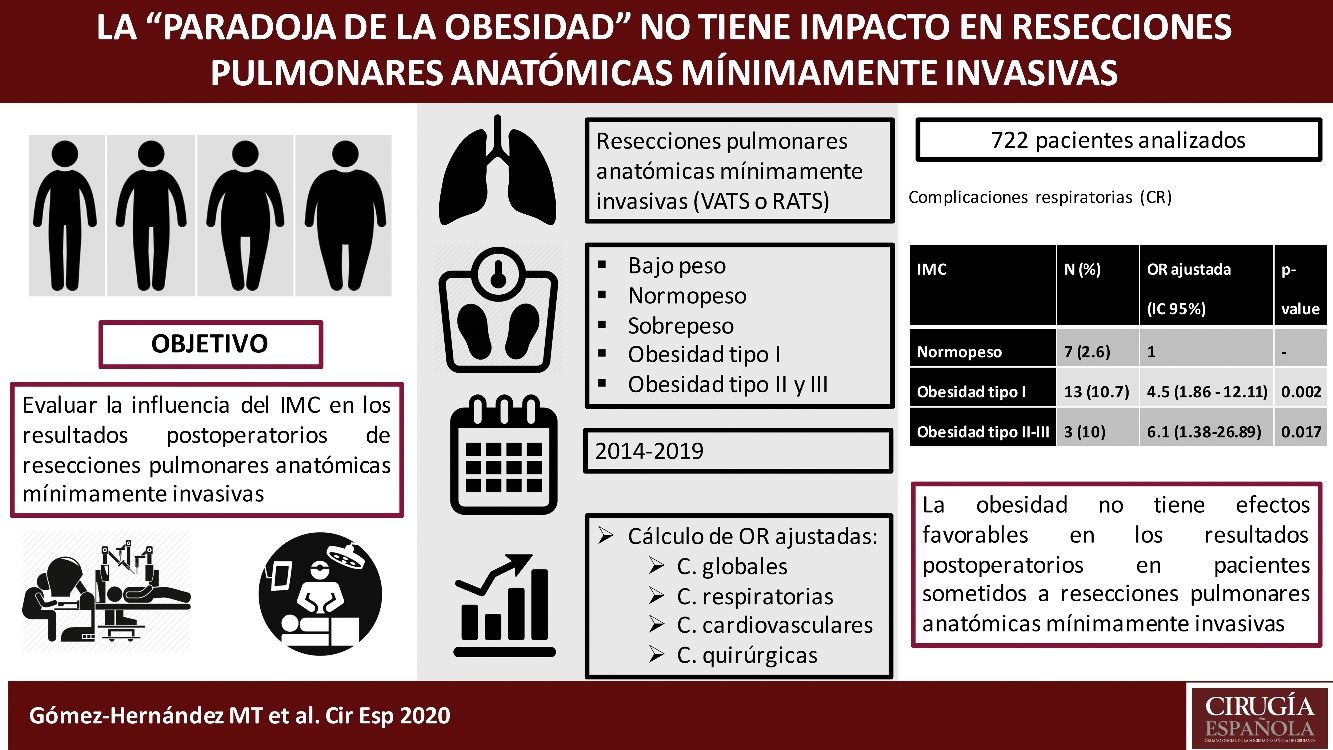

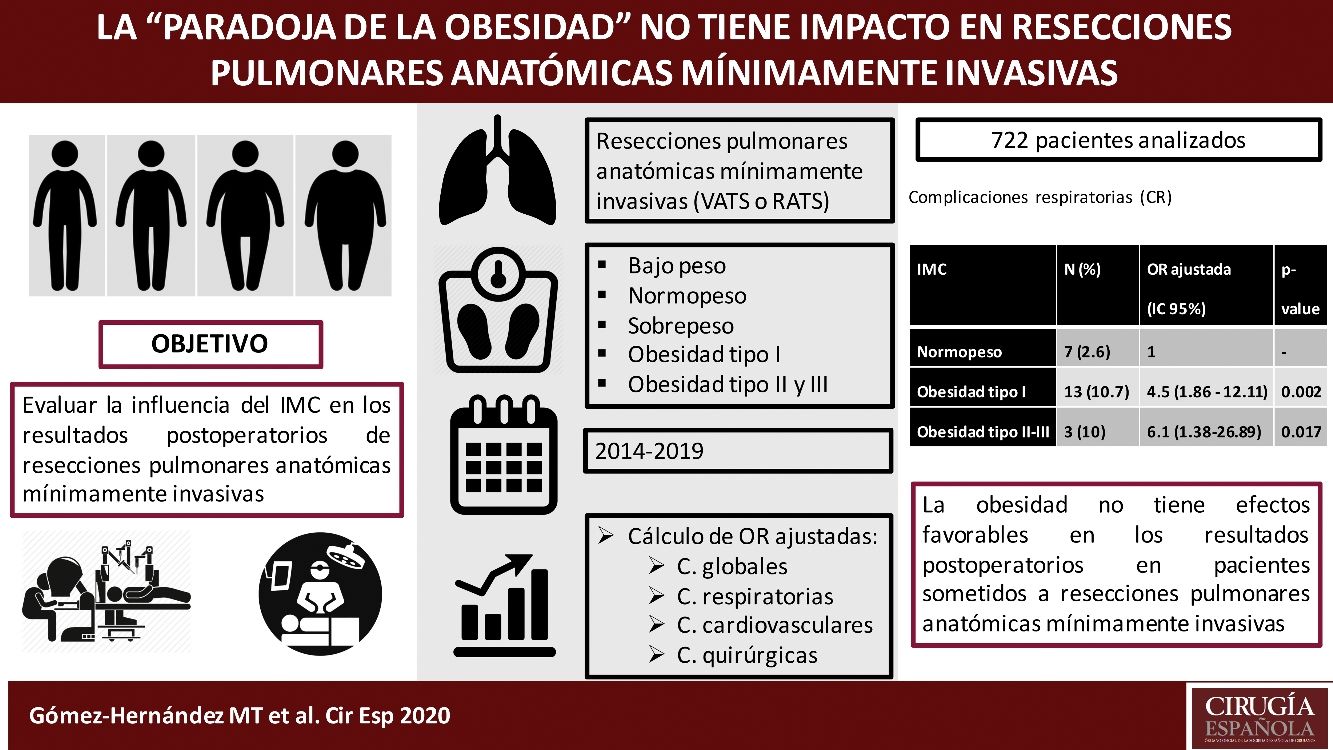

The paradoxical benefit of obesity, the ‘obesity paradox’, has been analyzed in lung surgical populations with contradictory results. Our goal was assessing the relationship of body mass index (BMI) to acute outcomes after minimally invasive major pulmonary resections.

MethodsRetrospective review of consecutive patients who underwent pulmonary anatomical resection through a minimally invasive approach for the period 2014–2019. Patients were grouped as underweight, normal, overweight and obese type I, II and III. Adjusted odds ratios regarding postoperative complications (overall, respiratory, cardiovascular and surgical morbidity) were produced with their exact 95% confidence intervals. All tests were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

ResultsAmong 722 patients included in the study, 37.7% had a normal BMI and 61.8% were overweight or obese patients. When compared with that of normal BMI patients, adjusted pulmonary complications were significantly higher in obese type I patients (2.6% vs 10.6%, OR: 4.53 [95%CI: 1.86–12.11]) and obese type II–III (2.6% vs 10%, OR: 6.09 [95%CI: 1.38–26.89]). No significant differences were found regarding overall, cardiovascular or surgical complications among groups.

ConclusionsObesity has not favourable effects on early outcomes in patients undergoing minimally invasive anatomical lung resections, since the risk of respiratory complications in patients with BMI≥30kg/m2 and BMI≥35kg/m2 is 4.5 and 6 times higher than that of patients with normal BMI.

El beneficio paradójico de la obesidad, la «paradoja de la obesidad», ha sido analizado en distintas series de cirugía de resección pulmonar con conclusiones contradictorias. El objetivo del estudio es evaluar la influencia del índice de masa corporal (IMC) en los resultados postoperatorios de resecciones pulmonares anatómicas por vía mínimamente invasiva.

MétodosRevisión retrospectiva de pacientes consecutivos sometidos a resección pulmonar anatómica a través de un abordaje mínimamente invasivo durante el período comprendido entre 2014 y 2019. Los pacientes se agruparon en: bajo peso, normopeso, sobrepeso y obesidad tipo I, II y III. Se calcularon las odds ratio ajustadas con respecto a las distintas complicaciones (globales, respiratorias, cardiovasculares y quirúrgicas) con sus intervalos de confianza al 95% (IC 95%). Todas las pruebas se consideraron estadísticamente significativas con p<0,05.

