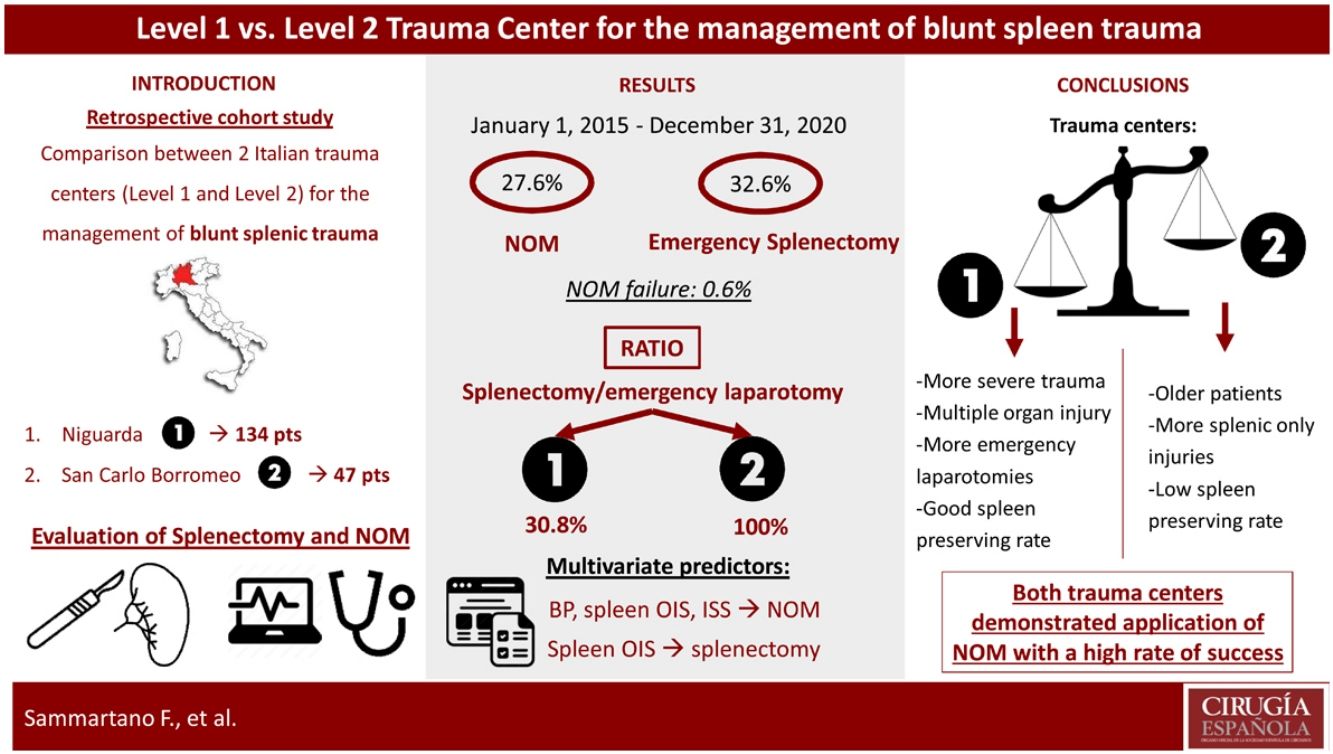

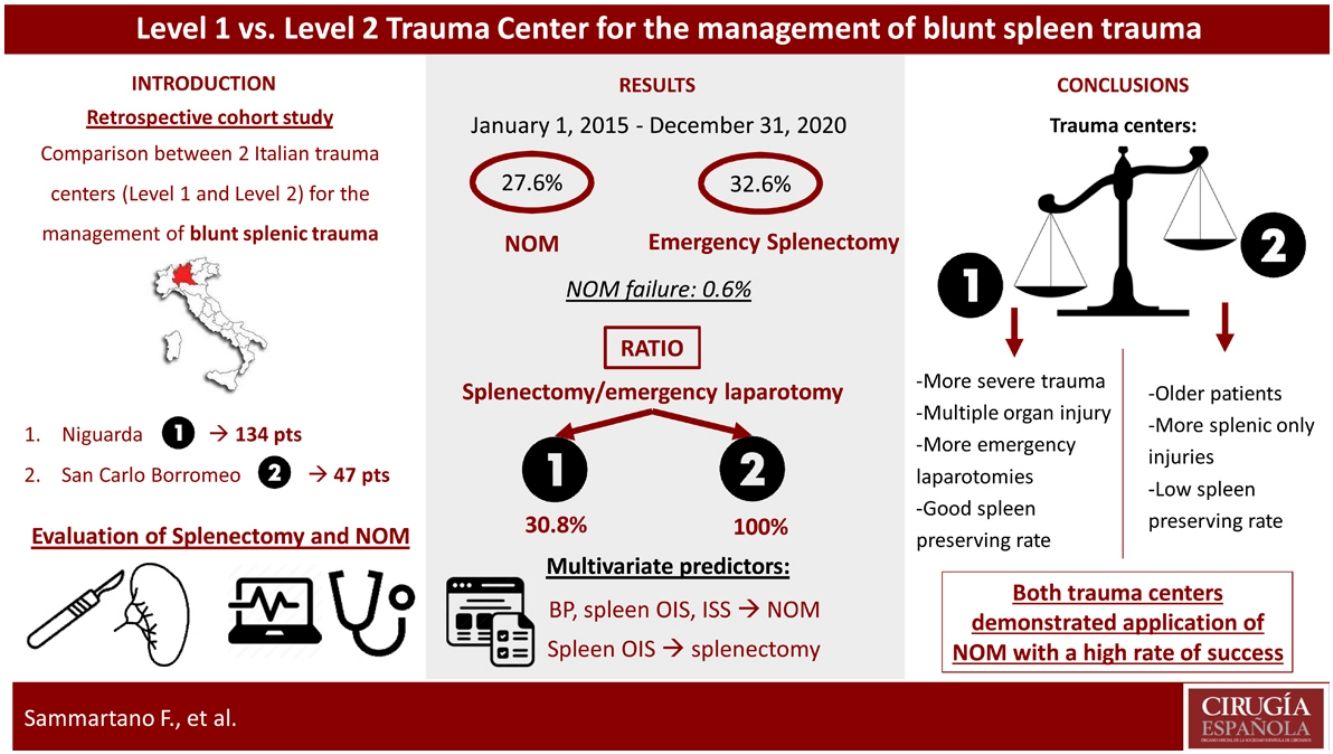

The management of blunt splenic trauma has evolved in the last years, from mainly operative approach to the non-operative management (NOM). The aim of this study is to investigate whether trauma center (TC) designation (level 1 and level 2) affects blunt splenic trauma management.

MethodsA retrospective analysis of blunt trauma patients with splenic injury admitted to 2 Italian TCs, Niguarda (level 1) and San Carlo Borromeo (level 2), was performed, receiving either NOM or emergency surgical treatment, from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2020. Univariate comparison was performed between the two centers, and multivariate analysis was carried out to find predictive factors associated with NOM and splenectomy.

Results181 patients were included in the study, 134 from level 1 and 47 from level 2 TCs. The splenectomy/emergency laparotomy ratio was inferior at level 1 TC for high-grade splenic injuries (30.8% for level 1 and 100% for level 2), whose patients presented higher incidence of other injuries. Splenic NOM failure was registered in only one case (3.3%). At multivariate analysis, systolic pressure, spleen organ injury scale (OIS) and injury severity score (ISS) resulted significant predictive factors for NOM, and only spleen OIS was predictive factor for splenectomy (Odds Ratio 0.14, 0.04–0.49 CI 95%, P < .01).

