Hepatobronchial fistulae (HBF) are rare entities. They are defined as abnormal communications of a sector of liver parenchyma with a sector of the bronchial tree through a diaphragmatic pathway. First described by Peacock in 1850 in a patient with a hepatic hydatid cyst and hydatid vomica, its frequency has decreased, mainly due to the use of antibiotics in the presence of hepatic abscesses and the surgical treatment of hepatic and pulmonary hydatid cysts.1

HBF may be congenital or acquired. Acquired HBF (80%) is mainly caused by hepatic hydatid cysts that migrate toward the pleural cavity through the diaphragm. The other 20% are due to hepatic abscesses (amebic or pyogenic), lithiasis of the biliary tract and, less frequently, as a result of surgery or liver trauma.2,3

Bronchobiliary fistulae (BBF) are those in which part of the biliary tract communicates with the bronchial tree, thereby perpetuating the pathway.4 In these cases, the diagnosis is made more easily because the patient has a productive cough with biliary sputum (which characteristically stains the teeth yellow) in association with fever and leukocytosis.

HBF that do not communicate with the bile duct, which are generally secondary to hepatic abscesses, are rarer. They do not present the characteristic bilioptysis, but instead purulent bronchorrhea, fed by the hepatic abscess. HBF usually appear in the context of a florid infection, with fever and leukocytosis, abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium and occasionally pleuritic pain and cough. They may present dyspnea of varying magnitudes and jaundice in some cases.5

The diagnosis is complemented with radiography and computed tomography (CT) studies. Therapeutic approaches range from conservative to minimally invasive to radical surgery (thoracic or thoracoabdominal), with diverse results.6

Below, we present a case of HBF that was diagnosed and resolved by our department.

The patient is a 70-year-old man who underwent urgent surgery for acute cholecystitis. Surgery was initiated with a laparoscopic approach, which had to be converted to open surgery due to technical difficulties given the intense inflammatory process. There were no intraoperative incidents, patient progress was good, and antibiotic treatment was followed for 7 days.

