After 20 years of experience in laparoscopic liver surgery there is still no clear definition of the best approach (totally laparoscopic [TLS] or hand-assisted [HAS]), the indications for surgery, position, instrumentation, immediate and long-term postoperative results, etc.

AimTo report our experience in laparoscopic liver resections (LLRs).

Patients and methodOver a period of 10 years we performed 132 LLRs in 129 patients: 112 malignant tumours (90 hepatic metastases; 22 primary malignant tumours) and 20 benign lesions (18 benign tumours; 2 hydatid cysts). Twenty-eight cases received TLS and 104 had HAS. Surgical technique: 6 right hepatectomies (2 as the second stage of a two-stage liver resection); 6 left hepatectomies; 9 resections of 3 segments; 42 resections of 2 segments; 64 resections of one segment; and 5 cases of local resections.

ResultsThere was no perioperative mortality, and morbidity was 3%. With TLS the resection was completed in 23/28 cases, whereas with HAS it was completed in all 104 cases. Transfusion: 4.5%; operating time: 150min; and mean length of stay: 3.5 days. The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates for the primary malignant tumours were 100, 86 and 62%, and for colorectal metastases 92, 82 and 52%, respectively.

ConclusionLLR via both TLS and HAS in selected cases are similar to the results of open surgery (similar 5-year morbidity, mortality and survival rates) but with the advantages of minimally invasive surgery.

Tras 20 años de experiencia en cirugía hepática laparoscópica, aún no están bien definidos el mejor abordaje (totalmente laparoscópico [CTL] o asistido con la mano [CLA]), indicaciones quirúrgicas, posición, instrumentación, resultados postoperatorios inmediatos y a largo plazo, etc.

ObjetivoPresentar nuestra experiencia en resecciones hepáticas laparoscópicas (RHL).

Pacientes y métodoEn 10 años hemos realizado 132 RHL en 129 pacientes: 112 tumores malignos (90 metástasis hepáticas; 22 tumores malignos primarios) y 20 lesiones benignas (18 tumores benignos; 2 quistes hidatídicos). Veintiocho casos se realizaron por CTL y 104 por CLA. Técnica quirúrgica: 6 hepatectomías derechas (2 como segundo tiempo de una resección hepática en 2 tiempos); 6 hepatectomías izquierdas; 9 resecciones de 3 segmentos; 42 resecciones de 2 segmentos; 64 resecciones de un segmento y 5 casos de resecciones locales.

ResultadosNo existió mortalidad perioperatoria. Morbilidad: 3%. Con CTL se completó la resección en 23/28 casos, mientras que con CLA se completó en los 104 casos. Transfusión 4,5%; tiempo quirúrgico 150min y estancia media de 3,5 días. La supervivencia a 1, 3 y 5 años de los tumores malignos primarios fue del 100, 86 y 62%, mientras que la supervivencia de las metástasis colorrectales fue del 92, 82 y 52%, respectivamente.

ConclusiónLa RHL, tanto por CTL como por CLA, en casos seleccionados, reproduce los resultados de la cirugía abierta (morbimortalidad y supervivencia a 5 años similares), con las ventajas de la cirugía mínimamente invasiva.

The current indications for laparoscopic liver surgery (LLS), tumours less than 5cm located in the left anatomic lobe of the liver or in the anterior segment, were outlined in 2000,1 and these indications were re-established in the Louisville meeting2 in 2009. More complex laparoscopic liver resections (LLR) (e.g., posterior-superior segments, central tumours, proximity to large vessels, and major resections) should be performed in centres with experience in such procedures.3–7 The 2 fundamental approaches for LLR are total laparoscopic surgery (TLS)1,4,6 and assisted laparoscopic surgery (ALS),4,5,7,8 and a variety of factors, including the surgeon, pathology, lesion size, and the location of lesions, dictate procedure selection.

This article presents our experience with LLS using 2 laparoscopic approaches, TLS and ALS, and it presents the indications, advantages and disadvantages of both techniques. We also present the post-operative outcomes of our LLR series, which is the largest published series in our country.

Patients and MethodsWe performed 683 liver resections between January 2003 and April 2012; 132 (19.3%) of these resections were LLR performed in 129 patients (2 LLR were performed in one patient, and resection was performed in 2 stages in 2 patients). LLR was performed in 5.5% of cases in 2003 (3/54 cases) and 23.3% of cases in 2011 (21/90 cases). The median patient age was 62 years (range 23–85), and 54 patients were women (42%).

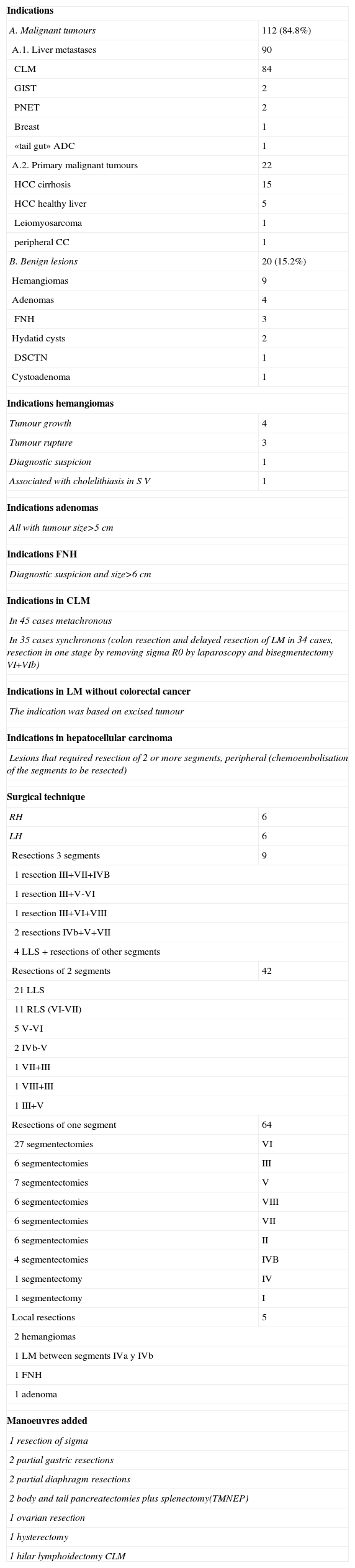

The indication for LLR in 112 cases (85%) was a malignant tumour (Table 1): 90 liver metastases and 22 primary liver tumours. The remaining 20 resections (15%) were benign lesions: 18 benign tumours and 2 hydatid cysts.