ConclusionBoth level 1 and 2 trauma centers demonstrated application of NOM with a high rate of success with some management difference in the treatment and outcome of patients with splenic injuries between the two types of TCs.

El manejo del traumatismo esplénico cerrado ha evolucionado en los últimos años, desde un abordaje mayoritariamente operatorio hasta el manejo no operatorio (NOM). El objetivo de este estudio es investigar si la designación de centro de trauma (CT) (nivel 1 y nivel 2) afecta el manejo del trauma esplénico contundente.

MétodosSe realizó un análisis retrospectivo de pacientes con trauma contuso con lesión esplénica ingresados en los TC Italianos de Niguarda (nivel 1) y San Carlo Borromeo (nivel 2), que recibieron tratamiento NOM o quirúrgico de emergencia, desde el 1 de enero de 2015 al 31 de diciembre de 2020. Se realizó una comparación univariante entre los dos centros, y se llevó a cabo un análisis multivariante para encontrar factores predictivos asociados con NOM y esplenectomía.

ResultadosSe incluyeron en el estudio 181 pacientes, 134 del nivel 1 y 47 del nivel 2 de CT. La relación esplenectomía/laparotomía de urgencia fue inferior en el TC de nivel 1 para las lesiones esplénicas de alto grado (30,8% para el nivel 1 y 100% para el nivel 2), cuyos pacientes presentaron mayor incidencia de otras lesiones. La falla NOM esplénica se registró solo en un caso (3,3%). En el análisis multivariado, la presión sistólica, la escala de lesión de órganos del bazo (OIS) y la puntuación de gravedad de la lesión (ISS) resultaron factores predictivos significativos para la NOM, y solo la OIS del bazo fue un factor predictivo para la esplenectomía (Odds Ratio 0.14, 0.04–0.49 IC 95%, P < ,01).

ConclusiónLos centros de trauma de nivel 1 y 2 demostraron la aplicación de NOM con una alta tasa de éxito con alguna diferencia de manejo en el tratamiento y el resultado de los pacientes con lesiones esplénicas entre los dos tipos de TC.

Spleen injury is very common in the case of blunt abdominal trauma1 and this organ is involved in about 30% of cases2. The management of splenic injury has evolved in the last years, from a mainly operative approach to the non-operative management (NOM) aiming at spleen preservation in selected patients3. NOM has become the treatment of choice for hemodynamically stable patients with no other indications for emergent surgery and this approach has reached a success rate of 95%4. The evolution of diagnostic and interventional technology together with the expertise of trauma teams has improved the application of NOM to a higher number of patients, allowing to conservatively manage also high-grade lesions3,4. Among the factors that may contribute to the success or failure of NOM, some are associated with the characteristics of the patients and the injuries themselves, others are linked to the aspects of the institution where trauma is managed1. There are significant differences among institutions around the world in terms of quality and performance and each country has its own rules to classify trauma centers5. Healthcare System in Italy is a regionally based health service, where each region organizes its emergency and trauma system. Emergency Departments (ED) and trauma centers (TC) are classified according to the Italian Ministry of Health criteria6. Pre-hospital triage and care are managed by the territorial emergency service7. The trauma system in Lombardy, a northern region of Italy, is organized into 4 levels of institutions: high-specialized trauma centers (level 1), trauma centers with neurosurgery (level 2), trauma centers without neurosurgery (level 3), and first-aid trauma centers (level 4). Level 1 TCs are the referral centers for the trauma of an area, with 24/7 coverage by all specialties. Level 2 and 3 TCs can provide 24/7 immediate care to trauma patients excluding some specialistic treatments only available in level 1 TCs. Level 4 TCs provide only emergency stabilization of trauma and transfer to a higher-level facility8. According to this classification, trauma hospitals network in Italy is quite different from the USA organization, and for the purpose of this article we considered only the Italian classification9. The influence of TC level on splenic injury management has never been explored in Italy.

In our study we compared two Italian institutions in Milan, the Lombardy capital, a level 1 TC, the Niguarda Hospital, and a level 2 TC, the San Carlo Borromeo Hospital, about the treatment of splenic blunt trauma patients, since these are the most important Milan metropolitan area TCs with the highest number of trauma patients admitted per year.

The study by Harbrecht et al.1 reported a retrospective analysis of data collected from the database of the Pennsylvania Trauma System Foundation, in the USA. To our knowledge our study is the first to compare different TC levels in Europe.

The primary aim of this study was to demonstrate whether NOM strategy of splenic injury may be followed at both level 1 and 2 TCs with a high rate of success. The second aim was to point out the differences and the predictive factors in the management of blunt splenic traumas between the two institutions.

MethodsWe performed a retrospective analysis of blunt trauma patients with splenic injury (ICD-9-CM codes 865.xx) admitted to the ED of Niguarda (L1) and San Carlo Borromeo (L2) hospitals in Milan, Italy from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2020.

All patients received either NOM with or without angioembolization (AE) or emergency surgical treatment. Failure of NOM was defined when splenectomy was performed after an initial NOM attempt, until 48 h from admission.

Demographic and clinical data, vital signs (systolic pressure and pulse rate), procedures performed, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), pre-injury American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification (ASA), Injury Severity Score (ISS), Death Probability (Trauma and Injury Severity Scoring – TRISS), Organ Injury Scale (OIS) assigned to the splenic injury, presence of other injuries, development of complications, mortality, and length of hospital stay (LOS) were prospectively collected in each TC database, exported and retrospectively analyzed. Vitals were registered at ED access. ISS was defined using the ICD-9-CM Injury Severity Score (ICISS)10. The Trauma and Injury Severity Scoring (Death Probability TRISS) system was based on a combination of patient age, Trauma Score (TS), and ISS11. The splenic injury was defined according to the computed tomography (CT-scan) diagnosis or intraoperatively. The diagnosis was confirmed by a radiologist or staff trauma surgeon and graded according to the OIS of the American Association for Surgery of Trauma (AAST)12. In both centers angiography is available 24 h every day. The trauma teams are led by general surgeons skilled in the management of polytrauma patients, L1 has a dedicated trauma team staff while L2 has an hybrid trauma service within the two surgical departments of the hospital. The other difference between the two TCs is the absence of cardiac, plastic and maxillo-facial surgery in L2. Moreover in L1 interventional radiologists are available on site 24 h every day, whereas in L2 they are available on site during the day and on call during the night.

All patients underwent initial assessment and management, according to ATLS guidelines13. Hemodynamically unstable patients with evidence of hemoperitoneum at focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) underwent emergency surgery. Hemodynamically stable or stabilized patients were planned for contrast-enhanced CT-scan. Therapeutic total or partial, when possible, AE was performed for any OIS ≥ 4 (contrast extravasations or pseudoaneurysm) in hemodynamically stable patients. Other indications included evidence of vascular injury on CT scan and/or evidence of ongoing bleeding.

Patients undergoing NOM were closely followed with regular monitoring of vitals, hemoglobin values and clinical examinations until discharge and CT-scan at 48−72 h, with short-course antibiotic prophylaxis no longer than 48 h and vaccine administration at discharge (Pneumococcal, Haemophilus influenza and Meningococcal). We performed a first comparison between the two trauma centers and then 2 separate analysis for patients who underwent NOM and splenectomy. Splenic OIS was analyzed separately according to NOM, emergency laparotomy, splenectomy, other abdominal and non-abdominal injuries, TRISS, and ISS in the two centers. Multivariate analysis was carried out to find independent predictive factors associated with NOM and splenectomy.

The procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local and national ethical committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Since the procedures were carried out with human subjects receiving emergency treatment, no legally informed consent could be obtained, thus a waiver of regulatory requirements for obtaining and documenting informed consent was applied.