ResultadosEntre 722 pacientes incluidos en el estudio, el 37,7% tenían un IMC normal y el 61,8% eran pacientes con sobrepeso u obesidad. En comparación con los pacientes con IMC normal, las complicaciones pulmonares ajustadas fueron significativamente mayores en los pacientes obesos tipo I (2,6 vs. 10,6%; OR: 4,53 [IC 95%: 1,72-11,92]) y obesos tipo II-III (2,6 vs. 10%; OR: 6,09 [IC 95%: 1,38-26,89]). No se encontraron diferencias significativas con respecto a las complicaciones globales, cardiovasculares o quirúrgicas entre los distintos grupos.

ConclusionesLa obesidad no tiene efectos favorables en los resultados postoperatorios en pacientes sometidos a resecciones pulmonares anatómicas mínimamente invasivas. El riesgo de complicaciones respiratorias en pacientes con IMC≥30kg/m2 e IMC≥35kg/m2 es 4,5 y 6 veces mayor que el de pacientes con IMC normal.

Obesity has been classically considered a patient related factor that could increase the perioperative risk of surgical patients1 owing to associated comorbidities such as hypertension, coronary artery disease and diabetes, and physiological impairment of ventilation. However, in recent years, this traditional view has been strongly challenged by reports examining body mass index (BMI) that demonstrate an inverse relationship with morbidity and mortality in the patient. This phenomenon is known as the ‘obesity paradox’, which refers to a better prognosis in obese patients compared to normal/underweight patients.2 The paradoxical benefit of obesity has been mainly described in critical care, where critically ill obese patients have shown improved critical care-related outcomes (“obesity-critical care paradox”),3 but it has also found in a wide range of cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases as well as in the surgical population. Recent reports evaluating the influence of BMI on acute outcomes of major lung resection have shown mixed results. Some studies substantiated the increased risk,4,5 while others failed to demonstrate it.6,7 More recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis carried out by Li et al.8 concluded that obesity has favourable effects on in-hospital outcomes and long-term survival of surgical patients with lung cancer and mainly operated through an open approach. According to the authors the ‘obesity paradox’ does have the potential to exist in lung cancer surgery. Because of contradictions in the literature, the effects of BMI on surgical outcomes of patients undergoing anatomical lung resection remain controversial and no consensus has been reached on the prognostic value of BMI in lung resection surgery.

On the other hand, minimally invasive surgery has become the standard approach for lung resections regarding its benefits over conventional thoracotomy in short- and long-term outcomes.9,10 According to a prospective multicentre cohort study of the Spanish video-assisted thoracic surgery group (GEVATS), more than 50% of anatomical lung resections performed in Spain between 2016 and 2018 were performed through a video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) approach11 and this percentage surpasses 40% according to the European database annual report.12

To date, no studies have evaluated the relationship of BMI and postoperative outcomes after minimally invasive anatomical lung resections. The purpose of this observational study was to clarify the impact of BMI on the postoperative outcomes of patients after minimally invasive anatomical lung resection.

MethodsPatient populationRetrospective review of our institutional database of consecutive patients undergoing pulmonary anatomical resection for any cause through a minimally invasive approach in our department along the period 2014–2019. Inclusion criteria were patients at least 18 years old who underwent elective anatomical lung resection (anatomical segmentectomy, lobectomy or bilobectomy or pneumonectomy) by VATS or robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS). Emergency procedures were excluded.

Patient selection criteria were homogeneous all over the recruitment period and were based on the physiologic evaluation recommended by the evidence-based clinical practice guideline published in 2013.13

Based on tumour features, minimally invasive approach was the recommended approach for all cases except when an extended resection (associated to chest wall, atrial, vena cava, diaphragm or vertebral resection, sleeve resections, pleuropneumonectomy, or intrapericardial pneumonectomy) was potentially needed. In these cases, postero-lateral or muscle-sparing thoracotomy was performed.

All procedures were performed by a team of five board certified thoracic surgeons who performed at least 30 thoracoscopic lobectomies annually.

From this population, patients were divided into six cohorts based on their body mass index (BMI): underweight (BMI<18.5kg/m2) normal (BMI≥18.5 and <25kg/m2), overweight (BMI≥25 and <30kg/m2), obese type I (BMI≥30kg/m2 and <35kg/m2), obese type II (BMI≥35kg/m2 and <40kg/m2) and obese type III (BMI≥40kg/m2).

Outcome definitionThe primary endpoint was operative overall morbidity defined as any adverse event occurred within 30 days after the operation, or later if the patient was still in the hospital. Secondary endpoints were pulmonary, cardiovascular, and surgical complications. Pulmonary complications included atelectasis requiring bronchial aspiration by bronchoscopy, confirmed or suspected pneumonia, respiratory failure requiring invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation. Cardiovascular complications included deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, atrial fibrillation, stroke, acute coronary events, and acute heart failure. Surgical complications included vocal cord palsy, bronchial fistula, prolonged (>7 days) air leaks, haemothorax, chylothorax, empyema and wound abscess.

