Ciliated hepatic foregut cysts (CHFC) are an uncommon pathology. While their histopathologic characteristics are pathognomonic, these lesions are clinically and radiologically indistinguishable from hepatic cystic neoplasms. Their potential for malignization requires surgical resection, so CHFC should always be included in the differential diagnosis of hepatic lesions.1–4

We report the case of a patient with colorectal cancer (CRC) and a single synchronous hepatic lesion that was suspicious for metastasis, treated by simultaneous laparoscopic resection of the sigma and liver. The hepatectomy specimen was compatible with CHFC.

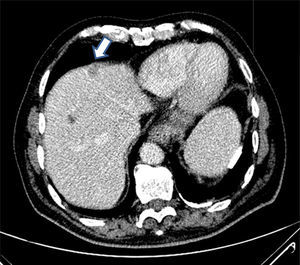

The patient is an 82-year-old male with no prior medical history of interest and a recently diagnosed adenocarcinoma of the sigma. Thoracoabdominal extension computed tomography (CT) scan showed evidence of a simple cyst in liver segment VIII and an enhanced solid lesion measuring 16mm in segment IV that was suggestive of metastasis (Fig. 1).

In this context of a patient with CRC and resectable solitary synchronous hepatic metastasis, a multidisciplinary committee decided to conduct a combined laparoscopic resection of the sigmoid and hepatic lesions.

After having completed the laparoscopic sigmoidectomy without incident, laparoscopic hepatic ultrasound was done. We identified the simple cyst in segment VIII as well as a 15mm lesion in segment IV that was hypoechoic and cystic, whose content presented different echogenicity than the simple cyst. No other lesions were identified.

Ultrasound-guided laparoscopic partial hepatectomy was completed without incident. When the surgical specimen was opened, we observed a cystic lesion with a gray mucoid content and wide resection margins. The patient was discharged on the seventh day post-op.

