Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (IPEH), or Masson's tumor, is a rare benign intravascular lesion. It is a reactive process in the context of venous stasis, in which there is a proliferation of endothelial papillary structures that are organized around thrombi.1–3

It was first described in 1923 by Masson4 as an endothelial papillary hyperplasia in the lumen of hemorrhoidal veins, and was considered a vascular neoplasm, termed “vegetant intravascular hemangioendothelioma”. In 1932, Henschen5 observed that it is a reactive process, not an endothelial neoplasm, therefore renaming it L’endovasculite proliferante thrombopoietique. In 1976, Clearkin and Enzinger suggested that thrombosis precedes endothelial proliferation, and the thrombotic material constitutes a matrix for its development.2 After several studies, it was verified that the lesion was a vascular proliferation secondary to venous stasis. In 1990 and based on immunohistochemical studies, Albrecht and Kahn described a similar progression between endothelial hyperplasia and thrombosis.6 Both are positive for ferritin, histiocytic markers and, eventually, vimentin in the early stages, while at the end of the process they are only positive for factor VIII antigen.

Masson's tumors mainly affect the head and neck vessels, fingers, trunk and skin veins, while abdominal involvement is exceptional. Only one case of hepatic involvement has been reported in the literature.7

We present the case of a 39-year-old male, with no medical history of interest, who was asymptomatic. During routine examination, hepatomegaly was detected upon abdominal palpation; ultrasound demonstrated a 10cm lesion suggestive of hemangioma.