Statistical analysisDemographic, physiological, operative and outcomes variables were collected.

Univariate analysis for adverse events (overall, pulmonary, cardiovascular and surgical) was performed for the following variables: BMI, age, sex, smoking status, cardiac comorbidity, predicted postoperative forced expiratory volume in the first second (ppo VEF1) and postoperative diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (ppoDLCO) -both values according to the number of functional pulmonary segments to be resected-, type of resection (anatomical segmentectomy, lobectomy, bilobectomy and pneumonectomy) and diagnosis (malignant neoplastic tumour including primary neoplasm of the lung and metastases other than lung, and benign tumours). Influence of continuous variables with normal distribution on outcomes was tested using the unpaired Student's t-test, whereas those without normal distribution were tested using the Mann–Whitney U test and ANOVA. Categorical variables were tested by the chi-squared test or the Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Significant variables on univariate analysis were used to fit a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Adjusted odds ratios regarding postoperative complications were produced with their exact 95% confidence intervals. For the multivariate logistic regression analysis, BMI was divided into five categories, so that patients with obesity type II and III were grouped in the same category.

Subsequently, a subgroup analysis of patients with BMI≥30kg/m2 was conducted. This group was divided according to the association or not of comorbidities related to metabolic syndrome (high triglyceride level, low HDL cholesterol level, high blood pressure and a high fasting blood sugar). The influence of metabolic syndrome related comorbidities on postoperative complications after minimally invasive anatomical lung resection in patients with BMI≥30kg/m2 was analyzed by the chi-squared test of the Fisher's exact test.

All tests were two-sided, with statistical significance set at a p value of less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were undertaken with SPSS software, version 26 (IBM Corp., Chicago, Illinois, 2019).

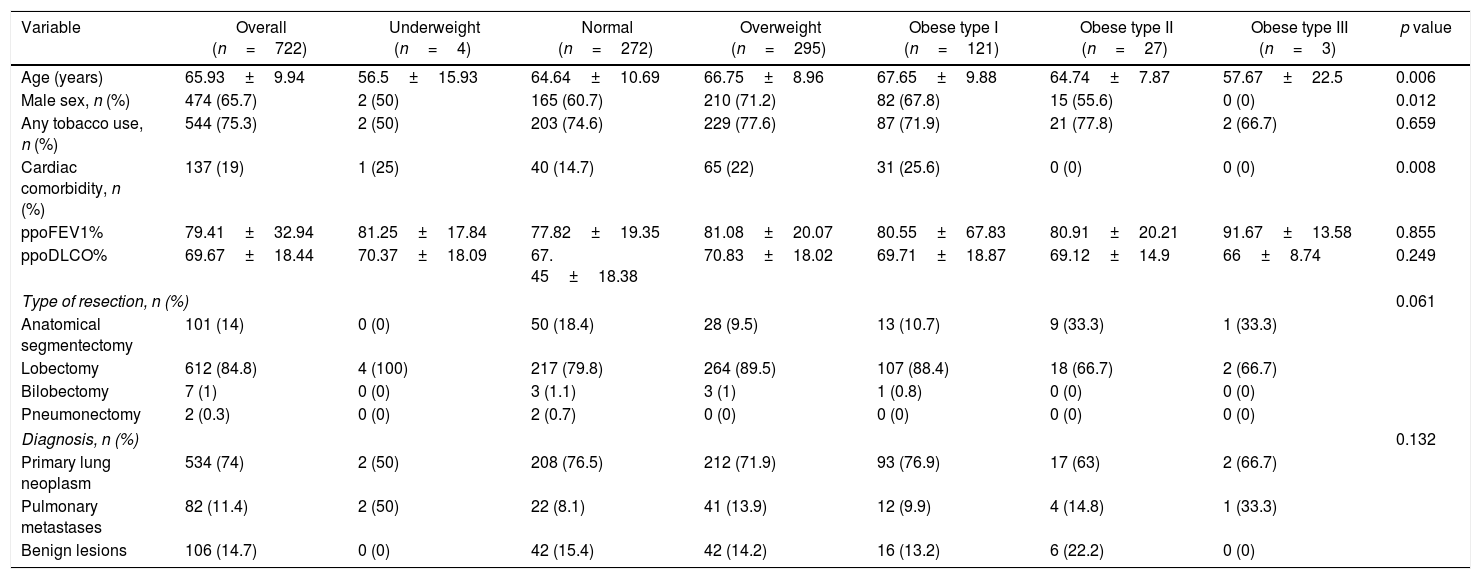

ResultsAmong 722 patients included in the study, only 4 patients had a BMI<18.5kg/m2, 37.7% had a normal BMI, 40.9% were overweight patients, 16.8% were obese type I, 3.7% had obesity type II and only three patients were obese type III. The characteristics of the patients included in the analysis are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients included in the analysis.

