Undetected spinal injuries after trauma can cause severe neurologic sequelae. After an initial trauma that is considered not serious, the appearance of neurological symptoms in the following days should alert us to the presence of a possible spinal injury. A careful medical history that includes inquiry about any possible history of trauma, together with a proper physical examination, should guide us toward rare entities that could potentially be very serious without appropriate treatment, such as this case we present.

The patient is a 40-year-old man with a history of behavioral disturbances and substance abuse, who came to the emergency department reporting progressive symptoms of hand weakness and gait disturbance over the previous 3–4 days. He had suffered moderate-energy left posterolateral blunt trauma associated with forced cervical rotation during an assault two weeks earlier, for which he did not visit the emergency department (thus, the initial injuries were not evaluated by a healthcare professional at that time). After an asymptomatic period of time, he developed progressive symptoms of predominantly distal weakness in both upper limbs. He was currently unable to open his hands and had a sensation of electrical shocks and cramping, especially in the left upper limb ipsilateral to the trauma. He also described a feeling of oppression in the form of a belt in the abdominal region and numbness in both upper extremities. The symptoms progressed and, in the 24h prior to consultation, he began having difficulty walking and experienced a loss of strength in the lower limbs. He also reported left posterolateral cervical pain radiating to the ipsilateral upper limb.

Physical examination revealed a fever of 38°C, with no swelling or hematoma in the area of the trauma, tetraparesis grade 4/5 (strength against resistance, without full strength), predominantly distal in the upper limbs (strength grade 2/5 in finger extension, not being able to extend the fingers against gravity) and proximal in the lower limbs, with bilateral extensor plantar response (injury to the bilateral pyramidal pathway). Likewise, we observed a D7–D8 touch-pain sensory level, absence of cutaneous-abdominal reflexes, inability to walk without assistance and pareto-ataxic gait (due to injury to the pyramidal motor pathway and impaired deep sensitivity/sensory ataxia) with bilateral support.

Lab work-up showed elevated acute-phase reactants with normal leukocyte formula. Chest radiograph ruled out upper thoracic injuries. Cervical radiography was not performed. Urgent magnetic resonance imaging (Figs. 1 and 2) revealed a lesion with an extensive paravertebral, retrovertebral and intracanal spinal component that caused C6–C7 cord compression (incipient compressive myelopathy), partially surrounding the brachial plexus and extending caudally to at least the D2 vertebra. These findings suggested the presence of a superinfected paravertebral hematoma and an epidural abscess, with no component of bone involvement, suggesting a tuberculous origin.

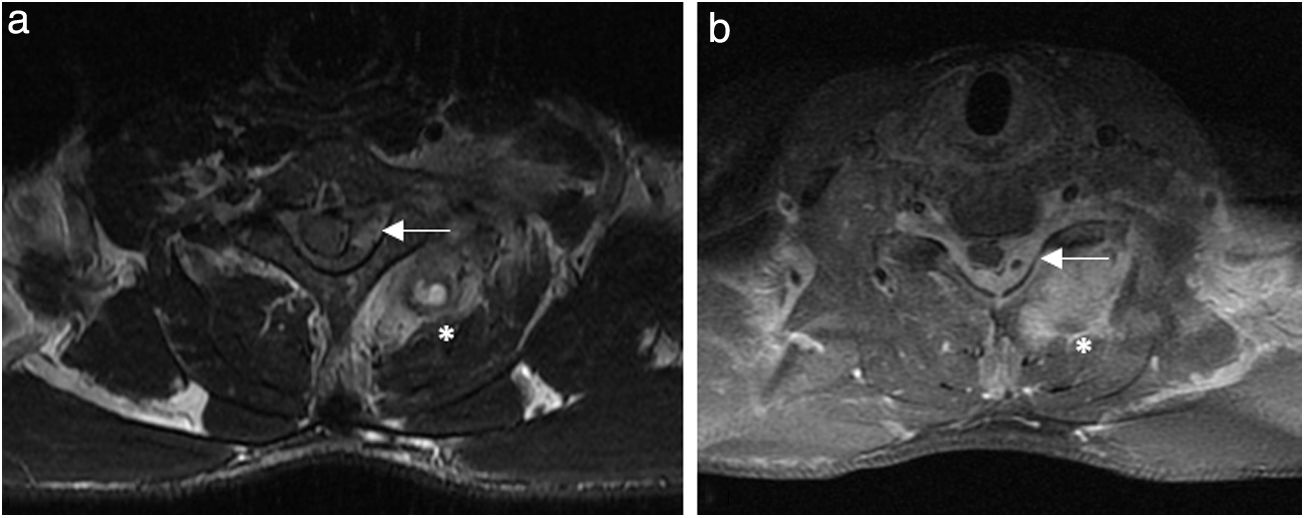

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): (a) weighted axial image in T2 at the level of the C6/C7 intervertebral space; (b) weighted in T1 at the C7 intervertebral space, revealing an inflammatory/infectious process with microabscesses (*) of the left paravertebral muscles (semispinalis capitis, spinalis cervicis and multifidus muscles) and occupation of the spinal canal by a left epidural abscess resulting in contralateral displacement of the spinal cord (⟵).