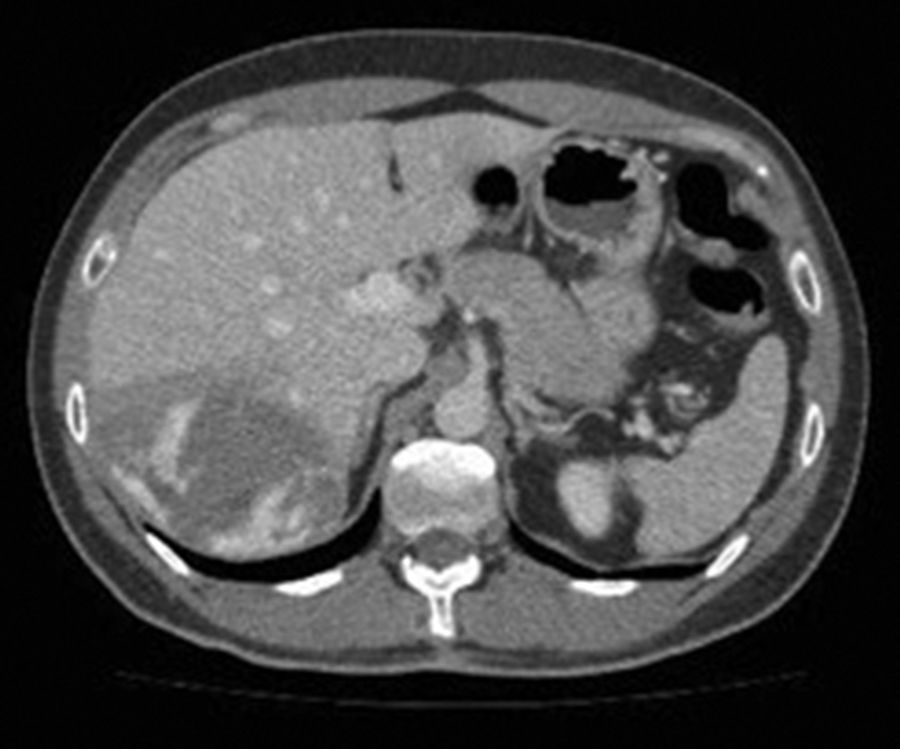

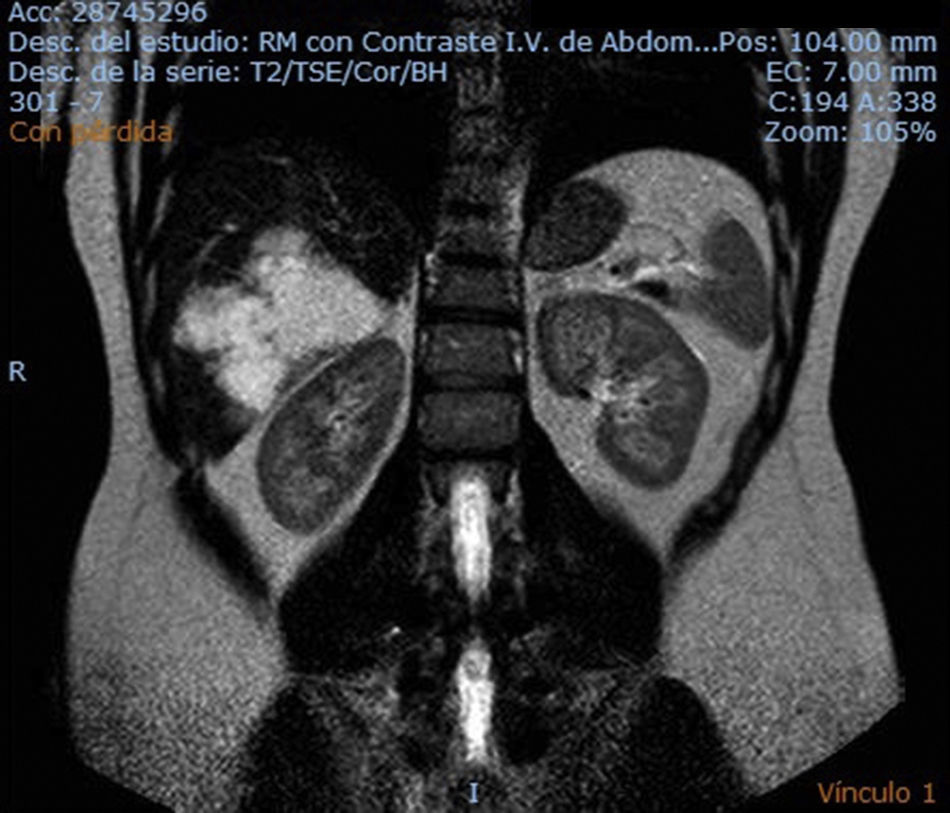

The study was completed with an abdominal CT scan, MRI and tumor marker study. The CT scan showed a lesion measuring 10×9.5×7cm occupying segments VI and VII, which was hypodense and had lobed edges. Contrast uptake by the peripheral nodes and centripetal filling, without complete filling of the lesion, were suggestive of hemangioma (Fig. 1). MRI detected a lesion the same size as CT, with lobed edges and central areas of necrosis; peripheral uptake and centripetal filling were compatible with hemangioma. No pathological tumor marker alterations were observed (Fig. 2).

During follow-up, the patient presented abdominal discomfort secondary to the lesion size, although there were no apparent changes to the lesion. After assessing the case in committee, surgery was indicated, and an atypical segmentectomy was conducted of segments VI and VII. The postoperative period transpired without incident; the patient progressed favorably and was discharged on the 5th postoperative day. During outpatient follow-up, there were no incidents in the first year after surgery.

The pathology report identified a 170g fragment measuring 12×9cm that, after serial sections, was identified as a poorly defined, sponge-like, purplish subcapsular lesion measuring 10×7cm, inside of which a 4×3cm whitish, well-defined fleshy area was found. Microscopically, a benign vascular process was identified with endothelial proliferation in the small and medium-sized vessel lumens, compatible with Masson's tumor.

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia is a rare benign condition requiring differential diagnosis, primarily with hemangiosarcoma. Initially, it was considered a malignant disease, and Masson described it as a neoplasm secondary to the degeneration of a venous thrombosis.4 However, after several studies, it was demonstrated that Masson tumors consist of a proliferation of endothelial cells that are organized around thrombi, thereby becoming established as a reactive process in the context of venous stasis.1–3

Histopathologically, 3 forms have been described1,8: the “pure” form, which is most frequent, appears de novo in the dilated vascular spaces in patients without comorbidities and without vascular abnormalities; the “mixed” form, which appears in vessels with abnormalities such as arteriovenous malformations, hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomatosis and chronic diseases such as paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; and, finally, the “extravascular” form, which is associated with trauma-related hematomas.

The development of intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia takes place in several stages. In the early stages, there is endothelial cell growth within the thrombus. These cells begin to proliferate and secrete collagenases, which partially and irregularly digest the thrombus, developing papillary structures. Finally, these papillary structures combine to form anastomosed vascular structures.9

The most frequent locations are the vessels of the head and neck, fingers, trunk and cutaneous veins. Intra-abdominal lesions are rare, and even rarer are those in the liver.

Epidemiologically, a slightly higher incidence has been observed in women than in men, with a ratio of 1.2: 1, with no predilection for age. Cases have been reported in patients ranging from 7 months to 81 years of age.1

Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia is an uncommon disease that can simulate other diseases. It is therefore necessary to carry out a detailed differential diagnosis, and the definitive diagnosis is often reached by the pathology study.

Treatment of IPEH depends on its location and, considering that it is a benign disease, the symptoms that it causes. In general, surgical resection is the treatment of choice for IPEH as it provides a very good prognosis and very low recurrence rate (mainly in the mixed and extravascular forms).10 Surgery is considered curative in the pure forms when the margins of the surgical specimen are free, with low reported rates of recurrence in the mixed and extravascular forms.

FundingThe authors have received no public or private funding for the completion of this article.

Please cite this article as: Ramallo Solís I, Tinoco González J, Senent Boza A, Bernal Bellido C, Gómez Bravo MÁ. Tumor de Masson intrahepático (hiperplasia endotelial papilar intravascular). Cir Esp. 2017;95:235–237.