| Variable | Overall (n=722) | Underweight (n=4) | Normal (n=272) | Overweight (n=295) | Obese type I (n=121) | Obese type II (n=27) | Obese type III (n=3) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.93±9.94 | 56.5±15.93 | 64.64±10.69 | 66.75±8.96 | 67.65±9.88 | 64.74±7.87 | 57.67±22.5 | 0.006 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 474 (65.7) | 2 (50) | 165 (60.7) | 210 (71.2) | 82 (67.8) | 15 (55.6) | 0 (0) | 0.012 |

| Any tobacco use, n (%) | 544 (75.3) | 2 (50) | 203 (74.6) | 229 (77.6) | 87 (71.9) | 21 (77.8) | 2 (66.7) | 0.659 |

| Cardiac comorbidity, n (%) | 137 (19) | 1 (25) | 40 (14.7) | 65 (22) | 31 (25.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.008 |

| ppoFEV1% | 79.41±32.94 | 81.25±17.84 | 77.82±19.35 | 81.08±20.07 | 80.55±67.83 | 80.91±20.21 | 91.67±13.58 | 0.855 |

| ppoDLCO% | 69.67±18.44 | 70.37±18.09 | 67. 45±18.38 | 70.83±18.02 | 69.71±18.87 | 69.12±14.9 | 66±8.74 | 0.249 |

| Type of resection, n (%) | 0.061 | |||||||

| Anatomical segmentectomy | 101 (14) | 0 (0) | 50 (18.4) | 28 (9.5) | 13 (10.7) | 9 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Lobectomy | 612 (84.8) | 4 (100) | 217 (79.8) | 264 (89.5) | 107 (88.4) | 18 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Bilobectomy | 7 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pneumonectomy | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.132 | |||||||

| Primary lung neoplasm | 534 (74) | 2 (50) | 208 (76.5) | 212 (71.9) | 93 (76.9) | 17 (63) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Pulmonary metastases | 82 (11.4) | 2 (50) | 22 (8.1) | 41 (13.9) | 12 (9.9) | 4 (14.8) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Benign lesions | 106 (14.7) | 0 (0) | 42 (15.4) | 42 (14.2) | 16 (13.2) | 6 (22.2) | 0 (0) | |

Results are expressed as means (standard deviations) unless otherwise specified.

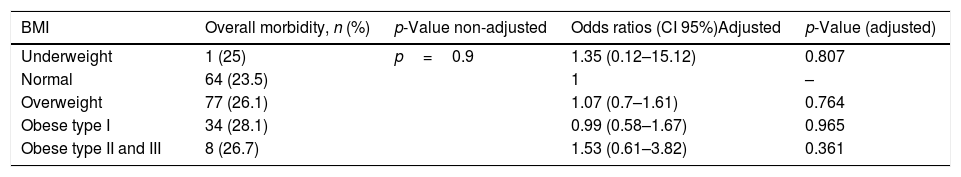

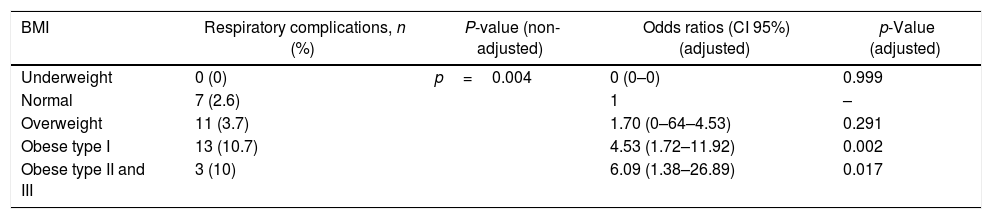

Mortality rate was 1/722 (a patient in the overweight BMI subset). The overall postoperative complication rate was 25.5%. Surgical complications appeared in 15.8% of patients. Those were the most common, followed by respiratory (4.7%) and cardiovascular (4.5%) complications. The statistical relationship between overall, respiratory, cardiovascular, surgical complications and BMI patient's category is showed in Tables 2–5, respectively.