Statistical analysisUnivariate comparison among categorical data was performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were presented as medians and compared using Mann-Whitney U test. To assess the association between a trauma center and NOM or splenectomy (separate models) we used generalized estimating equations for multivariate logistic regression models to calculate the risk-adjusted odds ratio that a patient had NOM or splenectomy, controlling for important confounders. These variables included age, systolic pressure, pulse rate, spleen injury score, death probability, and ISS. The influence of trauma centers was also evaluated with this analysis. A value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS software (IBM SPSS 23, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

ResultsA total of 181 patients were included in the study, 134 (74%) from L1 and 47 (26%) from L2. Forty-eight (26.5%) patients were females and 133 (73.5%) males. The median age was 43 years (range 2–97), 12 patients were in chronic therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and 7 with oral anticoagulant (OAC). Pre-injury ASA classification was distributed as follow: 118 (65.2%) patients ASA 1, 49 (27.1%) ASA 2 and 14 (7.7%) ASA 3. The median value of systolic pressure, pulse rate, and GCS were 120 mmHg (range 0–204), 90 bpm (range 0–180), and 15 (range 3–15), respectively. In 50 (27.6%) cases NOM was performed, whereas 59 (32.6%) patients underwent emergency splenectomy. Angiography was used in 49 (27.1%) cases. Spleen OIS was distributed as follows: 45 (24.9%) grade 1, 32 (17.7%) grade 2, 36 (19.9%) grade 3, 43 (23.8%) grade 4, 25 (13.8%) grade 5. In 89 (49.2%) cases concomitant abdominal injuries were associated and 153 (84.5%) patients presented also extra-abdominal injury. The median TRISS was 6.2 (range 0–99.9) and the median ISS was 29 (range 4–75). Second look surgery was performed in 23 (12.7%) patients whereas NOM failure (delayed splenectomy) was registered in only 1 case (0.6%) at L1, 4 days after admission/NOM. The median LOS was 14 days (range 0–125) and overall mortality was 10.5% (19 patients).

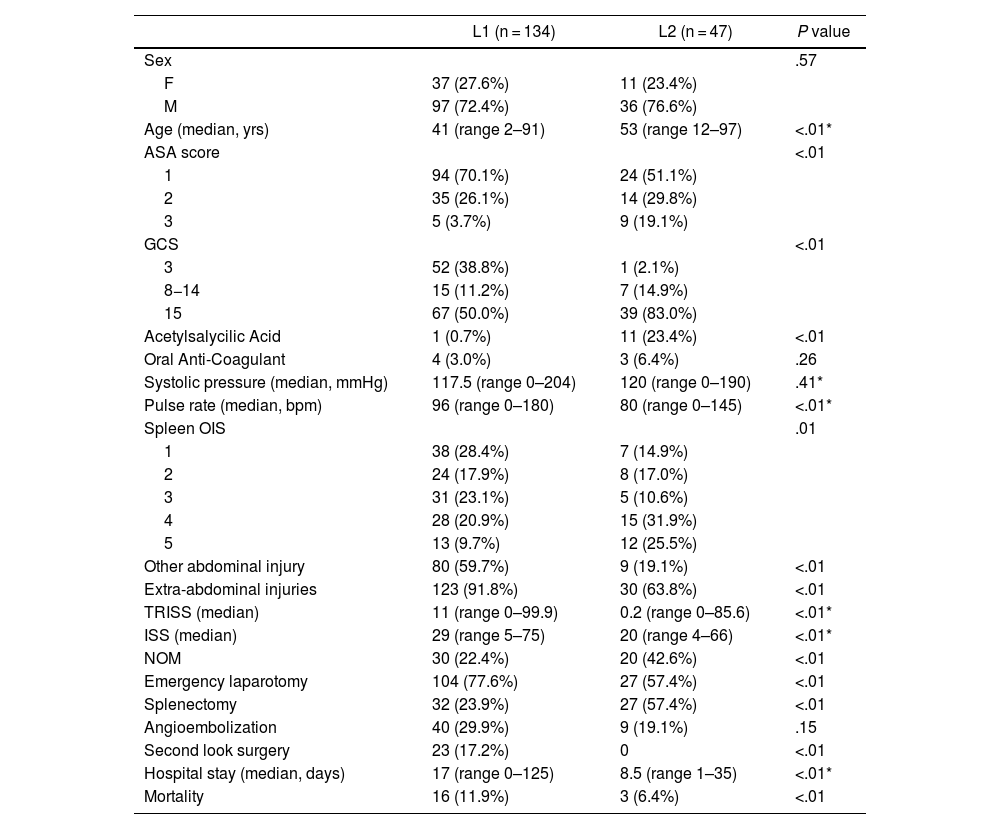

A complete comparison between the groups of patients from L1 and L2 trauma centers is available in Table 1. The two groups were comparable for sex, use of OAC, systolic pressure, and use of angiography. In L1 population age resulted lower, there was a lower incidence of pre-injury ASA type 3 patients (3.7% vs. 19.1% at L2, P < .01) and higher incidence of GCS 3 patients (38.8% vs. 2.1%, P < .01). At L2 a higher incidence of high-grade spleen injuries (spleen OIS 4 and 5) was recorded, whereas L1 patients presented significantly more abdominal and extra-abdominal injuries. This aspect was confirmed by significantly higher TRISS and ISS (11 and 29 vs. 0.2 and 20 at L2 vs. L1, P < .01). NOM was performed more frequently at L2, compared with emergency laparotomy registered in more cases at L1. Among emergency laparotomies, splenectomy was performed in more cases at L2 (Table 1). The splenectomy/emergency laparotomy ratio was 30.8% for L1 and 100% for L2, respectively. Hospital stay and mortality were higher at L1 (17 vs. 8.5 days, P < .01 and 11.9% vs. 6.4%, P < .01).

Comparison between the groups of patients from Niguarda (L1) and San Carlo Borromeo (L2) trauma centers.

| L1 (n = 134) | L2 (n = 47) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | .57 | ||

| F | 37 (27.6%) | 11 (23.4%) | |

| M | 97 (72.4%) | 36 (76.6%) | |

| Age (median, yrs) | 41 (range 2–91) | 53 (range 12–97) | <.01* |

| ASA score | <.01 | ||

| 1 | 94 (70.1%) | 24 (51.1%) | |

| 2 | 35 (26.1%) | 14 (29.8%) | |

| 3 | 5 (3.7%) | 9 (19.1%) | |

| GCS | <.01 | ||

| 3 | 52 (38.8%) | 1 (2.1%) | |

| 8−14 | 15 (11.2%) | 7 (14.9%) | |

| 15 | 67 (50.0%) | 39 (83.0%) | |

| Acetylsalycilic Acid | 1 (0.7%) | 11 (23.4%) | <.01 |

| Oral Anti-Coagulant | 4 (3.0%) | 3 (6.4%) | .26 |

| Systolic pressure (median, mmHg) | 117.5 (range 0–204) | 120 (range 0–190) | .41* |

| Pulse rate (median, bpm) | 96 (range 0–180) | 80 (range 0–145) | <.01* |

| Spleen OIS | .01 | ||

| 1 | 38 (28.4%) | 7 (14.9%) | |

| 2 | 24 (17.9%) | 8 (17.0%) | |

| 3 | 31 (23.1%) | 5 (10.6%) | |

| 4 | 28 (20.9%) | 15 (31.9%) | |

| 5 | 13 (9.7%) | 12 (25.5%) | |

| Other abdominal injury | 80 (59.7%) | 9 (19.1%) | <.01 |

| Extra-abdominal injuries | 123 (91.8%) | 30 (63.8%) | <.01 |

| TRISS (median) | 11 (range 0–99.9) | 0.2 (range 0–85.6) | <.01* |

| ISS (median) | 29 (range 5–75) | 20 (range 4–66) | <.01* |

| NOM | 30 (22.4%) | 20 (42.6%) | <.01 |

| Emergency laparotomy | 104 (77.6%) | 27 (57.4%) | <.01 |

| Splenectomy | 32 (23.9%) | 27 (57.4%) | <.01 |

| Angioembolization | 40 (29.9%) | 9 (19.1%) | .15 |

| Second look surgery | 23 (17.2%) | 0 | <.01 |

| Hospital stay (median, days) | 17 (range 0–125) | 8.5 (range 1–35) | <.01* |

| Mortality | 16 (11.9%) | 3 (6.4%) | <.01 |

L1: Niguarda; L2: San Carlo Borromeo; ASA: pre-injury American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; OIS: Organ Injury Scale; TRISS: Trauma and Injury Severity Scoring; ISS: Injury Severity Score; NOM: non-operative management.