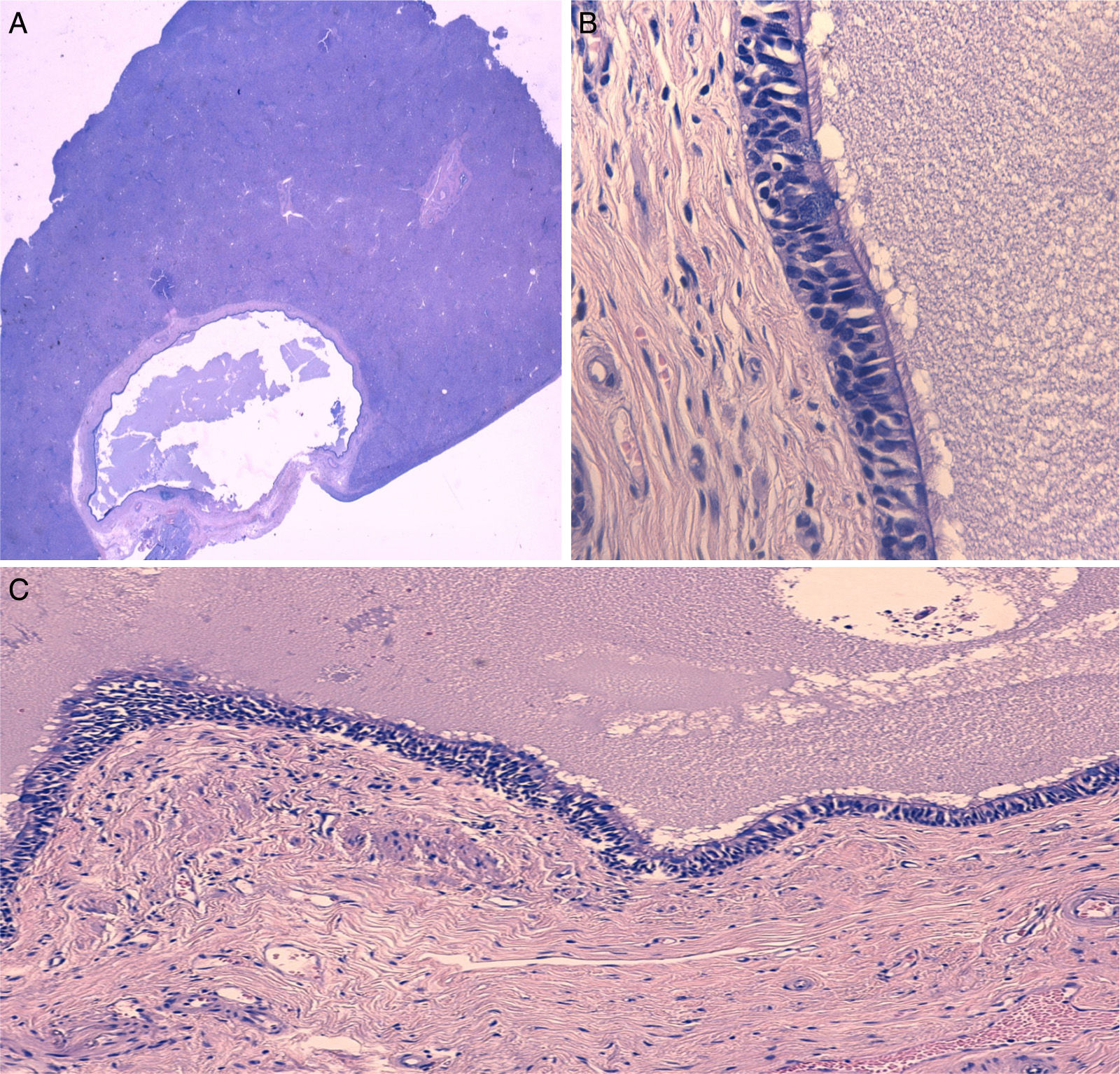

The pathology study described a cystic structure covered in pseudostratified epithelium of a respiratory type, with cilia and isolated goblet cells. In the periphery of the nodule, fibrosis was observed with a proliferation of reactive pattern duct elements, all of which were compatible with CHFC (Fig. 2).

(A) Microscopic image of QHC surrounded by normal liver parenchyma (hematoxylin-eosin), (B) Detail of the cyst wall showing the pseudostratified ciliated epithelium and the underlying smooth muscle layer (hematoxylin-eosin ×400), and (C) Detail of the cyst wall showing the pseudostratified ciliated epithelium and the characteristic underlying layers (hematoxylin-eosin ×100).

CHFC are rare lesions, with no more than 100 published cases, although their incidence is growing, probably due to the improved quality of diagnostic techniques.5

In most cases, CHFC present as solitary subcapsular lesions that are small in size (mean diameter 4cm) and located in the center of the liver, mainly in segment IV (although other sites have been reported in the literature5,6). This location could be explained by the fact that, during early embryonic development, bronchial remains from the proximal intestine could become trapped in the liver (derived from the caudal intestine).1

CHFC usually present in middle-aged patients. They are generally asymptomatic or associated with some abdominal discomfort, probably due to their location, which causes distension in Glisson's capsule.5 In adults, large-sized lesions can cause symptoms of compression and portal hypertension.7

The definitive radiologic diagnosis is not simple due to the variability in the appearance of CHFC (which seems to be attributed to the variable content of the cyst), so combined imaging studies are recommended in order to increase their diagnostic precision.5

On ultrasound, even though they may present a solid appearance, CHFC are usually seen as unilocular, hypoechoic cystic lesions.2 On baseline CT, they are hypodense lesions that do not uptake contrast, and in up to one-third of cases they can present as solid-looking lesions,3 as occurred in our patient. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), they are hyperintense in T2, while in T1 they present varying densities.

Cytology studies of samples obtained by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) can be useful to confirm the diagnosis with a positive predictive value of 76%.5 The histology of CHFC is pathognomonic, as its wall is comprised of 4 perfectly defined layers: (1) ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium, (2) connective tissue, (3) smooth muscle, and (4) fibrous tissue.1,5

From an immunohistochemical standpoint, these lesions express general and specific markers of foregut structures (cytokeratin 7 or 19), while the most specific markers of the caudal intestine are generally negative. Most cases express thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).8

CHFC are usually benign, although malignization has been described in 3%–5% of cases in the form of squamous cell carcinoma, mainly in larger lesions, with poor survival results.4 Therefore, the treatment of choice of these lesions is surgery.5 As other authors have demonstrated9 and as occurred in our case, the laparoscopic approach is a feasible option and recommendable due to the small size of these lesions as well as their central hepatic and subcapsular location. We should emphasize that, although the location and size of the lesion detected in our patient was characteristic of CHFC, the finding of a solid hepatic lesion in the context of colorectal oncologic disease required a differential diagnosis with metastasis since 15%–25% of patients with CRC present synchronous metastases.10 Complementary diagnostic tests (MRI, PET or FNA) could have fine-tuned the diagnosis, although the surgical indication for resection would have prevailed in any event.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: de la Serna S, García-Botella A, Fernández-Aceñero M-J, Esteban F, Diez-Valladares L-I. Quiste ciliado hepático, diagnóstico diferencial de lesiones hepáticas del segmento iv. Cir Esp. 2016;94:545–547.