Association of BMI and overall morbidity after minimally invasive (VATS/RATS) major lung resection.

| BMI | Overall morbidity, n (%) | p-Value non-adjusted | Odds ratios (CI 95%)Adjusted | p-Value (adjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | 1 (25) | p=0.9 | 1.35 (0.12–15.12) | 0.807 |

| Normal | 64 (23.5) | 1 | – | |

| Overweight | 77 (26.1) | 1.07 (0.7–1.61) | 0.764 | |

| Obese type I | 34 (28.1) | 0.99 (0.58–1.67) | 0.965 | |

| Obese type II and III | 8 (26.7) | 1.53 (0.61–3.82) | 0.361 |

BMI: body mass index. CI: confidence interval.

Adjusted analysis for overall morbidity. Co-variables: age, male sex, smoking status, cardiac comorbidity, ppoFEV1% and ppoDLCO%.

Association of BMI and respiratory complications after minimally invasive (VATS/RATS) major lung resection.

| BMI | Respiratory complications, n (%) | P-value (non-adjusted) | Odds ratios (CI 95%) (adjusted) | p-Value (adjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | 0 (0) | p=0.004 | 0 (0–0) | 0.999 |

| Normal | 7 (2.6) | 1 | – | |

| Overweight | 11 (3.7) | 1.70 (0–64–4.53) | 0.291 | |

| Obese type I | 13 (10.7) | 4.53 (1.72–11.92) | 0.002 | |

| Obese type II and III | 3 (10) | 6.09 (1.38–26.89) | 0.017 |

BMI: body mass index. CI: confidence interval.

Adjusted analysis for respiratory complications. Co-variables: ppoFEV1%.

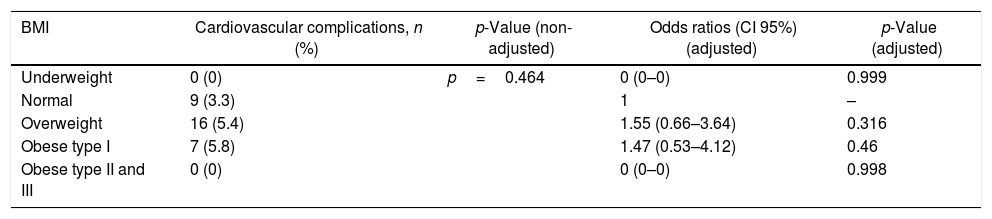

Association of BMI and cardiovascular complications after minimally invasive (VATS/RATS) major lung resection.

| BMI | Cardiovascular complications, n (%) | p-Value (non-adjusted) | Odds ratios (CI 95%) (adjusted) | p-Value (adjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | 0 (0) | p=0.464 | 0 (0–0) | 0.999 |

| Normal | 9 (3.3) | 1 | – | |

| Overweight | 16 (5.4) | 1.55 (0.66–3.64) | 0.316 | |

| Obese type I | 7 (5.8) | 1.47 (0.53–4.12) | 0.46 | |

| Obese type II and III | 0 (0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.998 |

BMI: body mass index. CI: confidence interval.

Adjusted analysis for cardiovascular complications. Co-variables: age and ppoFEV1%.

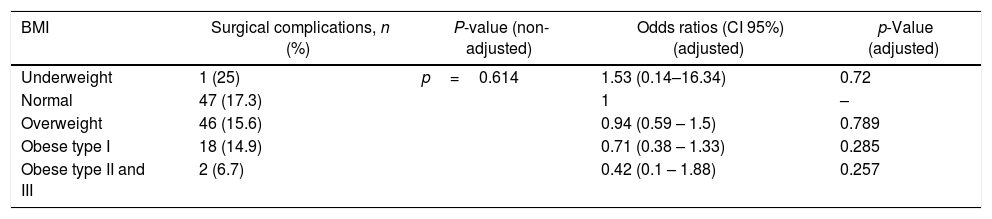

Association of BMI and surgical complications after minimally invasive (VATS/RATS) major lung resection.

| BMI | Surgical complications, n (%) | P-value (non-adjusted) | Odds ratios (CI 95%) (adjusted) | p-Value (adjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | 1 (25) | p=0.614 | 1.53 (0.14–16.34) | 0.72 |

| Normal | 47 (17.3) | 1 | – | |

| Overweight | 46 (15.6) | 0.94 (0.59 – 1.5) | 0.789 | |

| Obese type I | 18 (14.9) | 0.71 (0.38 – 1.33) | 0.285 | |

| Obese type II and III | 2 (6.7) | 0.42 (0.1 – 1.88) | 0.257 |

BMI: body mass index. CI: confidence interval.

Adjusted analysis for surgical complications. Co-variables: cardiac comorbidity, ppoFEV1% and ppoDLCO%.