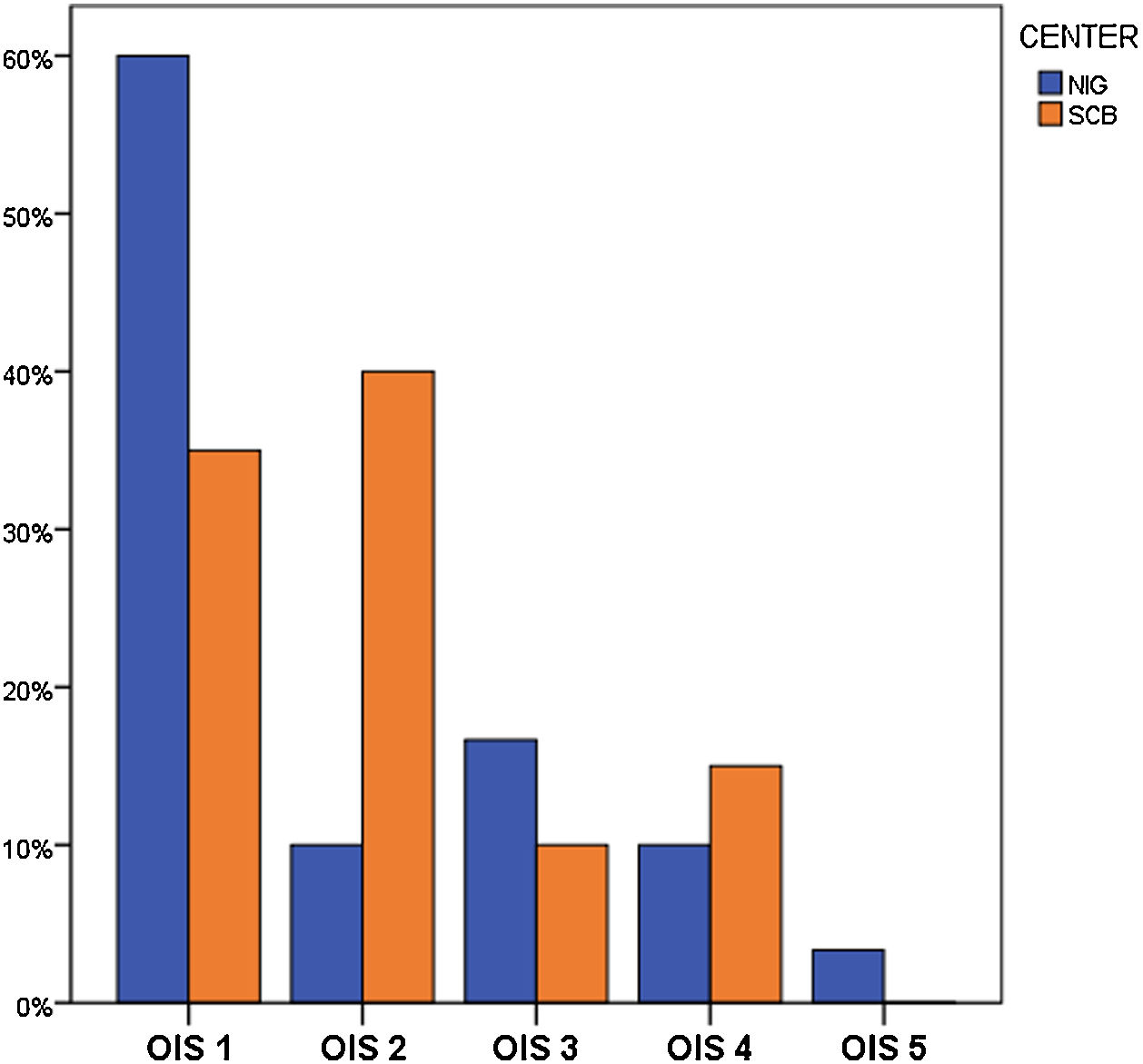

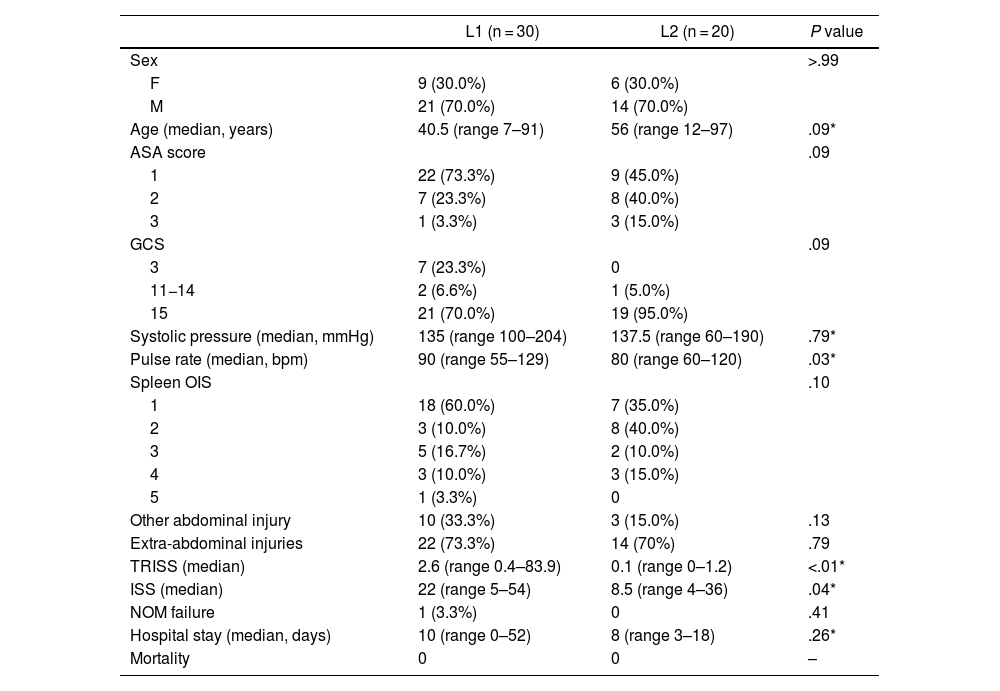

In the group of patients treated with NOM (Table 2, Fig. 1) there was no statistically significant difference about sex, age, ASA score, GCS, systolic pressure, spleen OIS, presence of other abdominal or non-abdominal injuries, elective surgical procedures, hospital stay, and mortality. Pulse rate resulted significantly lower at L2 (80 vs. 90 bpm, P = .03), whereas TRISS and ISS resulted higher at L1 (2.6 vs. 0.1, P < .01 and 22 vs. 8.5, P = .04).