Indications and Surgical Technique (n=132).

| Indications | |

| A. Malignant tumours | 112 (84.8%) |

| A.1. Liver metastases | 90 |

| CLM | 84 |

| GIST | 2 |

| PNET | 2 |

| Breast | 1 |

| «tail gut» ADC | 1 |

| A.2. Primary malignant tumours | 22 |

| HCC cirrhosis | 15 |

| HCC healthy liver | 5 |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 1 |

| peripheral CC | 1 |

| B. Benign lesions | 20 (15.2%) |

| Hemangiomas | 9 |

| Adenomas | 4 |

| FNH | 3 |

| Hydatid cysts | 2 |

| DSCTN | 1 |

| Cystoadenoma | 1 |

| Indications hemangiomas | |

| Tumour growth | 4 |

| Tumour rupture | 3 |

| Diagnostic suspicion | 1 |

| Associated with cholelithiasis in S V | 1 |

| Indications adenomas | |

| All with tumour size>5cm | |

| Indications FNH | |

| Diagnostic suspicion and size>6cm | |

| Indications in CLM | |

| In 45 cases metachronous | |

| In 35 cases synchronous (colon resection and delayed resection of LM in 34 cases, resection in one stage by removing sigma R0 by laparoscopy and bisegmentectomy VI+VIb) | |

| Indications in LM without colorectal cancer | |

| The indication was based on excised tumour | |

| Indications in hepatocellular carcinoma | |

| Lesions that required resection of 2 or more segments, peripheral (chemoembolisation of the segments to be resected) | |

| Surgical technique | |

| RH | 6 |

| LH | 6 |

| Resections 3 segments | 9 |

| 1 resection III+VII+IVB | |

| 1 resection III+V-VI | |

| 1 resection III+VI+VIII | |

| 2 resections IVb+V+VII | |

| 4 LLS+resections of other segments | |

| Resections of 2 segments | 42 |

| 21 LLS | |

| 11 RLS (VI-VII) | |

| 5 V-VI | |

| 2 IVb-V | |

| 1 VII+III | |

| 1 VIII+III | |

| 1 III+V | |

| Resections of one segment | 64 |

| 27 segmentectomies | VI |

| 6 segmentectomies | III |

| 7 segmentectomies | V |

| 6 segmentectomies | VIII |

| 6 segmentectomies | VII |

| 6 segmentectomies | II |

| 4 segmentectomies | IVB |

| 1 segmentectomy | IV |

| 1 segmentectomy | I |

| Local resections | 5 |

| 2 hemangiomas | |

| 1 LM between segments IVa y IVb | |

| 1 FNH | |

| 1 adenoma | |

| Manoeuvres added | |

| 1 resection of sigma | |

| 2 partial gastric resections | |

| 2 partial diaphragm resections | |

| 2 body and tail pancreatectomies plus splenectomy(TMNEP) | |

| 1 ovarian resection | |

| 1 hysterectomy | |

| 1 hilar lymphoidectomy CLM | |

ADC: adenocarcinoma; CC: cholangiocarcinoma; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; GIST: gastrointestinal stroma tumour; RH: Right hepatectomy; LH: Left hepatectomy; FNH: focal nodular hyperplasia; CLM: colorectal liver metastasis; DSCTN: desmoplastic spindle cell tumour in nests; PNET: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour; RLS: right lateral segmentectomy; LLS: left lateral segmentectomy.

We resected 203 liver lesions, and 42 of these cases exhibited 2 or more lesions (32%) with an average tumour size of 4.8cm (range 1–20cm). Lesions were localised in the right posterior-superior segments of the liver (VII and VIII) in 34 of these cases (26%). LLR was performed for the first time for the treatment of multiple bilobar colorectal liver metastases (CLM) in 4 cases: 2 cases underwent percutaneous portal vein embolisation 1 week before a right hepatectomy was completed via laparoscopy, and CLM was performed via laparotomy in the other 2 cases.

We employed TLS and ALS according to the following criteria:

- -

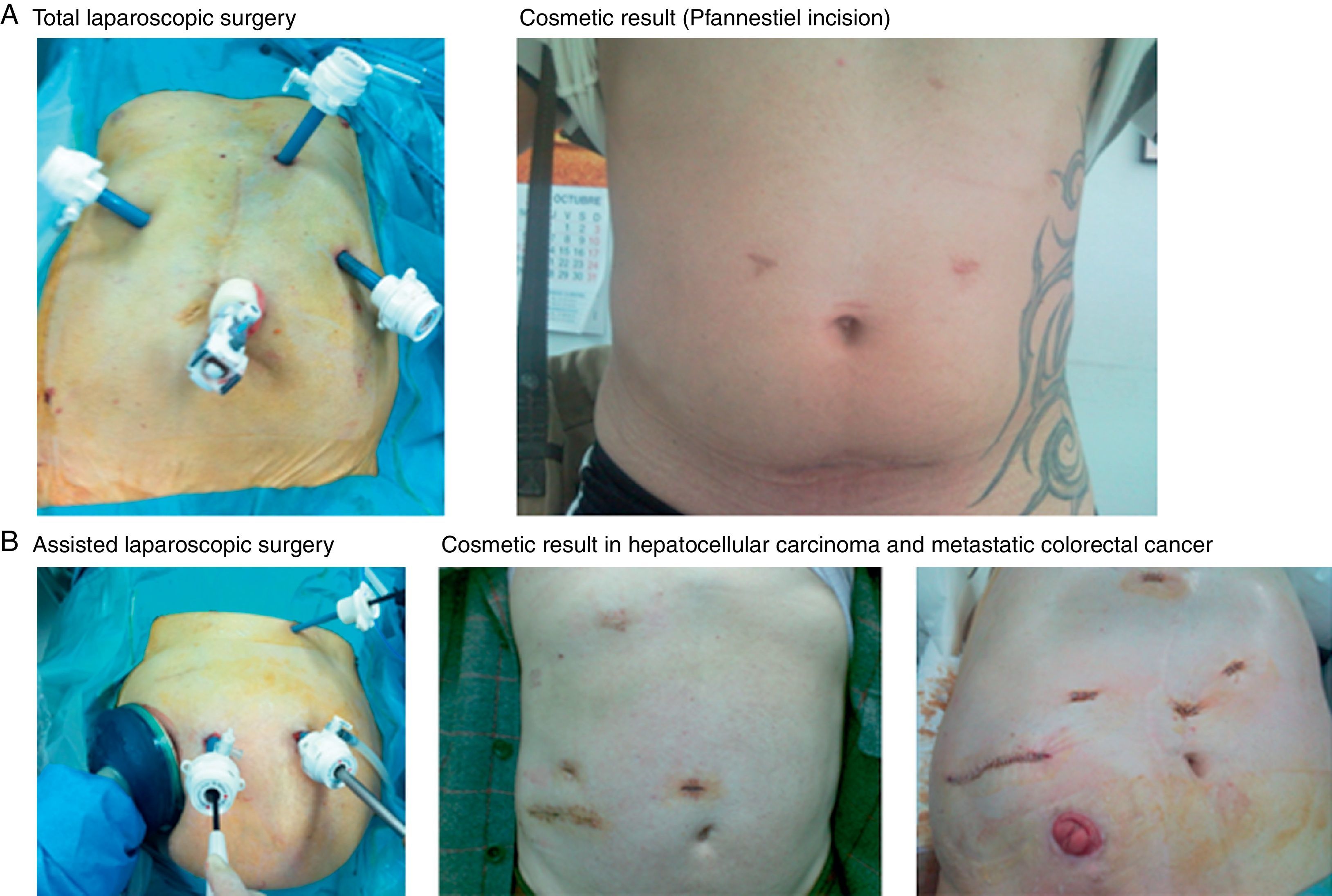

TLS (28 cases): TLS was indicated in 13 benign tumours, 11 hepatocellular carcinomas in cirrhotic livers, 3 hepatocellular carcinomas in healthy livers and 1 peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. The patient was placed in a supine position, and the surgeon stood between the patient's legs with 2 assistants. Three trocars were placed following a concave line to the lesion (one trocar is 12mm when an endovascular stapler is used) (Fig. 1A) to generate a pneumoperitoneum of 12mmHg. Another 3 optional trocars could be placed if necessary: in the epigastrium for liver retraction, in the right subcostal area to mobilise the right lobe and in the left flank to introduce the clamp used to perform the Pringle manoeuvre (described by our unit).9,10 We used an optic of 0° and a flexible laparoscopic ultrasound 5.5–7.5MHz, Philips©. Sectioning of the parenchyma was performed using a harmonic scalpel (Ethicon©), and the intrahepatic vessels were dissected with clips or hemolocks. The hepatic hilum was occluded using a LigaSure Atlas® (Covidien©). We transected the hepatic artery and portal vein in the portal pedicles with ligatures or hemolocks in right and left lobe dissections, and the biliary tract was transected with staples. The suprahepatic veins were dissected and transected with staples. Hemostasis of the liver surface was performed using Tissuelink® (Primm©), and bile leaks were sutured. Hemostatic material was placed on the liver surface (TachoSil®-Nycomed©), and non-aspiration drainage was placed when necessary. The resected specimens are placed in a bag and removed through a Pfannenstiel incision.

- -

ALS (104 cases): ALS was indicated in 90 cases of liver metastases (LM) of correct staging: 6 for large tumours (2 benign and 4 malignant primary tumours between 7 and 20cm); 6 for tumours in the right posterior segment (5 large benign tumours of 5cm and one hepatocellular carcinoma); and 2 cases converted from TLS to ALS. We employed the technique originally described and published by our unit9,10 (Fig. 1B), which is briefly described here. A transverse incision was made in the right flank from the mid-axillary line to the anterior axillary line, where a handport was placed (GelPort®; Applied Medical©). A full manual examination of the liver and abdominal cavity was performed, and an abdominal ultrasound (Entos®, CT8, Philips©) exploration was performed introduced through the handport. The remainder of the procedure was similar to the procedure for TLS. The resected liver specimen was placed in a bag and removed via the handport.

We performed 21 major resections (16%): 6 right hepatectomies, 6 left hepatectomies and 9 resections of 3 segments (Table 1). Intraoperative radiofrequency ablation was used in 7 patients (2 for the treatment of cirrhotic nodules, 2 to treat CLM of 1cm size, and 3 to ensure that the surgical margin was clear after the resection of CLM). Additional procedures following LLR were performed in 10 patients (Table 1). The anaesthetic and central venous pressures (CVP) are identical to the parameters of open surgery (CVP below 4).

We calculated the overall survival and disease-free rates at 1, 3 and 5 years using the Kaplan–Meier method. Comparisons of means between groups were performed using the Student t-test or the Behrens–Fisher test, depending on the homogeneity of variances between samples, or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test. We compared percentages between groups with analysis of contingency tables using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test when case frequencies were low.