When compared with normal BMI patients, obese type I and type II-III patients experienced significantly more pulmonary complications (the risk was 4.5-fold higher for BMI≥30kg/m2 and 6-fold higher for BMI≥35kg/m2). Overall morbidity rate was similar in all groups, but slightly higher for BMI≥35kg/m2. Overweight and obese type I patients had more cardiovascular complications, but this finding did not reach statistical significance. Instead, overweight obese type I and type II-III patients underwent less surgical complications, although the difference was not statistically significant.

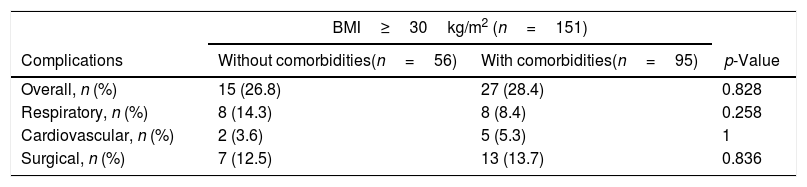

No differences were found regarding the influence of metabolic syndrome related comorbidities in patients with BMI≥30kg/m2 (Table 6).

Influence of metabolic syndrome related comorbidities on postoperative complications after minimally invasive (VATS/RATS) major lung resection in patients with BMI≥30kg/m2.

| BMI≥30kg/m2 (n=151) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | Without comorbidities(n=56) | With comorbidities(n=95) | p-Value |

| Overall, n (%) | 15 (26.8) | 27 (28.4) | 0.828 |

| Respiratory, n (%) | 8 (14.3) | 8 (8.4) | 0.258 |

| Cardiovascular, n (%) | 2 (3.6) | 5 (5.3) | 1 |

| Surgical, n (%) | 7 (12.5) | 13 (13.7) | 0.836 |

Obesity affects 10–30% of adults in European countries and represents the greatest pandemic of the twenty-first century in developed countries.14 A recent report from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database indicated that nearly 26% of patients undergoing lung resection were obese.15 According to our results, a high percent (61.6%) of patients undergoing minimally invasive major lung resection were over weighted or obese ones.

The “obesity paradox” was first described in 1999 among obese patients undergoing hemodialysis.16 Subsequently, in 2002, Gruberg et al.17 published better outcomes in moderately obese patients with coronary heart disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and in 2010, Vemmos et al.18 described the “obesity-stroke paradox” which underlined the idea of obese and overweight patients have significantly better early and long-term survival rates after acute first-ever stroke. There are also several studies that suggest “obesity paradox” among patients undergoing cardiac surgery.19 However, data regarding the relationship between BMI and short-term outcomes of lung resections are contradictory. During the last decade, several studies focused on the impact of BMI in major anatomical resections have been published.4,5,7,14,20–26 However, there is no clear consensus and scanty information about the influence of BMI in minimally invasive pulmonary resections is available due either to, included patients were operated on through an open approach or the surgical approach was not described.

Given that minimally invasive approach has become the standard approach for lung resections, our aim in this study was to evaluate the relationship of BMI, particularly overweight and obese status, in short-term outcomes after minimally invasive major resections.

We explored the interactions of BMI and acute outcomes after minimally invasive major resections using our institutional database. We limited the inclusion period to the last five years to avoid bias regarding selection and perioperative management and we focused in overweight and obese patients. Taking these factors into account, we found an important increase in pulmonary morbidity risk associated with overweight or obese status. Although we found no important increase in perioperative risk in the remaining categories (overall, cardiovascular, and surgical). Our findings are similar to those reported by Petrella et al.4 and Launer et al.5

Our results demonstrated that when compared to that of normal BMI patients, adjusted overall morbidity was slightly higher in overweight and obese type I and type II–III patients (23.5% vs 26.1%, 28.1% and 26.7%, respectively), although differences were not statically significant. These results are similar to those published by others5,6,7,14,22,26 who found that being overweight/obese/very obese did not increase the risk of overall postoperative complications. However, Thomas el at.24 found opposite results in lung cancer patients referred to lobectomy with a significantly lower incidence of overall complications in overweight and obese compared to those of normal BMI cases. Same results were presented by Williams et al.25 who concluded that being underweight or severely overweight is associated with an increased risk of complications, whereas being overweight or moderately obese appears has a protective effect.

