6 months.

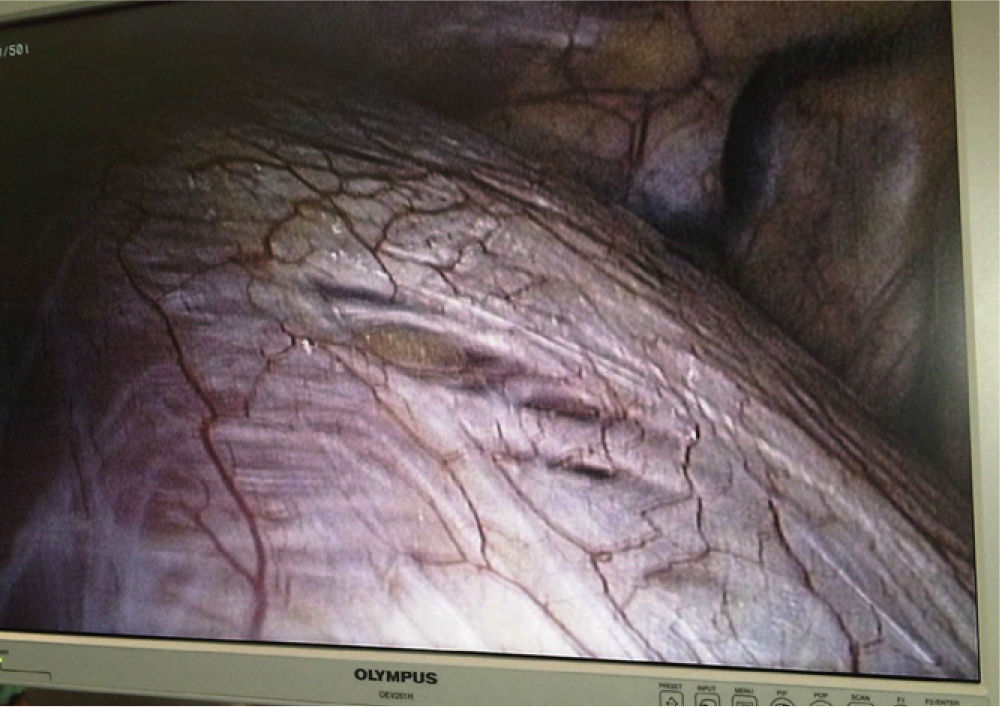

Patient 4 is 35 years old and has had 4 menstrual episodes of right pneumothorax, two of which were treated with drainage. Right apical bullae were resected, followed by VATS abrasion pleurodesis and chemical pleurodesis with talc. Intraoperatively, 3 orifices were observed in the diaphragm, which were no larger than 10mm (Fig. 1). Four months later, she has had no recurrence.

Approximately 61% of the patients with CP present signs of pelvic endometriosis.3 The average age is 32–37.3 The prevalence of CP is from 1 to 5% in women who present menstrual pneumothorax.4 The usual presentation is pain and dyspnea, most frequently on the right side.

There are several theories about the physiopathology of CP. Congenital diaphragm orifices are most frequent on the right side, so the thought is that endometrial tissue could migrate through the peritoneum from the uterus and enter into the thorax through these orifices. There are many publications that demonstrate this,5 and in our review of cases, case 4 had such orifices.

The hormonal theory by Rossi6 proposes that high levels of prostaglandin F2 produced during ovulation could cause vasospasms that trigger a pulmonary ischemic process that would lead to alveolar rupture, and therefore CP. This would explain why in some patients no diaphragm orifices or visible endometrial implants were able to be identified despite having been surgically evaluated. In contrast with this theory is the fact that prostaglandin inhibitors have failed as an effective treatment for CP.7 What supports this theory is that some patients improve when treated with drugs that inhibit ovulation and therefore reduce circulating prostaglandin levels.8

Another theory has to do with the anatomical changes of the cervix caused by menstruation. During the menstrual period, the cervix opens to allow the endometrial tissue to flow out, which pulls away and diminishes the mucus layer that protects against the entry of external agents, including the outer air, which could use this pathway into the uterus and pass through the Fallopian tubes to the abdomen and through the diaphragm orifices to the thorax. This would explain why some patients with CP present pneumoperitoneum.9 Treatments such as tubal ligation have been proposed to impede the retrograde passage of air and tissue.10 Evidence against this is that there have been some cases of CP after hysterectomy.11

As the theories of the etiogenesis are varied, so are the therapeutic options12:

- (a)

If there are visible bullae, these should be resected.

- (b)

If there is tissue suspicious of being ectopic endometrium, this should be resected together with decortication of the parietal pleura as extensively as possible in order to eliminate microscopic implants.

- (c)

If diaphragmatic fenestrations are observed, these should be repaired or sealed.

Other surgical alternatives, such as tubal ligation, hysterectomy, oophorectomy or mesh placement in the orifices of the diaphragm,13 should be used with caution. Hormone therapy after surgery is not only effective in the prevention of CP recurrence, but also in other patient problems, such as infertility. In our series, two cases were infertile and, after surgery and hormone replacement therapy, they were able to carry pregnancies to term.

In summary, CP is a syndrome with uncertain etiology that requires detailed patient information as well as radiological studies of the pneumothorax. Surgical treatment is always necessary and the type of intervention depends on the intraoperative findings.

Please cite this article as: Mier Odiozola JM, Fibla Alfara Molins L JJ, Molins López-Rodó L. Neumotórax catamenial: un síndrome heterogéneo. Cir Esp. 2014;92:366–368.