Activated carbon (AC) is the treatment of choice for acute gastrointestinal poisoning.1 It usually has few complications, especially when administered according to its indications for use.2 Among these are the risk/benefit assessment of its administration3 according to the potential toxicity resulting from the type and dose of the ingested product and, above all, the patient's clinical condition to minimize the risk of pulmonary aspiration,4 which is the most frequent complication, although not the only one.5

The patient is a 53-year-old male who had been transferred from another hospital to our centre for psychiatric assessment after a suicide attempt by the ingestion of multiple medications (200mg escitalopram, 3mg bromazepam and 6mg lormetazepam) approximately 16h before. His personal history included anxiety-depressive disorder (under treatment) and 2 previous suicide attempts, one of them by ingesting a caustic substance 18 months before.

Upon arrival at our ER, the patient had a 0.5cm nasogastric tube in place, through which he had been administered AC. Physical examination detected an abdomen with generalized guarding and peritoneal irritation. Chest radiograph showed the existence of pneumoperitoneum, which was confirmed on abdominal CT scan. Given these findings, we proceeded with laparoscopic surgery. We found an important diffuse biliary peritonitis as well as a dark free fluid corresponding with the AC that had been administered. A 0.5cm prepyloric gastric perforation was identified, which was treated with primary closure and the placement of a Graham patch. The abdominal cavity was washed abundantly and a suction drain was inserted.

