The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Corona Virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak that was initially detected in China was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020. The international underestimation of the problem, together with the high transmissibility of the virus and the lack of resources, caused an unprecedented situation worldwide. This led to the saturation of national healthcare systems, and Spain was one of the most affected countries. Some of the most common manifestations of the disease produced by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, known as COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019), include fever, dry cough, dyspnea, myalgias, fatigue, lymphopenia, elevated acute phase reactant levels and evidence of pneumonia on imaging studies.1

Due to the saturation of the healthcare system, hospitals and medical professionals have had to reorganize and adapt to be able to provide care for the high number of infected patients.2 With regard to urgent surgical pathology, there was a notable decrease in patients, while patients presented with more advanced disease.3

It is interesting to understand how the coexistence of SARS-CoV-2 infection can affect any type of acute abdominal pathology. Since many patients with COVID-19 disease present digestive symptoms,4 these can mask underlying surgical pathology. We present the case of a patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection and complicated acute appendicitis.

The patient is a 52-year-old woman with a history of dyslipidemia and hypertension, who came to the emergency room due to epigastric pain associated with fever, severe asthenia, ageusia, anosmia and loss of appetite over the past 7 days. Upon physical examination, she presented generalized abdominal pain, mainly in the right hemiabdomen, with no signs of generalized peritoneal irritation.