Comparison between the groups of patients from Niguarda (L1) and San Carlo Borromeo (L2) trauma centers according to Non-Operative Management.

| L1 (n = 30) | L2 (n = 20) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | >.99 | ||

| F | 9 (30.0%) | 6 (30.0%) | |

| M | 21 (70.0%) | 14 (70.0%) | |

| Age (median, years) | 40.5 (range 7–91) | 56 (range 12–97) | .09* |

| ASA score | .09 | ||

| 1 | 22 (73.3%) | 9 (45.0%) | |

| 2 | 7 (23.3%) | 8 (40.0%) | |

| 3 | 1 (3.3%) | 3 (15.0%) | |

| GCS | .09 | ||

| 3 | 7 (23.3%) | 0 | |

| 11−14 | 2 (6.6%) | 1 (5.0%) | |

| 15 | 21 (70.0%) | 19 (95.0%) | |

| Systolic pressure (median, mmHg) | 135 (range 100–204) | 137.5 (range 60–190) | .79* |

| Pulse rate (median, bpm) | 90 (range 55–129) | 80 (range 60–120) | .03* |

| Spleen OIS | .10 | ||

| 1 | 18 (60.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | |

| 2 | 3 (10.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | |

| 3 | 5 (16.7%) | 2 (10.0%) | |

| 4 | 3 (10.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | |

| 5 | 1 (3.3%) | 0 | |

| Other abdominal injury | 10 (33.3%) | 3 (15.0%) | .13 |

| Extra-abdominal injuries | 22 (73.3%) | 14 (70%) | .79 |

| TRISS (median) | 2.6 (range 0.4–83.9) | 0.1 (range 0–1.2) | <.01* |

| ISS (median) | 22 (range 5–54) | 8.5 (range 4–36) | .04* |

| NOM failure | 1 (3.3%) | 0 | .41 |

| Hospital stay (median, days) | 10 (range 0–52) | 8 (range 3–18) | .26* |

| Mortality | 0 | 0 | – |

L1: Niguarda; L2: San Carlo Borromeo; ASA: pre-injury American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; OIS: Organ Injury Scale; TRISS: Trauma and Injury Severity Scoring; ISS: Injury Severity Score; NOM: non-operative management.

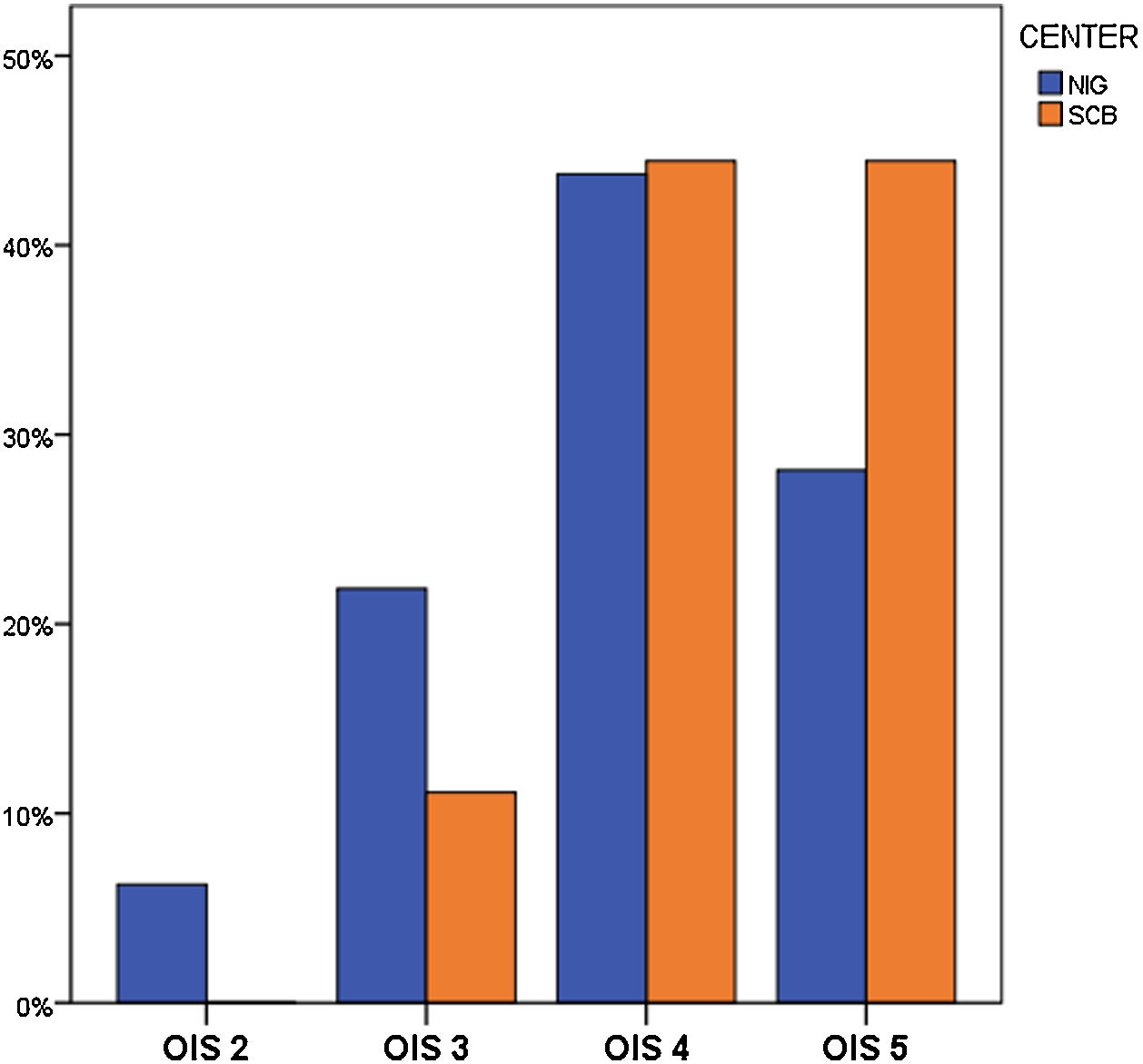

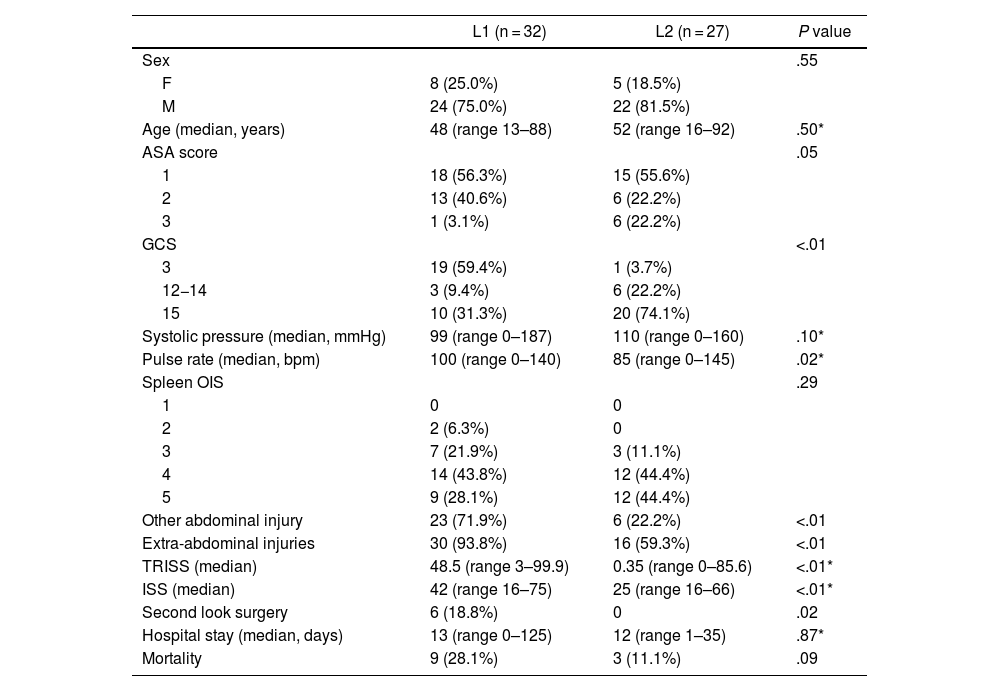

Patients treated with emergency splenectomy (Table 3, Fig. 2) were comparable according to sex, age, systolic pressure, spleen OIS, hospital stay, and mortality. L1’s patients presented higher incidence of other abdominal and extra-abdominal injuries (71.9% vs. 22.2%, P < .01 and 93.8% vs. 59.3%, P < .01, respectively) and consequently higher TRISS and ISS (48.5 vs. 0.35, P < .01 and 42 vs. 25, P < .01, respectively). NOM failure was registered in only one case at L1 hospital (3.3%).