ResultsNo intra- or post-operative deaths occurred. Complications occurred in 4 cases (3%) (2 cases with collections requiring radiological-guided drainage: 1 case of a biliary fistula and 1 case of sepsis due to an infected collection, both cases required reoperation). Transfusions were required in 4.5% of cases (6 patients), and the median operative time was 150min (range 60–360min). The average hospital stay was 3.5 days (range 2–30 days). The Pringle manoeuvre was used in 44 cases (33.3%) with a median time of 16min (range 6–21min): hemi-hepatic occlusion was performed in 12 cases, 2 cases underwent selective hepatic artery and right portal vein occlusion, and the remaining 74 resections were performed without vascular occlusion.

Three TLS cases were converted to laparotomy (2.3%): 1 case of haemorrhage of a liver adenoma 8cm in size in segment VII and 2 cases of CLM due to blocking adhesions with an accidental perforation of a small bowel loop. TLS resection was completed in 23 of 28 cases (82%): besides the 3 cases converted to laparotomy, 2 cases were converted to ALS. ALS laparoscopic resection was completed in 104 cases.

ALS was used to resect CLM that were first staged using ultrasound, visualisation of the abdominal cavity and palpation within a prospective comparative study between both staging methods. Eighty-four LR were performed for CLM: 77 were staged (liver resection was performed in 2 stages in 2 patients, and 2 patients who were conversions from TLS to laparotomy and 3 resections in cirrhotic livers were excluded). The addition of palpation detected more disease than ultrasound examination alone in 8 patients (10%) and a peritoneal implant was detected in one of these cases.