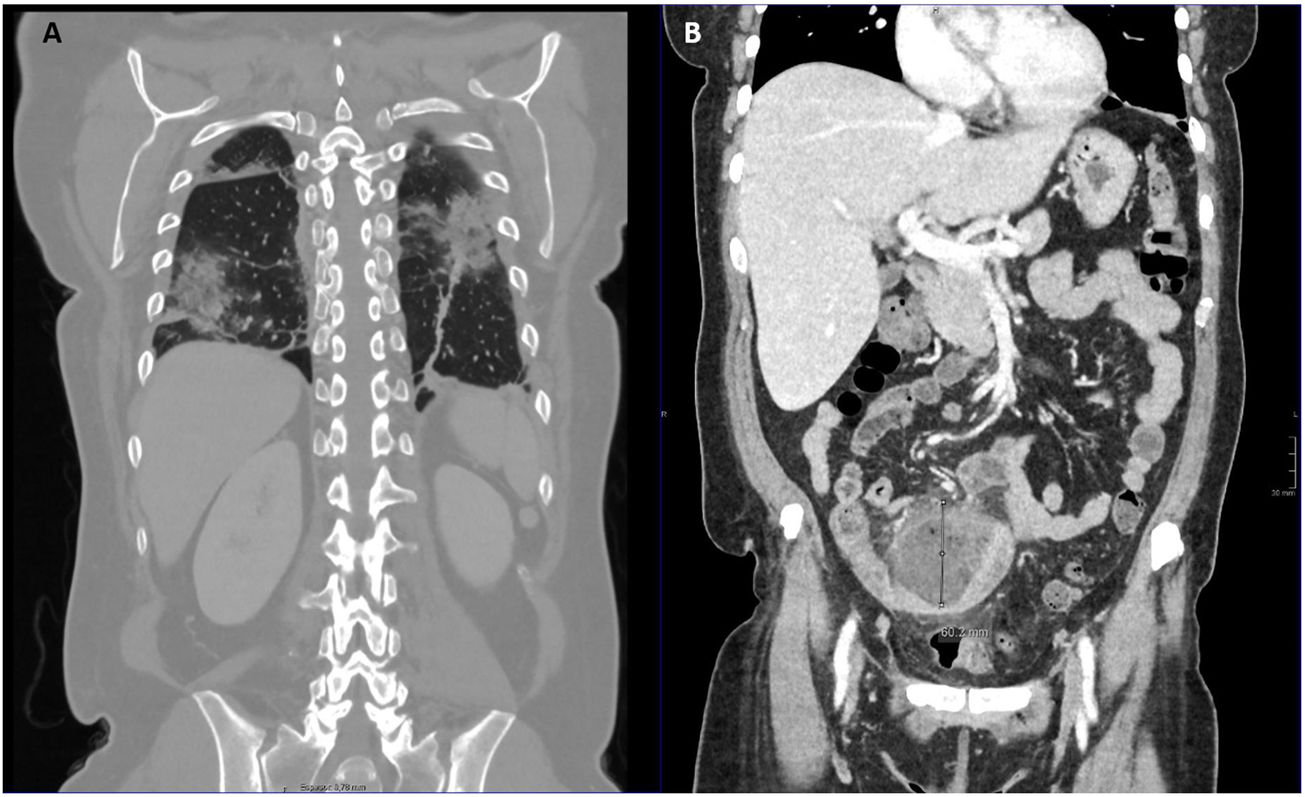

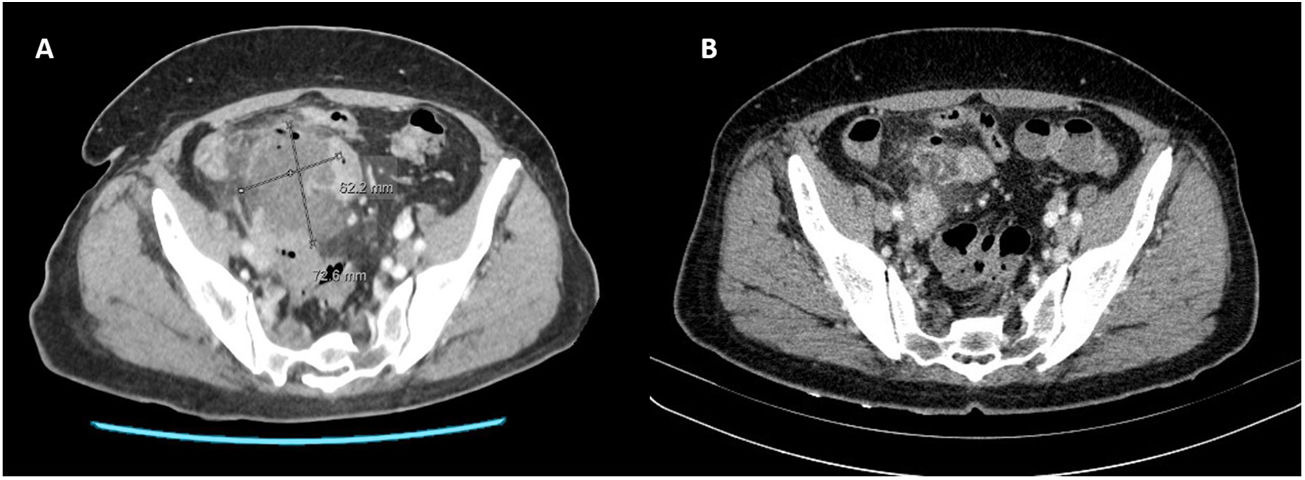

Given the epidemiological situation and compatible symptoms, a chest X-ray was performed in the emergency department as part of the pandemic protocol, which showed bilateral opacities compatible with COVID-19. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and lymphopenia and increased lactate dehydrogenase 270IU/L, C-reactive protein (CRP) 291.1mg/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase 265 IU/L, ferritin (663ng/mL) and d-dimer (2.422ng/mL). Given the findings, a nasopharyngeal RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was ordered, which was positive, and the patient was hospitalized in the Internal Medicine ward. After 2 days, and given the persistence of abdominal pain, a CT scan was ordered, which revealed complicated acute appendicitis with an inflammatory mass measuring 6.2×7.3×6cm and radiological signs of moderate COVID-19 lung involvement (Fig. 1). Given the findings, the patient was evaluated by General Surgery (2 days after admission). The case was discussed in the Interventional Radiology service to assess the placement of a percutaneous drain, but this was ruled out because the collection was not organized.

After joint evaluation, we decided to maintain admission to the Internal Medicine ward for management of COVID-19 and conservative treatment of the plastron appendicitis.5 The patient received treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for 5 days (in accordance with the COVID-19 hospital protocol at that time) and ceftriaxone for 2 days. After establishing the diagnosis of complicated acute appendicitis, broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment (piperacillin-tazobactam) was prescribed, ultimately completing a 10-day cycle.

From a respiratory standpoint, the patient required oxygen therapy with nasal cannulae at 2 L for the first 2 days; this was later able to be withdrawn, maintaining baseline oxygen saturations >95%. From the abdominal point of view, she progressed favorably with less pain and was able to initiate oral intake progressively.

Prior to discharge, a follow-up CT scan (9 days after the initial one) showed persistence of bilateral mild/moderate pulmonary involvement (slight improvement) and a clear improvement in radiological findings compatible with complicated acute appendicitis, observing a significant decrease in the size of the collection (1.4×2cm) (Fig. 2).

Likewise, follow-up lab studies showed an improvement in acute-phase reactants, although the following parameters remained high: d-dimer (870ng/mL), gamma-glutamyl transferase (256IU/L), lactate dehydrogenase (215IU/L) and PCR (17.2mg/L).

Given the good clinical–analytical–radiological evolution, the patient was discharged after 11 days of hospitalization with instructions to isolate at home, oral antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for 5 more days, and a telephone follow-up after one month, with a good, sustained evolution. After this episode, a follow-up colonoscopy will be performed, and elective appendectomy will be considered. It is important to highlight the association found between patients who begin with complicated acute appendicitis/inflammatory mass and a possible tumor.6

In conclusion, the great variability of symptoms of COVID-19 disease makes it necessary to rule out underlying pathology, especially in patients with predominant abdominal symptoms. Since the availability of operating rooms has been reduced and the surgical treatment of a SARS-CoV-2-positive patient may pose an added risk,7 conservative treatment has been considered in those pathologies where it is safe and feasible.8,9 Nevertheless, patients should always be treated individually and closely monitored to detect unfavorable progression.

Please cite this article as: Vicario Bravo M, Chavarrías Torija N, Rubio-Pérez I. Sintomatología digestiva y COVID-19: importancia de descartar patología quirúrgica asociada. Cir Esp. 2021;99:385–387.