Comparison between the groups of patients from Niguarda (L1) and San Carlo Borromeo (L2) trauma centers according to splenectomy.

| L1 (n = 32) | L2 (n = 27) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | .55 | ||

| F | 8 (25.0%) | 5 (18.5%) | |

| M | 24 (75.0%) | 22 (81.5%) | |

| Age (median, years) | 48 (range 13–88) | 52 (range 16–92) | .50* |

| ASA score | .05 | ||

| 1 | 18 (56.3%) | 15 (55.6%) | |

| 2 | 13 (40.6%) | 6 (22.2%) | |

| 3 | 1 (3.1%) | 6 (22.2%) | |

| GCS | <.01 | ||

| 3 | 19 (59.4%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| 12−14 | 3 (9.4%) | 6 (22.2%) | |

| 15 | 10 (31.3%) | 20 (74.1%) | |

| Systolic pressure (median, mmHg) | 99 (range 0–187) | 110 (range 0–160) | .10* |

| Pulse rate (median, bpm) | 100 (range 0–140) | 85 (range 0–145) | .02* |

| Spleen OIS | .29 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 2 (6.3%) | 0 | |

| 3 | 7 (21.9%) | 3 (11.1%) | |

| 4 | 14 (43.8%) | 12 (44.4%) | |

| 5 | 9 (28.1%) | 12 (44.4%) | |

| Other abdominal injury | 23 (71.9%) | 6 (22.2%) | <.01 |

| Extra-abdominal injuries | 30 (93.8%) | 16 (59.3%) | <.01 |

| TRISS (median) | 48.5 (range 3–99.9) | 0.35 (range 0–85.6) | <.01* |

| ISS (median) | 42 (range 16–75) | 25 (range 16–66) | <.01* |

| Second look surgery | 6 (18.8%) | 0 | .02 |

| Hospital stay (median, days) | 13 (range 0–125) | 12 (range 1–35) | .87* |

| Mortality | 9 (28.1%) | 3 (11.1%) | .09 |

L1: Niguarda; L2: San Carlo Borromeo; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; OIS: Organ Injury Scale; TRISS: Trauma and Injury Severity Scoring; ISS: Injury Severity Score; NOM: non-operative management.

