One of the most common surgeries performed today in general surgery units is thyroidectomy, which provides good results with low associated morbidity and mortality. The incidence of complications varies depending on the experience of the surgeon, and a perforated trachea is a very uncommon complication.

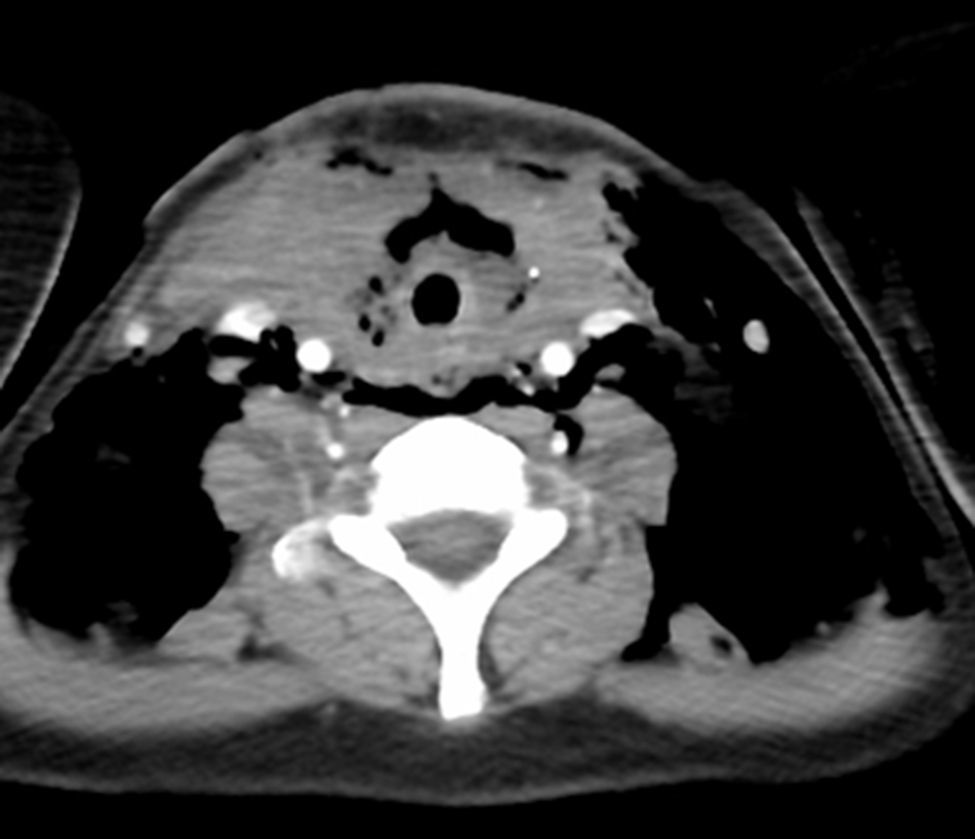

We present the case of a 46-year-old woman who was referred to us for surgical treatment due to Graves-Basedow disease, with grade 3 goitre and ophthalmopathy. Total thyroidectomy was performed with the identification of the parathyroid glands and both recurrent laryngeal nerves. There were no incidences during surgery, and immediate patient progress was satisfactory. Nine days later, the patient came to the emergency department due to progressive facial and neck swelling and a feeling of dyspnoea brought on by a sudden coughing episode. Upon examination, we observed subcutaneous facial, cervical and left thoracic emphysema, with normal lung auscultation (Fig. 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed cervical emphysema (Fig. 2). The surgical wound was opened, which revealed the discharge of purulent material and air that coincided with respiratory movements and cough. With the diagnosis of a tracheal fistula, laryngoscopy confirmed the presence of a small orifice in the anterior side of the trachea at the union of the cricoid cartilage. The patient was hospitalised and treated with conservative antibiotic treatment (piperacillin-tazobactam), low doses of corticosteroids and daily dressing changes. The patient had a favourable progress and was discharged 8 days later and after closure of the tracheal fistula and deferred wound closure.

Iatrogenic tracheal rupture is very uncommon and has been more commonly described as a complication of external radiotherapy, or rather after airway manipulation (orotracheal intubation, bronchoscopy) or cervical and mediastinal surgery.1,2

Nonetheless, tracheal perforation associated with thyroidectomy in particular is extremely rare. In one study, Gosnell et al. identified an incidence of tracheal perforation of 0.06%. Risk factors for tracheal injury are female sex, thyrotoxic goitre, prolonged intubation with a high-pressure endotracheal balloon, use of diathermia (especially with heavy bleeding) and uncontrolled persistent cough in the postoperative period.3,4 Most of these risk factors were present in our patient.

Tracheal injury during thyroidectomy has also been reported in case series, and 2 clearly differentiated scenarios are defined according to the identification of the lesion: (1) the first case is when the lesion is identified during the surgical procedure and is immediately repaired with absorbable sutures; and (2) the second scenario is extremely rare and happens when the injury is not detected by the surgeon during the initial procedure and is discovered after several days, typically with cervical and facial swelling, hoarseness, retrosternal pain and dyspnoea, coinciding with a vigorous coughing episode.1,4

Among the possible causes of this type of lesions, and particularly in our case, the main aetiological agent that has been contemplated is the effect of electro-coagulation, which, although very useful for the control of bleeding, has the potential risk for damaging surrounding structures by lateral heat dispersion. It has also been suggested that tracheomalacia subsequent to tracheal compression by a large goitre over an extended period of time may be another possible cause or predisposing factor for deferred tracheal perforation.5,6

The diagnosis is clinical and based on details of the medical history, a high degree of suspicion and subcutaneous emphysema on palpation. This can be confirmed with flexible or rigid bronchoscopy to locate the tracheal rupture; normal bronchoscopy results, however, do not rule out the diagnosis. A CT scan is useful to dismiss other causes of subcutaneous emphysema, such as oesophageal perforation or pneumothorax.1,4

The recommended treatment varies depending on the cause and the patient's condition. Patients without respiratory distress, with symptoms in resolution and no evidence of infection can be managed conservatively with intravenous antibiotic coverage. In the remainder, surgical treatment should be done without delay, and control of the airway should be a priority. The team should be prepared to perform an emergency tracheostomy, if necessary, although a rapid sequence of anaesthesia induction and orotracheal intubation under optical control with the placement of the endotracheal balloon distal to the injury site is normally sufficient to control the airway. In this type of intubation, positive pressure should be avoided, which can worsen subcutaneous emphysema and lead to respiratory distress. As for the surgical intervention, primary repair is indicated with absorbable sutures over the viable tracheal edges, reinforced with a muscle flap.7 There are also descriptions of the use of patches with a combination of human fibrinogen and human thrombin (TachoSil®) to protect the sutures.1

In our case, given the haemodynamic and respiratory stability of our patient, we decided to opt for a conservative approach. The patient continues to be seen in the surgical outpatient consultation with no further complications to date.

Please cite this article as: González-Sánchez-Migallón E, Guillén-Paredes P, Flores-Pastor B, Miguel-Perelló J, Aguayo-Albasini JL. Perforación traqueal diferida tras tiroidectomía total. Manejo conservador. Cir Esp. 2016;94:50–52.