Projectile embolisation, secondary to firearm injuries to the peripheral vascular tree, is an extremely rare condition. It involves elevated mortality and risk for loss of an extremity1–3 if diagnosis and treatment are delayed.2

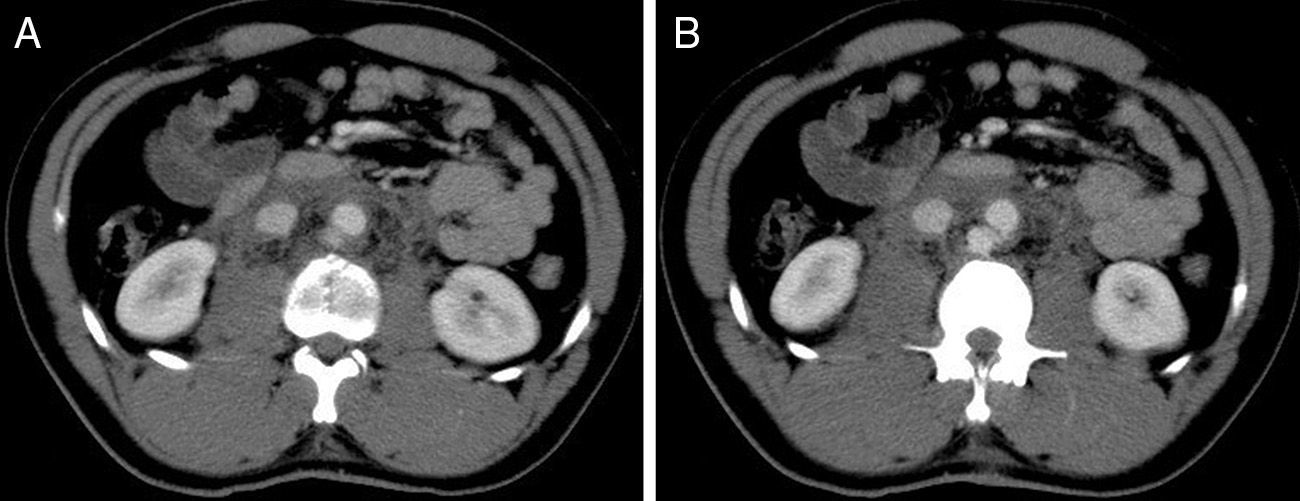

The patient is a 26-year-old male who came to the Emergency Room at our hospital due to a firearm injury in the lumbar area. He presented with an entry orifice in the left paraspinal region at L3, with no signs of active bleeding or an exit orifice. Examination revealed psychomotor agitation, blood pressure 110/60mmHg and reported pain in the lower extremities with slight functional impotence and bilateral coldness. We observed the absence of distal pulses in the lower left extremity (LLE). Given the relative haemodynamic stability, thoracoabdominal/pelvis computed tomography angiography3 was ordered, which showed evidence of an entry pathway and fracture of the L3 vertebra (Fig. 1A), with no compromise of the spinal canal; there was perforation on the posterior side of the aorta at this level, with active bleeding that was contained by the retroperitoneum4 (Fig. 1B). No organ injuries were observed, and the projectile was not visualised.

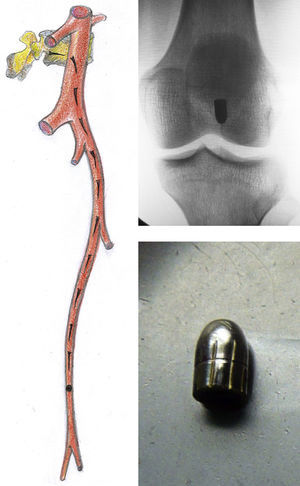

The patient was immediately taken to surgery; using midline laparotomy, and after aortic clamping, we proceeded with simple suture of the posterior wall of the aorta (lateral aortorrhaphy).4 After a detailed examination of the abdominal cavity, the bullet was not found, and no signs of other intraabdominal lesions detected. As there was no exit wound, and given the absence of distal pulse in the LLE, we initiated a radioscopy-guided search and located the projectile in the left popliteal fossa (Fig. 2). The presumed migration pathway of the bullet was through the infrarenal aorta, left iliac artery, common and superficial femoral arteries to the left popliteal artery. After a failed attempt at transfemoral extraction due to the impaction of the bullet in the midsection of the popliteal artery, we dissected the proximal and distal portions of the artery medially1,2 and extracted the foreign body with forceps (projectile measured 6.35mm). The arteriotomies were closed with continuous suture and the laparotomy was closed. In the postoperative period, bilateral paraparesis persisted and was more pronounced in the right extremity, in association with intense hyperalgesia and persistence of the occlusion of the distal trunks in LLE, with no other associated signs of ischaemia. The later progress of the patient's condition was favourable, with progressive improvement of the paraparesis after rehabilitation and, 6 months later, the patient is able to walk with a cane.

The presentation of arterial firearm injury and later intravascular migration of the projectile is a very rare complication in vascular trauma and its presence in the literature is limited to the presentation of case reports. It was described for the first time by Davis in 1843 and represents only 0.3% of firearm-related vascular trauma.1 Penetration and later intravascular migration depend on the size and kinetic energy (Ek) of the bullet. The trajectory through the skin, fascia, muscle, and bone tissue disperses the Ek, allowing for penetration but not perforation of the bullet. Once inside the vascular tree, the Ek of the blood flow is greater than that of the projectile, and its journey begins.5 Therefore, low-velocity bullets that are small in size and mass (Ek=mv2) are more likely to migrate within the blood vessels. The ammunition involved in this case was small calibre (6.35mm or 0.25″), which lost most of its Ek upon impacting and fracturing the vertebra. To the contrary, large-calibre ammunition travelling at high speed is highly unlikely to cause an intravascular embolism. The ensuing migration and final destination of the bullet depends on the calibre, patient vascular anatomy, haemodynamics, body position and gravitational effects,2 although the embolism is almost twice as likely to occur through the left iliac artery1 because of the angle of the aortic bifurcation.6 Complications of the distal embolism will depend on the level of occlusion, collaterality, time transpired before diagnosis and the formation of a secondary thrombosis.1 Some 80% of patients will have symptoms related to the ischaemia, which should not be confused with or attributed to spinal cord injuries,1,4 as could have happened in our case.

Peripheral embolisation should be suspected when there is no exit orifice, the projectile is not detected with standard imaging techniques nor found along the expected trajectory, or when there are signs of peripheral vascular involvement.1,7 The examination of the extremities and peripheral pulses is required in any vascular trauma.6

In conclusion, penetrating trauma of the abdominal aorta presents high mortality and, when associated with the rare condition of peripheral arterial embolism, there is also a risk of limb loss. A high clinical suspicion provides early diagnosis and treatment, which contribute to the survival of the patient and the extremity.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare having no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Stefanov Kiuri S, Fernández Heredero Á, Herrera Sampablo AI, Riera del Moral L, Riera de Cubas L. Herida por arma de fuego y embolismo arterial periférico. Cir Esp. 2015;93:e111–e113.