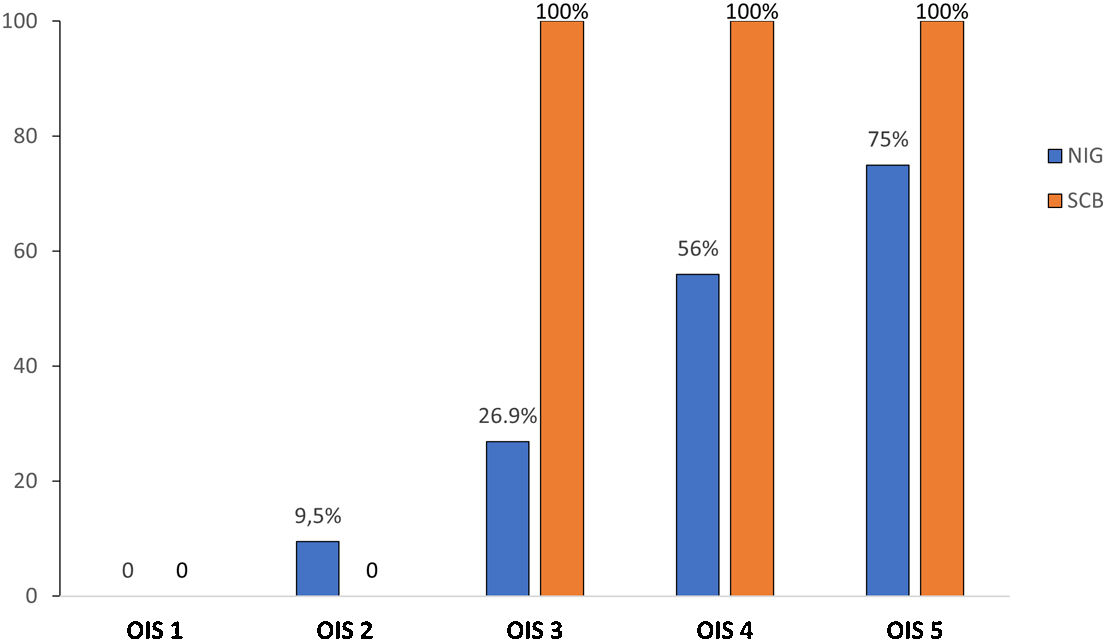

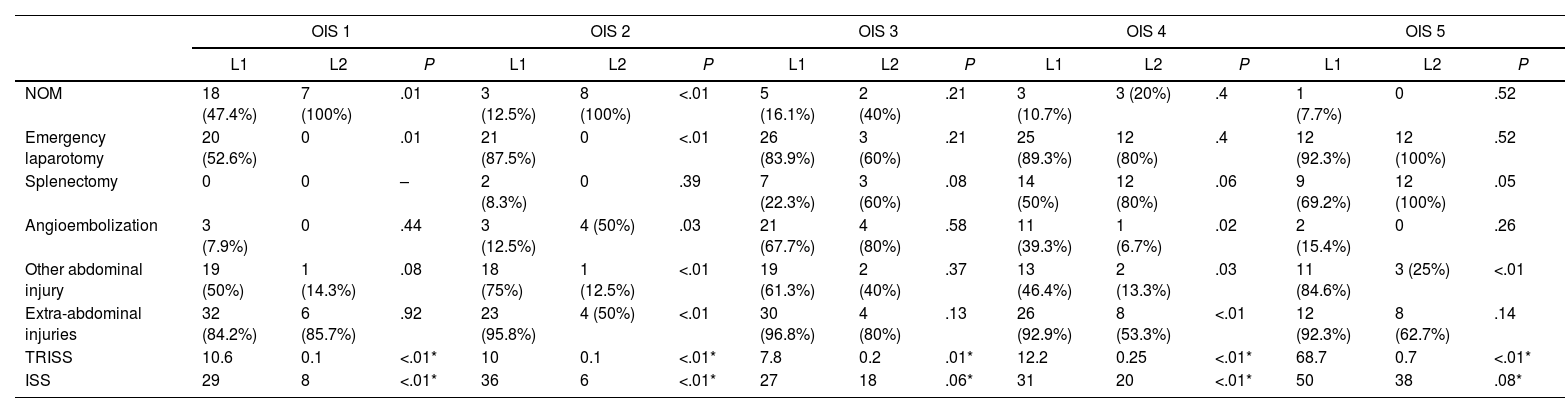

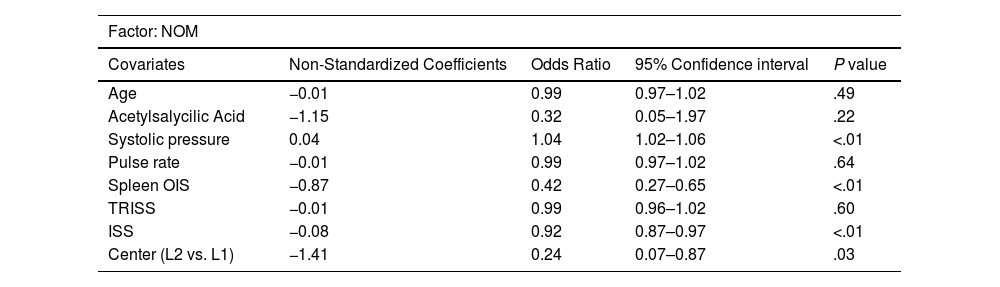

In the spleen OIS analysis, no significant difference in the splenectomy rate was registered for all the OIS grades, emergency laparotomy was performed more frequently at L1, related to the presence of other abdominal and non-abdominal injuries with higher TRISS and ISS even in case of low-grade splenic injuries (Table 4). The splenectomy/emergency laparotomy rate was comparable in the two centers for low-grade splenic injuries (OIS 1-2) and it was inferior at L1 for high-grade splenic injuries (OIS 3-4-5) (Fig. 3). At multivariate logistic regression, systolic pressure, spleen OIS and ISS resulted significant predictive factors for NOM (Table 5). There was also a statistically significant difference between the two centers, resulting an Odds Ratio of 0.24 (0.07–0.87 CI 95%, P = .03) in the comparison L1 vs. L2. However only spleen OIS resulted significant predictive factor for splenectomy, with a statistically significant difference between L1 vs. L2 (Odds Ratio 0.14, 0.04–0.49 CI 95%, P < .01) (Table 5).

Correlation between splenic organ injury scale (OIS) and trauma centers.

| OIS 1 | OIS 2 | OIS 3 | OIS 4 | OIS 5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | P | L1 | L2 | P | L1 | L2 | P | L1 | L2 | P | L1 | L2 | P | |

| NOM | 18 (47.4%) | 7 (100%) | .01 | 3 (12.5%) | 8 (100%) | <.01 | 5 (16.1%) | 2 (40%) | .21 | 3 (10.7%) | 3 (20%) | .4 | 1 (7.7%) | 0 | .52 |

| Emergency laparotomy | 20 (52.6%) | 0 | .01 | 21 (87.5%) | 0 | <.01 | 26 (83.9%) | 3 (60%) | .21 | 25 (89.3%) | 12 (80%) | .4 | 12 (92.3%) | 12 (100%) | .52 |

| Splenectomy | 0 | 0 | – | 2 (8.3%) | 0 | .39 | 7 (22.3%) | 3 (60%) | .08 | 14 (50%) | 12 (80%) | .06 | 9 (69.2%) | 12 (100%) | .05 |

| Angioembolization | 3 (7.9%) | 0 | .44 | 3 (12.5%) | 4 (50%) | .03 | 21 (67.7%) | 4 (80%) | .58 | 11 (39.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | .02 | 2 (15.4%) | 0 | .26 |

| Other abdominal injury | 19 (50%) | 1 (14.3%) | .08 | 18 (75%) | 1 (12.5%) | <.01 | 19 (61.3%) | 2 (40%) | .37 | 13 (46.4%) | 2 (13.3%) | .03 | 11 (84.6%) | 3 (25%) | <.01 |

| Extra-abdominal injuries | 32 (84.2%) | 6 (85.7%) | .92 | 23 (95.8%) | 4 (50%) | <.01 | 30 (96.8%) | 4 (80%) | .13 | 26 (92.9%) | 8 (53.3%) | <.01 | 12 (92.3%) | 8 (62.7%) | .14 |

| TRISS | 10.6 | 0.1 | <.01* | 10 | 0.1 | <.01* | 7.8 | 0.2 | .01* | 12.2 | 0.25 | <.01* | 68.7 | 0.7 | <.01* |

| ISS | 29 | 8 | <.01* | 36 | 6 | <.01* | 27 | 18 | .06* | 31 | 20 | <.01* | 50 | 38 | .08* |

L1: Niguarda; L2: San Carlo Borromeo; OIS: Organ Injury Scale; TRISS: Trauma and Injury Severity Scoring; ISS: Injury Severity Score; NOM: non-operative management.

Multivariate logistic regression.

| Factor: NOM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Non-Standardized Coefficients | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | .49 |

| Acetylsalycilic Acid | −1.15 | 0.32 | 0.05–1.97 | .22 |

| Systolic pressure | 0.04 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.06 | <.01 |

| Pulse rate | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | .64 |

| Spleen OIS | −0.87 | 0.42 | 0.27–0.65 | <.01 |

| TRISS | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 | .60 |

| ISS | −0.08 | 0.92 | 0.87–0.97 | <.01 |

| Center (L2 vs. L1) | −1.41 | 0.24 | 0.07–0.87 | .03 |

| Factor: splenectomy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.15 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | .23 |

| Acetylsalycilic Acid | 0.27 | 1.31 | 0.18–9.26 | .79 |

| Systolic pressure | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | .09 |

| Pulse rate | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | .43 |

| Spleen OIS | 1.47 | 4.34 | 2.61–7.21 | <.01 |

| TRISS | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.04 | .39 |

| ISS | 0.02 | 1.03 | 0.98–1.08 | .32 |

| Center (L2 vs. L1) | −1.95 | 0.14 | 0.04–0.49 | <.01 |

L1: Niguarda; L2: San Carlo Borromeo; OIS: Organ Injury Scale; TRISS: Trauma and Injury Severity Scoring; ISS: Injury Severity Score; NOM: non-operative management.

This study retrospectively analyzed all patients with blunt splenic injuries admitted to the two major trauma centers in Milan in the last 6 years. L1 trauma center is the referral center for major trauma in Milan metropolitan area (level 1) and L2 is a level 2 trauma center, according to the Italian Ministry of Health criteria6. In both hospitals, trauma services are organized with general surgeons, anesthesiologists, orthopedic surgeons, and radiologists available 24 h every day. Due to the different trauma-related workload, L1 has a dedicated trauma team staff dealing with trauma and acute care surgery, L2 has a trauma service within the two surgical departments dealing with trauma, acute care, and elective surgery. At L2 neurosurgeons and interventional radiologists work on a 12-h daily rotation, and on-call during the non-working hours, with operating and angiography rooms available 24/7, whereas at L1 neurosurgeons work on 24/7 rotation. According to the classification of trauma centers in Italy8, L1 hospital provides more specialistic care with the availability of different specialties.

In this study, we compared patients admitted for blunt splenic injury to the EDs of the two trauma centers treated either by NOM with or without AE or emergency surgery. In 27.6% NOM was performed whereas emergency splenectomy was carried out in 32.6% of cases.

As regards splenic injury, there was a higher incidence of lower-grade injuries (OIS 1-2) at L1 and greater incidence of high-grade injuries at L2 (OIS 4-5), which presented also a statistically significant older population (53 vs. 41 years, P < .01 for L2 and L1, respectively).