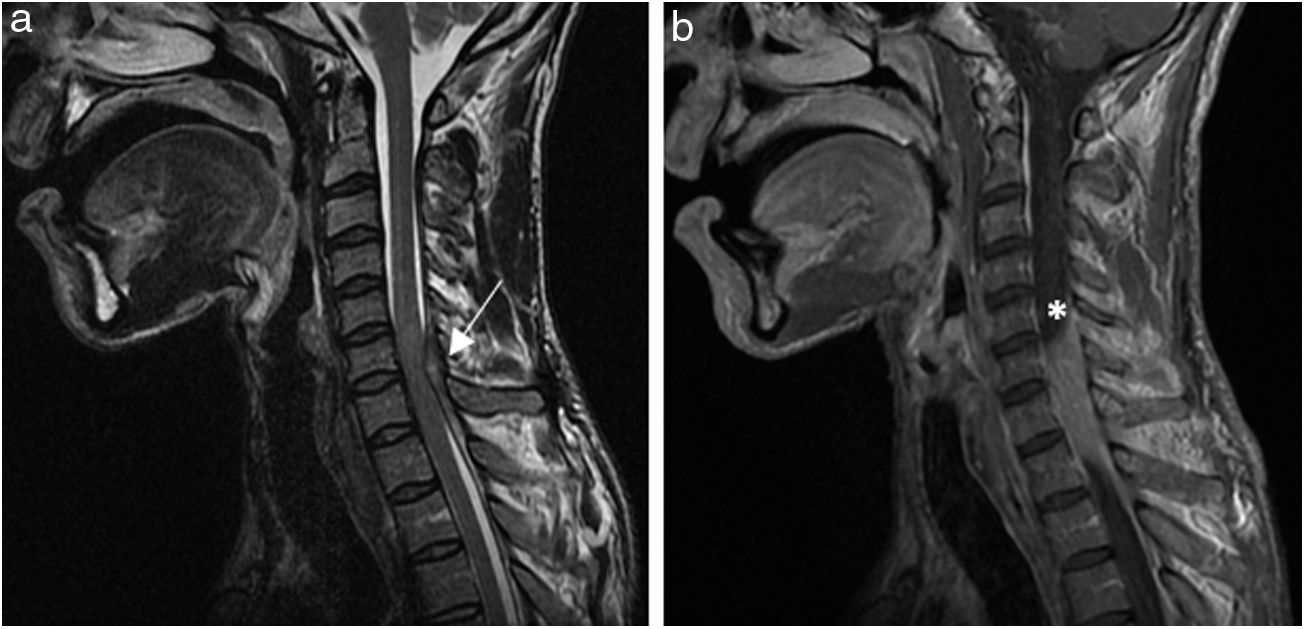

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): (a) weighted sagittal image in T2 of the cervical region demonstrating the presence of an epidural abscess at C6–C7–T1, occupying the spinal canal, and change in the spinal cord signal compatible with associated compressive myelopathy (⟵); (b) weighted sagittal image in T1 of the cervical region demonstrating the left posterolateral epidural collection (*) and obliteration of the subarachnoid space at this level.

Given these radiological findings and the patient's symptoms, immediate surgical treatment was indicated, with evacuation of the epidural abscess and the infectious/inflammatory process in the soft tissue, in association with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. After surgery, the patient presented progressive improvement of the neurological symptoms and was able to walk independently with unilateral support on the 5th postoperative day, showing no signs of sepsis. The pathological study of the sample obtained in the operating room revealed findings compatible with abscess, and the tuberculous origin was ruled out. The microbiological study confirmed the presence of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Spinal epidural abscess is rare, although its incidence is on the rise due to the greater prevalence of risk factors, such as intravenous drug use, immunosuppression, and spinal surgery.1,2 The origin associated with contiguous infection of a soft tissue hematoma after a trauma injury is also possible.3 The classic triad of fever, pain, and neurological deficit is only seen in 10% of patients.4 The prognosis is ominous (with severe neurological sequelae in up to one-third of survivors, sepsis and even death), and the outcome is directly related to whether treatment is early.2,5,6

The appearance of neurological symptoms after cervical trauma makes it necessary to rule out spinal-cord injury in the secondary evaluation of trauma patients,7 even when the trauma was considered non-serious. However, there is sometimes a symptom-free period after the trauma (open or closed). The appearance of delayed neurological symptoms after an apparently trivial trauma should not be underestimated as it may indicate a severe neurological injury, such as the one described in this case due to spinal cord injury, as well as the presence of a dural fistula.8 Both pathologies can have dire consequences if they go unnoticed or if treatment is not started immediately after the onset of symptoms.9 Urgent neurosurgical consultation should not be delayed in these cases, and transfer of the patient to a referral center should be considered at the time of diagnosis if necessary.

The presence of subacute or delayed neurological symptoms in a patient who has had blunt cervical trauma, although it was not high-energy and does not present data of vertebral fracture, requires urgent differential diagnosis with post-traumatic spinal cord injuries.

Please cite this article as: Ginestal-López RC, Gómez-Iglesias P, García-Yepes M, Yus-Fuertes M, Fernández García C. Lesión espinal subaguda: la importancia del antecedente traumático. Cir Esp. 2021;99:387–389.