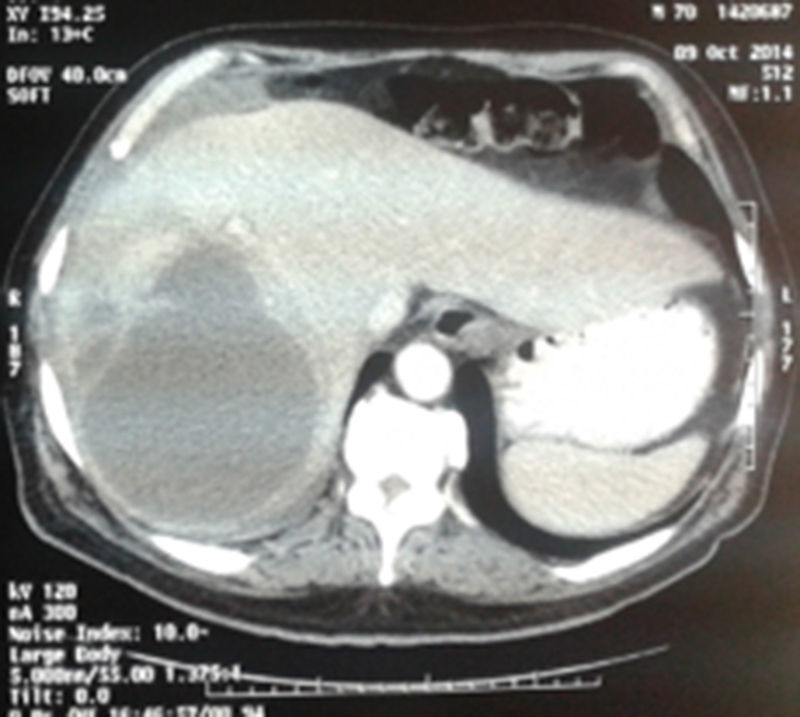

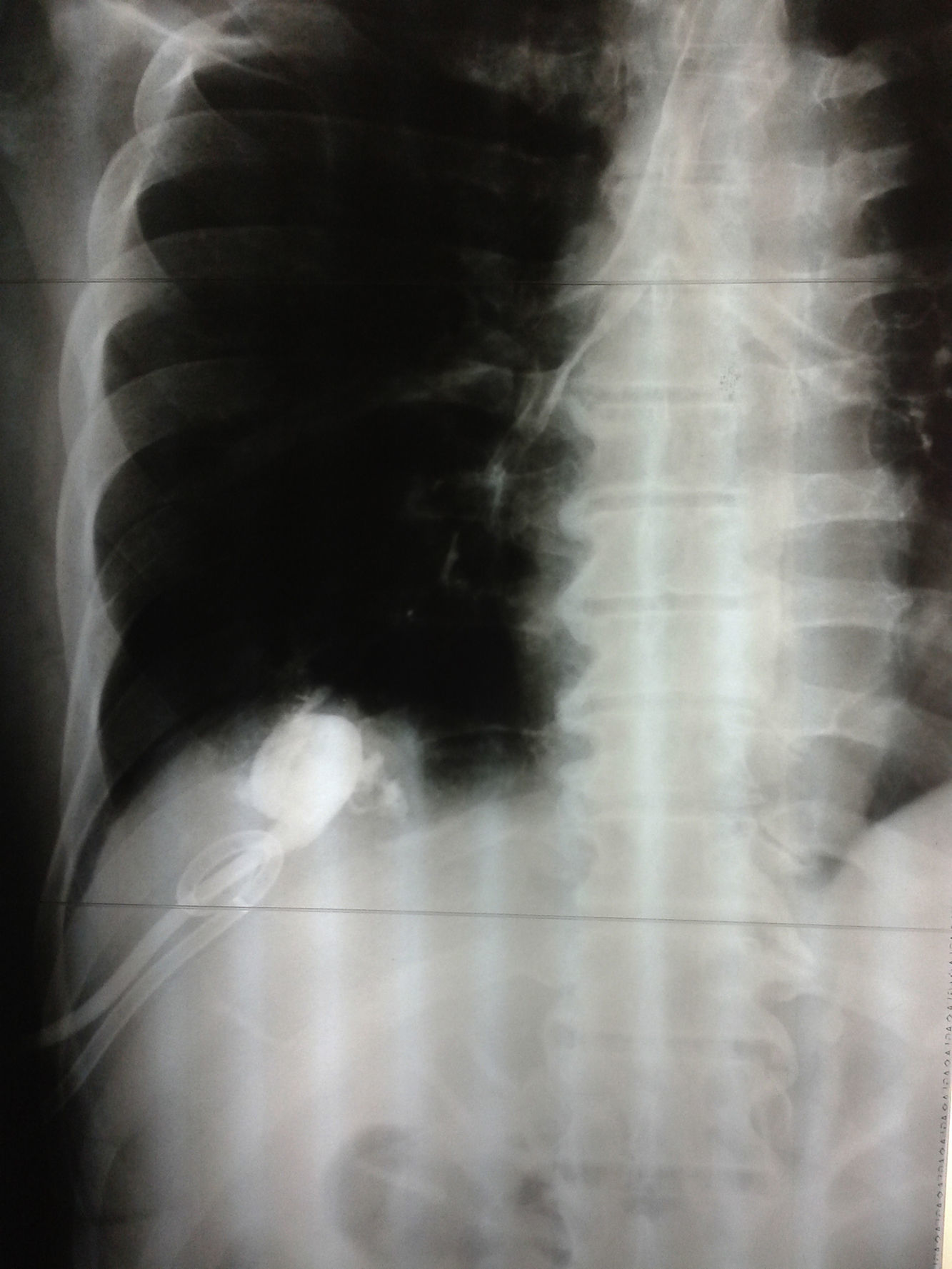

The patient was re-hospitalized 40 days later with cough, abundant purulent bronchorrhea that was brown in color, and fever. Laboratory tests showed: 17000leukocytes/mm3, prothrombin time 53% and hemoglobin 9.2mg/dL. Chest radiograph showed evidence of inhomogeneous occupation of the right lung base. The patient presented respiratory insufficiency secondary to severe pneumonia; he was admitted to the ICU and thoracic and abdominal CT scans were ordered. The CT scans showed a heterogeneous collection in the hepatic dome (segments 7 and 8) that was 11–12cm in diameter and compatible with abscess, a focal right basal consolidation and a moderate amount of pleural fluid (Fig. 1).

Treatment with ciprofloxacin and intravenous metronidazole was initiated empirically. We performed ultrasound-guided percutaneous puncture of the hepatic abscess, placing a 12Fr Dawson Müller-type drain tube and obtaining 300–400mL of brownish pus with the same characteristics as the patient's bronchorrhea. We observed that lavage of the abscess caused cough, which, together with the patient's surgical history and imaging studies, led us to the diagnosis of hepatobronchial fistula. The evidence of contrast material in the airway after instillation through the hepatic drain tube supported our diagnosis (Fig. 2). A pleural drainage tube was placed, which produced little turbid discharge that disappeared within 24h.

The culture of the pus was positive for Escherichia coli, which was sensitive to the previously prescribed antibiotics. The pleural drainage catheter was removed after 3 days. The hepatic drains produced no bilious content; they were washed out daily, and their discharge was zero on the sixth day, so they were withdrawn. Follow-up CT scans after 1 and 6 months demonstrated resolution of the abscess and fistula.

We present a case of HBF as an unusual complication after urgent cholecystectomy, which is a frequent procedure. Although the diagnosis is more evident when the patient has bilioptysis, in cases in which there is no biliary communication the diagnosis is more difficult. A CT scan is the first imaging study to be done since it can define the outline of the liver abscess and assess any pulmonary involvement.3 Ultrasound has a high sensitivity for defining hepatic lesions, and in this case it guided the evacuation puncture of the abscess. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography may be useful to detect the fistula tract in cases of bronchobiliary communication.5 There was no need for ERCP in our patient, since there was no bile duct lithiasis.

Traditionally, drainage of hepatic abscesses has been proposed, which was performed by means of open surgery in the era prior to percutaneous techniques, and perhaps pulmonary resection if the lung damage is considered irreversible, leaving in pleural and subdiaphragmatic drain tubes.3,6,7 Adequate antibiotic treatment is essential, and it is likewise necessary to verify the permeability of the bile duct.2,7 The advent of minimally invasive percutaneous techniques has allowed us to resolve the majority of cases that present with hepatic abscesses with less parietal aggression, as in the case of our patient.

Please cite this article as: Varela Vega M, Durán F, Geribaldi N, San Martín G, Ettlin A. Fístula hepatobronquial: una rara complicación de un absceso hepático. Cir Esp. 2017;95:410–411.