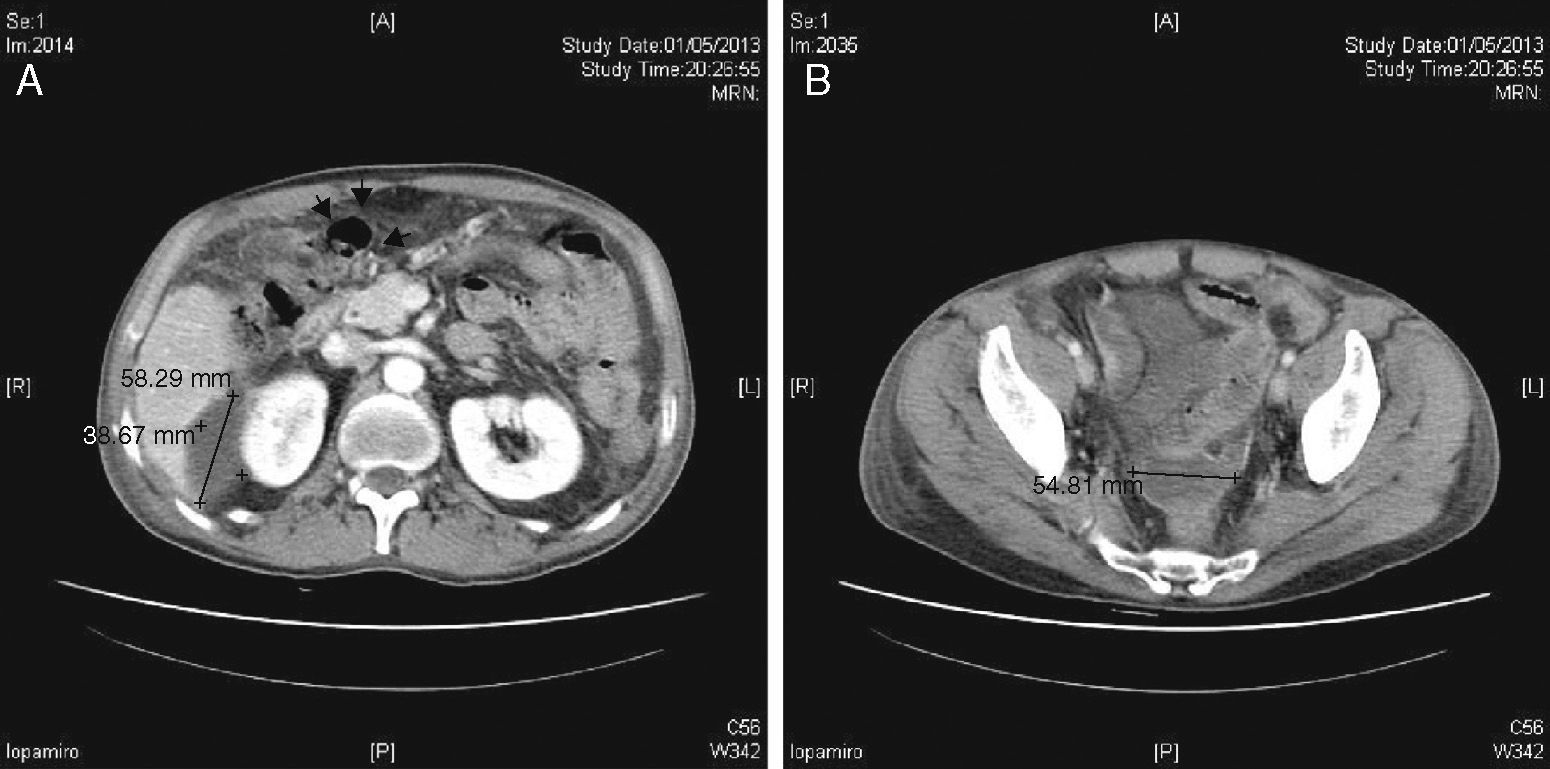

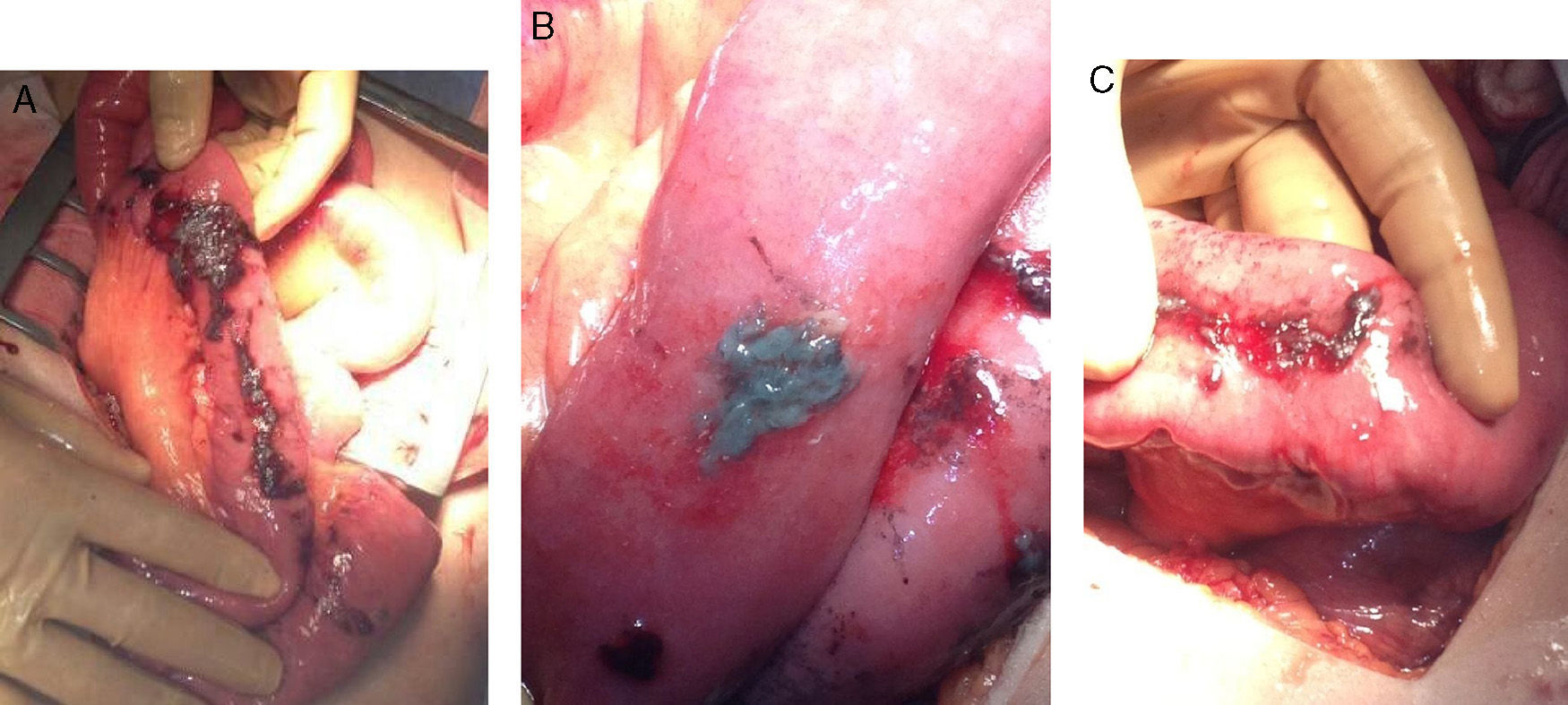

During the initial post-op, the patient presented favourable progress. On the 8th day, he began to have intense pain in the right hypochondrium with observed guarding on examination and signs of peritoneal irritation. Another CT scan showed multiple encapsulated intraabdominal collections (Fig. 1A and B). Laparotomy revealed chemical peritonitis with multiple AC plaques disseminated in the abdominal cavity (Fig. 2A) on the bowel loops, mesentery, liver surface, omentum, pelvic peritoneum, etc. (Fig. 2B). When the plaques from the bowel loops were partially removed, we observed how they had caused superficial ulcers on the intestinal serosa, which was very fragile (Fig. 2C). The previous surgery was reviewed, and no new perforation was found. In addition, we observed right subphrenic abscess with a chocolate-like purulent content as well as a pelvic abscess with a large number of AC plaques at the base of the recto-vesical pouch. We proceeded with aspiration of the abscesses and thorough washing of the cavity. Likewise, the entire small bowel was checked, from the Treitz angle to the cecum, and no bowel perforations were observed. Once again, suction drains were inserted and we proceeded with closure. The patient progressed favourably and was discharged 10 days after the second procedure.

In the review of the literature, we have only found 2 cases of gastrointestinal perforation due to nasogastric catheter placement for decontamination with AC. Cravat et al. presented a case of oesophageal perforation after multiple orogastric catheterisation attempts, which resulted in pneumomediastinum with passage of carbon to the posterior mediastinum.6 In the case by Mariani and Pook, after orogastric tube insertion, pneumoperitoneum was observed 3h later; during laparotomy, abundant AC was observed in the peritoneum, although no interruption was found in the digestive tract that would have caused the migration of AC to the peritoneal cavity.7 In our case, the juxtapyloric perforation was probably related with duodenal fibrosis vs an old duodenal ulcer, secondary to the patient's prior ingestion of a caustic substance, which would have favoured perforation during nasogastric tube placement.

