Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that can affect any segment of the digestive tract from the mouth to the anus. While painless microperforations that cause fistulae are a common complication that can affect 33% of patients after 10 years of illness,1 acute perforation is fortunately a rare presentation, the etiology of which has not been well established. The inflammation and thickening of the intestinal wall in patients with CD could increase the susceptibility to mild external trauma and, therefore, the risk of perforation with a lower intensity of trauma. We present 2 patients with CD and colonic perforation after minor blunt abdominal trauma (MBAT).

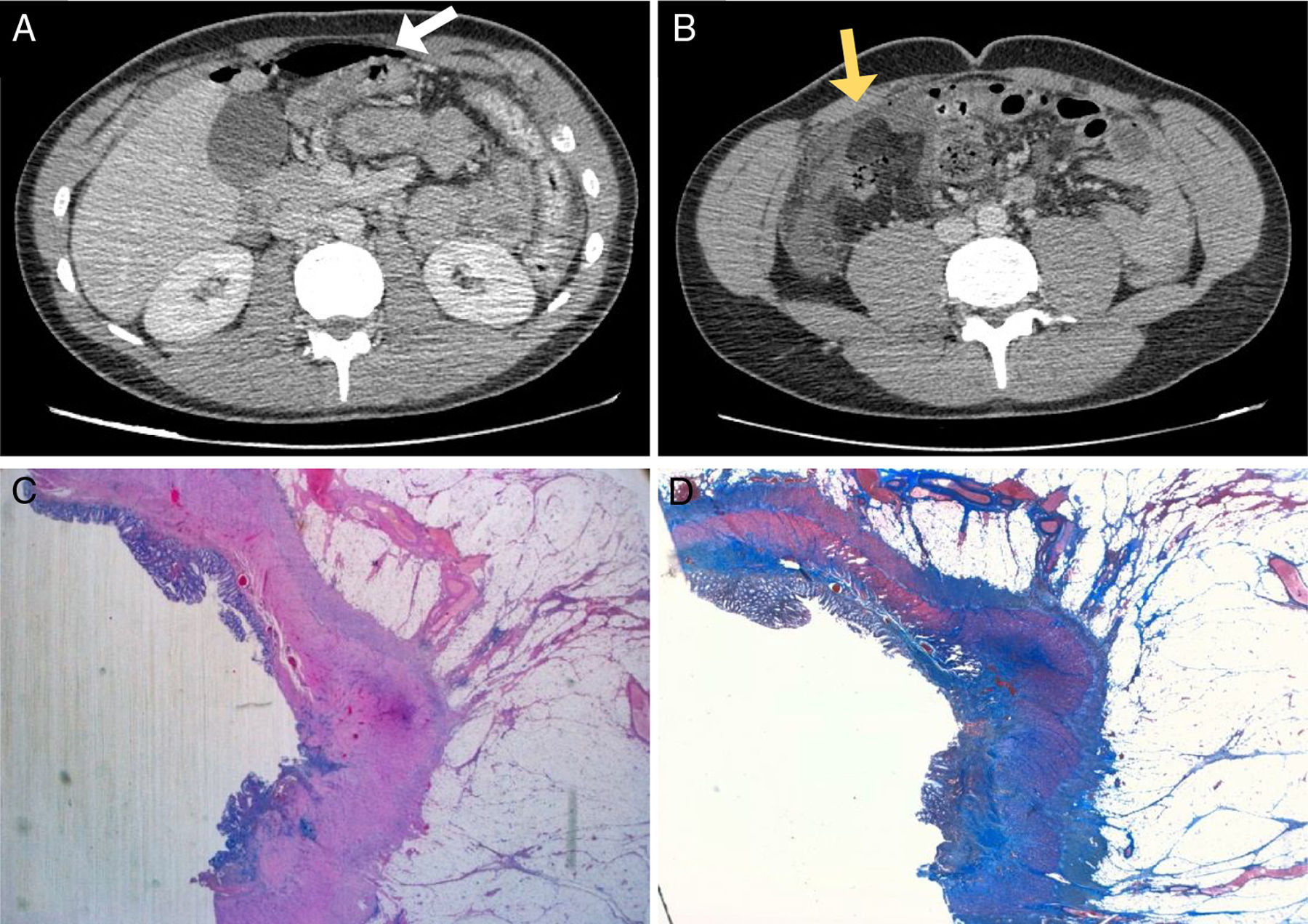

The first patient was a 20-year-old male recently diagnosed with CD of ileocecal and ascending colon involvement, who was receiving treatment with methotrexate and adalimumab. He came to the emergency room for abdominal pain after falling while practicing football and having been hit with the ball in the abdominal region. On physical examination, there were signs of peritoneal irritation; given his hemodynamic stability, a computed tomography (CT) scan was done, which demonstrated pneumoperitoneum, abundant free fluid, and wall thickening of the ascending colon and ileocecal region (Fig. 1A and B). Given these findings, urgent laparotomy was indicated, showing evidence of diffuse fecaloid peritonitis secondary to a 2cm perforation at the hepatic angle of the colon over an area with macroscopic signs of involvement due to CD. Right hemicolectomy was performed. The patient presented postoperative complications (including surgical wound infection and intra-abdominal collection) and was discharged on the 30th postoperative day. The pathological examination of the specimen found evidence of changes compatible with Crohn-type inflammatory bowel disease, with margins free of involvement and perforation with acute peritonitis (Fig. 1C and D).