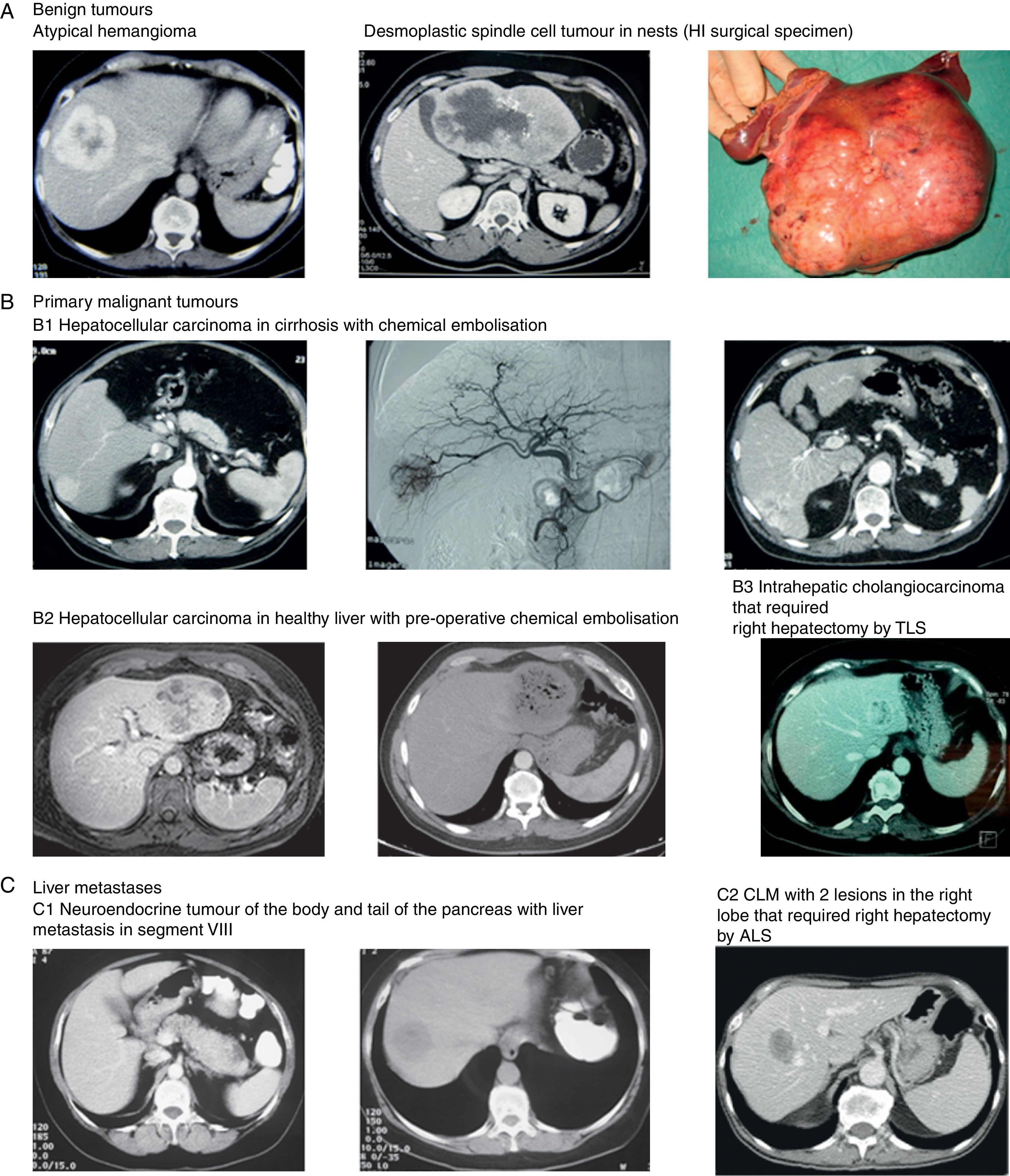

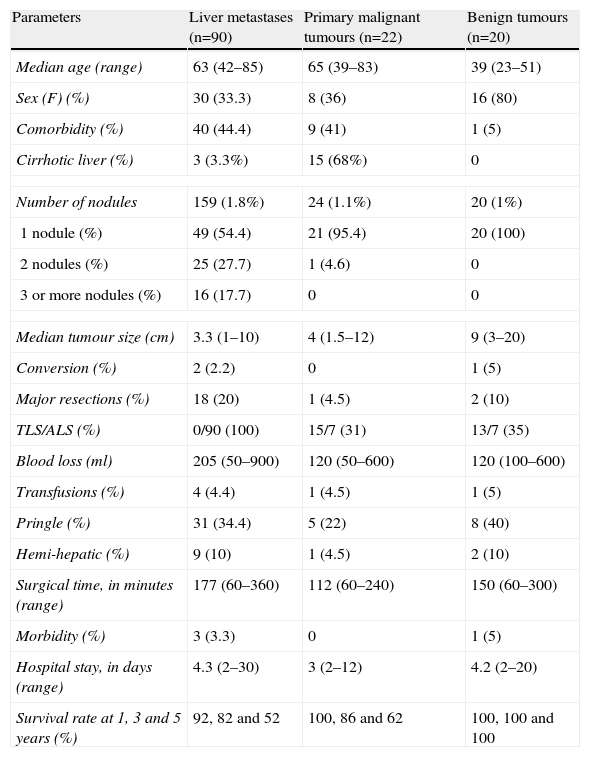

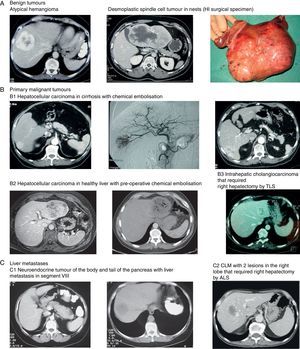

Age and comorbidity for benign tumours (Table 2) (Fig. 2A, 2) were lower than in the LM and primary malignant tumours (Fig. 2B, 1, 2 and 3), and tumour size and the percentage of women was higher (P<.05). Blood loss, operating time and the number of nodules were higher in LM (Fig. 2C, 1, 2) than in other indications (16 patients had 3 or more lesions), and surgical margins invaded further into the parenchyma in 3 patients. Overall survival and disease-free survival at 1, 3 and 5 years of CLM were 92, 82 and 52% and 85, 60 and 32%, respectively. The number of cirrhotic livers in primary malignant tumours was higher, and there were fewer major resections than in the other 2 groups. Blood loss, the use of the Pringle manoeuvre, operative time, hospital length of stay and morbidity were lower in the other 2 groups. Overall survival and disease-free rates at 1, 3 and 5 years was 100, 86 and 62% and 94, 80 and 50%, respectively.

Results of Laparoscopic Liver Surgery According to the Surgical Indication: Liver Metastases, Primary Malignant Tumours and Benign Tumours.

| Parameters | Liver metastases (n=90) | Primary malignant tumours (n=22) | Benign tumours (n=20) |

| Median age (range) | 63 (42–85) | 65 (39–83) | 39 (23–51) |

| Sex (F) (%) | 30 (33.3) | 8 (36) | 16 (80) |

| Comorbidity (%) | 40 (44.4) | 9 (41) | 1 (5) |

| Cirrhotic liver (%) | 3 (3.3%) | 15 (68%) | 0 |

| Number of nodules | 159 (1.8%) | 24 (1.1%) | 20 (1%) |

| 1 nodule (%) | 49 (54.4) | 21 (95.4) | 20 (100) |

| 2 nodules (%) | 25 (27.7) | 1 (4.6) | 0 |

| 3 or more nodules (%) | 16 (17.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Median tumour size (cm) | 3.3 (1–10) | 4 (1.5–12) | 9 (3–20) |

| Conversion (%) | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Major resections (%) | 18 (20) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (10) |

| TLS/ALS (%) | 0/90 (100) | 15/7 (31) | 13/7 (35) |

| Blood loss (ml) | 205 (50–900) | 120 (50–600) | 120 (100–600) |

| Transfusions (%) | 4 (4.4) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (5) |

| Pringle (%) | 31 (34.4) | 5 (22) | 8 (40) |

| Hemi-hepatic (%) | 9 (10) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (10) |

| Surgical time, in minutes (range) | 177 (60–360) | 112 (60–240) | 150 (60–300) |

| Morbidity (%) | 3 (3.3) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Hospital stay, in days (range) | 4.3 (2–30) | 3 (2–12) | 4.2 (2–20) |

| Survival rate at 1, 3 and 5 years (%) | 92, 82 and 52 | 100, 86 and 62 | 100, 100 and 100 |

ALS: assisted laparoscopic surgery; TLS: Total laparoscopic surgery; F: female.

Images of some tumours in our series. (A) Benign tumours. (1) Atypical hemangioma. (2 and 3) Desmoplastic spindle cell tumour in nests (HI surgical specimen). (B) Primary malignant tumours. (1) Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis with chemical embolisation (2) Hepatocellular carcinoma in healthy liver with pre-operative chemical embolisation (3) Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma that required right hepatectomy by TLS. (C) Liver metastases. (1) Neuroendocrine tumour of the body and tail of the pancreas with liver metastasis in segment VIII. (2) CLM with 2 lesions in the right lobe that required right hepatectomy by ALS.

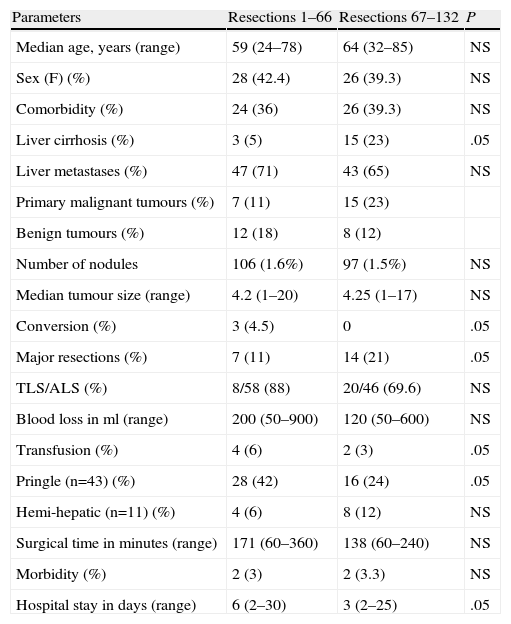

More cirrhotic livers were observed in the final 66 resections (Table 3) than in the first 66 resections, and no patients were converted to laparotomy. We have conducted more major hepatic resections with a decrease in blood loss, transfusions, Pringle manoeuvres, operating time and hospital stay with increased experience.