Our patient required a second surgical procedure to extract AC, even after having performed abundant peritoneal lavage during the first surgery. In the case described by Mariani and Pook, the patient required for the same reason 2 new laparotomies on days 10 and 16 after the initial surgical intervention. During the latter, AC was found on the right ovary.7 These surgical findings and the clinical progress in both cases indicate that AC in the abdominal cavity has a great ability to adhere to abdominal organs, causing adhesions between bowel loops that result in closed cavities susceptible to infection.7

Furthermore, this adhesion of AC is so intense that, in our opinion, care must be taken when removing the plaques from the loops as there is a risk for iatrogenic intestinal perforation. The fragility observed in the underlying serosa is probably secondary to the absorptive capacity or the chemical interaction between AC and the intestinal wall. Therefore, initial surgical procedures of the extraction of intraperitoneal AC should be centred on thorough washing of the abdominal cavity7 and close postoperative patient monitoring because of the probable appearance of recurring chemical peritonitis. During re-operation, secondary abscesses should be sought.

Finally, we should emphasize the fact that gastrointestinal decontamination with AC in cases of poisoning can also be done by ingestion of AC, and tube insertion is not required for its administration in conscious patients.1,8,9 This is able to reduce the risk for iatrogenic gastrointestinal perforation and complications10 like those described in this case.

Please cite this article as: Lobo-Machin I, Medina-Arana V, Delgado-Plasencia L, Bravo-Gutiérrez A, Burillo-Putze G. Peritonitis por carbón activado. Cir Esp. 2015;93:e107–e109.