Between the two centers, there was a statistically significant difference with regards to NOM, emergency laparotomy, and splenectomy rates. NOM was performed more frequently at L2, compared with emergency laparotomy registered in more cases at L1. Among emergency laparotomies, splenectomy was performed in more cases at L2 (Table 1), with splenectomy/emergency laparotomy ratio of 30.8% and 100% at L1 and L2, respectively. So, the likelihood of performing a spleen preserving surgery was superior at level 1 trauma center of about 70% compared to the level 2 trauma center. This result may appear conflicting with the more frequent use of NOM at L2, however, it is related to the different populations of the two centers. In fact, L1’s population was mainly composed of more complex cases with a greater incidence of abdominal and extra-abdominal injuries other than the splenic injury alone (Table 1). This data is confirmed by the statistically different TRISS and ISS registered in the two centers (11 vs. 0.2 and 29 vs. 20, P < .01). Moreover, L2’s population was older than L1’s and this may also justify the higher incidence of splenectomy at the level 2 trauma center, though this factor was not found to be significant at multivariate analysis (Table 5). As a referral center for major trauma, L1 is specialized in the treatment of complex trauma patients in whom NOM is not always viable, due to the multiple organ lesions that may need emergent surgical treatment, especially in patients with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) or hemodynamically unstable patients. The latter aspect may be explained by the statistically different pulse rate between the two populations (96 vs. 80 bpm, P < .01 at L1 and L2, respectively), which may justify the higher incidence of emergency laparotomies at L1.

It has been frequently reported in the literature that spleen preserving treatment is safe for low-grade injures14–16, whereas emergency splenectomy is often necessary for high-grade injuries.

In centers with interventional radiology availability, even higher-grade spleen injuries can undergo salvage rather than laparotomy removal17 and in our study, some high-grade injuries (OIS 4-5) were successfully treated with NOM (Fig. 1, Table 4), especially at level 1 trauma center. The use of AE was similar in the two centers (29.9% vs. 19.1%, P = .15) confirming the good level of skilled management, but a greater incidence of AE was registered at L1 for OIS 4-5 injuries (Table 4). In the analysis of spleen OIS (Table 4), no significant differences were registered in the splenectomy rates in the two centers for each OIS grade, however, this procedure was slightly more frequently performed at L2, in particular for high-grade splenic injuries (OIS 4-5). This result is also related to the emergency laparotomy rate, more frequently performed at L1, as discussed above. The splenectomy/emergency laparotomy ratio was similar in the two centers for low-grade splenic injuries (OIS 1-2), whereas it was lower at L1 for high-grade splenic injuries (OIS 3-4-5) revealing a possible better attitude for the level 1 trauma center of conservatively manage also high-grade splenic injuries, regardless of other abdominal or extra-abdominal injuries. Moreover, the ratio difference between the 2 centers was inversely related to the splenic OIS, decreasing from OIS 3 to OIS 5 injuries (Fig. 3). The specialization of level 1 trauma center in the management of complex trauma patients can also be demonstrated with the more frequent use of AE in high-grade splenic injuries and that in some cases was associated with the surgical treatment (Table 4).

Some studies have reported the results about AE for patients approached with NOM. A metanalysis reported no difference in NOM failure rates, mortality, hospital length of stay, or blood transfusion requirements between patients treated with AE and those treated with NOM alone18. These findings were similar to those of a previous meta-analysis which reported a NOM failure rate of 15.7% with AE a 17.8% with observation alone19. In our study NOM failure has been registered in only one case in all the population, with a rate of 2% among patients approached with NOM (3.3% for L1 only).

Another finding of our study was the significant difference in-hospital stay and mortality between the two centers. This may be linked to the different populations, with major trauma patients admitted and treated at L1.

In the analysis of NOM cases, no significant differences were registered between the two centers, except for TRISS and ISS. These findings are important from different points of view: first, both centers were able to apply NOM with similar good results; second, L1 could use NOM even for more complex cases, without increasing the hospital stay, with an acceptable NOM failure rate and with no mortality.

Operative management of splenic injuries can be performed in non-responder hemodynamically unstable patients or in severe TBI injuries to prevent secondary brain damage. This condition is frequently observed in high-ISS trauma, high-grade injuries, and patients with associated abdominal or extra-abdominal injuries20–22. In the analysis of splenectomy cases, no differences in terms of hospital stay and mortality were registered between the two centers (Table 3). Even in this group, L1’s cases were more complex, but this factor did not affect the splenectomy rate and the management of high-grade splenic injuries, which were similar in the two centers (Fig. 2). These results confirm how facilities for immediate resuscitation, angiography, and ICU availability together with the confidence of the trauma team are well established in the two institutions.

In the multivariate analysis spleen OIS resulted a significant predictor of both NOM and splenectomy, whereas systolic pressure and ISS were predictors of NOM only. This result confirms the important role of the diagnostic phase to perform correct management. Some guidelines and consensus conferences3,4 stated that hemodynamically unstable patients should undergo laparotomy, thus leaving severity-of-injury metrics as the most discriminating predictors for the management of these cases. In fact, the success of NOM is mainly based on an accurate patient selection with correct grading of splenic injuries, and the identification of the associated intra-abdominal injuries which may preclude NOM. This is only possible with an accurate diagnostic phase by contrast-enhanced CT-scan that is considered the modality of choice to diagnose and characterize splenic injury4. CT scan also allows the identification of possible contrast extravasation which may help to select cases for AE, another factor that can increase the success rate of NOM. All these features should be possible only in an institution with the capabilities for monitoring, serial clinical evaluation, and 24/7 operating room availability23,24.

Another significant predictor at multivariate analysis was the center where NOM or splenectomy were performed. L2 resulted directly associated with the risk of NOM and splenectomy. This may appear as a conflicting result, however, it is linked to the results of univariate analysis, where both NOM and splenectomy resulted more frequently performed at L2.

The level 2 trauma center had similar outcomes like the level 1 hospital, suggesting that NOM is as safe as surgical operation for spleen injury. Therefore, regardless of the institution level, if the resources are sufficient, NOM should be considered safe also in the level 2 center and it can be applied as a first-line treatment choice in hemodynamically stable patients.

This study has some limitations. First, the population is not homogeneous, with a prevalence of high-grade injuries at L1 which may affect the results of the study. In particular, for patients with multiple abdominal injuries, identifying the principal abdominal injury driving clinical decision-making may not be easily decipherable. Second, NOM requires diagnosis with an injury scale defined by diagnostic imaging. Variability in organ injury grading may occur and confound this analysis. Moreover, patients with multiple abdominal or extra-abdominal injuries were treated based on clinical and radiological findings and spleen injury was not always the most important lesion to drive clinical management. Third, the population was not only composed of adult patients, but also some pediatric cases were included, and we know that pediatric splenic blunt trauma management may be different from adults3,25. Finally, this is a retrospective study where the accuracy of the results is also dependent on the accuracy of data, retrieved retrospectively.

ConclusionThis study demonstrates that some management difference exists in the treatment and outcome of patients with splenic injuries between the two Milan trauma centers of different level.

Both level 1 and 2 trauma centers demonstrated application of NOM with a high rate of success, but with more confidence in the level 1 trauma center for high-grade injuries.

Level 1 trauma center treated more frequently severe trauma with multiple organ injuries and hemodynamically unstable patients who underwent more frequently emergency laparotomy with a good spleen preserving rate and NOM approach when feasible. Also, pediatric traumas were more frequently centralized and treated at level 1 trauma center.

Level 2 trauma center treated less severe trauma with predominantly splenic injury and older patients who were adequately approached with NOM, especially for low-grade injuries, but spleen-preserving surgery was rarely applied in the case of emergency laparotomy for high-grade injuries.

Our results also show the efficiency of the pre-hospital triage and care managed by the territorial emergency service of Lombardy region.

Competing interests and fundingNone.

Authors’ contributionsFabrizio Sammartano contributed in the study design, data collection and data interpretation. Francesco Ferrara contributed in the study design, data interpretation, literature search, and writing. Laura Benuzzi, Caterina Baldi and Valeria Conalbi contributed in the data collection and literature search. Roberto Bini, Stefania Cimbanassi, Osvaldo Chiara and Marco Stella contributed in study design and critical revision.

None.