Results Obtained by Comparing the First 61 Resections With the Second 62 Resections.

| Parameters | Resections 1–66 | Resections 67–132 | P |

| Median age, years (range) | 59 (24–78) | 64 (32–85) | NS |

| Sex (F) (%) | 28 (42.4) | 26 (39.3) | NS |

| Comorbidity (%) | 24 (36) | 26 (39.3) | NS |

| Liver cirrhosis (%) | 3 (5) | 15 (23) | .05 |

| Liver metastases (%) | 47 (71) | 43 (65) | NS |

| Primary malignant tumours (%) | 7 (11) | 15 (23) | |

| Benign tumours (%) | 12 (18) | 8 (12) | |

| Number of nodules | 106 (1.6%) | 97 (1.5%) | NS |

| Median tumour size (range) | 4.2 (1–20) | 4.25 (1–17) | NS |

| Conversion (%) | 3 (4.5) | 0 | .05 |

| Major resections (%) | 7 (11) | 14 (21) | .05 |

| TLS/ALS (%) | 8/58 (88) | 20/46 (69.6) | NS |

| Blood loss in ml (range) | 200 (50–900) | 120 (50–600) | NS |

| Transfusion (%) | 4 (6) | 2 (3) | .05 |

| Pringle (n=43) (%) | 28 (42) | 16 (24) | .05 |

| Hemi-hepatic (n=11) (%) | 4 (6) | 8 (12) | NS |

| Surgical time in minutes (range) | 171 (60–360) | 138 (60–240) | NS |

| Morbidity (%) | 2 (3) | 2 (3.3) | NS |

| Hospital stay in days (range) | 6 (2–30) | 3 (2–25) | .05 |

ALS: assisted laparoscopic surgery; TLS: Total laparoscopic surgery; F: female.

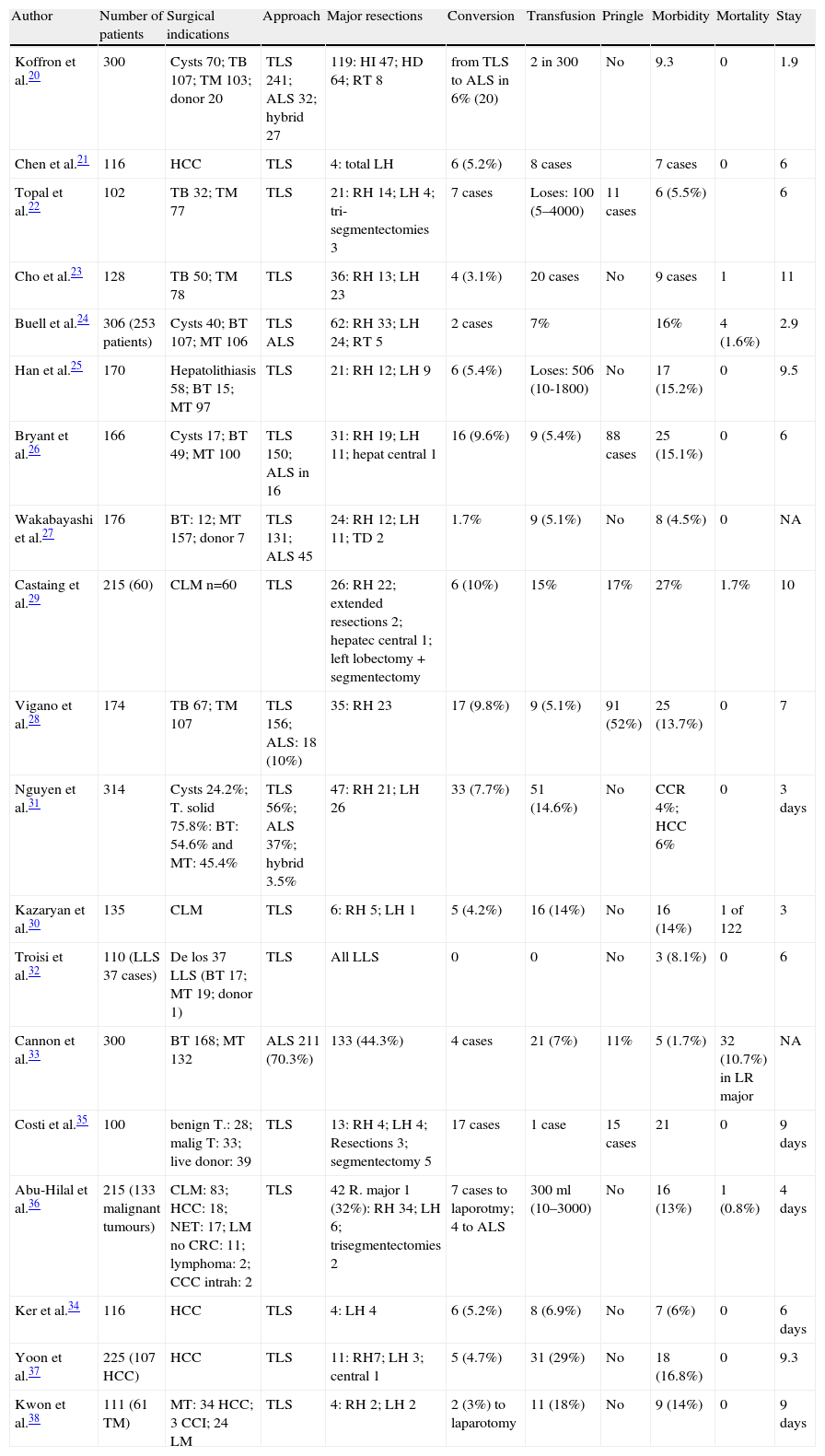

We initiated LLS of cystic liver lesions in 199311 within the context of our overall experience in general laparoscopic surgery.12–15 We began LLR in January 2003 after we acquired experience in open liver surgery (177 resections). Three LLR series have been published in Spain, and all of these studies include less than 100 cases.16–18 One national multicentric study examined 104 LLR of solid lesions in 15 centres.19 Recent institutional studies have included more than 100 LLR (Table 4),20–38 and recent reviews of almost 3000 patients39–50 have attempted to verify the safety (morbidity) and curative efficacy compared to open surgery.