Furthermore, being obese in our study carried important increased risks of postoperative pulmonary complications. Moreover, our results showed a lower overall rate of respiratory complications (4.7%) than other similar studies4,24 and similar to those described by Ferguson et al.26 in the last period of their study (2010–2011). The main reason that could explain the difference is that all patients included in our analysis participated in our specific pre- and postoperative chest physiotherapy intensive programme influencing the rate of overall pulmonary morbidity after lobectomy for lung cancer.27 Our findings show that adjusted risk for pulmonary complications was significantly higher in obese type I patients compared to normal BMI patients (10.7% vs 2.6%, OR: 4.53 [95%CI: 1.72–11.92]; p=0.002) and was even higher in patients with BMI≥35kg/m2 (10% vs 2.6%, OR: 6.09 [95%CI: 1.38–26.89]; p=0.017). Similarly, Launer et al.5 found that obese patients (BMI≥30kg/m2) have an increased risk of postoperative pulmonary insufficiency and pneumonia after lobectomy for cancer. Furthermore, by reviewing 154 patients undergoing pneumonectomy, Petrella et al.4 found that obese patients (defined as BMI≥25kg/m2) had a 5-fold increase in respiratory complications.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain pulmonary abnormalities in obese patients: obesity-induced abnormal respiratory system mechanics, impaired central responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia, sleep-disordered breathing and neurohormonal abnormalities such as leptin resistance.28 Moreover, obesity imposes a significant mechanical load leading to mechanical compression of the diaphragm, lungs, and chest cavity, which can lead to restrictive pulmonary damage. Furthermore, fat excess decreases total respiratory system compliance, increases pulmonary resistance, and reduces respiratory muscle strength.29 Conversely, Thomas et al.,24 Willliams et al.25 and Ferguson et al.26 found than being underweight was significantly associated with an increased risk of pulmonary complications (OR: 1.67, OR: 1.41 and OR: 2.48, respectively), meanwhile overweight/obese status could be a protective factor for that kind of complications.

Overweight and obese type I patients had more overall cardiovascular complications, but this finding did not reach statistical significance. Similar results were found by Thomas et al.,24 although they differ to those of Ferguson et al.26 for whom, the risk of cardiovascular postoperative complications was lower in overweight/obese patients. Our findings are supported by the evidence-base thought that increased body mass is a predictor of increased coronary disease risk, independent of cardiovascular risk factors. According to our data, about 62% of obese patients associate some metabolic syndrome related comorbidity, although it seems to have no influence on postoperative outcomes.

Finally, being obese seems to be a protector factor regarding surgical complications since adjusted surgical morbidity was lower in the BMI≥30kg/m2 and BMI≥35kg/m2 groups (OR: 0.71 [95%CI:0.38–1.3]; p=0.285 and OR: 0.42 [95%CI:0.1–1.88; p=0.257, respectively). There is a perceived intraoperative advantage for the surgeon operating on thin patients due to the easily discerned internal anatomy. And there is a greater technical and physical demand engendered by excess mediastinal fat on overweight/obese patients which is associated with increased operating time for major lung resection.30 Despite these two factors, low BMI is associated with increased perioperative risks owing to nutritional depletion, muscle weakness and altered metabolism that affect responses to inflammation and wound-healing processes. So that, attention should be given to specific intraoperative actions to prevent some surgical complications such as prolonged air leaks and bronchial stump fistula in BMI<25kg/m2 patients.

Certain limitations constrain the broad interpretation of the presented data. Firstly, our study is limited by its retrospective nature. Secondly, the number of patients at low extreme (BMI<18.5kg/m2) in our population was very low (n=4), so we focused on comparing normal BMI patients (37.7%) to overweight (40.9%) and obese type I patients (16.8%) and obese type II and III (4.2%). We consider these percentages reflect the distribution of BMI among Spanish population. Finally, BMI may not be the most accurate measurement of nutritional status and nutritional-related perioperative risk. Albumin and other nutritional parameters were not routinely recorded, and no other measures of adiposity or muscle mass were performed. It has been demonstrated that computed tomography quantitative measurement of visceral adiposity and clinical assessment of sarcopenia may identify at-risk populations independently of BMI.31

ConclusionIn summary, we couldn’t find any evidences that the ‘obesity paradox’ happens in minimally invasive major lung resections. Obesity have not favourable effects on early outcomes in patients undergoing minimally invasive anatomical lung resections, since the risk of respiratory complications in patients with BMI≥30kg/m2 and BMI≥35kg/m2 is 4.5 and 6 times higher respectively than that of patients with normal BMI. Efforts should be made to provide aggressive prophylactic respiratory therapies in the perioperative period to these patients.

FundingThis research has not received specific aid from agencies of the public sector, commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest directly or indirectly related to the contents of the manuscript.