(A) Axial view on CT showing hydropneumoperitoneum (white arrow); (B) axial view on CT showing intestinal wall thickening in the ileocecal region with evidence of extraluminal bubbles (yellow arrow); (C) histopathological study (panoramic) demonstrating an area of ulceration and chronic inflammatory infiltrate, accompanied by fibrous tracts that distort and fade the muscle layer; (D) histopathological study (Masson's trichrome stain) showing wall thickening due to fibrosis with transmural involvement.

The second patient was a 39-year-old male with CD for 20 years being treated with azathioprine. He came to the emergency department for abdominal pain and hematochezia that had started 48h before, after a MBAT while practicing martial arts. On examination, he presented a painful abdomen with peritoneal irritation. X-ray and ultrasound initially showed no significant findings. However, given the persistent symptoms, an abdominal CT scan was ordered, which revealed pneumoperitoneum adjacent to the mid-transverse colon and alterations of the local fat. Given the findings, urgent laparotomy was indicated, and a covered perforation was found in the transverse colon. An extended right hemicolectomy with primary anastomosis was performed. The patient recovered with no postoperative incidents and was discharged from hospital on the 8th postoperative day. The pathology study confirmed a perforation in the intestinal wall with changes compatible with CD and the presence of inflammatory activity.

Although the etiopathogenesis of CD is not well established, the most accepted theory is an immune dysregulation in genetically susceptible patients against the resident bacterial flora and other intraluminal antigens, which would result in an inflammation of the intestinal wall. Up to 59% of patients have ileocolic involvement, and 22% have colon involvement alone.1 According to the most recent studies, up to 6.5% of patients with CD will experience intestinal perforation at the onset or after the diagnosis of their baseline disease.2 The factors related to the development of free perforations are not well known, although some authors have suggested the presence of intestinal stenoses, evolution of the disease for more than 30 years2 or the use of anti-TNF alpha (infliximab, adalimumab),3 which is the case of one of our patients. Intestinal perforation after blunt abdominal trauma occurs in 1.3% of patients,4 and the incidence is even lower in the case of MBAT, suggesting a predisposing underlying factor.

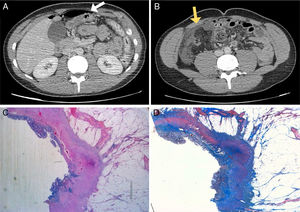

The patients that we present had experienced colonic perforation after very low-intensity trauma, located in areas with the presence of inflammatory activity typical of CD. The transmural inflammation of the wall would constitute a predisposing factor, making the intestine more susceptible to perforation in situations of MBAT compared to patients without CD, in whom the MBAT would have probably had no major consequences. Only 6 cases are found in the literature5–10 of intestinal perforation after MBAT in patients with CD (Table 1); similar to our patients, most of these occurred in young male subjects with ileocolic/colic involvement while participating in sports activities. Therefore, in patients with these characteristics, caution is recommended when practicing sports, especially when under chemotherapy or biological treatment. In most of the published cases, the low intensity of the trauma and its insidious presentation caused an undervaluation of the magnitude of the lesions that presented and, consequently, a delay in the diagnosis (ranging from 5h to 2 days). In these patients, a high diagnostic suspicion is therefore essential. The treatment is eminently surgical, and the area of the perforation must be resected to obtain healthy margins that are free of disease. The indication for the primary anastomosis is influenced by the clinical characteristics and hemodynamic stability of the patient, as well as any intraoperative findings.

Cases Published in the Literature of Intestinal Perforation After Mild Abdominal Trauma in Patients With Crohn's Disease.

| Reference | No. | Age | Sex (M/F) | Anti-TNF | Mechanism of Trauma | Diagnostic Method | Surgical Findings | Surgical Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson and Baker, 19905 | 1 | 26 | M | No | Basketball | CT | Perforation in sigmoid colon | Sigmoidectomy+end colostomy |

| Gur et al., 19956 | 1 | 28 | F | No | Traffic | Symptoms | Perforation in transverse colon | Segmental resection+colostomy |

| Bunni et al., 20087 | 1 | 21 | M | – | Football | CT | Perforation in ascending colon | Right hemicolectomy+primary anastomosis |

| Wagner et al., 20128 | 1 | 22 | M | No | Traffic | CT | Perforation in ileum | Ileocecal resection+primary anastomosis |

| Maconi et al., 20139 | 1 | 46 | M | Yes | Skiing | CT | Perforation distal ileum; ileosigmoid fistula | Ileocecal resection Sigmoidectomy+primary anastomosis |

| Onwubiko et al., 201510 | 1 | 13 | F | No | Water sports | CT | Perforation in distal ileum | Ileocecal resection+primary anastomosis |

| Pérez Jiménez et al., 2019 | 2 | 20 | M | Yes | Football | CT | Perforation in ascending colon | Right hemicolectomy+primary anastomosis |

| 39 | M | No | Martial arts | CT | Perforation in transverse colon | Extended right hemicolectomy+primary anastomosis |

CT: computed tomography; F: female; M: male; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

The authors of this case report have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Jiménez A, de la Serna S, Palomar J, Sanz-Ortega G, Torres AJ. Traumatismo abdominal leve en pacientes con enfermedad de Crohn: ¿mayor susceptibilidad a la perforación de colon? Cir Esp. 2020;98:55–57.