Series With Over 100 Laparoscopic Liver Resections (Excluding Meta-analyses, Reviews and Multicentric Studies).

| Author | Number of patients | Surgical indications | Approach | Major resections | Conversion | Transfusion | Pringle | Morbidity | Mortality | Stay |

| Koffron et al.20 | 300 | Cysts 70; TB 107; TM 103; donor 20 | TLS 241; ALS 32; hybrid 27 | 119: HI 47; HD 64; RT 8 | from TLS to ALS in 6% (20) | 2 in 300 | No | 9.3 | 0 | 1.9 |

| Chen et al.21 | 116 | HCC | TLS | 4: total LH | 6 (5.2%) | 8 cases | 7 cases | 0 | 6 | |

| Topal et al.22 | 102 | TB 32; TM 77 | TLS | 21: RH 14; LH 4; tri-segmentectomies 3 | 7 cases | Loses: 100 (5–4000) | 11 cases | 6 (5.5%) | 6 | |

| Cho et al.23 | 128 | TB 50; TM 78 | TLS | 36: RH 13; LH 23 | 4 (3.1%) | 20 cases | No | 9 cases | 1 | 11 |

| Buell et al.24 | 306 (253 patients) | Cysts 40; BT 107; MT 106 | TLS ALS | 62: RH 33; LH 24; RT 5 | 2 cases | 7% | 16% | 4 (1.6%) | 2.9 | |

| Han et al.25 | 170 | Hepatolithiasis 58; BT 15; MT 97 | TLS | 21: RH 12; LH 9 | 6 (5.4%) | Loses: 506 (10-1800) | No | 17 (15.2%) | 0 | 9.5 |

| Bryant et al.26 | 166 | Cysts 17; BT 49; MT 100 | TLS 150; ALS in 16 | 31: RH 19; LH 11; hepat central 1 | 16 (9.6%) | 9 (5.4%) | 88 cases | 25 (15.1%) | 0 | 6 |

| Wakabayashi et al.27 | 176 | BT: 12; MT 157; donor 7 | TLS 131; ALS 45 | 24: RH 12; LH 11; TD 2 | 1.7% | 9 (5.1%) | No | 8 (4.5%) | 0 | NA |

| Castaing et al.29 | 215 (60) | CLM n=60 | TLS | 26: RH 22; extended resections 2; hepatec central 1; left lobectomy+segmentectomy | 6 (10%) | 15% | 17% | 27% | 1.7% | 10 |

| Vigano et al.28 | 174 | TB 67; TM 107 | TLS 156; ALS: 18 (10%) | 35: RH 23 | 17 (9.8%) | 9 (5.1%) | 91 (52%) | 25 (13.7%) | 0 | 7 |

| Nguyen et al.31 | 314 | Cysts 24.2%; T. solid 75.8%: BT: 54.6% and MT: 45.4% | TLS 56%; ALS 37%; hybrid 3.5% | 47: RH 21; LH 26 | 33 (7.7%) | 51 (14.6%) | No | CCR 4%; HCC 6% | 0 | 3 days |

| Kazaryan et al.30 | 135 | CLM | TLS | 6: RH 5; LH 1 | 5 (4.2%) | 16 (14%) | No | 16 (14%) | 1 of 122 | 3 |

| Troisi et al.32 | 110 (LLS 37 cases) | De los 37 LLS (BT 17; MT 19; donor 1) | TLS | All LLS | 0 | 0 | No | 3 (8.1%) | 0 | 6 |

| Cannon et al.33 | 300 | BT 168; MT 132 | ALS 211 (70.3%) | 133 (44.3%) | 4 cases | 21 (7%) | 11% | 5 (1.7%) | 32 (10.7%) in LR major | NA |

| Costi et al.35 | 100 | benign T.: 28; malig T: 33; live donor: 39 | TLS | 13: RH 4; LH 4; Resections 3; segmentectomy 5 | 17 cases | 1 case | 15 cases | 21 | 0 | 9 days |

| Abu-Hilal et al.36 | 215 (133 malignant tumours) | CLM: 83; HCC: 18; NET: 17; LM no CRC: 11; lymphoma: 2; CCC intrah: 2 | TLS | 42 R. major 1 (32%): RH 34; LH 6; trisegmentectomies 2 | 7 cases to laporotmy; 4 to ALS | 300ml (10–3000) | No | 16 (13%) | 1 (0.8%) | 4 days |

| Ker et al.34 | 116 | HCC | TLS | 4: LH 4 | 6 (5.2%) | 8 (6.9%) | No | 7 (6%) | 0 | 6 days |

| Yoon et al.37 | 225 (107 HCC) | HCC | TLS | 11: RH7; LH 3; central 1 | 5 (4.7%) | 31 (29%) | No | 18 (16.8%) | 0 | 9.3 |

| Kwon et al.38 | 111 (61 TM) | MT: 34 HCC; 3 CCI; 24 LM | TLS | 4: RH 2; LH 2 | 2 (3%) to laparotomy | 11 (18%) | No | 9 (14%) | 0 | 9 days |

CCC: cholangiocarcinoma; ALS: assisted laparoscopic surgery; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; RH: right hepatectomy; LH: left hepatectomy; CLM: colorectal liver metastases; NO not obtainable; LLS: left lateral sectionectomy; BT: benign tumours; RT: right trisectomectomy; MT: malignant tumours; NET: neuroendocrine tumours.

Many authors, especially in Europe,1,6,16,17,26–30,35,36 prefer TLS and reserve ALS for conversion. However, 42 of 103 resections (40.4%) in a review of LLR by CLM were performed using ALS, and it was more frequently used in American centres (85%) than European (15%).31,42 The Louisville meeting concluded that ALS is quick, safe and most likely more effective than TLS for LM, and it highlighted the high rate of TLS use in the U.S.2,41 and Japan.38 A problem of TLS in CLM is the possibility of failure to detect occult lesions using laparoscopic ultrasound examination. This problem has been demonstrated in several studies in which the addition of liver palpation in staging detected liver disease and/or inadvertent peritoneal lesions in 10%–20% of cases when converting to laparotomy or ALS.8,51–53 Our results in CLM demonstrate under-staging in 10% of cases, which suggests that palpation is essential for proper staging.53

TLS is the indicated approach in primary malignant tumours because they are often unique surgeries, and palpation is ineffective for the adequate staging of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic livers. Staging must be performed with ultrasound alone in these cases (in our series, there were 15 out of 22 cases by TLS). TLS of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis may reduce postoperative ascites due to the preservation of the collateral circulation.16,17,21,28,34,37 We use pre-operative chemical embolisation of the segments to be resected54 to decrease the amount of haemorrhage and the need for the Pringle manoeuvre. This technique may also ensure the surgical margin because most of the chemically embolised nodules exhibited greater than 90% necrosis.

Benign tumours are a good indication for LLS because these patients are young and present with solitary tumours (Table 2) and the cosmetic result is important. TLS is the ideal approach because the resected liver is extracted through a Pfannenstiel incision, and this approach was performed in 13 of 20 of our patients. ALS may be an alternative start for large tumours and/or localisation in posterior segments of the right lobe5,8,10,18,20,21,31 or after conversion from TLS. TLS has not changed the indication of benign tumours in our unit, and this procedure was used for 6% of all solid tumours that were resected until January 2003 and 7.5% since that date. However, benign tumours account for 20%–50% of the indications in some series.19,20,26

The size and localisation of lesions are important for the selection of patients for LLS.4,5,10,16–18,20,23,24,31 In our series, 36 patients (25%) had tumours larger than 5cm. Additionally, the difficulties are even greater if these large lesions are located in posterior segments (as occurred in 9 of the 34 patients with tumours in that location), and some surgeons advocate placing the patient in the lateral decubitus position.1,16,17,28,33 However, ALS in supine patients has expanded the initially recommended indications for some authors, especially American and Asian authors, and for us.5,10,18,20,24,31,33 This position allows us to more easily address posterior right lobe lesions and perform a higher percentage of hepatic resections and hemi-hepatectomies. Our unit performed this resection in 16% of cases. The use of the hand reproduces the advantages of open surgery, including liver mobilisation, vascular pedicle control and compression, for some American20,24,31,33 and Japanese authors.38,39

The conversion of TLS to laparotomy oscillates between 0% and 20%.10,16–18,20–38 Our conversion rate is 2.3%, and this rate is related to the approach employed. Therefore, TLS became laparotomy in 3 of the 28 cases, and there was no conversion to ALS. An alternative to conversion to laparotomy from TLS is conversion to ALS, which is a manoeuvre that we and some other authors (0.3% conversion)20,41,42 have used.

The margin of invasion in malignant tumours is a cause for conversion.24,26,30,33,40 The margin with TLS, is accounted for by the performing of repeated scans,1,6,16,17,26,28 and the margin in ALS is accounted for by using palpation and ultrasound examination.5,8,10,20,24,41 Some authors have used radiofrequency ablation of the surgical resection bed when the margin is invaded to prevent conversion,24,41,42 and we employed this approach in 3 of our patients. Adhesions in patients with CLM is another cause of conversion,30,41,42 which occurred in 2 of our cases who also exhibited associated bowel lesions. The most frequent cause for conversion is haemorrhage,1,10,16,17,19,30,36,47 which can occur during the sectioning of the parenchyma or the dissection of the portal vessels, inferior vena cava (IVC) and hepatic segment veins. Manual compression is lost with TLS and requires the bleeding to be controlled mainly with the Pringle manoeuvre. Direct compression in ALS reduces blood loss and provides greater security against possible vascular lesions. Vascular injury is difficult to control, and it often requires conversion. However, some surgeons have sutured lesions of the IVC and hepatic segment veins.6 We control haemorrhage in ALS of IVC lesions, injuries to the right hepatic artery, a portal vein injury and a torn right middle hepatic segment vein by laparoscopic suturing. We suggest that the above techniques and left lateral segmentectomy can be performed safely without vascular occlusion, but the Pringle manoeuvre provides greater security for right posterior segments.

Vascular control of the hepatic segment veins is a complex manoeuvre. Middle and left vascular pedicle dissection can be performed more easily in left hepatectomy because of the space that exists with the IVC, which allows vascular staple transection. We performed this manoeuvre in 5 of the 6 patients. We have performed the control of the right hepatic segment veins, which is a very complicated manoeuvre,6 on 4 occasions.

In conclusion, LLR, either by TLS or ALS, shares all the advantages of minimally invasive surgery (e.g., better and faster postoperative recovery, better cosmesis and less postoperative analgesic requirements) with rates of complications and survival in malignant tumours that are similar to the results reported for open surgery.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Robles Campos R, Marín Hernández C, Lopez-Conesa A, Olivares Ripoll V, Paredes Quiles M, Parrilla Paricio P. Resección hepática por laparoscopia: lecciones aprendidas tras 132 resecciones. Cir Esp. 2013;91:524–533.